Malaysian Literature in English: an Evolving Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Feminist Dialogics Approach in Reading Kee Thuan Chye's Plays

3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies – Vol 22(1): 97 – 109 Reclaiming Voices and Disputing Authority: A Feminist Dialogics Approach in Reading Kee Thuan Chye’s Plays ERDA WATI BAKAR School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia [email protected] NORAINI MD YUSOF School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia RAVICHANDRAN VENGADASAMY School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia ABSTRACT Kee Thuan Chye in all four of his selected plays has appropriated and reimagined history by giving it a flair of contemporaneity in order to draw a parallel with the current socio-political climate. He is a firm believer of freedom of expression and racial equality. His plays become his didactic tool to express his dismay and frustration towards the folly and malfunctions in the society. He believes that everybody needs to rise and eliminate their fear from speaking their minds regardless of race, status and gender. In all four of his plays, Kee has featured and centralised his female characters by empowering them with voice and agency. Kee gives fair treatment to his women by painting them as strong, liberated, determined and fearless beings. Armed with the literary tools of feminist dialogics which is derived from Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism and strategies of historical re-visioning, this study investigates and explores Kee’s representations of his female characters and the various ways that he has liberated them from being passive and silent beings as they contest the norms, values and even traditions. -

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences

THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA ISSN 0219-3213 TRS15/21s ISSUE ISBN 978-981-5011-00-5 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace 15 Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 7 8 9 8 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 5 2021 21-J07781 00 Trends_2021-15 cover.indd 1 8/7/21 12:26 PM TRENDS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 1 9/7/21 8:37 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Singapore APEC Study Centre and the Temasek History Research Centre (THRC). ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 2 9/7/21 8:37 AM THE UNREALIZED MAHATHIR-ANWAR TRANSITIONS Social Divides and Political Consequences Khoo Boo Teik ISSUE 15 2021 21-J07781 01 Trends_2021-15.indd 3 9/7/21 8:37 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2021 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

Interrogating Malaysian Literature in English: Its Glories, Sorrows and Thematic Trends

Kunapipi Volume 30 Issue 1 Article 13 2008 Interrogating Malaysian literature in English: Its glories, sorrows and thematic trends Mohammad Quayum Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Quayum, Mohammad, Interrogating Malaysian literature in English: Its glories, sorrows and thematic trends, Kunapipi, 30(1), 2008. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol30/iss1/13 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Interrogating Malaysian literature in English: Its glories, sorrows and thematic trends Abstract Malaysian literature in English has just attained its sixtieth anniversary since its modest inception in the late 1940s, initiated by a small group of college and university students in Singapore. Singapore was the academic hub of British Malaya and the only university of the colony was located there, therefore it was natural that a movement in English writing should have started from there. Nonetheless, given the current cultural and political rivalries between Singapore and Malaysia, it is rather ironic that a Malaysian tradition of writing started in a territory that now sees Malaysia as the ‘other’. This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol30/iss1/13 149 MoHAMMAD QuayUm Interrogating Malaysian Literature in English: Its Glories, Sorrows and Thematic Trends Malaysian literature in English has just attained its sixtieth anniversary since its modest inception in the late 1940s, initiated by a small group of college and university students in Singapore. -

Sufism in Writings: Mysticism and Spirituality in the Love Poems of Salleh Ben Joned

International Journal of Comparative Literature & Translation Studies ISSN 2202-1817 (Print), ISSN 2202-1825 (Online) Vol. 1 No. 2; July 2013 Copyright © Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Sufism in Writings: Mysticism and Spirituality in the Love Poems of Salleh Ben Joned Nadiah Abdol Ghani Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication University Putra Malaysia Received: 30-05- 2013 Accepted: 30-06- 2013 Published: 31-07- 2013 doi:10.7575/aiac.ijclts.v.1n.2p.33 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijclts.v.1n.2p.33 Abstract Salleh Ben Joned is seen as a notorious figure in the Malaysian literary scene as a result of his use of profanities and vulgarities, interlacing them into ideas or texts that are seen to be sacred by the society. He is most infamously known for his vivid descriptions of carnal images and sex and its vicissitudes in his poems, thus earning the accusations of being an apostate and his works to be blasphemous. This essay is an attempt at reappraising his love poetry, by explicating the poems using the doctrine of Sufism and its central theme of love and the Beloved/Divine. My view is that his poems are not just describing the ‘profane’ act of sexual copulation, but rather would be more apt in describing a devotee’s spiritual journey towards finding his Beloved or the Divine. Keywords: Salleh Ben Joned, Sacred, Profane, Sufism, Poetry, Love 1. Love Poetry of Salleh Ben Joned In contemporary studies of modern Malaysian literature, Salleh Ben Joned occupies a unique place in the literary imagination of the nation. -

