Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Ratchaburi

Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Ratchaburi Dragon Jar 4 Ratchaburi CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 9 Amphoe Mueang Ratchaburi 9 Amphoe Pak Tho 16 Amphoe Wat Phleng 16 Amphoe Damnoen Saduak 18 Amphoe Bang Phae 21 Amphoe Ban Pong 22 Amphoe Photharam 25 Amphoe Chom Bueng 30 Amphoe Suan Phueng 33 Amphoe Ban Kha 37 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 38 LOCAL PRODUCTS & SOUVENIRS 39 INTERESTING ACTIVITIS 43 Cruising along King Rama V’s Route 43 Driving Route 43 Homestay 43 SUGGEST TOUR PROGRAMMES 44 TRAVEL TIPS 45 FACILITIES IN RATCHABURI 45 Accommodations 45 Restaurants 50 Local Product & Souvenir Shops 54 Golf Courses 55 USEFUL CALLS 56 Floating Market Ratchaburi Ratchaburi is the land of the Mae Klong Basin Samut Songkhram, Nakhon civilization with the foggy Tanao Si Mountains. Pathom It is one province in the west of central Thailand West borders with Myanmar which is full of various geographical features; for example, the low-lying land along the fertile Mae Klong Basin, fields, and Tanao Si Mountains HOW TO GET THERE: which lie in to east stretching to meet the By Car: Thailand-Myanmar border. - Old route: Take Phetchakasem Road or High- From legend and historical evidence, it is way 4, passing Bang Khae-Om Noi–Om Yai– assumed that Ratchaburi used to be one of the Nakhon Chai Si–Nakhon Pathom–Ratchaburi. civilized kingdoms of Suvarnabhumi in the past, - New route: Take Highway 338, from Bangkok– from the reign of the Great King Asoka of India, Phutthamonthon–Nakhon Chai Si and turn into who announced the Lord Buddha’s teachings Phetchakasem Road near Amphoe Nakhon through this land around 325 B.C. -

World Bank Document

MS& ~C3 E-235 VOL. 20 KINGDOM OF THAILAND PETROLEUM AUTHORITY OF THAILAND Public Disclosure Authorized NA-TURAL GAS PIPELINE PROJECT FROM BANG PAKONG TO WANG NOI EGAT - INVESTMENTPROGRAM SUPPORT PROJECT (WORLDBANK PARTIALCREDIT GUARANTEE) Public Disclosure Authorized DRAFT FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized PREPARED BY TEAM CONSULTING ENGINEERS CO., LTD. FOR BECHTEL INTERNATIONAL, INC. Public Disclosure Authorized JUNE 1994 EZITEAM CONSULTINGENGINEERS CO., LTD. Our Ref: ENV/853/941237 2 June 1994 Mr. Emad M.Khedr Project Engineer 15th Floor, PTT Head Office Building 555 Vibhavadi-RangsitRoad Bangkok 10900, Thailand Dear Sir: Re: EnvironmentalImpact Assessment of Natural Gas Pipeline Project from Bang Pakong to Wans Noi We are pleased to submit herewith 5 copies of the Environmental Impact Assessmentof the Natural Gas Pipeline Project from Bang Pakong to Wang Noi for your considerations. We would like to thank the concerned Bechtel International personnel for their assistances throughout the course of study. Sincerely yours, Amnat Prommasutra Executive Director 51/301-305 Drive-inCenter, Ladprao Road, Soi 130,Bangkapi. Bangkok 10240. Thailand Telex:82855 TRIREXTH. ATTN: TEAM CONSULT.Fax :66 -2-3751070Tel. : 3773480. 3771770.1 'Ulll ?¶a. i LHunh1711n 4l nu nhJf11rnfllfl lusuo"wfl fupiuij iin ....... l2eUwl0t.._,,a,.,._l.~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ ~...... .......... .......... 1: ^ d Id II¶Ut.'1 *'Al lem. LtU TThJwi Id , 1* . ^ t.1 4 - ... ... .. ......................................................................... I... u~~~~~~ i ..................................... 4..~ C f J I Pfl 1 ( ) .L>3?T~I ..i^l2SlMt.......... ..QltU.. ............ l.C. a<.l'....... w.K.>.. nQa.. ............. le w...............9 .. .. .. .. .... ............. .. ... , ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~.. _ ... .... __A..-.............................. CHAPTER II PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1 ROUTE ALTERNATIVES In conjunction with the Natural Gas Parallel Pipeline Project, PTT requested that Bechtel International,Inc. -

