Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. I, Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chittagong Branch 56 MD

Sl. No. Name of Investor I.A No 1 REHANA KHAN 17 2 M. ABDUL BARI 22 3 ABDUL BARI 23 4 MD. KAMAL CHOWDHURY 97 5 MD. NURUZZAMAN CHOWDHURY 119 6 RAFIQUR NESSA 154 7 A.S.M. BASHIRUL HUQ 155 8 KAZI ANOWARUL ISLAM 157 9 A.T.M. MAFIZUL ISLAM 159 10 RAZIA BEGUM 178 11 AL-HAJ MD. MOHIUDDIN 180 12 MD. SERAJ DOWLA 182 13 A. K. CHOWDHURY 210 14 MD. BASHIRUL ISLAM CHOWDHURY 224 15 FEROZ ALAM 225 16 MD. MOHIUDDIN(JT) 226 17 LUTFUR RAHMAN (JT) 245 18 MOSLEH UDDIN 266 19 MD. AMIN 278 20 JAHANGIR ALAM 284 21 KAZI HANIF SIDDIQUE 286 22 KAZI ARIFA 287 23 MD. NURUL AMIN 290 24 KAZI MANSURUL ALAM 304 25 REZIA SULTANA 309 26 MD. MOFIZUL HOQUE 310 27 M.A. QUADER 315 28 KAZI MOINUDDIN AHMED 329 29 MD. SHAH ALAM 334 30 A.K.M. NURUL AMIN 335 31 SERAJUDDIN AHMED 359 32 MD. MOHIUDDIN 380 33 HAZARA KHATOON 381 34 MARIAM KHATUN 383 35 BHUPENDRA BHATTACHARJEE 386 36 TASLIMA BEGUM 423 37 TASLIMA BEGUM(JT) 424 38 MRIDUL KANTI DAS 433 39 MD. SHAHEEDULLAH 434 40 SHARIF MOHAMMED JAHANGIR 440 41 ABDUL GAFFAR 459 42 RAFIQ AHMED SIDDIQUE 467 43 MD. SAFI ULLAH 469 44 MD. JOYNAL ABEDIN 499 45 MD. REZAUL ISLAM 513 46 NAZMUL ISLAM 515 47 ROUNOK ARA 534 48 SHAMSUL HOQUE 535 49 TAHMINA BEGUM 589 50 HUSNUL KAMRAIN KHAN 596 51 TARIQUL ISLAM KHAN 597 52 S.M. MESBHAUDDIN 601 53 MD. MAHBUBUDDIN CHY. 604 54 HIRALAL BANIK 606 55 NURUL ALAM 611 Page 1 of 43 ICB Chittagong branch 56 MD. -

Othello, 1955

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Montana Masquers Event Programs, 1913-1978 University of Montana Publications 11-16-1955 Othello, 1955 Montana State University (Missoula, Mont.). Montana Masquers (Theater group) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/montanamasquersprograms Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Montana State University (Missoula, Mont.). Montana Masquers (Theater group), "Othello, 1955" (1955). Montana Masquers Event Programs, 1913-1978. 105. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/montanamasquersprograms/105 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Masquers Event Programs, 1913-1978 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William Shakespeare's Fifty-First Season MONTANA MASQUERS Present William Shakespeare's OTHELLO LEROY W. HINZE, Director CLEMEN M. PECK, Designer and Technical Director •Original Music by MONROE C. DEJARNETTE CAST PRODUCTION STAFF In Order of Appearance Assistant to the Director....Sheila Sullivan Roderigo...............................................Harold Hansen Production Manager for touring company Stage Manager ..................... Ray Halubka | Iago............................................William Nye Electrician .......... ...................Bruce Cusker Brabantio ................................Bruce -

