Silvopasture Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Most Effective Way to Reduce Population Growth And

Ariana Shapiro TST BOCES New Visions - Ithaca High School Ithaca, NY Kenya, Factor 17 Slowing Population Growth and Urbanization Through Education, Sustainable Agriculture, and Public Policy Initiatives in Kenya Kenya is a richly varied and unique country. From mountains and plains to lowlands and beaches, the diversity within the 224,961 square miles is remarkable. Nestled on the eastern coast of Africa, Kenya is bordered by Tanzania, Uganda, Ethiopia, Somalia, and the Indian Ocean. Abundant wildlife and incredible biodiversity make Kenya a favorable tourist attraction, and tourism is the country’s best hard currency earner (BBC). However, tourism only provides jobs for a small segment of the population. 75 percent of Kenyans make their living through agriculture (mostly without using irrigation), on the 8.01 percent of land that is classified as arable (CIA World Factbook). As a result, agricultural activity is very concentrated in the fertile coastal regions and some areas of the highlands. Subsistence farmers grow beans, cassava, potatoes, maize, sorghum, and fruit, and some grow export crops such as tea, coffee, horticulture and pyrethrum (HDR). Overgrazing on the arid plateaus and loss of soil and tree cover in croplands has primed Kenya for recurring droughts followed by floods in the rainy seasons. The increasing environmental degradation has had a profound effect on the people of Kenya by forcing farmers onto smaller plots of land too close to other subsistence farms. Furthermore, inequitable patterns of land ownership and a burgeoning population have influenced many poor farmers to move into urban areas. The rapidity of urbanization has resulted in poorly planned cities that are home to large and unsafe slums. -

Costs to Implement Rotational Grazing

Do You Have Problems With: • Low pasture yields • Low quality pasture • Weeds in the pasture • Poor livestock condition • Supplementing hay in summer pastures • Large bare spots in the pasture • Numerous livestock paths across the pasture Rotational grazing provides higher quality and better Rotational Grazing Can Help yielding forage. Benefits of Rotational Grazing: • Increased pasture yields • Better quality pastures • Carry more animals on the same acreage • Feed less hay • Better distribution of manure nutrients throughout the pasture • Healthier livestock • Improved income ($$) Healthy pastures = Healthy and productive livestock Costs to Implement Rotational Grazing • Example: A 40 acre pasture divided into 4 pastures can cost as little as $200 for single strand fencing. • To distribute water will be about $.50/foot of water line. • A portable watering trough costs about $100 to $160. Portable watering tank connected to a hose Rotational Grazing Components needed: • Light-weight fencing to subdivide large pasture areas – poly-wire, poly-tape, high tensile wire, electric netting, reels, rods for stringing fence on, fence charger, ground rods, lightning arrestors • Portable water troughs with pipeline if stationary trough is over 800 feet away from some of the pasture area • Handling area for livestock used to load and unload animals or work on them Planning a rotational grazing system A low cost single strand fence works well for dividing pastures. A rotational grazing system works best when the num- ber of livestock equals the carrying capacity of the pas- ture system. If livestock are overstocked then addi- tional hay will need to be provided. Generally 20-30 days are needed to rest pastures dur- ing rapid growth periods and 40 or more days during slow growth periods. -

A Biodiversity-Friendly Rotational Grazing System Enhancing Flower

A biodiversity-friendly rotational grazing system enhancing flower-visiting insect assemblages while maintaining animal and grassland productivity Simone Ravetto Enri, Massimiliano Probo, Anne Farruggia, Laurent Lanore, Andre Blanchetete, Bertrand Dumont To cite this version: Simone Ravetto Enri, Massimiliano Probo, Anne Farruggia, Laurent Lanore, Andre Blanchetete, et al.. A biodiversity-friendly rotational grazing system enhancing flower-visiting insect assemblages while maintaining animal and grassland productivity. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, Elsevier Masson, 2017, 241, pp.1-10. 10.1016/j.agee.2017.02.030. hal-01607171 HAL Id: hal-01607171 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01607171 Submitted on 26 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 241 (2017) 1–10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agee A biodiversity-friendly -