Risk Assessment of Agricultural Affected by Climate Change: Central Region of Thailand

International Journal of Applied Computer Technology and Information Systems: Volume 10, No.1, April 2020 - September 2020 Risk Assessment of Agricultural Affected by Climate Change: Central Region of Thailand Pratueng Vongtong1*, Suwut Tumthong2, Wanna Sripetcharaporn3, Praphat klubnual4, Yuwadee Chomdang5, Wannaporn Suthon6 1*,2,3,4,5,6 Faculty of Science and Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Suvarnabhumi, Ayutthaya, Thailand e-mail: 1*[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract — The objective of this study are to create a changing climate, the cultivation of Thai economic risk model of agriculture with the Geo Information crops was considerably affected [2] System (GIS) and calculate the Agricultural In addition, the economic impact of global Vulnerability Index ( AVI) in Chainat, Singburi, Ang climate change on rice production in Thailand was Thong and Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya provinces by assessed [3] on the impact of climate change. The selecting factors from the Likelihood Vulnerability results of assessment indicated that climate change Index (LVI) that were relevant to agriculture and the affected the economic dimension of rice production in climate. The data used in the study were during the year Thailand. Both the quantity of production and income 1986-2016 and determined into three main components of farmers. that each of which has a sub-component namely: This study applied the concept of the (1)Exposure -

24/7 Emergency Operation Center for Flood, Storm and Landslide

No. 17/2011, Saturday September 10, 2011, 11:00 AM 24/7 Emergency Operation Center for Flood, Storm and Landslide DATE: Saturday, September 10, 2011 TIME: 09.00 LOCATION: Meeting Room 2, Ministry of Interior CHAIRPERSON: Mr. Chatpong Chatraphuti Deputy Director-General, Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation 1. CURRENT SITUATION 1.1 Current flooded provinces: there are 14 recent flooded provinces: Sukhothai, Phichit, Phitsanulok, Nakhon Sawan, Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, Ang Thong, Chai Nat, Ubon Ratchathani, Sing Buri, Nakhon Pathom,, Suphan Buri, Nonthaburi, Uthai Thani and Chacheongsao. The total of 65 Districts, 483 Sub-Districts, 2,942 Villages, 186,045 families and/or 476,775 people are affected by the flood. The total fatalities are 72 deaths and 1 missing. (Fatalities: 1 in Udon Thani, Sakon Nakhon, Uttaradit, Phetchabun, Suphan Buri; 2 in Tak, Nakhon Phanom, Roi Et, and Phang-Nga; 3 in Chiang Mai; 4 in Prachin Buri, Nakhon Sawan; 5 in Phitsanulok; 7 in Mae Hong Son and Sukhothai; 8 in Phrae; and 21 in Phichit: Missing: 1 in Mae Hong Son due to landslide) 1.2 Weather Condition: The active monsoon trough lies over the Central, Northeast and East of Thailand. The strong southwest monsoon prevails over the Andaman Sea, southern Thailand and the Gulf of Thailand. Torrential rain is likely over upper Thailand and isolated heavy to very heavy falls in the Northeast and the East. People in the low land and the riverside in the Central and the East should beware of flooding during the period. (Thai Meteorological Department : TMD) 1.3 Amount of Rainfall: The heaviest rainfall in the past 24 hours is at Phubphlachai District, Burirum Province at 126.5 mm. -

