2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 8(10), 624-632

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies: What’S Shakespeare to Them, Or They to Shakespeare

Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies: What’s Shakespeare To Them, or They to Shakespeare Shakespeare Association of America Annual Meeting 2021 2 April 2021, 8-11am EDT About the Seminar Co-leader: Amrita Dhar (Ohio State University) Co-leader: Amrita Sen (University of Calcutta) Seminar keywords: vernacular, local, multilingual, intersectional, indigenous, postcolonial, race, caste, pedagogy, influence This seminar investigates what Shakespeare has meant and now means in erstwhile colonial geographies (especially those under the British Empire), and how the various 21st-century Shakespeares worldwide impact current questions of indigenous rights, marginalised identities, and caste politics in “post”colonial spaces. The violence of colonialism is such that there can be no truly post-colonial state, only a neo-colonial one. Whether under settler-colonialism (as in the US and Canada, Australia, New Zealand) or extractive colonialism (as in the Indian subcontinent, the Caribbean, and the African continent), the most disenfranchised under colonial rule have only ever changed masters upon any political “post”colonialism. Given the massive continued presence of Shakespeare everywhere that British colonial reach flourished, and the conviction among educators and theatre practitioners that the study of Shakespeare can and should inform the language(s) of resisting injustice, this seminar explores the reality of 21st-century Shakespeares in geographies of postcolonial inheritance, such as the Indian subcontinent, continental Africa, the Caribbean, -

1 Shakespeare and Film

Shakespeare and Film: A Bibliographic Index (from Film to Book) Jordi Sala-Lleal University of Girona [email protected] Research into film adaptation has increased very considerably over recent decades, a development that coincides with postmodern interest in cultural cross-overs, artistic hybrids or heterogeneous discourses about our world. Film adaptation of Shakespearian drama is at the forefront of this research: there are numerous general works and partial studies on the cinema that have grown out of the works of William Shakespeare. Many of these are very valuable and of great interest and, in effect, form a body of work that is hybrid and heterogeneous. It seems important, therefore, to be able to consult a detailed and extensive bibliography in this field, and this is the contribution that we offer here. This work aims to be of help to all researchers into Shakespearian film by providing a useful tool for ordering and clarifying the field. It is in the form of an index that relates the bibliographic items with the films of the Shakespearian corpus, going from the film to each of the citations and works that study it. Researchers in this field should find this of particular use since they will be able to see immediately where to find information on every one of the films relating to Shakespeare. Though this is the most important aspect, this work can be of use in other ways since it includes an ordered list of the most important contributions to research on the subject, and a second, extensive, list of films related to Shakespeare in order of their links to the various works of the canon. -

No Fear Shakespeare – Othello (By Sparknotes, Transcription by Alex Woelffer) -1

No Fear Shakespeare – Othello (by SparkNotes, transcription by Alex Woelffer) -1- Original Text Modern Text Act 1, Scene 1 Enter RODMERIGO and IAGO RODERIGO and IAGO enter. RODERIGO RODERIGO Tush! Never tell me. I take it much unkindly Come on, don’t tell me that. I don’t like it that you That thou, Iago, who hast had my purse knew about this, Iago. All this time I’ve thought As if the strings were thine, shouldst know of this. you were such a good friend that I’ve let you spend my money as if it was yours. IAGO IAGO 'Sblood, but you’ll not hear me! If ever I did dream of Damn it, you’re not listening to me! I never such a matter, abhor me. dreamed this was happening—if you find out I did, you can go ahead and hate me. RODERIGO RODERIGO Thou told’st me You told me you hated him. Thou didst hold him in thy hate. IAGO IAGO Despise me I do hate him, I swear. Three of Venice’s most If I do not. Three great ones of the city important noblemen took their hats off to him and 10 (In personal suit to make me his lieutenant) asked him humbly to make me his lieutenant, the Off-capped to him, and by the faith of man second in command. And I know my own worth I know my price, I am worth no worse a place. well enough to know I deserve that position. But But he (as loving his own pride and purposes) he wants to have things his own way, so he Evades them with a bombast circumstance sidesteps the issue with a lot of military talk and 15 Horribly stuffed with epithets of war, refuses their request. -

