Missing Bodies and the Practice of Recovery A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High School Profile 20-21

Physical Address : 11 Calle 15‐79, Zona 15, Vista Hermosa III, Guatemala 01015 Mailing Address : 7801 NW 37th St, Section 1783, Miami, Florida 33166‐6559 School Code: 854200 www.cag.edu.gt 2020-2021 School Profile Vision: A legacy of meaningful lives that brings value to Guatemalan and global communities. Mission: The mission of the American School of Guatemala is to empower its students to achieve their full potential and to inspire them to lead meaningful lives as responsible members of a global society. Learner Profile VIDAS: CAG learners are empowered to achieve their full potential and live meaningful lives that bring value to Guatemalan and global communities as thinkers, communicators, and leaders who are: Values-Oriented, Innovative, Dynamic, Actively engaged, and Service-driven. High School Elective Course Options: 4% 6% 8% Enrollment: 82% Guatemalan 454 +1630 24 8% United States High school students Pre‐school through Nationalities 4% Korean 82% 104 seniors and 29 YSA program grade 12 students represented students 6% Other countries Faculty: Class Size: Accreditation: Governance: Appointed Board of Membership: Directors, sponsored by American Association of Schools in Central the Foundation of the America University del Valle de Association of American Schools in South America Guatemala Association for the Advancement of International Education New England Association Tri-Regional Association of American Schools in 52 19 of Colleges and Schools Central America, Mexico, Colombia and the Caribbean High School educators Students per class (NEASC) Founded: 1945 National Association of Independent Schools High School Extracurricular Offerings: Academic Program: 20% The high school curriculum is that of a U.S. -

Civil War and Daily Life: Snapshots of the Early War in Guatemala - Not Even Past

Civil War and Daily Life: Snapshots of the Early War in Guatemala - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 16 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Civil War and Daily Life: Snapshots of the Early War in Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Guatemala Confederacy” May 06, 2020 More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books DIGITAL HISTORY by Vasken Markarian Más de 72: Digital Archive Review https://notevenpast.org/civil-war-and-daily-life-snapshots-of-the-early-war-in-guatemala/[6/22/2020 12:21:40 PM] Civil War and Daily Life: Snapshots of the Early War in Guatemala - Not Even Past (All photos here are published with the permission of the photographer.) Two young Guatemalan soldiers abruptly pose for the camera. They rush to stand upright with rifles at their sides. On a dirt road overlooking an ominous Guatemala City, they stand on guard duty. This snapshot formed the title page of an exhibit at the University of Texas at Austin’s Benson Latin American Collection in 2018. A collection of these and other documents by Rupert Chambers will become part of a permanent archive at the library. The photographs depict the year 1966, a time of martial law and March 16, 2020 increasing state repression of leftist movements and supporters of reform. -

Ethnology: West Indies

122 / Handbook of Latin American Studies traditional hierarchies. Ties to the municipal market, small amounts of valley-grown maize center are loosened when hamlets build their and vegetables are exchanged for hiU prod own chapels. The associated rituals and ucts such as fruit. Many vendors prefer barter offices emphasize cooperation rather than le to cash sales, and the author concludes that gitimizing hierarchical status. Whether these the system is efficient. changes have been made in an attempt to 990 Young, James C.-Illness categories restrain inequalities created by moderniza and action strategies in a Tarascan town tion, as the author suggests, or to release (AAA/AE, 5; I, Feb. 1978, p. 81-97, Wbl., il- funds once enciunbered in rehgious ritual for lus., tables) capitalist operations, is an open question. In Pichátaro, Michoacán, Mex., formal 987 -------- . Land and labor in central eliciting procedines yielded 34 terms for ill Chiapas; a regional analysis (SP/DC, ness and 43 attributes. Hierarchical clustering 8:4, Oct. t977, p. 44t-4Ö3, bibl., map, tables) techniques then produced an organization of After surveying the development of the data that is roughly analogous to the tax commercial agriculture in Chiapas after iSzr, onomies of ethnosemantics. The underlying the author compares the differing ways that distinctions that appear to orgmize the data tenant farmers from’Zinacantan and day la are internal locus bf cause, seriousness, and borers from Chamula have been incorporated life-stage of the victim. Although the "hot- into the commercial sector. An analysis of cold" distinction is important in treatment, it class relations and confhcting interests is con is not so pervasive in the system as other trasted to Aguirre Beltrán's (see item 879) research in Mexico has suggested. -

