The Theatre of Krishen Jit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Feminist Dialogics Approach in Reading Kee Thuan Chye's Plays

3L: The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies – Vol 22(1): 97 – 109 Reclaiming Voices and Disputing Authority: A Feminist Dialogics Approach in Reading Kee Thuan Chye’s Plays ERDA WATI BAKAR School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia [email protected] NORAINI MD YUSOF School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia RAVICHANDRAN VENGADASAMY School of Language Studies and Linguistics Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia ABSTRACT Kee Thuan Chye in all four of his selected plays has appropriated and reimagined history by giving it a flair of contemporaneity in order to draw a parallel with the current socio-political climate. He is a firm believer of freedom of expression and racial equality. His plays become his didactic tool to express his dismay and frustration towards the folly and malfunctions in the society. He believes that everybody needs to rise and eliminate their fear from speaking their minds regardless of race, status and gender. In all four of his plays, Kee has featured and centralised his female characters by empowering them with voice and agency. Kee gives fair treatment to his women by painting them as strong, liberated, determined and fearless beings. Armed with the literary tools of feminist dialogics which is derived from Bakhtin’s theory of dialogism and strategies of historical re-visioning, this study investigates and explores Kee’s representations of his female characters and the various ways that he has liberated them from being passive and silent beings as they contest the norms, values and even traditions. -

Upin & Ipin: Promoting Malaysian Culture Values Through Animation

Upin & Ipin: Promoting malaysian culture values through animation Dahlan Bin Abdul Ghani Universiti Kuala Lumpur [email protected] Recibido: 20 de enero de 2015 Aceptado: 12 de febrero de 2015 Abstract Malaysian children lately have been exposed or influenced heavily by digital media entertainment. The rise of such entertainment tends to drive them away from understanding and appreciating the values of Malaysian culture. Upin and Ipin animation has successfully promoted Malaysian folklore culture and has significantly portrayed the art of Malaysian values including Islamic values by providing the platform for harmonious relationship among different societies or groups or religious backgrounds. The focus of this research is to look into the usage of Malaysian culture iconic visual styles such as backgrounds, lifestyles, character archetypes and narrative (storytelling). Therefore, we hope that this research will benefit the younger generation by highlighting the meaning and importance of implicit Malaysian culture. Key words: Upin and Ipin; animation; narrative; folklore; culture; character archetypes. Upin e Ipin: promoviendo la cultura malasia a través de los valores de la animación Resumen Recientemente los niños en Malasia están siendo fuertemente expuestos cuando no influenciados por los medios masivos de entretenimiento digital. Esto les lleva una falta de comprensión y apreciación de la importancia de los valores de su propia cultura. La serie de animación propia Upin & Ipin ha promovido con éxito las diferentes culturas de Malasia y obtenido valores culturales significativos que representan a su arte, incluyendo el islámico, y proporcionando así una plataforma de relación armónica entre los diferentes grupos que componen la sociedad en Malasia, ya sea civil o religiosa. -

Text and Screen Representations of Puteri Gunung Ledang

‘The legend you thought you knew’: text and screen representations of Puteri Gunung Ledang Mulaika Hijjas Abstract: This article traces the evolution of narratives about the supernatural woman said to live on Gunung Ledang, from oral folk- View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE lore to sixteenth-century courtly texts to contemporary films. In provided by SOAS Research Online all her instantiations, the figure of Puteri Gunung Ledang can be interpreted in relation to the legitimation of the state, with the folk- lore preserving her most archaic incarnation as a chthonic deity essential to the maintenance of the ruling dynasty. By the time of the Sejarah Melayu and Hikayat Hang Tuah, two of the most impor- tant classical texts of Malay literature, the myth of Puteri Gunung Ledang had been desacralized. Nevertheless, a vestigial sense of her importance to the sultanate of Melaka remains. The first Malaysian film that takes her as its subject, Puteri Gunung Ledang (S. Roomai Noor, 1961), is remarkably faithful to the style and sub- stance of the traditional texts, even as it reworks the political message to suit its own time. The second film, Puteri Gunung Ledang (Saw Teong Hin, 2004), again exemplifies the ideology of its era, depoliticizing the source material even as it purveys Barisan Nasional ideology. Keywords: myth; invention of tradition; Malay literature; Malaysian cinema Author details: Mulaika Hijjas is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fel- low in the Department of South East Asia, SOAS, Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London WC1H 0XG, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. -

