Satirical Narrative in Early Irish Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish Narrative Literature with Particular Reference to Tales Belonging to the Ulster Cycle

The role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish narrative literature with particular reference to tales belonging to the Ulster Cycle. Mary Leenane, B.A. 2 Volumes Vol. 1 Ph.D. Degree NUI Maynooth School of Celtic Studies Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies and Philosophy Head of School: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Supervisor: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn June 2014 Table of Contents Volume 1 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I: General Introduction…………………………………………………2 I.1. Ulster Cycle material………………………………………………………...…2 I.2. Modern scholarship…………………………………………………………...11 I.3. Methodologies………………………………………………………………...14 I.4. International heroic biography………………………………………………..17 Chapter II: Sources……………………………………………………………...23 II.1. Category A: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a significant role…………...23 II.2. Category B: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a more limited role………...41 II.3. Category C: Texts in which Cú Chulainn makes a very minor appearance or where reference is made to him…………………………………………………...45 II.4. Category D: The tales in which Cú Chulainn does not feature………………50 Chapter III: Cú Chulainn’s heroic biography…………………………………53 III.1. Cú Chulainn’s conception and birth………………………………………...54 III.1.1. De Vries’ schema………………...……………………………………………………54 III.1.2. Relevant research to date…………………………………………………………...…55 III.1.3. Discussion and analysis…………………………………………………………...…..58 III.2. Cú Chulainn’s youth………………………………………………………...68 III.2.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………68 III.2.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………69 III.2.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..78 III.3. Cú Chulainn’s wins a maiden……………………………………………….90 III.3.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………90 III.3.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………91 III.3.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..95 III.3.4 Further comment……………………………………………………………………...108 III.4. -

The Death-Tales of the Ulster Heroes

ffVJU*S )UjfáZt ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV KUNO MEYER, Ph.D. THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO. LTD. LONDON: WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 (Reprinted 1937) cJ&íc+u. Ity* rs** "** ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV. KUNO MEYER THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO., Ltd, LONDON : WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 °* s^ B ^N Made and Printed by the Replika Process in Great Britain by PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES &f CO. LTD. 1 2 Bedford Square, London, W.C. i and at Bradford CONTENTS PAGE Peeface, ....... v-vii I. The Death of Conchobar, 2 II. The Death of Lóegaire Búadach . 22 III. The Death of Celtchar mac Uthechaib, 24 IV. The Death of Fergus mac Róich, . 32 V. The Death of Cet mac Magach, 36 Notes, ........ 48 Index Nominum, . ... 46 Index Locorum, . 47 Glossary, ....... 48 PREFACE It is a remarkable accident that, except in one instance, so very- few copies of the death-tales of the chief warriors attached to King Conchobar's court at Emain Macha should have come down to us. Indeed, if it were not for one comparatively late manu- script now preserved outside Ireland, in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh, we should have to rely for our knowledge of most of these stories almost entirely on Keating's History of Ireland. Under these circumstances it has seemed to me that I could hardly render a better service to Irish studies than to preserve these stories, by transcribing and publishing them, from the accidents and the natural decay to which they are exposed as long as they exist in a single manuscript copy only. -

Meet the Fáilte Ireland Team

MEET THE FÁILTE IRELAND TEAM An easy guide to who you can contact in Fáilte Ireland Dublin The Dublin programme is responsible for the promotion and development of Dublin’s tourism industry. Four visitor experience themes have been identified and, through these and the new Dublin brand, we will bring to life the Dublin proposition which is ‘a vibrant capital city bursting with a variety of surprising experiences – where city living thrives side by side with natural outdoors’. Keelin Fagan, Head of Dublin, Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens Street, Dublin 1 Key contacts: T: 01 8847200 M: 086 0493083 E: [email protected] BUSINESS AREA NAME CONTACT DETAILS Programme Manager Mark Rowlette Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens St Dublin 1, D01 WR86 T: 01 8847132 M: 087 2342869 E: [email protected] Programme Manager Helen McDaid Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens St Dublin 1, D01 WR86 T: 01 8847170 M: 086 8034912 E: [email protected] Programme Officer – Daire Enright Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens St Dublin 1, D01 WR86 Extraordinary Days T: 01 8847894 and Happening Nights E: [email protected] Programme Officer – Marion O’Connor Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens St Dublin 1, D01 WR86 Dublin Stories – T: 01 8847894 Hidden and Untold E: [email protected] Programme Officer – Catherine McCluskey Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens St Dublin 1, D01 WR86 City of Words T: 01 8847268 M: 086 7749876 E: [email protected] Programme Officer – Ciara Scully Áras Fáilte, 88-95 Amiens St Dublin 1, D01 WR86 Living Bay T: 01 8847261 M: 086 8553388 E: [email protected] Wild Atlantic Way The Wild Atlantic Way, the longest defined coastal touring route in the world stretching 2,500km from Inishowen in Donegal to Kinsale in West Cork, leads you through one of the world’s most dramatic landscapes. -