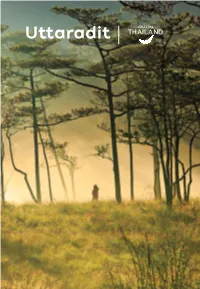

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit Namtok Sai Thip CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 8 Amphoe Mueang Uttaradit 8 Amphoe Laplae 11 Amphoe Tha Pla 16 Amphoe Thong Saen Khan 18 Amphoe Nam Pat 19 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 23 LOCAL PRODUCTS AND SOUVENIRS 25 INTERESTING ACTIVITIES 27 Agro-tourism 27 Golf Course 27 EXAMPLES OF TOUR PROGRAMMES 27 FACILITIES IN UTTARADIT 28 Accommodations 28 Restaurants 30 USEFUL CALLS 32 Wat Chedi Khiri Wihan Uttaradit Uttaradit has a long history, proven by discovery South : borders with Phitsanulok. of artefacts, dating back to pre-historic times, West : borders with Sukhothai. down to the Ayutthaya and Thonburi periods. Mueang Phichai and Sawangkhaburi were HOW TO GET THERE Ayutthaya’s most strategic outposts. The site By Car: Uttaradit is located 491 kilometres of the original town, then called Bang Pho Tha from Bangkok. Two routes are available: It, which was Mueang Phichai’s dependency, 1. From Bangkok, take Highway No. 1 and No. 32 was located on the right bank of the Nan River. to Nakhon Sawan via Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, It flourished as a port for goods transportation. Ang Thong, Sing Buri, and Chai Nat. Then, use As a result, King Rama V elevated its status Highway No. 117 and No. 11 to Uttaradit via from Tambon or sub-district into Mueang or Phitsanulok. town but was still under Mueang Phichai. King 2. From Bangkok, drive to Amphoe In Buri via Rama V re-named it Uttaradit, literally the Port the Bangkok–Sing Buri route (Highway No. of the North. Later Uttaradit became more 311). -

4. Counter-Memorial of the Royal Government of Thailand

4. COUNTER-MEMORIAL OF THE ROYAL GOVERNMENT OF THAILAND I. The present dispute concerns the sovereignty over a portion of land on which the temple of Phra Viharn stands. ("PhraViharn", which is the Thai spelling of the name, is used throughout this pleading. "Preah Vihear" is the Cambodian spelling.) 2. According to the Application (par. I), ThaiIand has, since 1949, persisted in the occupation of a portion of Cambodian territory. This accusation is quite unjustified. As will be abundantly demon- strated in the follo~vingpages, the territory in question was Siamese before the Treaty of 1904,was Ieft to Siam by the Treaty and has continued to be considered and treated as such by Thailand without any protest on the part of France or Cambodia until 1949. 3. The Government of Cambodia alleges that its "right can be established from three points of rieivJ' (Application, par. 2). The first of these is said to be "the terms of the international conventions delimiting the frontier between Cambodia and Thailand". More particuIarly, Cambodia has stated in its Application (par. 4, p. 7) that a Treaty of 13th February, 1904 ". is fundamental for the purposes of the settlement of the present dispute". The Government of Thailand agrees that this Treaty is fundamental. It is therefore common ground between the parties that the basic issue before the Court is the appIication or interpretation of that Treaty. It defines the boundary in the area of the temple as the watershed in the Dangrek mountains. The true effect of the Treaty, as will be demonstratcd later, is to put the temple on the Thai side of the frontier. -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received Bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 9 Au 14 Mai 1980 C Cases — Cas

Wkty Epldem. Bec.: No. 20 -16 May 1980 — 150 — Relevé éptdém. hebd : N° 20 - 16 mal 1980 Kano State D elete — Supprimer: Bimi-Kudi : General Hospital Lagos State D elete — Supprimer: Marina: Port Health Office Niger State D elete — Supprimer: Mima: Health Office Bauchi State Insert — Insérer: Tafawa Belewa: Comprehensive Rural Health Centre Insert — Insérer: Borno State (title — titre) Gongola State Insert — Insérer: Garkida: General Hospital Kano State In se rt— Insérer: Bimi-Kudu: General Hospital Lagos State Insert — Insérer: Ikeja: Port Health Office Lagos: Port Health Office Niger State Insert — Insérer: Minna: Health Office Oyo State Insert — Insérer: Ibadan: Jericho Nursing Home Military Hospital Onireke Health Office The Polytechnic Health Centre State Health Office Epidemiological Unit University of Ibadan Health Services Ile-Ife: State Hospital University of Ife Health Centre Ilesha: Health Office Ogbomosho: Baptist Medical Centre Oshogbo : Health Office Oyo: Health Office DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received bom 9 to 14 May 1980 — Notifications reçues du 9 au 14 mai 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres non encore disponibles D Deaths — Décès / Imported cases — Cas importés P t o n r Revised figures — Chifircs révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects CHOLERA — CHOLÉRA C D YELLOW FEVER — FIÈVRE JAUNE ZAMBIA — ZAMBIE 1-8.V Africa — Afrique Africa — Afrique / 4 0 C 0 C D \ 3r 0 CAMEROON. UNITED REP. OF 7-13JV MOZAMBIQUE 20-26J.V CAMEROUN, RÉP.-UNIE DU 5 2 2 Asia — Asie Cameroun Oriental 13-19.IV C D Diamaré Département N agaba....................... î 1 55 1 BURMA — BIRMANIE 27.1V-3.V Petté ........................... -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 14 to 20 March 1980 — Notifications Reçues Du 14 Au 20 Mars 1980