Km34022016 02.Pdf

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 34, No. 2, 2016, 25–58 THE MARGINALISATION OF MALAYSIAN TEXTS IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE CURRICULUM AND ITS IMPACT ON SOCIAL COHESION IN MALAYSIAN CLASSROOMS Shanthini Pillai*, P. Shobha Menon and Ravichandran Vengadasamy School of Language Studies and Linguistics, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, MALAYSIA *Corresponding author: [email protected]/[email protected] To cite this article: Shanthini Pillai, P. Shobha Menon and Ravichandran Vengadasamy. 2016. The marginalisation of Malaysian texts in the English language curriculum and its impact on social cohesion in Malaysian classrooms. Kajian Malaysia 34(2): 25–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.21315/ km2016.34.2.2 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.21315/ km2016.34.2.2 ABSTRACT In this paper, we seek to investigate the place that local literature has been given in Malaysian Education in the English Language Subject for Secondary Schools in Malaysia. We argue that literature engenders a space for the nation to share in the experiences and feelings of groups and situations that might never be encountered directly. It often engages with the realities of a nation through diverse constructions of its history, its realities and communal relations. As such we posit that literature can be a significant tool to study the realities of Malaysian nationhood and its constructions of inter-ethnic relationships, and ultimately, an effective tool to forge nation building. The discussion focuses on investigating the role that literature has played in Malaysian education in the context of engaging with ethnically diverse Malaysian learners and whether text selection has prioritised ethnic diversity in its Malaysian context. -

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2010(025927) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2010:Vol.30No.6 Aliran Monthly : Vol.30(6) Page 1 A change is going to come sing my beloved country a change is going to come when the hornbill flies from the white-haired rajah and the dog's head comes to its senses from Kinabalu to the Kinta Valley the monsson flood will cleanse the dirt list, Gilgamesh, to the words of Utnapishtun resore the order of Hammurabi the tainted and the greedy will be swept away and the earth will swallow the rent collectors arise my beloved country a change is going to come when the ghosts of the murdered are finally appeased and we dance on the graves of unjust judges embrace the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace where no one calls himself a lord go forth, Yuanzhang, make bright the light that shines for Umar on his nightly rounds as he seeks out the hungry and cares for the weak while the city sleeps in the lap of justice rejoice my beloved country a change is going to come when the immigrant sheds the skin of the lion and becomes his genuine self again the scales that are gaulty will no more serve to weight out favours in unequal parts give us instead Ashoka's wheel, his welcome to all faiths, his love for all children Martin will see the promised land and the imam will sit down with priest a change is going to come, my beloved country, so sing, arise, rejoice Kee Thuan Chye May 2010 Kuala Lumpur Written specially for Aliran Dinner 26 June 2010 Aliran Monthly : Vol.30(6) Page 2 EDITOR'S NOTE Challenges to press freedom have emerged as oppo- sition parties run into difficulties in renewing per- CONTENTS mits for their party newspapers. -

K S Maniam: Malaysian Writer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Southern Queensland ePrints Complete Citation: Wicks, Peter (2007). K S Maniam (1942-). The Literary Encyclopedia, 16 April 2007. ISSN 1747-678X. Accessed from USQ ePrints http://eprints.usq.edu.au K S MANIAM: MALAYSIAN WRITER Peter Wicks University of Southern Queensland K S Maniam is a prolific writer, with three novels, plays, and numerous short stories to his credit. An intense, reserved, yet courteous person, he lives with his wife and children in a modest, two-storeyed house in Subang, one of the dormitory suburbs of Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. It was my privilege to visit him there, and to engage in the discussions on which this profile draws. Despite his critically-acclaimed literary achievements, Maniam is denied official recognition and public acclaim in his country of birth because he chooses to write in English, rather than the national language known as Bahasa Malaysia. Yet there are valid reasons for his choice of literary medium, reasons that are inherent in Malaysia's modern history as former British colony and now independent state to which immigrant communities have made a vital contribution. Nor does his use of English render him less authentic a Malaysian than his literary counterparts in that country. Indeed, his works are imbued with the vibrancy of the Malaysian landscape, both human and physical. ************************************* Born Subramaniam Krishnan in 1942, K S Maniam is of Hindu, Tamil and working-class background. His birthplace was Bedong, a small town in Kedah situated in the rural north of Malaysia. -

Cultural Policies to the Creation of Nation-States in the Former Colonies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS THE POLITICS OF DRAMA: POST-1969 STATE POLICIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THEATRE IN ENGLISH IN MALAYSIA FROM 1970 TO 1999. VELERIE KATHY ROWLAND (B.A. ENG.LIT. (HONS), UNIVERSITY MALAYA) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Theatre practice is largely undocumented in Malaysia. Without the many practitioners who gave of their time, and their valuable theatre programme collections, my efforts to piece together a chronology of theatre productions would not have been possible. Those whose contribution greatly assisted in my research include Ivy Josiah, Chin San Sooi, Thor Kah Hoong, Datuk Noordin Hassan, Datuk Syed Alwi, Marion D’Cruz, Shanti Ryan, Mano Maniam, Mervyn Peters, Susan Menon, Noorsiah Sabri, Sabera Shaik, Faridah Merican, Huzir Sulaiman, Jit Murad, Kee Thuan Chye, Najib Nor, Normah Nordin, Rosmina Tahir, Zahim Albakri and Vijaya Samarawickram. I received tremendous support from Krishen Jit, whose probing intellectualism coupled with a historian’s insights into theatre practice, greatly benefited this work. The advice, feedback and friendship of Jo Kukathas, Wong Hoy Cheong, Dr. Sumit Mandal, Dr. Tim Harper, Jenny Daneels, Rahel Joseph, Adeline Tan and Eddin Khoo are also gratefully acknowledged. The three years spent researching this work would not have been possible without the research scholarship awarded by the National University of Singapore. For this I wish to thank Dr. Ruth Bereson, for her support and advice during the initial stages of application. I also wish to thank Prof. -