The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice

The Tragedy of Othello, The Moor of Venice. DRAMATIS PERSONAE Duke of Venice [i.e. the Doge] Brabantio, a senator Othello, a noble Moor in the service of the Venetian state Cassio, his lieutenant Iago, his ancient Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman Montano, Othello’s predecessor in the government of Cyprus Desdemona, daughter to Brabantio and wife to Othello Emilia, wife to lago Bianca, mistress to Cassio Written about 1603 Scene: Venice (I act), Cyprus (II, III, IV, V acts) Time: between 1489 (when Catherine Cornaro abdicated and Cyprus became a colony of the Republic of Venice) and 1571 (when Cyprus was conquered by the Ottomans). Most probably in the early 16th century. Sources: Giambattista Giraldi Cinthio (Cinzio)’s (1504-1573) novella “Un capitano moro”, in Hecatommithi (1565), translated into French in 1584, into English only in 1753. 1. ACT I, scene 1 A street in Venice. Night-time […] Rod. What, ho, Brabantio! Signior Brabantio, ho! lago. Awake! what, ho, Brabantio! thieves! thieves! thieves! Look to your house, your daughter and your bags! Thieves! thieves! Brabantio appears above, at a window. Bra. What is the reason of this terrible summons? What is the matter there? Rod. Signior, is all your family within? Iago. Are your doors lock'd? Bra. Why, wherefore ask you this? Iago. 'Zounds, sir, you're robb'd; for shame, put on your gown; Your heart is burst, you have lost half your soul; IP Even now, now, very now, an old black ram Is tupping your white ewe. Arise, arise; Awake the snorting citizens with the bell, Or else the devil will make a grandsire of you: Arise, I say. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

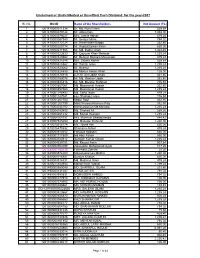

List of Unclaimed Dividend

Unclaimed or Undistributed or Unsettled Cash Dividend for the year-2007 Sl. No. BO ID Name of the Shareholders Net Amount (Tk.) 1 1201470000011334 Dr. Md. Nurul Islam 529.64 2 1201470000079144 Mr. Alaka Das. 7,938.00 3 1201470000079227 Mrs. Jamila Akhter. 479.24 4 1201470000087340 Mr. Serajul Islam. 794.02 5 1201470000173124 Mr. Imran Islam Bappy 352.80 6 1201470000200174 Mr. Asaduzzaman Khan 630.00 7 1201470000271905 Mr. Md. Badrul Alam 1,424.46 8 1201470000323639 Mr. Qayyum Khan Mahbub 1,235.24 9 1201470000329462 Mr. Belayet Hossain Mozumder 479.24 10 1201470000428346 Mrs. Sabina Akther 529.64 11 1201470000428362 Mr. Tanzin Islam 1,235.24 12 1201470000520062 Mr. Ikramul 1,235.24 13 1201470000524459 Md Mokter Hosan Khan 126.00 14 1201470000574918 G.H.M. Arif Uddin Khan 441.66 15 1201470000769078 Mr. Md. Iftekher Uddin 352.80 16 1201470000845416 Mr. Md. Mizanur Rahman 705.60 17 1201470000857067 Md. Mozammel Husain 352.80 18 1201470000857083 Md. Mozammel Husain 1,235.24 19 1201470001146492 Md. Saiful Islam 479.24 20 1201470001147041 kazi Shahidul Islam 176.84 21 1201470001207780 Abdur Rouf 352.80 22 1201470001207799 Most Waresa Khanam Prity 352.80 23 1201470004044792 Moniruzzaman Md.Mostafa 1,235.24 24 1201470004193803 Md. Shahed Ali 265.26 25 1201470004261632 Md. Kamal Hossain 1,235.24 26 1201470004708797 Mrs. Munmun Bhattacharjee 844.42 27 1201470007925659 Md. Masudur Rahman 1,260.00 28 1201470010616174 Ms. Hosna Ara 630.00 29 1201470016475332 Shamima Akhter 479.24 30 1201480000970352 Faruque Hossain 630.00 31 1201480001717909 Md Abul Kalam 630.00 32 1201480003543312 Santosh Kumar Ghosh 1,235.24 33 1201480004339151 Md. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Program Features Don Byron's Spin for Violin and Piano Commissioned by the Mckim Fund in the Library of Congress