Shakespeare's Othello Beyond the Boundaries of the Page

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-7917.2015v20n2p11 SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO BEYOND THE BOUNDARIES OF THE PAGE: AN ANALYSIS OF TWO FILMIC PRODUCTIONS Camila Paula Camilotti* Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Abstract: This article aims at observing and analyzing two filmic productions ofWilliam Shakespeare’s Othello. The first, entitled Othello, was directed, produced and starred by Orson Welles in 1952 andthe second, also entitled Othello, was directed by Oliver Parker in 1995. My main interest in studying these two filmic productions is to observe – based on the notions of theatrical adaptation by Jay Halio (2000), Patrice Pavis (1992), and Allan Dessen (2002) – how each director constructed the seduction moment that happens in Scene III, Act III of Shakespeare’s playtext in their filmic productions. The analysis proves that two different conceptions, separated in time and space, are capable of making Shakespeare’s timelessness transcend and make the modern spectators aware of the fact that the human artistic capacity is able to cross unimaginable limits of creativity and transform a great literary work of art in a great (filmic or theatrical) spectacle. Keywords: Shakespeare’s Othello. Welles’ Othello. Parker’s Othello. Conception. I have’t. It is engendered. Hell and night Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light. (II.I 403-404) Whenever a text (in this case, a Shakespearian playtext) crosses the boundaries of the page to live in a theatrical or cinematic medium, with all its visual (and sonorous) elements,it has inevitably to go through several alterations in order to be seen and heard by an audience, in a certain time and space. -

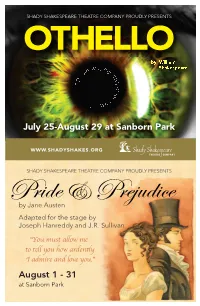

OTHELLO by William Are, M Shakespeare Ew Y B Lo , R D O

SHADY SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY PROUDLY PRESENTS OTHELLO by William are, m Shakespeare ew y b lo , r d O , “ o f j e a l o u s ” y … July 25-August 29 at Sanborn Park WWW.SHADYSHAKES.ORG SHADY SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY PROUDLY PRESENTS Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen Adapted for the stage by Joseph Hanreddy and J.R. Sullivan “You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you.” August 1 - 31 at Sanborn Park Table of Contents Othello Cast ....................................................................................... 2 Othello Synopsis ................................................................................ 2 Othello Director’s Notes ................................................................... 3 Pride and Prejudice Cast ..................................................................... 4 Pride and Prejudice Synopsis .............................................................. 4 Pride and Prejudice Director’s Notes ................................................. 5 2014 Shady Shakespeare Crew ......................................................... 8 A Note from the Managing Director ............................................... 9 Artist Biographies ........................................................................... 10 2014 Sanborn Park Season Schedule ............................................. 13 2014 Season Sponsors .................................................................... 17 2014 Donors .................................................................................. -

25-2-W2016.Pdf

The ESSE Messenger A Publication of ESSE (The European Society for the Study of English Vol. 25-2 Winter 2016 ISSN 2518-3567 All material published in the ESSE Messenger is © Copyright of ESSE and of individual contributors, unless otherwise stated. Requests for permissions to reproduce such material should be addressed to the Editor. Editor: Dr. Adrian Radu Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Faculty of Letters Department of English Str. Horea nr. 31 400202 Cluj-Napoca Romania Email address: [email protected] Cover illustration: Gower Memorial to Shakespeare, Stratford-upon-Avon This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. Picture credit: Immanuel Giel Contents Shakespeare Lives 5 Europe, like Hamlet; or, Hamlet as a mousetrap J. Manuel Barbeito Varela 5 Star-crossed Lovers in Sarajevo in 2002 Ifeta Čirić-Fazlija 14 Shakespeare on Screen José Ramón Díaz Fernández 26 The Interaction of Fate and Free Will in Shakespeare’s Hamlet Özge Özkan Gürcü 57 The Relationship between Literature and Popular Fiction in Shakespeare’s Richard III Jelena Pataki 67 Re-thinking Hamlet in the 21st Century Ana Penjak 79 Reviews 91 Mark Sebba, Shahrzad Mahootian and Carla Jonsson (eds.), Language Mixing and Code-Switching in Writing: Approaches to Mixed-Language Written Discourse (New York & London: Routledge, 2014). 91 Bernard De Meyer and Neil Ten Kortenaar (eds.), The Changing Face of African Literature / Les nouveaux visages de la litterature africaine (Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2009). 93 Derek Hand, A History of the Irish Novel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011). 95 Hobby Elaine. -

OTHELLO Excellent Wretch! Perdition Catch My Soul, but I Do Love Thee! and When I Love Thee Not, Chaos Is Come Again