Definitive Version Thesis Kruithof FAYE.Pdf

War is (not) a board-game The function of medieval Irish board games and their players Bachelor’s thesis Kruithof, F.A.Y.E. Word count: 8188 16-10-2018 Supervisor: Petrovskaia, N. Celtic Languages and Culture Utrecht University List of content Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 2 List of abbreviations .................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Previous research.................................................................................................................... 5 Theoretical framework ........................................................................................................... 7 Approach and sources ............................................................................................................ 9 Chapter One: Players in the Ulster Cycle: Opponents ............................................................. 11 Eochaid Airem and Midir of Brí Leith ................................................................................. 11 Manannán mac Lir and Fand ................................................................................................ 12 Cú Chulainn and Láeg mac Riangabra ................................................................................. 13 Conchobar, -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung As a Junction Within Lebor Gabála Érenn

Edinburgh Research Explorer Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn Citation for published version: Thanisch, E 2013, Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn. in Quaestio Insularis: Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon Norse and Celtic. vol. 13, pp. 69-93. <http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/publications/quaestio/Quaestio2012.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaestio Insularis General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor 1 Gabála Érenn INTRODUCTION Lebor Gabála Érenn: Content Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘the Book of the Invasion of Ireland’) is the conventional title for a lengthy Irish pseudo-historical text extant in multiple recensions probably compiled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 The text comprises a history of the Gaídil (‘Gaels’) within the context of a universal history derived from the Bible and from Classical historiography.3 Lebor Gabála traces the ancestry of the Gaídil back to Noah and follows their tortuous migrations, spanning many generations, from the Tower of Babel to Ireland via Spain. -

Heroic Romances of Ireland Volume 1

Heroic Romances of Ireland Volume 1 A. H. Leahy Heroic Romances of Ireland Volume 1 Table of Contents Heroic Romances of Ireland Volume 1,..................................................................................................................1 A. H. Leahy....................................................................................................................................................1 HEROIC ROMANCES OF IRELAND.........................................................................................................2 A. H. LEAHY................................................................................................................................................2 IN TWO VOLUMES.....................................................................................................................................2 VOL. I............................................................................................................................................................2 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION IN VERSE.......................................................................................................................9 PRONUNCIATION OF PROPER NAMES................................................................................................12 LIST OF NAMES........................................................................................................................................12 -

Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: a True Exponent of the Bardic Legacy

134 Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: A True Exponent of the Bardic Legacy endowed university. The Bardic schools and the monastic schools were the universities of their day; they bestowed privileges and Barra Ó Donnabháin Symposium: status on their students and teachers, much as the modern university awards degrees and titles to recipients to practice certain professions. There are few descriptions of the structure and operation of Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: A the Bardic schools, but an account contained in the early eighteenth century Memoirs of the Marquis of Clanricarde claims that admission True Exponent of the Bardic WR %DUGLF VFKRROV ZDV FRQÀQHG WR WKRVH ZKR ZHUH GHVFHQGHG from poets and had within their tribe “The Reputation” for poetic Legacy OHDUQLQJ DQG WDOHQW ´7KH TXDOLÀFDWLRQV ÀUVW UHTXLUHG VLF ZHUH Pádraig Ó Cearúill reading well, writing the Mother-tongue, and a strong memory,” according to Clanricarde. With regard to the location of the schools, he asserts that it was necessary that the place should “be in the solitary access of a garden” or “within a set or enclosure far out of the reach of any noise.” The structure containing the Bardic school, we are told, “was snug, low, hot and beds in it at convenient distances, each within a small apartment without much furniture of any kind, save only a table, some seats and a conveniency for he poetry of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin (1748-1784)— cloaths (sic) to hang upon. No windows to let in the day, nor any Tregarded as one of Ireland’s great eighteenth century light at all used but that of candles” according to Clanricarde,2 poets—has endured because of it’s extraordinary metrical whose account is given credence by Bergin3 and Corkery. -

YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares Beside the Edmund Dulac Memorial Stone to W

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/194 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the same series YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 1, 2 Edited by Richard J. Finneran YEATS ANNUALS Nos. 3-8, 10-11, 13 Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS AND WOMEN: YEATS ANNUAL No. 9: A Special Number Edited by Deirdre Toomey THAT ACCUSING EYE: YEATS AND HIS IRISH READERS YEATS ANNUAL No. 12: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould and Edna Longley YEATS AND THE NINETIES YEATS ANNUAL No. 14: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS’S COLLABORATIONS YEATS ANNUAL No. 15: A Special Number Edited by Wayne K. Chapman and Warwick Gould POEMS AND CONTEXTS YEATS ANNUAL No. 16: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould INFLUENCE AND CONFLUENCE: YEATS ANNUAL No. 17: A Special Number Edited by Warwick Gould YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 Frontispiece: Derry Jeffares beside the Edmund Dulac memorial stone to W. B. Yeats. Roquebrune Cemetery, France, 1986. Private Collection. THE LIVING STREAM ESSAYS IN MEMORY OF A. NORMAN JEFFARES YEATS ANNUAL No. 18 A Special Issue Edited by Warwick Gould http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2013 Gould, et al. (contributors retain copyright of their work). The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text. -

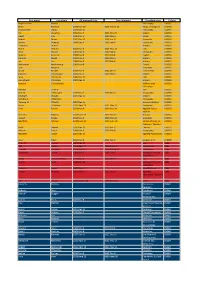

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark.