Dairy Farmer Profitability Using Intensive Rotational Stocking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costs to Implement Rotational Grazing

Do You Have Problems With: • Low pasture yields • Low quality pasture • Weeds in the pasture • Poor livestock condition • Supplementing hay in summer pastures • Large bare spots in the pasture • Numerous livestock paths across the pasture Rotational grazing provides higher quality and better Rotational Grazing Can Help yielding forage. Benefits of Rotational Grazing: • Increased pasture yields • Better quality pastures • Carry more animals on the same acreage • Feed less hay • Better distribution of manure nutrients throughout the pasture • Healthier livestock • Improved income ($$) Healthy pastures = Healthy and productive livestock Costs to Implement Rotational Grazing • Example: A 40 acre pasture divided into 4 pastures can cost as little as $200 for single strand fencing. • To distribute water will be about $.50/foot of water line. • A portable watering trough costs about $100 to $160. Portable watering tank connected to a hose Rotational Grazing Components needed: • Light-weight fencing to subdivide large pasture areas – poly-wire, poly-tape, high tensile wire, electric netting, reels, rods for stringing fence on, fence charger, ground rods, lightning arrestors • Portable water troughs with pipeline if stationary trough is over 800 feet away from some of the pasture area • Handling area for livestock used to load and unload animals or work on them Planning a rotational grazing system A low cost single strand fence works well for dividing pastures. A rotational grazing system works best when the num- ber of livestock equals the carrying capacity of the pas- ture system. If livestock are overstocked then addi- tional hay will need to be provided. Generally 20-30 days are needed to rest pastures dur- ing rapid growth periods and 40 or more days during slow growth periods. -

A Biodiversity-Friendly Rotational Grazing System Enhancing Flower

A biodiversity-friendly rotational grazing system enhancing flower-visiting insect assemblages while maintaining animal and grassland productivity Simone Ravetto Enri, Massimiliano Probo, Anne Farruggia, Laurent Lanore, Andre Blanchetete, Bertrand Dumont To cite this version: Simone Ravetto Enri, Massimiliano Probo, Anne Farruggia, Laurent Lanore, Andre Blanchetete, et al.. A biodiversity-friendly rotational grazing system enhancing flower-visiting insect assemblages while maintaining animal and grassland productivity. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, Elsevier Masson, 2017, 241, pp.1-10. 10.1016/j.agee.2017.02.030. hal-01607171 HAL Id: hal-01607171 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01607171 Submitted on 26 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 241 (2017) 1–10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agee A biodiversity-friendly -

Delivering on Net Zero: Scottish Agriculture

i Delivering on Net Zero: Scottish Agriculture A report for WWF Scotland from the Organic Policy, Business and Research Consultancy Authors: Nic Lampkin, Laurence Smith, Katrin Padel NOVEMBER 2019 ii Contents Executive summary............................................................................................................................................ iii 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Portfolio of mitigation measures ............................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Measuring greenhouse gas emissions and global warming potential .............................................. 3 2.3 Emission reduction measures to be analysed ................................................................................... 5 A. Improved nitrogen fertiliser use ............................................................................................................... 5 2.3.1 M1 (E1, FBC): Improving synthetic N utilisation ........................................................................ 5 2.3.2 M2 (E6): Controlled release fertilisers (CRF) ............................................................................. 6 2.3.3 M3 (E10): Precision applications to crops ................................................................................ -

Livestock Performance for Sheep and Cattle Grazing Lowland Permanent Pasture: Benchmarking Potential of Forage-Based Systems