Wkty Epidem. Xec.: No. 12-21 March 1980 — 90 — Relevé êpittém. hetxl. : N° 12 - 21 mars 1980 A minor variant, A/USSR/50/79, was also submitted from Brazil. A/USSR/90/77 par le Brésil. Un variant mineur, A/USSR/50/79, a Among influenza B strains, B/Singapore/222/79-like strains were aussi été soumis par le Brésil. Parmi les souches virales B, des souches submitted from Trinidad and Tobago and B/Hong Kong/5/72-like similaires à B/Singapore/222/79 ont été soumises par la Trimté-et- from Brazil. Tobago et des souches similaires à B/Hong Kong/5/72 par le Brésil. C zechoslovakia (28 February 1980). — *1 The incidence of acute T chécoslovaquie (28 février 1980). — 1 Après la pointe de début respiratory disease in the Czech regions is decreasing after a peak in février 1980, l’incidence des affections respiratoires aigues est en early February 1980. In the Slovakian regions a sharp increase was diminution dans les régions tchèques. Dans les régions slovaques, seen at the end of January but, after a peak at the end of February, the une forte augmentation a été constatée fin janvier mais, après un incidence has been decreasing in all age groups except those 6-14 maximum fin février, l’incidence diminue dans tous les groupes years. All strains isolated from both regions show a relationship d'âge, sauf les 6-14 ans. Toutes les souches isolées dans les deux with A/Texas/1/77 (H3N2) although with some antigenic drift. régions sont apparentées à A/Texas/1/77 (H3N2), mais avec un certain glissement antigénique. -

Loan from Financial Institution

Annual Report 2020 Saksiam Leasing Public Company Limited December 8, 2020 Saksiam Leasing Public Company Limited by Dr. Suphot Singhasaneh (Chairman of the Board of Directors) Asst. Prof. Dr. Phoonsak Boonsalee (President of Executive Committee) Mr. Siwaphong Boonsalee (Managing Director) together with the directors, executives and employees witnessed the opening of the first day of trading on the Stock Exchange of Thailand.” Contents Part 1 Business Operations and Operating Results 4 Structure and Business Operation 32 Risk Management 41 Driving Business for Sustainability 45 Management Discussion and Analysis : MD&A 70 General Information and other Significant Information Part 2 Corporate Governance 73 Corporate Governance Policy 79 Management structure and key information relating to the Board of Committees, the Board of Sub-Committees, Executives, Employees and others 97 Key Operating Performance Report of Corporate Governance 111 Internal Control and Cross Transaction 121 Part 3 Financial Statements Attachment 182 Attachment 1 Profiles of Directors, Executives, Controlling Persons and Roles and Duties of the Board of Directors 199 Attachment 2 Profiles of the Board of Sub-Committees December 8, 2020 200 Attachment 3 Profiles of Head of Internal Audit Saksiam Leasing Public Company Limited by 201 Attachment 4 Assets Used in Business Operation and Assets Appraisal List Dr. Suphot Singhasaneh (Chairman of the Board of Directors) 208 Attachment 5 Corporate Governance Policy and Business Ethics Asst. Prof. Dr. Phoonsak Boonsalee (President -

Spatio-Temporal Diffusion Pattern and Hotspot Detection of Dengue in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand

Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 51-74; doi:10.3390/ijerph8010051 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health ISSN 1660-4601 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijerph Article Spatio-Temporal Diffusion Pattern and Hotspot Detection of Dengue in Chachoengsao Province, Thailand Phaisarn Jeefoo 1,*, Nitin Kumar Tripathi 1 and Marc Souris 1,2,3 1 Remote Sensing and GIS Field of Study, School of Engineering and Technology, Asian Institute of Technology, P.O. Box 4, Klong Luang, Pathumthani 12120, Thailand; E-Mails: [email protected] (N.K.T.); [email protected] (M.S.) 2 Center of Excellence for Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Salaya, Nakhompathom 73170, Thailand 3 Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), UMR 190, Marseille, France * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +66-2524-5799; Fax: +66-2524-5597. Received: 3 November 2010; in revised form: 20 December 2010 / Accepted: 21 December 2010 / Published: 29 December 2010 Abstract: In recent years, dengue has become a major international public health concern. In Thailand it is also an important concern as several dengue outbreaks were reported in last decade. This paper presents a GIS approach to analyze the spatial and temporal dynamics of dengue epidemics. The major objective of this study was to examine spatial diffusion patterns and hotspot identification for reported dengue cases. Geospatial diffusion pattern of the 2007 dengue outbreak was investigated. Map of daily cases was generated for the 153 days of the outbreak. Epidemiological data from Chachoengsao province, Thailand (reported dengue cases for the years 1999–2007) was used for this study. -

Notam List Series J

THAILAND NOTAM LIST INTERNATIONAL NOTAM OFFICE SERIES J Telephone : +66 2287 8202 AERONAUTICAL INFORMATION MANAGEMENT CENTRE AFS : VTBDYNYX AERONAUTICAL RADIO OF THAILAND Facsimile : +66 2287 8205 REFERENCE NO. VTBDYNYX P.O.BOX 34 DON MUEANG E-MAIL : [email protected] 02/21 www.aerothai.co.th BANGKOK 10211 THAILAND 01 FEB 2021 TheAEROTHAI following : www.aerothai.co.th NOTAM series J were still valid on 01 FEB 2021, NOTAM not included have either been cancelled, time expired or superseded by AIP supplement or incorporated in the AIP-THAILAND. VTBB (BANGKOK (ACC/FIC/COM CENTRE)) J5814/20 2011300510/2102281100 VT R3 ACT LOWER LIMIT: GND UPPER LIMIT: 6000FT AMSL J6045/20 2101010200/2103310900 DLY 0200-0300, 0400-0500, 0600-0700 AND 0800-0900 PJE WILL TAKE PLACE RADIUS 3NM CENTRE 130825N1010248E (SI RACHA DISTRICT CHON BURI PROVINCE) LOWER LIMIT: GND UPPER LIMIT: FL130 J6046/20 2101010100/2103311100 DLY 0100-1100 PJE WILL TAKE PLACE RADIUS 3NM CENTRE 130825N1010248E (SI RACHA DISTRICT CHON BURI PROVINCE) LOWER LIMIT: GND UPPER LIMIT: 9000FT AMSL J6066/20 2012310245/2103311659 TEMPO RESTRICTED AREA ACT RADIUS 1NM CENTRE 123823N1011931E (MUEANG DISTRICT RAYONG PROVINCE) LOWER LIMIT: GND UPPER LIMIT: 7000FT AGL J6067/20 2101010100/2103311100 DLY 0100-1100 PJE WILL TAKE PLACE RADIUS 3NM CENTRE 124238N1013740E (KLAENG DISTRICT RAYONG PROVINCE) GND/FL130 J0057/21 2102212300/2102261130 DLY 2300-1130 GUN FRNG WILL TAKE PLACE WI AREA 145710N1004042E- 145526N1004357E-145624N1004112E- 145710N1004042E (MUEANG DISTRICT LOP BURI PROVINCE) LOWER LIMIT: -

Thailand Human Development Report 2003 Thailand Human Development Report 2003

THAILAND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2003 THAILAND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2003 THAILAND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2003 United Nations Development Programme The cover photo shows a huge stage poster of the Assembly of the Poor (AOP)’s rally in front of the Government House that says “Assembly of the Poor follows up on the (Government’s) promises”. On the wrist is written “United like sticky rice, together as one for the victory”. The placards mention various problems and issues that AOP have campaigned for or against, e.g. dams, forest-land, alternative agriculture, state’s projects, fake pigs-cows. Photo credit: Friends of the People (FOP) Copyright © 2003 United Nations Development Programme Rajdamnern Nok Avenue Bangkok 10200 Thailand Tel: (66-2) 2882130 Fax: (66-2) 2800556 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.undp.or.th ISBN: 974-91116-5-6 ii THAILAND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2003 FOREWORD His Excellency Thaksin Shinawatra Prime Minister of Thailand It is my pleasure and honour to introduce the second UNDP National Human Develop- ment Report of Thailand. At the beginning of the new millennium, all nations are eager to focus on poverty alleviation in its broadest sense, not just from an economic and technical perspective as tended to be the case during most of the 20th century. UNDP’s focus on “human development” provides an excellent framework for this broader approach and matches well with Thailand’s own “people-centred approach” to development. Globalization has tended to divert attention from this broader perspective, focusing too often exclusively on economic growth and its attendant opportunities.