Malaysian Literature in English

Malaysian Literature in English Malaysian Literature in English: A Critical Companion Edited by Mohammad A. Quayum Malaysian Literature in English: A Critical Companion Edited by Mohammad A. Quayum This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Mohammad A. Quayum and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4929-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4929-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Mohammad A. Quayum Chapter One .............................................................................................. 12 Canons and Questions of Value in Literature in English from the Malayan Peninsula Rajeev S. Patke Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 29 English in Malaysia: Identity and the Market Place Shirley Geok-lin Lim Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 57 Self-Refashioning a Plural Society: Dialogism and Syncretism in Malaysian Postcolonial Literature Mohammad -

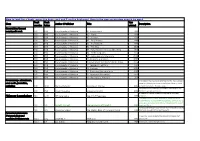

MCG Library Book List Excel 26 04 19 with Worksheets Copy

How to look for a book: press the keys cmd and F on the keyboard, then in the pop up window search by word Book Book Year Class Author / Publisher Title Description number letter printed Generalities/General encyclopedic work 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 01- Environment 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 02 - Plants 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 03 - Animals 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 04 - Early History 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 05 - Architecture 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 06 - The Seas 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 07 - Early Modern History (1800-1940) 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 08 - Performing Arts 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 09 - Languages and Literature 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 10- Religions and Beliefs 2005 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 11-Government and Politics (1940-2006) 2006 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 12- Peoples & Traditions 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 13- Economy 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 14- Crafts and the visual arts 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 15- Sports and Recreation 2008 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 16- The rulers of Malaysia 2011 Documentary-, educational-, In this book Marina draws attention to the many dangers news media, journalism, faced by Malaysia, to concerns to fellow citizens, social publishing 070 MAR Marina Mahathir Dancing on Thin Ice 2015 and political affairs. Double copies. Compilations of he author's thought, reflecting on the 070 RUS Rusdi Mustapha Malaysian Graffiti 2012 World, its people and events. Principles of Tibetan Buddhism applied to everyday Philosopy & psychology 100 LAM HH Dalai Lama The Art of Happiness 1999 problems As Nisbett shows in his book people think about and see the world differently because of differing ecologies, social structures, philosophies and educational systems that date back to ancient 100 NIS Nisbett, Richard The Geography of thought 2003 Greece and China. -

Mahathir's Islam: Mahathir Mohamad on Religion and Modernity In

University of Hawai'i Manoa Kahualike UH Press Book Previews University of Hawai`i Press Fall 10-1-2018 Mahathir’s Islam: Mahathir Mohamad on Religion and Modernity in Malaysia Sven Schottmann Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr Part of the Asian History Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Schottmann, Sven, "Mahathir’s Islam: Mahathir Mohamad on Religion and Modernity in Malaysia" (2018). UH Press Book Previews. 15. https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in UH Press Book Previews by an authorized administrator of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAHATHIR’S ISLAM MAHATHIR’S ISLAM Mahathir Mohamad on Religion and Modernity in Malaysia Sven Schottmann University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2018 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 23 22 21 20 19 18 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Schottmann, Sven, author. Title: Mahathir’s Islam: Mahathir Mohamad on religion and modernity in Malaysia/Sven Schottmann. Description: Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018001939 | ISBN 9780824876470 (cloth ; alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mahathir bin Mohamad, 1925—Religion. | Mahathir bin Mohamad, 1925—Political and social views. | Islam and state—Malaysia. | Malaysia—Politics and government. Classification: LCC DS597.215.M34 S36 2018 | DDC 959.505/4092—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018001939 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70c383r7 Author Syed Abu Bakar, Syed Husni Bin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar August 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Mariam Lam Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar 2015 The Dissertation of Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements There have been many kind souls along the way that helped, suggested, and recommended, taught and guided me along the way. I first embarked on my research on Malay literature, history and Southeast Asian studies not knowing what to focus on, given the enormous corpus of available literature on the region. Two years into my graduate studies, my graduate advisor, a dear friend and conversation partner, an expert on hikayats, Hendrik Maier brought Misa Melayu, one of the lesser read hikayat to my attention, suggesting that I read it, and write about it. If it was not for his recommendation, this dissertation would not have been written, and for that, and countless other reasons, I thank him kindly. I would like to thank the rest of my graduate committee, and fellow Southeast Asianists Mariam Lam and Tamara Ho, whose friendship, advice, support and guidance have been indispensable.