agronomy Article Livestock Performance for Sheep and Cattle Grazing Lowland Permanent Pasture: Benchmarking Potential of Forage-Based Systems Robert J. Orr 1, Bruce A. Griffith 1, M. Jordana Rivero 1,* and Michael R. F. Lee 1,2 1 Rothamsted Research, Sustainable Agriculture Sciences, North Wyke, Okehampton, Devon EX20 2SB, UK; [email protected] (R.J.O.); bruce.griffi[email protected] (B.A.G.); [email protected] (M.R.F.L.) 2 University of Bristol, Bristol Veterinary School, Langford, Somerset BS40 5DU, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-1837-512302 Received: 29 January 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2019; Published: 21 February 2019 Abstract: Here we describe the livestock performance and baseline productivity over a two-year period, following the establishment of the infrastructure on the North Wyke Farm Platform across its three farmlets (small farms). Lowland permanent pastures were continuously stocked with yearling beef cattle and ewes and their twin lambs for two years in three farmlets. The cattle came into the farmlets as suckler-reared weaned calves at 195 32.6 days old weighing 309 45.0 kg, were ± ± housed indoors for 170 days then turned out to graze weighing 391 54.2 kg for 177 days. Therefore, ± it is suggested for predominantly grass-based systems with minimal supplementary feeding that target live weight gains should be 0.5 kg/day in the first winter, 0.9 kg/day for summer grazing and 0.8 kg/day for cattle housed and finished on silage in a second winter. The sheep performance suggested that lambs weaned at 100 days and weighing 35 kg should finish at 200 days weighing 44 to 45 kg live weight with a killing out percentage of 44%. -

Future Friendly Farming: Seven Agricultural Practices to Sustain People and the Environment Executive Summary

Future Friendly Farming Seven Agricultural Practices to Sustain People and the Environment Ryan Stockwell and Eliav Bitan August 2011 Future Friendly Farming Seven Agricultural Practices to Sustain People and the Environment Ryan Stockwell and Eliav Bitan August 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank the contributions of many people in the development of this report. Julie Sibbing and Aviva Glaser provided guidance and editing. Bill McGuire provided content and consulted on the development of the report. Mekell Mikell provided insightful edits. A number of reviewers provided helpful feedback on various drafts of this report. We appreciate the time everyone took to talk with us about their practices or projects. Finally we would like to thank the Packard Foundation for their support of this project. Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................1 Introduction ................................................................................................3 CHART: Multiple benefits of agriculture and land management practices ......................................................................4 1. Cover Crops ...........................................................................................5 CASE STUDY: Minnesota Corn and Soybean Farmer Grows Profits, as well as Water Quality and Climate Benefits .........................................................................6 CASE STUDY: Cover Cropping North Dakota Grain and Cattle Farmers Grow Profits, as -

Intensive Rotational Grazing of Romney Sheep As a Control for the Spread of Persicaria Perfoliata

INTENSIVE ROTATIONAL GRAZING OF ROMNEY SHEEP AS A CONTROL FOR THE SPREAD OF PERSICARIA PERFOLIATA A Final Report of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program Caroline B. Girard Polgar Fellow Biodiversity, Conservation and Policy Program University at Albany Albany, NY 12222 Project Advisor: G.S. Kleppel Biodiversity, Conservation and Policy Program Department of Biological Sciences University at Albany Albany, NY 12222 Girard, C.B. and Kleppel, G.S. 2011. Intensive Rotational Grazing of Romney Sheep as a Control for the Spread of Persicaria perfoliata. Section III: 1-22 In D.J. Yozzo, S.H. Fernald and H. Andreyko (eds.), Final Reports of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program, 2009. Hudson River Foundation. III- 1 ABSTRACT The invasive species Persicaria perfoliata (mile-a-minute) is threatening native plant communities by displacing indigenous plant species in 10 of the coterminous United States including New York. This study investigated the effectiveness of a novel protocol, intensive rotational targeted grazing, for controlling the spread of P. perfoliata. Three Romney ewes (Ovis aries) were deployed into a system of four experimental paddocks, each approximately 200 m2, at sites invaded by P. perfoliata in the Ward Pound Ridge Reservation (Cross River, Westchester County, NY). The ewes were moved from one experimental paddock to the next at 2-3 d intervals. Four adjacent, ungrazed reference paddocks were also delineated for comparison with the experimental paddocks. A suite of plant community attributes (cover classes, species richness and composition), as well attributes of individual P. perfoliata plants (stem density, inflorescence) were monitored in the experimental and reference paddocks from June 24 to August 7, 2009. -

Assessment of Cultural Practices in the High Mountain Eastern Mediterranean Landscape Al-Shouf Cedar Society CEPF