Amnesty International, Human Rights & U.S. Policy

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL, HUMAN RIGHTS & U.S. POLICY Maria Baldwin A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Committee: Gary R. Hess, Advisor Franklin W. Goza Graduate Faculty Representative Robert Buffington Douglas Forsyth ii ABSTRACT Gary R. Hess, Advisor This dissertation assesses Amnesty International’s ability to influence U.S. foreign policy through an examination of its human rights campaigns in three different nations—Guatemala, the United States and the People’s Republic of China. While these nations are quite different from one another, according to Amnesty International they share an important characteristic; each nation has violated their citizens’ human rights. Sometimes the human rights violations, which provoked Amnesty International’s involvement occurred on a large scale; such as the “disappearances” connected with Guatemala’s long civil war or the imprisonment of political dissidents in the PRC. Other times the human rights violations that spurred Amnesty International’s involvement occurred on a smaller-scale but still undermined the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; such as the United States use of capital punishment. During the Guatemalan and Chinese campaigns Amnesty International attempted to influence the United States relations with these countries by pressuring U.S. policymakers to construct foreign policies that reflected a grave concern for institutionalized human rights abuse and demanded its end. Similarly during its campaign against the United States use of the death penalty Amnesty International attempted to make it a foreign policy liability for the United States. How effective Amnesty International has been in achieving these goals is the subject of this dissertation. -

Social Exclusion and the Negotiation of Afro-Mexican Identity in the Costa Chica of Oaxaca, Mexico

Social Exclusion and the Negotiation of Afro-Mexican Identity in the Costa Chica of Oaxaca, Mexico. Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg i. Br. vorgelegt von Tristano Volpato aus Verona, Italien WS 2013/2014 Erstgutachter: Prof. Hermann Schwengel Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Julia Flores Dávila Vorsitzender des Promotionsausschusses der Gemeinsamen Kommission der Philologischen, Philosophischen und Wirtschafts- und Verhaltenswissenschaftlichen Fakultät: Prof. Dr. Bernd Kortmann Datum der Fachprüfung im Promotionsfach: 07 Juli 2014 Social Exclusion and the Negotiation of Afro-Mexican Identity in the Costa Chica of Oaxaca, Mexico. Tristano Volpato Nr.3007198 [email protected] II I acknowledge Prof. Schwengel, for the opportunity to make concrete an important proyect for my professional life and individual psychological growing, since he was in constant cooperation with me and the work; Prof. Julia Flores Dávila, who accompanied me during the last six years, with her human and professional presence; my parents, who always trusted me; Gisela Schenk, who was nearby me in every occasion, professonal and daily. Finally I want to specially thank all those people of the Costa Chica who, during the process, allowed me to understand better their identity and offered a great example of Mexicanity and humanity. III IV Contents Prefacio ............................................................................................................................ -

The Force of Re-Enslavement and the Law of “Slavery” Under the Regime of Jean-Louis Ferrand in Santo Domingo, 1804-1809

New West Indian Guide Vol. 86, no. 1-2 (2012), pp. 5-28 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/nwig/index URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101725 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0028-9930 GRAHAM NESSLER “THE SHAME OF THE NATION”: THE FORCE OF RE-ENSLAVEMENT AND THE LAW OF “SLAVERy” UNDER THE REGIME OF JEAN-LOUIS FERRAND IN SANTO DOMINGO, 1804-1809 On October 10, 1802, the French General François Kerverseau composed a frantic “proclamation” that detailed the plight of “several black and colored children” from the French ship Le Berceau who “had been disembarked” in Santo Domingo (modern Dominican Republic).1 According to the “alarms” and “foolish speculations” of various rumor-mongers in that colony, these children had been sold into slavery with the complicity of Kerverseau.2 As Napoleon’s chief representative in Santo Domingo, Kerverseau strove to dis- pel the “sinister noises” and “Vain fears” that had implicated him in such atrocities, insisting that “no sale [of these people] has been authorized” and that any future sale of this nature would result in the swift replacement of any “public officer” who authorized it. Kerverseau concluded by imploring his fellow “Citizens” to “distrust those who incessantly spread” these rumors and instead to “trust those who are charged with your safety; who guard over 1. In this era the term “Santo Domingo” referred to both the Spanish colony that later became the Dominican Republic and to this colony’s capital city which still bears this name. In this article I will use this term to refer only to the entire colony unless otherwise indicated. -

