An Interview with Kee Thuan Chye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Feminist Dialogics Approach in Reading Kee Thuan Chye's Plays

3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies – Vol 22(1): 97 – 109 Reclaiming Voices and Disputing Authority: A Feminist Dialogics Approach in Reading Kee Thuan Chye’s Plays ERDA WATI BAKAR School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia [email protected] NORAINI MD YUSOF School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia RAVICHANDRAN VENGADASAMY School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia ABSTRACT Kee Thuan Chye in all four of his selected plays has appropriated and reimagined history by giving it a flair of contemporaneity in order to draw a parallel with the current socio-political climate. He is a firm believer of freedom of expression and racial equality. His plays become his didactic tool to express his dismay and frustration towards the folly and malfunctions in the society. He believes that everybody needs to rise and eliminate their fear from speaking their minds regardless of race, status and gender. In all four of his plays, Kee has featured and centralised his female characters by empowering them with voice and agency. Kee gives fair treatment to his women by painting them as strong, liberated, determined and fearless beings. Armed with the literary tools of feminist dialogics which is derived from Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism and strategies of historical re-visioning, this study investigates and explores Kee’s representations of his female characters and the various ways that he has liberated them from being passive and silent beings as they contest the norms, values and even traditions. -

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2010(025927) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2010:Vol.30No.6 Aliran Monthly : Vol.30(6) Page 1 A change is going to come sing my beloved country a change is going to come when the hornbill flies from the white-haired rajah and the dog's head comes to its senses from Kinabalu to the Kinta Valley the monsson flood will cleanse the dirt list, Gilgamesh, to the words of Utnapishtun resore the order of Hammurabi the tainted and the greedy will be swept away and the earth will swallow the rent collectors arise my beloved country a change is going to come when the ghosts of the murdered are finally appeased and we dance on the graves of unjust judges embrace the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace where no one calls himself a lord go forth, Yuanzhang, make bright the light that shines for Umar on his nightly rounds as he seeks out the hungry and cares for the weak while the city sleeps in the lap of justice rejoice my beloved country a change is going to come when the immigrant sheds the skin of the lion and becomes his genuine self again the scales that are gaulty will no more serve to weight out favours in unequal parts give us instead Ashoka's wheel, his welcome to all faiths, his love for all children Martin will see the promised land and the imam will sit down with priest a change is going to come, my beloved country, so sing, arise, rejoice Kee Thuan Chye May 2010 Kuala Lumpur Written specially for Aliran Dinner 26 June 2010 Aliran Monthly : Vol.30(6) Page 2 EDITOR'S NOTE Challenges to press freedom have emerged as oppo- sition parties run into difficulties in renewing per- CONTENTS mits for their party newspapers. -

Cultural Policies to the Creation of Nation-States in the Former Colonies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS THE POLITICS OF DRAMA: POST-1969 STATE POLICIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THEATRE IN ENGLISH IN MALAYSIA FROM 1970 TO 1999. VELERIE KATHY ROWLAND (B.A. ENG.LIT. (HONS), UNIVERSITY MALAYA) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Theatre practice is largely undocumented in Malaysia. Without the many practitioners who gave of their time, and their valuable theatre programme collections, my efforts to piece together a chronology of theatre productions would not have been possible. Those whose contribution greatly assisted in my research include Ivy Josiah, Chin San Sooi, Thor Kah Hoong, Datuk Noordin Hassan, Datuk Syed Alwi, Marion D’Cruz, Shanti Ryan, Mano Maniam, Mervyn Peters, Susan Menon, Noorsiah Sabri, Sabera Shaik, Faridah Merican, Huzir Sulaiman, Jit Murad, Kee Thuan Chye, Najib Nor, Normah Nordin, Rosmina Tahir, Zahim Albakri and Vijaya Samarawickram. I received tremendous support from Krishen Jit, whose probing intellectualism coupled with a historian’s insights into theatre practice, greatly benefited this work. The advice, feedback and friendship of Jo Kukathas, Wong Hoy Cheong, Dr. Sumit Mandal, Dr. Tim Harper, Jenny Daneels, Rahel Joseph, Adeline Tan and Eddin Khoo are also gratefully acknowledged. The three years spent researching this work would not have been possible without the research scholarship awarded by the National University of Singapore. For this I wish to thank Dr. Ruth Bereson, for her support and advice during the initial stages of application. I also wish to thank Prof. -

Malaysian Literature in English

Malaysian Literature in English Malaysian Literature in English: A Critical Companion Edited by Mohammad A. Quayum Malaysian Literature in English: A Critical Companion Edited by Mohammad A. Quayum This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Mohammad A. Quayum and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4929-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4929-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Mohammad A. Quayum Chapter One .............................................................................................. 12 Canons and Questions of Value in Literature in English from the Malayan Peninsula Rajeev S. Patke Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 29 English in Malaysia: Identity and the Market Place Shirley Geok-lin Lim Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 57 Self-Refashioning a Plural Society: Dialogism and Syncretism in Malaysian Postcolonial Literature Mohammad -

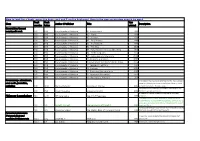

MCG Library Book List Excel 26 04 19 with Worksheets Copy

How to look for a book: press the keys cmd and F on the keyboard, then in the pop up window search by word Book Book Year Class Author / Publisher Title Description number letter printed Generalities/General encyclopedic work 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 01- Environment 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 02 - Plants 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 03 - Animals 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 04 - Early History 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 05 - Architecture 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 06 - The Seas 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 07 - Early Modern History (1800-1940) 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 08 - Performing Arts 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 09 - Languages and Literature 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 10- Religions and Beliefs 2005 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 11-Government and Politics (1940-2006) 2006 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 12- Peoples & Traditions 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 13- Economy 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 14- Crafts and the visual arts 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 15- Sports and Recreation 2008 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 16- The rulers of Malaysia 2011 Documentary-, educational-, In this book Marina draws attention to the many dangers news media, journalism, faced by Malaysia, to concerns to fellow citizens, social publishing 070 MAR Marina Mahathir Dancing on Thin Ice 2015 and political affairs. Double copies. Compilations of he author's thought, reflecting on the 070 RUS Rusdi Mustapha Malaysian Graffiti 2012 World, its people and events. Principles of Tibetan Buddhism applied to everyday Philosopy & psychology 100 LAM HH Dalai Lama The Art of Happiness 1999 problems As Nisbett shows in his book people think about and see the world differently because of differing ecologies, social structures, philosophies and educational systems that date back to ancient 100 NIS Nisbett, Richard The Geography of thought 2003 Greece and China. -

WINTER 2020 SCHEDULE January 6 - March 13

WINTER 2020 SCHEDULE January 6 - March 13 Registration OPENS Monday, November 18, 2019 at 10:00am. Stagebridge: PAI Winter 2020 Frequently Asked Questions What is Stagebridge? Stagebridge’s mission is to transform the lives of older adults and their communities through the performing arts. Stagebridge uses the performing arts to change the way people view and experience aging. For more than 40 years, our innovative workshops and critically acclaimed performances have had a dramatic and wide-ranging impact on the lives of seniors and their communities. Are there qualifications or prerequisites for taking a class? No. Most of our classes are open to everyone of all levels. We have a few audition-only touring and performing groups. Where and when are classes held? Classes meet weekdays at the First Congregational Church of Oakland, 2501 Harrison Street, Oakland, CA 94612. How much is the tuition? Tuition is generally between $100-$300 per class each 8-10 week session. Scholarships and payment plans are also available. How long are most of the classes? Classes are typically 2 hours per week for 10 weeks. There are 3 sessions each year: Fall, Winter, and Spring. A shorter summer session is also offered. Can I observe a class before signing up? Yes. You can attend the first meeting of any class for free. You can sign up, pay a $75.00 deposit or make a full payment for a class and, if you change your mind, request a refund before the second week begins. Is your building accessible? Our building is wheelchair accessible, and we are always happy to talk to students about accessibility of the space and specific classes. -