Assessment of Cultural Practices in the High Mountain Eastern Mediterranean Landscape Al-Shouf Cedar Society CEPF 0 INDEX The Study Area- Shouf Biosphere Reserve 02 Introduction 03 1. The Shouf Biosphere Reserve (SBR) ……………………………………………….……………………………………………………… 04 A. Legal status of the Shouf Biosphere Reserve 04 B. Physical characteristics 04 C. Natural characteristics 05 D. Socio-economic feature 07 2. Assessment……………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………………………….. 09 • Literature Review 09 • Overview 10 • Introduction 11 A. Traditional agricultural practices in the Levantine Mountains 12 B. Some general recommendations 13 C. Guidelines 15 D. Traditional Agricultural Techniques 24 E. Best Agricultural Practices 25 F. Additional Best Management Practices 26 G. Livestock: 30 • Conclusion of Literature Review: 31 • Special mention 32 • References in English: 34 3. Biodiversity in Lebanon……………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………………………………….. 37 4. Survey……………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………………………………………….………… 41 5. Monitoring of Biodiversity Programme in the Shouf Biosphere ………………….…. 42 Reserve 6. Biodiversity and Cultural Practices at the at the SBR……………………………………………….…….. 47 7. Recommendations……………………………………………….……………………………………………….……………………………………………….………………… 48 A. Agriculture: 49 B. Water management: 51 C. Promotion of Ecotourism: 52 8. Information sheet……………………….……………………………………………….……………………………………………….………………………………………….. 54 A. Agriculture 54 B. Grazing 60 1 The Study Area- Shouf Biosphere Reserve 2 -

Chapter 7 Meadows and Enclosed Pasture

Meadows and enclosed pasture 7 Definition and location of meadows and enclosed pasture ................................ 7:3 7.1 Definition of meadows and enclosed pasture ....................................... 7:3 7.2 Location and extent of meadows and enclosed pasture .............................. 7:4 Habitats and species of meadows and enclosed pasture in the uplands ..................... 7:5 7.3 Why meadows and enclosed pasture are important ................................. 7:5 7.4 Habitats and species of meadows and enclosed pasture, their nature conservation status and distribution ................................................................... 7:5 7.4.1 Vascular plants ......................................................... 7:5 7.4.2 Bryophytes ............................................................. 7:6 7.4.3 Plant communities ...................................................... 7:6 7.4.4 Birds .................................................................. 7:8 7.4.5 Invertebrates ........................................................... 7:9 7.4.6 Mammals ............................................................. 7:10 7.4.7 Amphibians and reptiles ................................................ 7:10 7.5 Habitat and management requirements of meadow and enclosed pasture species ...... 7:10 Management of upland meadows and enclosed pasture .................................. 7:11 7.6 Managing upland meadows and enclosed pasture ................................. 7:11 7.6.1 Establishing management objectives -

Regenerative Consumer TOOLKIT Find Food, Fiber and Other Goods Produced in a Way That Slows Down Climate Change

Regenerative Consumer TOOLKIT Find food, fiber and other goods produced in a way that slows down climate change Hear the buzz about regenerative farming, but not sure what that means for YOU? Want to find carbon-farmed goods? Want to #changeclimatechange in a way that feels empowering and tastes amazing? Then read on. Photo: Shawn Linehan In a world so filled with problems that it’s easy to feel overwhelmed, here’s a bit of good news: Farmers and scientists around the world are confirming time and time again that a major climate solution lies in something as simple as soil: healthy soil can absorb excess carbon from the atmosphere and store it safely for long periods of time. The practices for increasing this capacity in the soil are low-tech, low-cost, and accessible, and bring with them numerous other environmental benefits. We call them regenerative farming practices. This is farming that can help to slow down or potentially even reverse global warming. So there it is. Farming doesn’t have to be destructive, it can be restorative. The way you meet your daily material needs doesn’t have to be destructive, it can be restorative. You don’t need to be a farmer to participate in this regenerative revolution. If you eat food, wear clothes, or use any products that can be traced back to farm- land somewhere, you are already a part of the equation that can make this work. You already have a say. And it’s quite simple: By supporting regenerative farms and companies that source from them, YOU can help to slow down or potentially even reverse global warming. -

Socio-Demographic and Economic Characteristics, Crop-Livestock Production Systems and Issues for Rearing Improvement: a Review

Available online at http://www.ifgdg.org Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 12(1): 519-541, February 2018 ISSN 1997-342X (Online), ISSN 1991-8631 (Print) Review Paper http://ajol.info/index.php/ijbcs http://indexmedicus.afro.who.int Socio-demographic and economic characteristics, crop-livestock production systems and issues for rearing improvement: A review Daniel Bignon Maxime HOUNDJO1, Sébastien ADJOLOHOUN1*, Basile GBENOU1, Aliou SAIDOU2, Léonard AHOTON2, Marcel HOUINATO1, Soumanou SEIBOU TOLEBA1 and Brice Augustin SINSIN3 1Département de Production Animale, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, 03 BP 2819 Jéricho, Cotonou, Benin. 2Département de Production Végétale, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, 03 BP 2819 Jéricho, Cotonou, Benin. 3Département de l’Aménagement et Gestion des Ressources Naturelles, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université d’Abomey-Calavi, 03 BP 2819 Jéricho, Cotonou, Benin. *Corresponding author; E-mail : [email protected]; Tél: (+229) 97 89 88 51 ABSTRACT This paper reviews some characteristics of crop-livestock production systems in Benin with a special focus on the issues for enhance pasture production and nutritive value which in turn will increase animal productivity. Benin is located in the Gulf of Guinea of the Atlantic Ocean in West Africa and covers 114,763 km2. The population estimated in 2017 is 10,900,000 inhabitants with an annual population growth rate of 3.5%. The country is primarily an agro-based economy, characterized by subsistence agricultural production that employs more than 70%. The climate ranges from the bimodal rainfall equatorial type in the south to the tropical unimodal monsoon type in the north. -

What Is Rotational Grazing and Why Is It So Important?

What is Rotational Grazing and Why Is It So Important? To address environmental, economic and social issues through one method of agricultural management affecting the most acreage, choose grazing. Rotational grazing, management‐intensive grazing, rational grazing or holistic grazing are all methods to describe the movement of animals through subdivided pasture areas. The key elements to a successful grazing system are the limited time animals stay in each paddock and the amount of rest the pasture plants receive before being grazed again. In a healthy grazing system plant roots grow deeply into the ground, plant leaves harvest solar energy and cycles of water, minerals, energy and community dynamics are in balance. 1) Grazing has been proven to lower feed expenses, reduce nutrient loading in our waterways, stabilize farm financial longevity, and create an aesthetic working landscape. With the increasing pressures on Vermont farms, these benefits are critical to maintaining many farms in this state. 2) Research has shown that grazing production systems require less fuel than those that depend heavily on machinery and pesticide inputs, drying crops, ventilating buildings and the use of inorganic fertilizers. 3) Because much of the agricultural land in the state is best suited for forage production because of soil, site and climatic limitations, sustainability of agriculture in the region depends on keeping forage‐based livestock systems competitive and profitable while protecting the environment. 4) Consumers are choosing grass‐fed meat and milk on stores shelves, as measured through the 2010 Vermonter Poll. 49% of respondents indicated they purchased grass‐fed meat in the previous 12 months. -

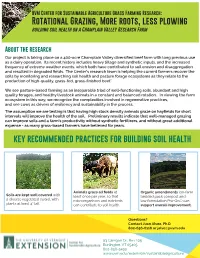

Rotational Grazing, More Roots, Less Plowing Key Recommended

UVM Center for Sustainable Agriculture Grass Farming Research: Rotational Grazing, More roots, less plowing building soil health on a Champlain Valley Research Farm About the research Our project is taking place on a 400-acre Champlain Valley diversified beef farm with long previous use as a dairy operation. Its recent history includes heavy tillage and synthetic inputs, and the increased frequency of extreme weather events, which both have contributed to soil erosion and disaggregation and resulted in degraded fields. The Center’s research team is helping the current farmers recover the soils by monitoring and researching soil health and pasture forage ecosystems as they relate to the production of high-quality, grass-fed, grass-finished beef.’ We see pasture-based farming as an inseparable triad of well-functioning soils, abundant and high quality forages, and healthy livestock animals in a constant and balanced rotation. In viewing the farm ecosystem in this way, we recognize the complexities involved in regenerative practices, and see cows as drivers of resiliency and sustainability in the process. The assumption we are testing is that having high stock density animals graze on hayfields for short intervals will improve the health of the soil. Preliminary results indicate that well-managed grazing can improve soils and a farm’s productivity without synthetic fertilizers, and without great additional expense - as many grass-based farmers have believed for years. key recommended practices for building soil health Animals graze all fields at Organic amendments (on-farm Soils are kept well covered with least once per year, so that bedded pack compost and a diverse vegetated sward, with microorganisms and nutrients low formulation Pro-Gro*) can plants at least 4” tall.