Connecting Genetic Diversity and Threat Mapping to Set Conservation Priorities for Juglans Regia L

fevo-08-00171 June 19, 2020 Time: 17:54 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 23 June 2020 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00171 Diversity Under Threat: Connecting Genetic Diversity and Threat Mapping to Set Conservation Priorities for Juglans regia L. Populations in Central Asia Hannes Gaisberger1,2*, Sylvain Legay3, Christelle Andre3,4, Judy Loo1, Rashid Azimov5, Sagynbek Aaliev6, Farhod Bobokalonov7, Nurullo Mukhsimov8, Chris Kettle1,9 and Barbara Vinceti1 1 Bioversity International, Rome, Italy, 2 Department of Geoinformatics, University of Salzburg, Salzburg, Austria, 3 Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology, Belvaux, Luxembourg, 4 New Zealand Institute for Plant and Food Research Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand, 5 Bioversity International, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 6 Kyrgyz National Agrarian University named after K. I. Skryabin, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, 7 Institute of Horticulture and Vegetable Growing of Tajik Academy Edited by: of Agricultural Sciences, Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 8 Republican Scientific and Production Center of Ornamental Gardening David Jack Coates, and Forestry, Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 9 Department of Environmental System Science, ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), Australia Central Asia is an important center of diversity for common walnut (Juglans regia L.). Reviewed by: We characterized the genetic diversity of 21 wild and cultivated populations across Bilal Habib, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. A complete threat assessment was performed Wildlife Institute of India, -

Land Degradation and the Australian Agricultural Industry

LAND DEGRADATION AND THE AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY Paul Gretton Umme Salma STAFF INFORMATION PAPER 1996 INDUSTRY COMMISSION © Commonwealth of Australia 1996 ISBN This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial usage or sale requires prior written permission from the Australian Government Publishing Service. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Commonwealth Information Services, AGPS, GPO Box 84, Canberra ACT 2601. Enquiries Paul Gretton Industry Commission PO Box 80 BELCONNEN ACT 2616 Phone: (06) 240 3252 Email: [email protected] The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the Industry Commission. Forming the Productivity Commission The Federal Government, as part of its broader microeconomic reform agenda, is merging the Bureau of Industry Economics, the Economic Planning Advisory Commission and the Industry Commission to form the Productivity Commission. The three agencies are now co- located in the Treasury portfolio and amalgamation has begun on an administrative basis. While appropriate arrangements are being finalised, the work program of each of the agencies will continue. The relevant legislation will be introduced soon. This report has been produced by the Industry Commission. CONTENTS Abbreviations v Preface vii Overview -

Overgrazing and Range Degradation in Africa: the Need and the Scope for Government Control of Livestock Numbers

Overgrazing and Range Degradation in Africa: The Need and the Scope for Government Control of Livestock Numbers Lovell S. Jarvis Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics University of California, Davis Paper prepared for presentation at International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA) October 1984 Subsequently published in East Africa Economic Review, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1991) Overgrazing and Range Degradation in Africa: The Need and the Scope For Government Control of Livestock Numbers Lovell S. Jarvis1 Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics University of California, Davis Introduction Livestock production has been an integral part of farming systems for hundreds of years in many regions of Africa, but there is little evidence on the herd size or range conditions in the pre- colonial period. The great rinderpest epidemic, 1889 to 1896, severely reduced the cattle population and the human population dependent on it. Some estimate that herds fell to 10% or less of their previous level (Sinclair, 1979). This caused the emergence of forest and brush and the invasion of tsetse in some regions, which further harmed the remaining pastoralists. Since that epidemic the livestock and human populations in most of Africa have grown substantially. By the 1920's, some European observers suggested that systematic overgrazing and range degradation might be occurring as a result of common range, and argued that an alternate land tenure system or external stocking controls were essential to avoid a serious reduction in production. These assertions - whether motivated by concern for herder welfare or eagerness to take over pastoralist land -- have been made repeatedly in subsequent years. -

Late Quaternary Extinctions on California's

Flightless ducks, giant mice and pygmy mammoths: Late Quaternary extinctions on California’s Channel Islands Torben C. Rick, Courtney A. Hofman, Todd J. Braje, Jesu´ s E. Maldonado, T. Scott Sillett, Kevin Danchisko and Jon M. Erlandson Abstract Explanations for the extinction of Late Quaternary megafauna are heavily debated, ranging from human overkill to climate change, disease and extraterrestrial impacts. Synthesis and analysis of Late Quaternary animal extinctions on California’s Channel Islands suggest that, despite supporting Native American populations for some 13,000 years, few mammal, bird or other species are known to have gone extinct during the prehistoric human era, and most of these coexisted with humans for several millennia. Our analysis provides insight into the nature and variability of Quaternary extinctions on islands and a broader context for understanding ancient extinctions in North America. Keywords Megafauna; island ecology; human-environmental interactions; overkill; climate change. Downloaded by [Torben C. Rick] at 03:56 22 February 2012 Introduction In earth’s history there have been five mass extinctions – the Ordovician, Devonian, Permian, Triassic and Cretaceous events – characterized by a loss of over 75 per cent of species in a short geological time period (e.g. 2 million years or less: Barnosky et al. 2011). Although not a mass extinction, one of the most heavily debated extinction events is the Late Quaternary extinction of megafauna, when some two-thirds of large terrestrial mammalian genera (444kg) worldwide went extinct (Barnosky et al. 2004). Explanations for this event include climate change, as the planet went from a glacial to interglacial World Archaeology Vol. -

References SILVOPASTURE

SILVOPASTURE Drawdown Technical Assessment References Abberton, Michael, Richard Conant, Caterina Batello, and others. “Grassland Carbon Sequestration: Management, Policy and Economics.” Integrated Crop Management 11 (2010). http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.454.3291&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Albrecht, A., & Kandji, S. T. (2003). Carbon sequestration in tropical agroforestry systems. Agriculture, ecosystems & environment, 99(1), 15-27. Andrade, Hernán J., Robert Brook, and Muhammad Ibrahim. “Growth, Production and Carbon Sequestration of Silvopastoral Systems with Native Timber Species in the Dry Lowlands of Costa Rica.” Plant and Soil 308, no. 1–2 (May 28, 2008): 11–22. doi:10.1007/s11104-008-9600-x. Benavides, Raquel, Grant B. Douglas, and Koldo Osoro. “Silvopastoralism in New Zealand: Review of Effects of Evergreen and Deciduous Trees on Pasture Dynamics.” Agroforestry Systems 76, no. 2 (October 26, 2008): 327–50. doi:10.1007/s10457-008-9186-6. Calle, Alisia, Florencia Montagnini, Andrés Felipe Zuluaga, and others. “Farmers’ Perceptions of Silvopastoral System Promotion in Quindío, Colombia.” Bois et Forets Des Tropiques 300, no. 2 (2009): 79–94. Clason, Terry R., and Steven H. Sharrow. “Silvopastoral Practices.” North American Agroforestry: An Integrated Science and Practice. ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, Madison, WI, 2000, 119–147. Covey, Kristofer R., Stephen A. Wood, Robert J. Warren, Xuhui Lee, and Mark A. Bradford. “Elevated Methane Concentrations in Trees of an Upland Forest.” Geophysical Research Letters 39, no. 15 (August 16, 2012): L15705. doi:10.1029/2012GL052361. Cubbage, Frederick, Gustavo Balmelli, Adriana Bussoni, Elke Noellemeyer, Anibal Pachas, Hugo Fassola, Luis Colcombet, et al. “Comparing Silvopastoral Systems and Prospects in Eight Regions of the World.” Agroforestry Systems 86, no. -

Intensive Rotational Grazing of Romney Sheep As a Control for the Spread of Persicaria Perfoliata

INTENSIVE ROTATIONAL GRAZING OF ROMNEY SHEEP AS A CONTROL FOR THE SPREAD OF PERSICARIA PERFOLIATA A Final Report of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program Caroline B. Girard Polgar Fellow Biodiversity, Conservation and Policy Program University at Albany Albany, NY 12222 Project Advisor: G.S. Kleppel Biodiversity, Conservation and Policy Program Department of Biological Sciences University at Albany Albany, NY 12222 Girard, C.B. and Kleppel, G.S. 2011. Intensive Rotational Grazing of Romney Sheep as a Control for the Spread of Persicaria perfoliata. Section III: 1-22 In D.J. Yozzo, S.H. Fernald and H. Andreyko (eds.), Final Reports of the Tibor T. Polgar Fellowship Program, 2009. Hudson River Foundation. III- 1 ABSTRACT The invasive species Persicaria perfoliata (mile-a-minute) is threatening native plant communities by displacing indigenous plant species in 10 of the coterminous United States including New York. This study investigated the effectiveness of a novel protocol, intensive rotational targeted grazing, for controlling the spread of P. perfoliata. Three Romney ewes (Ovis aries) were deployed into a system of four experimental paddocks, each approximately 200 m2, at sites invaded by P. perfoliata in the Ward Pound Ridge Reservation (Cross River, Westchester County, NY). The ewes were moved from one experimental paddock to the next at 2-3 d intervals. Four adjacent, ungrazed reference paddocks were also delineated for comparison with the experimental paddocks. A suite of plant community attributes (cover classes, species richness and composition), as well attributes of individual P. perfoliata plants (stem density, inflorescence) were monitored in the experimental and reference paddocks from June 24 to August 7, 2009. -

An Approach for Describing the Effects of Grazing on Soil Quality in Life

sustainability Article An Approach for Describing the Effects of Grazing on Soil Quality in Life-Cycle Assessment Andreas Roesch 1,*, Peter Weisskopf 2, Hansruedi Oberholzer 2, Alain Valsangiacomo 1 and Thomas Nemecek 1 1 Agroscope, LCA Research Group, Reckenholzstrasse 191, CH-8046 Zurich, Switzerland 2 Agroscope, Soil Fertility and Soil Protection Group, Reckenholzstrasse 191, CH-8046 Zurich, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-(0)-58-468-7579 Received: 27 July 2019; Accepted: 30 August 2019; Published: 6 September 2019 Abstract: Describing the impact of farming on soil quality is challenging, because the model should consider changes in the physical, chemical, and biological status of soils. Physical damage to soils through heavy traffic was already analyzed in several life-cycle assessment studies. However, impacts on soil structure from grazing animals were largely ignored, and physically based model approaches to describe these impacts are very rare. In this study, we developed a new modeling approach that is closely related to the stress propagation method generally applied for analyzing compaction caused by off-road vehicles. We tested our new approach for plausibility using a comprehensive multi-year dataset containing detailed information on pasture management of several hundred Swiss dairy farms. Preliminary results showed that the new approach provides plausible outcomes for the two physical soil indicators “macropore volume” and “aggregate stability”. Keywords: soil structure; macropore volume; aggregate stability; compaction; modeling; grazing animal; trampling 1. Introduction Soils are a key component of terrestrial ecosystems and provide multiple ecosystem services to humans, such as provisioning of food, timber, and freshwater. Soil is a natural resource and the basis for agriculture and agricultural food production. -

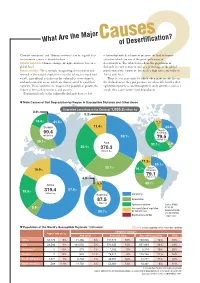

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

Why Dairy Farming and Silvopastoral Agroforestry Could Be The

IFB0219 ISSUE 1.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 13:30 Page 1 TEAT CLIMATE FINANCE DISINFECTANT CHANGE CHANGING HOW TO SELECT SOLUTIONS FARM FROM 100 COW TOILET: STRUCTURES PRODUCTS FACT OR FANTASY? >> SEE PAGE 22 >> SEE PAGE 46 >> SEE PAGE 38 I R I S H VVolumeolume 67 IIssuessue 12 SAutumnpring 2 0/ 1Winter9 Editi o2020n Edition FPPricerice €4.953a.95 / ££4.502.95 ( (Stg)Strg) m BusiDnA eI R YsI NsG PARLOUR PROTOCOLS HELP THE COW & THE MILKING PERSONNEL FARM DESIGN TIMEDEVELOP A MACHINESLONG-TERM PLAN FORYOUR FARM Saving You Time And Money PG 30 HOW GOOD IS YOUR WHICH PHONE IS BEST HOUSEKEEPING FOR SILAGE? FOR FARMERS DAIRY FARMERS PG 24 PG 14 PG 10 IFB0219 ISSUE 1.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 13:30 Page 1 TEAT CLIMATE FINANCE DISINFECTANT CHANGE CHANGING HOW TO SELECT SOLUTIONS FARM FROM 100 COW TOILET: STRUCTURES PRODUCTS FACT OR FANTASY? Foreword/Contents/Credits >> SEE PAGE 22 >> SEE PAGE 46 >> SEE PAGE 38 I R I S H VVolumeolume 67 IIssuessue 12 SAutumnpring 2 0/ 1Winter9 Editi o2020n Edition FPPricerice €4.953a.95 £4.50 £2.95 (Stg) (Strg ) m BusiDnA eI R YsI NsG Features 10 Housekeeping For Dairy Farmers Aidan Kelly of ADPS outlines a list of items that need checking before housing cattle full-time and in particular before the onslaught of the calving period. Planning will make life easier and more safe. PARLOUR PROTOCOLS HELP THE COW & THE MILKING PERSONNEL 14 Which Phone is best for Dairy Farmers? With the increasing reliance on Apps in farming what should you look for in a phone so that it will suit your particular needs? By Dr Diarmuid McSweeney an expert in agri- 10 26 technology.