Art Alfombra Holy Week Program Antigua, Guatemala Student Handbook 2017 - 2018

Art Alfombra Holy Week Program Antigua, Guatemala Student Handbook 2017 - 2018 Casa Herrera Staff and Emergency Contacts Milady Casco On-Site Coordinator Casa Herrera Cell: 011-502-5704-1338 Office: 011-502-7832-0760 Dr. Astrid Runggaldier Assistant Director The Mesoamerica Center Cell: 617-780-7826 Office: 512-471-6292 Table of Contents ABOUT CASA HERRERA ............................................................................................................ 1 PURPOSE .......................................................................................................................................1 FACILITIES OVERVIEW.......................................................................................................................1 FACULTY/STAFF ..............................................................................................................................2 LENT AND HOLY WEEK ............................................................................................................. 5 WHAT ARE LENT AND HOLY WEEK?....................................................................................................5 WHAT IS HOLY WEEK LIKE IN ANTIGUA GUATEMALA? ...........................................................................7 IMPORTANT TERMS, ACTIVITIES, AND MOMENTS OF HOLY WEEK ............................................................7 HELPFUL TIPS FOR HOLY WEEK IN ANTIGUA.........................................................................................9 LIFESTYLE AND CULTURE ...................................................................................................... -

Demands for Economic and Environmental Justice

Farmers shout anti-government slogans on a blocked highway during a protest against new farm laws in December 2020 in Delhi, India. Photo by Yawar Nazir/Getty Images 2021 State of Civil Society Report DEMANDS FOR ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE Economic and environmental climate mobilisations↗ that marked 2019 and that pushed climate action to the top of the political agenda. But people continued to keep up the momentum justice: protest in a pandemic year by protesting whenever and however they could, using their imaginations In a year dominated by the pandemic, people still protested however and offering a range of creative actions, including distanced, solo and online and whenever possible, because the urgency of the issues continued protests. State support to climate-harming industries during the pandemic and to make protest necessary. Many of the year’s protests came as people plans for post-pandemic recovery that seemed to place faith in carbon-fuelled responded to the impacts of emergency measures on their ability to economic growth further motivated people to take urgent action. meet their essential needs. In country after country, the many people left living precariously and in poverty by the pandemic’s impacts on Wherever there was protest there was backlash. The tactics of repression were economic activity demanded better support from their governments. predictably familiar and similar: security force violence against protesters, Often the pandemic was the context, but it was not the whole story. For arrests, detentions and criminalisation, political vilification of those taking some, economic downturn forced a reckoning with deeply flawed economic part, and attempts to repress expression both online and offline. -

January 2006

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE JANUARY 2006 StateStateMAGAZINE WWalkalk thethe WWALKALK Embassy Information Management Officer Dan Siebert, center, set up this computer lab. He and other Americans volunteer their time to help Lesotho move forward. IN OUR NEXT ISSUE: Lesotho–Kingdom in the Sky State Magazine (ISSN 1099–4165) is published monthly, except bimonthly in July and August, by the U.S. Department of State, 2201 C St., N.W., Washington, DC. Periodicals postage State paid at Washington, D.C., and at additional mailing locations. MAGAZINE Send changes of address to State Magazine,HR/ER/SMG, SA-1, Rob Wiley Room H-236, Washington, DC 20522-0108. You may also EDITOR-IN-CHIEF e-mail address changes to [email protected]. Bill Palmer State Magazine is published to facilitate communication WRITER/EDITOR between management and employees at home and abroad and Jennifer Leland to acquaint employees with developments that may affect oper- WRITER/EDITOR ations or personnel. The magazine is also available to persons interested in working for the Department of State and to the David L. Johnston general public. ART DIRECTOR State Magazine is available by subscription through the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS Office, Washington, DC 20402 (telephone [202] 512-1800) or on the web at http://bookstore.gpo.gov. Teddy B. Taylor For details on submitting articles to State Magazine,request EXECUTIVE SECRETARY our guidelines, “Getting Your Story Told,” by e-mail at Larry Baer [email protected]; download them from our web site at Kelly Clements www.state.gov;or send your request in writing to State Magazine,HR/ER/SMG, SA-1, Room H-236, Washington, DC Pam Holliday 20522-0108. -

Social Sector Investment Programme 2020

SOCIAL SECTOR 2020 INVESTMENT PROGRAMME CONTENTS Executive Summary 8 Introduction 20 CHAPTER 1: THE INTERNATIONAL SITUATION 24 1.1. Socio-Economic Outlook 24 1.1.1. Global Competitiveness 25 1.1.2. Global Gender Gap 25 1.1.3. Human Development 26 1.1.4. Poverty 26 1.1.5. Health and Wellness 27 1.1.6. The Environment 28 1.1.7. Corruption 28 CHAPTER 2: THE CARIBBEAN SOCIAL SITUATION 32 2.1. Regional Economic Development 32 2.1.1. Economy 32 2.2. Regional Integration 33 2.2.1. CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) 33 2.3. Regional Social Development 33 2.3.1. Human Capital Development 33 2.3.2. Social Security 34 2.3.3. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 34 2.3.4. Poverty (Reduction) in the Region 35 2.3.5. Employment 35 2.3.6. An Ageing Caribbean 35 2.3.7. Crime and Security 36 2.3.8. Migration 36 2.3.9. Gender Mainstreaming 37 2.3.10. Health Care 37 2.3.11. Disabilities 39 2.3.12. Disaster Management – Environmental Stability 39 2.3.13. Literacy in the Caribbean & Education 40 2.3.14. Food Security 40 2.3.15. Maritime Industry 40 2.4. Regional Dialogue 41 2.5. Outlook for 2020 41 2 STABILITY | STRENGTH | GROWTH CHAPTER 3: TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO IN THE CONTEXT OF THE CARIBBEAN 44 3.1. Global Gender Gap 44 3.2. World Happiness 45 3.3. Global Peace Index 45 3.4. Corruption 45 CHAPTER 4: THE NATIONAL SOCIAL SITUATION 48 4.1. -