Manglish by Just Going Through This Book

8.8mm lee su kim The classic bestseller now in a brand new edition For Review only Aiseh! Malaysians talk one kind one, you know? You also can or not? If cannot, don’t worry, you can learn & Got chop or not? stephen j. hall No chop cannot. how to be terror at Manglish by just going through this book. The authors Lee Su Kim and Stephen Hall have come up with a damn shiok and kacang putih way for anybody to master Manglish. Nohnid to vomit blood. Some more ah, this new edition got extra chapters and new Manglish words. So don’t be a bladiful and miss DOCUMENT AH CHONG & SONS out on this. Get a copy and add oil to your social life. – Kee Thuan Chye, author of The People’s Victory Now back after 20 years with brand new words, expressions and idioms, this hilarious classic remains packed with humour, irreverence and loads of fun. It bids all Malaysians to lighten up, laugh at ourselves and revel in our unique, multicultural way of life. MANGLISH MANGLISH Forget about tenses, grammar, pronunciation, and just relek lah … Aiyoh. Manglish or Malaysian English is what Malaysians speak MALAYSIAN ENGLISH when we want to connect with each other or just hang loose. Borrowing from Malay, Chinese, Indian, Asli, British English, AT ITS WACKIEST! American English, dialects, popular mass media and plenty more, our unique English reflects our amazing diversity. Like a frothy teh tarik or a lip-smacking mouthful of divine durian, Manglish is uniquely Malaysian. Those two, tak ngam lah! Manglish is an entertaining, funny and witty compilation of commonly used Malaysian English words and expressions. -

Malaysian Literature in English: an Evolving Tradition

Kunapipi Volume 25 Issue 2 Article 17 2003 Malaysian Literature in English: An Evolving Tradition Mohammad A. Quayum Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Quayum, Mohammad A., Malaysian Literature in English: An Evolving Tradition, Kunapipi, 25(2), 2003. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol25/iss2/17 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Malaysian Literature in English: An Evolving Tradition Abstract Introduction In spite of the many early challenges and lingering difficulties facedy b writers in the English language in Malaysia — challenges and difficulties of a political, literary and social nature — literary tradition in English in this newly emergent nation has come a long way, showing considerable dynamism and resilience since its inception. Critics suggest that the literarture in English in post-colonial societies generally evolves in three stages. In The Empire Writes Back: Theoiy and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, for example, explain these three stages as: (i) ‘[works] produced by “representatives” of the imperial power’; (ii) ‘[works] produced “under imperial license” by “natives” or “outcastes” ’; and finally, (iii) the ‘development of independent literatures’ or the ‘emergence of modem post-colonial literatures’ (5-6). This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol25/iss2/17 178 MOHAMMAD A. QUAYUM Malaysian Literature in English: An Evolving Tradition Introduction In spite of the many early challenges and lingering difficulties faced by writers in the English language in Malaysia — challenges and difficulties of a political, literary and social nature — literary tradition in English in this newly emergent nation has come a long way, showing considerable dynamism and resilience since its inception. -

The Malaysian Albatross of May 13, 1969 Racial Riots

The Malaysian Albatross of May 13, 1969 Racial Riots Malachi Edwin VETHAMANI University of Nottingham Malaysia1 Introduction RACIAL riots in Malaysia are an uncommon phenomenon though there is a constant reminder and threat that the 13 May 1969 riots could recur. The 13 May, 1969 racial riots remains a deep scar in the nation’s psyche even today and the fear of such a re- occurrence continues to loom especially when some unscrupulous Malay politicians remind the nation that such an eventuality is a possibility if the privileged position of Malays is threatened. Yet, Malaysia has prided itself as a model for multi-cultural and multi-racial harmony in its sixty over years of existence as a nation. However, its attempts at forging a Malaysian race of “Bangsa Malaysia” (Mahathir 1992: 1) has not been achieved. In recent post-colonial nations, especially in nations with mixed populations like Malaysia, a lot of effort is put into projecting a national culture or a national identity. This attempt to forge various races into a single cultural entity is an impossibility, and it is a misconception that there can be a single national culture. As Ahmad says, any nation comprises cultures not just one culture. He asserts that it is a mistaken notion that “each ‘nation’ of the ‘Third World’ has a ‘culture’ and a ‘tradition’” (9). This paper examines Malaysian writers’ creative response in the English language to the 13 May, 1969 riots. It presents a brief historical context to the violent event and political response to the event which has resulted in the passing of various policies and laws that has impacted not only on the re-structuring of Malaysian society but also the management of the relationships among the multi-ethnic communities in the country. -

Kee Thuan Chye, No More Bullshit, Please, We're All Malaysians

ASIATIC, VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2012 Kee Thuan Chye, No More Bullshit, Please, We’re All Malaysians. Kuala Lumpur: Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2012. 401 pp. ISBN 9814382019. In No More Bullshit, Please, We’re All Malaysians, Kee Thuan Chye offers insight into a range of sociopolitical issues that impact contemporary Malaysia. Although most of the multigenre work in this volume appeared previously in various publications, compiling Kee’s work allows the reader to gain a greater sense of key topics over a period of several years. On the other hand, readers who may not be as familiar with the nuances of Malaysian politics and its political figures will need to do some homework. The items in No More Bullshit, Please, We’re All Malaysians once ran in online sources or papers such as MalaysianDigest.com, Free Malaysia Today or Penang Monthly. Kee also pulls snippets from his plays, including The Swordfish, then the Concubine, not to mention noteworthy poems and talks. One poem, “A Change is Going to Come,” was performed at a dinner at the Petaling Jaya Civic Centre; another published talk took place at a human rights forum. Kee organises the pieces by thematic, not chronological, order, taking care to note that earlier works still hold relevance in today’s Malaysia (103). Some of his work, including one poem and a play, were written at least partly in the 1980s. Other pieces ran as late as the end of 2011, but most appeared in the early twenty-first century. While some sections dwell on leaders Mahathir Mohamad and Najib Razak, others focus on religion, race, the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and the Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC). -

West Meets East in Malaysia and Singapore. Participants' Papers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 698 SO 031 674 TITLE West Meets East in Malaysia and Singapore. Participants' Papers. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program1999 (Malaysia and Singapore). INSTITUTION Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. SPONS AGENCY Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 347p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) Guides Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; Art Education; Asian Studies; *Cultural Awareness; Developing Nations; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Higher Education; *Political Issues; Social Studies; Study Abroad; Undergraduate Study IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia; *Singapore ABSTRACT These projects were completed by participants in the Fulbright-Hays summer seminar in Malaysia and Singapore in 1999.The participants represented various regions of the U.S. anddifferent grade levels and subject areas. The seminar offered a comprehensiveoverview of how the people of Malaysia and Singapore live, work, and strivetowards their vision of a more secure east-west relationship withoutsacrificing their history or culture. In addition, seminars were presentedabout Malaysia's geography and history, the political structure, culturalplurality, religions, economy, educational system, aspirations and goalsfor the future, and contemporary issues facing the society. The 15 projects' are: (1) "Rice Cultivation of Malaysia" (Klaus J. Bayr); (2) "Mahathir of Malaysia" (Larry G. Beall); (3) "The Politics of Development of Malaysia: A Five Week Course Segment for an Undergraduate Course on Politics inDeveloping Areas" (George P. Brown); (4) "Patterns of Urban Geography: A Comparison of Cities in Southeast Asia and the United States" (Robert J. Czerniak); (5) "The Domestic and Foreign Effects of the Politics of Modernization inMalaysia" (Henry D. -

Rewriting of the Malay Myth

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Image-i-nation and fictocriticism: rewriting of the Malay myth Nasirin Bin Abdillah University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Bin Abdillah, Nasirin, Image-i-nation and fictocriticism: rewriting of the Malay myth, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2016.