The Challenge of Religious Pluralism in Malaysia

The Challenge of Religious Pluralism in Malaysia Mohamed Fauzi Yaacob Introduction HE objective of the paper is to describe a situation in today’s TMalaysia where people of diverse religions are co-existing seeming- ly in relative peace, mutual respect and understanding, but remain insti- tutionally separate, a situation which has been described as religious pluralism. Like many terms in the social sciences, the term “religious pluralism” has been used in many senses by its users. In its widest and most common usage, it has been defined as religious diversity or hetero- geneity, which means a simple recognition of the fact that there are many different religious groups active in any given geo-political space under consideration and that there is a condition of harmonious co-exis- tence between followers of different religions. The term has also been used to mean a form of ecumenism where individuals of different reli- gions dialogue and learn from each other without attempting to convince each other of the correctness of their individual set of beliefs. The third sense in the use of the term is that pluralism means accepting the beliefs taught by religions other than one’s own as valid, but not necessarily true. Its usage in the third sense often gives rise to one controversy or another. For the purpose of this paper, the term religious pluralism is used in the first and second senses, to mean the existence of religious hetero- geneity and attempts at promoting understanding through inter-faith dia- logues. Pluralism in the third sense calls for a totally different approach and methodology which is beyond the ken of the present writer. -

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity

For Justice, Freedom & Solidarity PP3739/12/2010(025927) ISSN 0127 - 5127 RM4.00 2010:Vol.30No.6 Aliran Monthly : Vol.30(6) Page 1 A change is going to come sing my beloved country a change is going to come when the hornbill flies from the white-haired rajah and the dog's head comes to its senses from Kinabalu to the Kinta Valley the monsson flood will cleanse the dirt list, Gilgamesh, to the words of Utnapishtun resore the order of Hammurabi the tainted and the greedy will be swept away and the earth will swallow the rent collectors arise my beloved country a change is going to come when the ghosts of the murdered are finally appeased and we dance on the graves of unjust judges embrace the Kingdom of Heavenly Peace where no one calls himself a lord go forth, Yuanzhang, make bright the light that shines for Umar on his nightly rounds as he seeks out the hungry and cares for the weak while the city sleeps in the lap of justice rejoice my beloved country a change is going to come when the immigrant sheds the skin of the lion and becomes his genuine self again the scales that are gaulty will no more serve to weight out favours in unequal parts give us instead Ashoka's wheel, his welcome to all faiths, his love for all children Martin will see the promised land and the imam will sit down with priest a change is going to come, my beloved country, so sing, arise, rejoice Kee Thuan Chye May 2010 Kuala Lumpur Written specially for Aliran Dinner 26 June 2010 Aliran Monthly : Vol.30(6) Page 2 EDITOR'S NOTE Challenges to press freedom have emerged as oppo- sition parties run into difficulties in renewing per- CONTENTS mits for their party newspapers. -

Cultural Policies to the Creation of Nation-States in the Former Colonies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS THE POLITICS OF DRAMA: POST-1969 STATE POLICIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON THEATRE IN ENGLISH IN MALAYSIA FROM 1970 TO 1999. VELERIE KATHY ROWLAND (B.A. ENG.LIT. (HONS), UNIVERSITY MALAYA) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Theatre practice is largely undocumented in Malaysia. Without the many practitioners who gave of their time, and their valuable theatre programme collections, my efforts to piece together a chronology of theatre productions would not have been possible. Those whose contribution greatly assisted in my research include Ivy Josiah, Chin San Sooi, Thor Kah Hoong, Datuk Noordin Hassan, Datuk Syed Alwi, Marion D’Cruz, Shanti Ryan, Mano Maniam, Mervyn Peters, Susan Menon, Noorsiah Sabri, Sabera Shaik, Faridah Merican, Huzir Sulaiman, Jit Murad, Kee Thuan Chye, Najib Nor, Normah Nordin, Rosmina Tahir, Zahim Albakri and Vijaya Samarawickram. I received tremendous support from Krishen Jit, whose probing intellectualism coupled with a historian’s insights into theatre practice, greatly benefited this work. The advice, feedback and friendship of Jo Kukathas, Wong Hoy Cheong, Dr. Sumit Mandal, Dr. Tim Harper, Jenny Daneels, Rahel Joseph, Adeline Tan and Eddin Khoo are also gratefully acknowledged. The three years spent researching this work would not have been possible without the research scholarship awarded by the National University of Singapore. For this I wish to thank Dr. Ruth Bereson, for her support and advice during the initial stages of application. I also wish to thank Prof. -

Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings

Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA: PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS EDISI KEDUA TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA: PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS EDISI KEDUA Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Kuala Lumpur 2020 © Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 2020 Hak cipta terpelihara. Tiada bahagian terbitan ini boleh diterbitkan semula atau ditukar dalam apa jua bentuk dan dengan apa jua sama ada elektronik, mekanikal, fotokopi, rakaman dan sebagainya sebelum mendapat kebenaran bertulis daripada Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. Diterbitkan oleh: Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia 232, Jalan Tun Razak 50572 Kuala Lumpur Tel: 03-2687 1700 Faks: 03-2694 2490 www.pnm.gov.my www.facebook.com/PerpustakaanNegaraMalaysia blogpnm.pnm.gov.my twitter.com/PNM_sosial Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Data Pengkatalogan-dalam-Penerbitan TAJUK PERKARA MALAYSIA : PERLUASAN LIBRARY OF CONGRESS SUBJECT HEADINGS. – EDISI KEDUA. Mode of access: Internet eISBN 978-967-931-359-8 1. Subject headings--Malaysia. 2. Subject headings, Malay. 3. Government publications--Malaysia. 4. Electronic books. I. Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia. 025.47 KANDUNGAN Sekapur Sirih Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia i Prakata Pengenalan ii Objektif iii Format iv-v Skop vi-viii Senarai Ahli Jawatankuasa Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings ix Senarai Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Tajuk Perkara Topikal (Tag 650) 1-152 Tajuk Perkara Geografik (Tag 651) 153-181 Bibliografi 183-188 Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Sekapur Sirih Ketua Pengarah Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Syukur Alhamdulillah dipanjatkan dengan penuh kesyukuran kerana dengan izin- Nya Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia telah berjaya menerbitkan buku Tajuk Perkara Malaysia: Perluasan Library of Congress Subject Headings Edisi Kedua ini. -

Report of the Official Parliamentary Delegation to Sri Lanka and Malaysia

THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Report of the Australian Parliamentary Delegation to Malaysia and to Sri Lanka 5 December to 14 December 2011 October 2012 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia Report of the Australian Parliamentary Delegation Malaysia and Sri Lanka 5 December to 14 December 2011 October 2012 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 ISBN 978-0-642-79614-1 (Printed version) This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Australia License. The details of this licence are available on the Creative Commons website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. Contents Membership of the Delegation ................................................................................. vi REPORT 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 1 Aims and objectives of the visits ................................................................................................. 2 Appreciation ................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Malaysia ............................................................................................................... 5 Malaysia at a glance ................................................................................................................... 5 Background .............................................................................................................................. -

UNSUR-UNSUR MISTIK DAN PEMUJAAN DALAM KALANGAN MASYARAKAT MELAYU DI PULAU BESAR NEGERI MELAKA SYAIMAK ISMAIL Universiti Teknologi Mara [email protected]

Jurnal Melayu Bil. 19(2)2020 254 UNSUR-UNSUR MISTIK DAN PEMUJAAN DALAM KALANGAN MASYARAKAT MELAYU DI PULAU BESAR NEGERI MELAKA SYAIMAK ISMAIL Universiti Teknologi Mara [email protected] MUHAMMAD SAIFUL ISLAM ISMAIL Universiti Teknologi Mara [email protected] ABSTRAK Pulau Besar merupakan pulau yang berpenghuni yang terletak di negeri Melaka. Pulau ini mula wujud sejak daripada zaman Kesultanan Melayu Melaka dan banyak peristiwa sejarah yang berlaku di pulau ini. Kehadiran ulama tersohor ke Pulau Besar sekitar abad ke-15 untuk menyebarkan agama Islam dianggap sebagai wali Allah dilihat wajar dihormati dan dipuja kerana kedudukannya yang tinggi di sisi tuhan. Peninggalan makam ulama beserta pengikut beliau dikatakan mewarnai Pulau Besar dengan hal-hal positif kerana memberikan seribu kebaikan kepada penduduk dan pengunjung yang datang ke pulau ini. Oleh demikian, Pulau Besar dianggap sebagai sebuah pulau yang suci dan keramat kerana mampu menyembuhkan penyakit, menyucikan hati dan menunaikan hajat setiap pengunjung yang datang ke pulau ini. Kebiasaannya masyarakat Melayu khususnya di Melaka akan mengunjungi beberapa tempat yang dianggap suci yang terdapat di pulau ini seperti kubur, gua, pokok dan batu besar untuk berdoa, memohon hajat, menunaikan nazar dan majalani sesi rawatan secara ghaib di Pulau Besar. Kesan daripada pengaruh fahaman animisme dan Hindu-Buddha yang diterima secara warisan daripada leluhur terdahulu masih lagi menjadi amalan sejak berzaman. Walaubagaimanapun, masyarakat Melayu mula menyesuaikan amalan tersebut mengikut kesesuaian agama Islam sebaik sahaja agama ini diperkenalkan di alam Melayu. Objektif kajian ini bertujuan untuk mengenalpasti unsur-unsur mistik dan pemujaan dalam kalangan masyarakat Melayu di Pulau Besar. Kajian ini menggunakan metod dokumentasi dan observasi bagi melihat secara menyeluruh bentuk amalan dan pemujaan yang masih dilakukan oleh masyarakat Melayu yang mengunjungi Pulau Besar ini. -