Concert on LOCation The Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation The McKim Fund in the Library of Congress "" .f~~°<\f /f"^ TI—IT A TT^v rir^'irnr "ir i I O M QUARTET URI CAINE TRIO Saturday, April 24, 2010 Saturday, May 8, 2010 Saturday, May 22, 2010 8 o'clock in the evening Atlas Performing Arts Center 1333 H Street, NE In 1925 ELIZABETH SPRAGUE COOLIDGE established the foundation bearing her name in the Library of Congress for the promotion and advancement of chamber music through commissions, public concerts, and festivals; to purchase music manuscripts; and to support musical scholarship. With an additional gift, Mrs. Coolidge financed the construction of the Coolidge Auditorium which has become world famous for its magnificent acoustics and for the caliber of artists and ensembles who have played there. The McKiM FUND in the Library of Congress was created in 1970 through a bequest of Mrs. W. Duncan McKim, concert violinist, who won international prominence under her maiden name, Leonora Jackson, to support the commissioning and performance of chamber music for violin and piano. The audiovisual recording equipment in the Coolidge Auditorium was endowed in part by the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress. Request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 [email protected]. Due to the Library's security procedures, patrons are strongly urged to arrive thirty min- utes before the start of the concert. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the chamber music con- certs. -

Unpinning Desdemona Author(S): Denise A

George Washington University Unpinning Desdemona Author(s): Denise A. Walen Source: Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 58, No. 4 (Winter, 2007), pp. 487-508 Published by: Folger Shakespeare Library in association with George Washington University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4625012 . Accessed: 22/03/2013 08:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Folger Shakespeare Library and George Washington University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Shakespeare Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 140.233.2.215 on Fri, 22 Mar 2013 08:40:27 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Unpinning Desdemona DENISEA. WALEN ONE OF THE MORE STRIKING DIFFERENCES betweenthe quarto(1622) and the FirstFolio (1623) texts of Othellois in the scene(4.3) thatpresages Desdemona'smurder as Emiliaundresses her and prepares her for bed. While F unfoldsthrough a leisurely112 linesthat include the WillowSong, Q clips alongwith only 62 lines,cutting the sceneby nearlyhalf.1 These two versions also differthematically. F presentsboth Desdemonaand Emiliaas complex characters.By delvingdeeply into her feelings,it portraysan activeand tragically nuancedDesdemona and raisesempathy for her with its psychologicalexpos6. -

Othello, a Tragedy Act 1: Palace

Othello, A Tragedy Act 1: Palace Set - The Duke's Court Iago and Roderigo have started a rumor that Othello won over Desdemona through witchcraft. Before the Duke of Venice, Othello explains that he won Desdemona through his stories of adventure and war. Desdemona confirms this, and insists that she loves Othello. Act 2: Street Set - A Drunkard's Bar Iago gets Cassio drunk and convinces him to start a fight with a rival officer, Roderigo. Cassio accidentally wounds the Governor, and Othello is summoned. Iago tells Othello that it was Cassio that started the fight, and Othello strips Cassio of his title. Iago then tells Cassio that he should attempt to win over Othello through Desdemona. Act 3: Palace Set - Royal Chambers Cassio appeals to Desdemona to help him earn Othello's forgiveness. He leaves before Othello returns, however, and Iago uses this to convince Othello that Desdemona has betrayed him with Cassio. Desedemona makes things worse by attempting to convince Othello to forgive Cassio. Iago steals Desdemona's handkerchief and plants it on Cassio. Act 4: Palace Set - Private Chambers Othello growing suspicious of Desdemona, asks Iago for evidence. Iago suggests that he has seen Cassio with Desdemona's handkerchief. Othello asks Desdemona for her handkerchief, which she confesses that she has lost, and attempts to change the subject by pleading Cassio's case. Act 5: Palace Set - Private Chambers Othello confronts Desdemona, but does not believe her story. He kills her. After her death, he realizes what has happened and confronts Iago. They duel and both are wounded. -

JETRO's Activities to Assist Developing Countries in Africa

JETRO’sJETRO’s Activities Activities to to Assist Assist Developing Developing Countries Countries in in Africa Africa Boosting Africa’s mood through business with Japan! We would like to introduce you to JETRO’s activities aimed at assisting developing countries in Africa and the achievements thereof. Exhibit at IFEX2007 Workshop for improving the quality of Harvesting at tea plantation in Malawi Processing cut flowers Making shea butter soap (International Flower Expo) kiondo bags Photo provided by Fair Trade Company Photo provided by Earth Tea LLC JETRO’s Activities to Assist Developing Countries JETRO is engaged in assisting developing countries in their achievement of sustainable economic growth through activities such as nurturing industry, establishing industrial infrastructure, developing human resources, and implementing projects aimed at developing products for export and to supporting their entry into the Japanese market. Considering the business needs of both Japanese companies and developing countries, JETRO combines various business tools, including the dispatch of experts, the acceptance of trainees, supporting presentations at exhibitions and development and import demonstration projects, all in an organized fashion with a view to supporting the establishment of business relations between Japanese and local companies. Performances for last few years Some of the examples of projects based on needs in developing countries include assistance of exporting products such as cut flowers from East African countries, coffee from Zambia, tea from Malawi and various natural products (oils, herbal teas and spices) to Japan. Bright-colored flowers, high-quality Zambian coffee, mellow flavored Malawian tea that goes perfectly with milk are beginning to permeate the Japanese market, and are expected to further increase in sales in Japan in the future. -