OTHELLO Excellent wretch! Perdition catch my soul, But I do love thee! and when I love thee not, Chaos is come again. IAGO My noble lord-- OTHELLO What dost thou say, Iago? IAGO Did Michael Cassio, when you woo'd my lady, Know of your love? OTHELLO He did, from first to last: why dost thou ask? IAGO But for a satisfaction of my thought; No further harm. OTHELLO Why of thy thought, Iago? IAGO I did not think he had been acquainted with her. OTHELLO O, yes; and went between us very oft. IAGO Indeed! OTHELLO Indeed! ay, indeed: discern'st thou aught in that? Is he not honest? IAGO Honest, my lord! OTHELLO Honest! ay, honest. IAGO My lord, for aught I know. OTHELLO What dost thou think? IAGO Think, my lord! OTHELLO Think, my lord! By heaven, he echoes me, As if there were some monster in his thought Too hideous to be shown. Thou dost mean something: I heard thee say even now, thou likedst not that, When Cassio left my wife: what didst not like? And when I told thee he was of my counsel In my whole course of wooing, thou criedst 'Indeed!' And didst contract and purse thy brow together, As if thou then hadst shut up in thy brain Some horrible conceit: if thou dost love me, Show me thy thought. IAGO My lord, you know I love you. OTHELLO I think thou dost; And, for I know thou'rt full of love and honesty, And weigh'st thy words before thou givest them breath, Therefore these stops of thine fright me the more: For such things in a false disloyal knave Are tricks of custom, but in a man that's just They are close delations, working from the heart That passion cannot rule. -

Othello and Omkara

Self Love: A Study of Narcissistic Leadership in Film - Othello and Omkara Naheed P. Malbari and Dr. Amanat Ali Jalbani SZABIST Karachi, Pakistan Abstract: In leadership studies, many authors and writers, narcissistic where the latter term was given a negative basically, use examples of real life heroes both historical connotation. and contemporary models, yet the impact of fictional characters is underrated. This interdisciplinary study is This study is not one of psychoanalytical prognosis one such, which fuses many disciplines, namely but one seeing leaders and leadership qualities through the psychology, social science, literature and cinema and same. Thus, the focus is different. religion into one; and to understand the impact it can have The researcher wishes to explore the concept of on people. Narcissistic leadership trait is, therefore, the Narcissistic leadership in film and view things with a subject of study. differing perspective to see the extent to which Cinema, both western and eastern, has depicted this Shakespeare’s main character has influenced others in element. Shakespeare’s plays have often portrayed this cinematic representations of both movies and to denote concept. Thus, I take Othello and Omkara, the Indian what narcissistic leadership qualities Othello and Omkara Shakespearean version and show how each director chose have in common and where they differ. to depict this trait of leadership. Narcissism normally means self-obsession. This complex The interdisciplinary, comparative and descriptive psychological trait is explained keeping in mind recent study focuses on how film can make the understanding of published works by many prominent thinkers, both on a complex psychological phenomenon, like narcissism, an narcissism as well as on leadership (in other words understandable trait for the common man. -

Http//:Daathvoyagejournal.Com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department Of

http//:daathvoyagejournal.com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department of English Dr. K.N. Modi University, Newai, Rajasthan, India. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.1, No.4, December, 2016 Shakespeare on Celluloid, Focusing Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider Dr. Deepa Vanjani Assistant Professor & Head, Dept. of English P.M.B. Gujarati Science College, Indore Abstract: Shakespeare’s legacy lives on. The legacy is by no means a lean one. The immense canvas with mind-boggling characters set in diverse geographical regions remains unparalleled in English drama, as does his rich linguistic legacy. The greatness of William Shakespeare is his contemporariness. It is therefore quite explainable as to how interest in his works never wanes. The profound impact of his plays on cinema has not gone unnoticed. The 21st century has done very well in keeping Shakespeare alive on celluloid. The adaptations of his plays into films have been numerous. In fact film makers have done remarkably well in reinterpreting the Bard’s plays in many languages and thus broadening the reach of his pen. In India film maker Vishal Bhardwaj has succeeded in adapting successfully three tragedies of Shakespeare into three films namely ‘Maqbool’, ‘Omkara’ and ‘Haider’. The three films have received accolades for their dextrous handling of the plot and characters in the three plays they have been inspired by namely ‘Macbeth’, ‘Othello’ and ‘Hamlet’ respectively. The present paper attempts to look into adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays into cinema, in particular Vishal Bhardwaj’s films with the focus being ‘Haider’ made in the year 2014, looking at how he has endeavoured to make alterations in his screenplay and how he fits the Prince of Denmark into present day Kashmir.