Geology and Geothermal Potential of the Tecuamburro Volcano Area Of

Geothermics, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 425-446, 1992. 0375~505/92 $5.00 + 0.00 Printed in Great Britain. Pergamon Press Ltd CNR. GEOLOGY AND GEOTHERMAL POTENTIAL OF THE TECUAMBURRO VOLCANO AREA, GUATEMALA W. A. DUFFIELD,* G. H. HEIKEN,+ K. H. WOHLETZ,i L. W. MAASSEN,+ G. DENGO,~ E. H. MCKEE§ and OSCAR CASTAIqEDA H :~ U.S. Geological Surw'y, 2255 North Gemini, Flagstaff, AZ 80001, U.S.A ; ", Los Alamos National Laboratory. Earth and Environmental Sciences l )ivision, Los Alamo,s, NM 87545, U.S.A. : -(,'entro de Estudios Geologicos de America Central, Apartado 468, Guatemala City, Guatemala; § U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025, U.S.A. : and ]]lnstituto National de Electr([icacion, Guatemala City, Guatemala. (Received June 1991 : accepted,fbr publication May 1992 ) Abstraet--Tecuamburro, an andesitic stratovolcano in southeastern Guatemala, is within the chain of active volcanoes of Central America. Though Tecuamburro has no record of historic eruptions, radiocarbon ages indicate that eruption of this and three other adjacent volcanoes occurred within the past 38,300 years. The youngest eruption produced a dacite dome. Moreover, powerful steam explosions formed a 250 m wide crater about 2900 years ago near the base of this dome, The phreatic crater contains a pH-3 thermal lake. Fumaroles are common along the lake shore, and several other fumaroles are located nearby. Neutral-chloride hot springs are at lower elevations a few kilometers away. All thermal manifestations are within an area of about 400 km2 roughly centered on Tecuamburro Volcano. Thermal implications of the volume, age, and composition of the post-38.3 ka volcanic rocks suggest that magma, or recently solidified hot plutons, or both are in the crust beneath these lavas. -

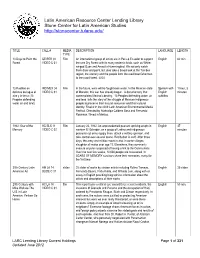

Latin American Resource Center Lending Library Stone Center for Latin American Studies

Latin American Resource Center Lending Library Stone Center for Latin American Studies http://stonecenter.tulane.edu/ TITLE CALL # MEDIA DESCRIPTION LANGUAGE LENGTH TYPE 10 Days to Paint the GE PER 02 Film An international group of artists are in Peru & Ecuador to support English 82 min Forest VIDEO C 01 the rare Dry Forest with its many endemic birds, such as White- winged Guan and Amazilia Hummingbird. We not only watch them draw and paint, but also take a broad look at the Tumbes region, the scenery and the people from the reed boat fishermen to the cloud forest. 2004 13 Pueblos en IND MEX 04 Film In the future, wars will be fought over water. In the Mexican state Spanish with 1 hour, 3 defensa del agua el VIDEO C 01 of Morelos, this war has already begun. A documentary that English minutes aire y la tierra (13 contemplates Mexico’s destiny, 13 Peoples defending water, air subtitles Peoples defending and land tells the story of the struggle of Mexican indigenous water air and land) people to preserve their natural resources and their cultural identity. Finalist in the 2009 Latin American Environmental Media Festival. Directed by Atahualpa Caldera Sosa and Fernanda Robinson. filmed in Mexico. 1932: Scar of the HC ELS 11 Film January 22, 1932. An unprecedented peasant uprising erupts in English 47 Memory VIDEO C 02 western El Salvador, as a group of Ladino and indigenous minutes peasants cut army supply lines, attack a military garrison, and take control over several towns. Retribution is swift. After three days, the army and militias move in and, in some villages, slaughter all males over age 12.