Unclaimed Dividend All.Xlsx

Biritish American Tobacco Bangladesh Company Limited Unclaimed Dividend List SL ID No Shareholder Name Amount 1 01000013 ASRARUL HOSSAIN 760,518.97 2 01000022 ANWARA BEGUM 132,255.80 3 01000023 ABUL BASHER 22,034.00 4 01000028 AZADUR RAHMAN 318,499.36 5 01000029 ABDUL HAKIM BHUYAN 4,002.32 6 01000040 AKHTER IQBAL BEGUM 12,239.10 7 01000045 ASHRAFUL HAQUE 132,017.80 8 01000046 AKBAR BEPARI AND ABDUL MAJID 14,249.34 9 01000071 ABDUS SOBHAN MIAH 93,587.85 10 01000079 AMIYA KANTI BARUA 23,191.92 11 01000088 A.M.H. KARIM 277,091.10 12 01000094 AFSARY SALEH 59,865.60 13 01000103 ABDUL QUADER 4,584.85 14 01000107 A. MUJAHID 384,848.74 15 01000116 ABDUL MATIN MAZUMDER 264.60 16 01000128 ABDUL GAFFAR 216,666.00 17 01000167 ATIQUR RAHMAN 2,955.15 18 01000183 A. MANNAN MAZUMDAR 15,202.30 19 01000188 AGHA AHMED YUSUF 1,245.00 20 01000190 ALEYA AMIN 897.50 21 01000195 AFTAB AHMED 197,578.88 22 01000207 ABU HOSSAIN KHAN 32,905.05 23 01000225 ABU TALEB 457.30 24 01000233 ASOKE DAS GUPTA 14,088.00 25 01000259 MD. AFSARUDDIN KHAN 293.76 26 01000290 ATIYA KABIR 14,009.19 27 01000309 ABDUR RAUF 151.30 28 01000317 AHMAD RAFIQUE 406.40 29 01000328 A. N. M. SAYEED 5,554.98 30 01000344 AMINUL ISLAM KHAN 20,139.60 31 01000349 ABBADUL-MA'BUD SIDDIQUE 56.25 32 01000385 ALTAFUL WAHED 39,245.70 33 01000402 AYESHA NAHAR 1,668.55 34 01000413 ANOWER SHAFI CHAUDHURY 4,025.74 35 01000436 A. -

Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies: What’S Shakespeare to Them, Or They to Shakespeare

Shakespeare in the “Post”Colonies: What’s Shakespeare To Them, or They to Shakespeare Shakespeare Association of America Annual Meeting 2021 2 April 2021, 8-11am EDT About the Seminar Co-leader: Amrita Dhar (Ohio State University) Co-leader: Amrita Sen (University of Calcutta) Seminar keywords: vernacular, local, multilingual, intersectional, indigenous, postcolonial, race, caste, pedagogy, influence This seminar investigates what Shakespeare has meant and now means in erstwhile colonial geographies (especially those under the British Empire), and how the various 21st-century Shakespeares worldwide impact current questions of indigenous rights, marginalised identities, and caste politics in “post”colonial spaces. The violence of colonialism is such that there can be no truly post-colonial state, only a neo-colonial one. Whether under settler-colonialism (as in the US and Canada, Australia, New Zealand) or extractive colonialism (as in the Indian subcontinent, the Caribbean, and the African continent), the most disenfranchised under colonial rule have only ever changed masters upon any political “post”colonialism. Given the massive continued presence of Shakespeare everywhere that British colonial reach flourished, and the conviction among educators and theatre practitioners that the study of Shakespeare can and should inform the language(s) of resisting injustice, this seminar explores the reality of 21st-century Shakespeares in geographies of postcolonial inheritance, such as the Indian subcontinent, continental Africa, the Caribbean,