Malaysian Literature in English

Malaysian Literature in English Malaysian Literature in English: A Critical Companion Edited by Mohammad A. Quayum Malaysian Literature in English: A Critical Companion Edited by Mohammad A. Quayum This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Mohammad A. Quayum and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-4929-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-4929-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ 1 Mohammad A. Quayum Chapter One .............................................................................................. 12 Canons and Questions of Value in Literature in English from the Malayan Peninsula Rajeev S. Patke Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 29 English in Malaysia: Identity and the Market Place Shirley Geok-lin Lim Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 57 Self-Refashioning a Plural Society: Dialogism and Syncretism in Malaysian Postcolonial Literature Mohammad -

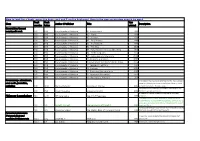

MCG Library Book List Excel 26 04 19 with Worksheets Copy

How to look for a book: press the keys cmd and F on the keyboard, then in the pop up window search by word Book Book Year Class Author / Publisher Title Description number letter printed Generalities/General encyclopedic work 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 01- Environment 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 02 - Plants 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 03 - Animals 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 04 - Early History 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 05 - Architecture 1998 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 06 - The Seas 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 07 - Early Modern History (1800-1940) 2001 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 08 - Performing Arts 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 09 - Languages and Literature 2004 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 10- Religions and Beliefs 2005 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 11-Government and Politics (1940-2006) 2006 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 12- Peoples & Traditions 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 13- Economy 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 14- Crafts and the visual arts 2007 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 15- Sports and Recreation 2008 030 ENC Encyclopedia of Malaysia 16- The rulers of Malaysia 2011 Documentary-, educational-, In this book Marina draws attention to the many dangers news media, journalism, faced by Malaysia, to concerns to fellow citizens, social publishing 070 MAR Marina Mahathir Dancing on Thin Ice 2015 and political affairs. Double copies. Compilations of he author's thought, reflecting on the 070 RUS Rusdi Mustapha Malaysian Graffiti 2012 World, its people and events. Principles of Tibetan Buddhism applied to everyday Philosopy & psychology 100 LAM HH Dalai Lama The Art of Happiness 1999 problems As Nisbett shows in his book people think about and see the world differently because of differing ecologies, social structures, philosophies and educational systems that date back to ancient 100 NIS Nisbett, Richard The Geography of thought 2003 Greece and China. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/70c383r7 Author Syed Abu Bakar, Syed Husni Bin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Playing Along Infinite Rivers: Alternative Readings of a Malay State A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar August 2015 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Mariam Lam Dr. Tamara Ho Copyright by Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar 2015 The Dissertation of Syed Husni Bin Syed Abu Bakar is approved: ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements There have been many kind souls along the way that helped, suggested, and recommended, taught and guided me along the way. I first embarked on my research on Malay literature, history and Southeast Asian studies not knowing what to focus on, given the enormous corpus of available literature on the region. Two years into my graduate studies, my graduate advisor, a dear friend and conversation partner, an expert on hikayats, Hendrik Maier brought Misa Melayu, one of the lesser read hikayat to my attention, suggesting that I read it, and write about it. If it was not for his recommendation, this dissertation would not have been written, and for that, and countless other reasons, I thank him kindly. I would like to thank the rest of my graduate committee, and fellow Southeast Asianists Mariam Lam and Tamara Ho, whose friendship, advice, support and guidance have been indispensable.