Palaeo-Philosophy: Archaic Ideas About Space and Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yalin Akcevin the Etruscans Space in Etruscan Sacred Architecture And

Yalin Akcevin The Etruscans Space in Etruscan Sacred Architecture and Its Implications on Use Abstract Space is no doubt an important subject for the Etruscan religion, whether in the inauguration of cities and sacred areas, or in the divination of omens through the Piacenza liver in divided spaces of a sacrificial liver. It is then understandable that in the architecture and layout of the temples and sacred places, the usage of space, bears specific meaning and importance to the use and sanctity of the temple. Exploring the relationship between architectural spaces, and religious and secular use of temple complexes can expand the role of the temple from simply the ritualistic. It can also be shown that temples were both monuments to gods and Etruscans, and that these places were living spaces reflecting the Etruscan sense of spatial relations and importance. I. Introduction The Etruscans, in their own rights, were people whose religion was omnipresent in their daily lives. From deciding upon the fate of battle to the inauguration of cities and sacred spaces, the Etruscans held a sense of religion close to themselves. The most prominent part of this religion however, given what is left from the Etruscans, is the emphasis on the use of space. The division and demarcation of physical space is seen in the orthogonal city plan of Marzabotto with cippus placed at prominent crossroads marking the cardinal directions, to the sixteen parts of the heaven and the sky on the Piacenza liver. Space had been used to divine from lighting, conduct augury from the flight of birds and haruspicy from the liver of sacrificial animals. -

Luce in Contesto. Rappresentazioni, Produzioni E Usi Della Luce Nello Spazio Antico / Light in Context

Light in Antiquity: Etruria and Greece in Comparison Laura Ambrosini Abstract This study discusses lighting devices in Etruria and the comparison with similar tools in Greece, focusing on social and cultural differences. Greeks did not use candlestick- holders; objects that have been improperly identified ascandelabra should more properly be classified as lamp/utensil stands. The Etruscans, on the other hand, preferred to use torchlight for illumination, and as a result, the candelabrum—an upright stand specifically designed to support candles — was developed in order to avoid burns to the hands, prevent fires or problems with smoke, and collect ash or melting substances. Otherwise they also used utensil stands similar to the Greek lamp holders, which were placed near the kylikeion at banquets. Kottaboi in Etruria were important utensils used in the context of banquets and symposia, while in Greece, they were interchangeable with lamp/utensil stands. Introduction Light in Etruria1 certainly had a great importance, as confirmed by the numerous gods connected with light in its various forms (the thunderbolt, the sun, the moon, the dawn, etc.).2 All the religious doctrines and practices concerning the thunderbolt, the light par excellence, are relevant in this concern. Tinia, the most important god of the Etruscan pantheon (the Greek Zeus), is often depicted with a thunderbolt. Sometimes also Menerva (the Greek Athena) uses the thunderbolt as weapon (fig. 1), which does not seem to be attested in Greece.3 Thesan was the Etruscan Goddess of the dawn identified with the Greek Eos; Cavtha is the name of the Etruscan god of the sun in the cult, while Usil is the sun as an appellative or mythological personality. -

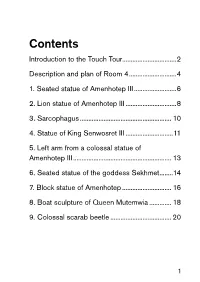

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

1 Name 2 Zeus in Myth

Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus (English pronunciation: /ˈzjuːs/[3] ZEWS); Ancient Greek Ζεύς Zeús, pronounced [zdeǔ̯s] in Classical Attic; Modern Greek: Δίας Días pronounced [ˈði.as]) is the god of sky and thunder and the ruler of the Olympians of Mount Olympus. The name Zeus is cognate with the first element of Roman Jupiter, and Zeus and Jupiter became closely identified with each other. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort The Chariot of Zeus, from an 1879 Stories from the Greek is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Tragedians by Alfred Church. Aphrodite by Dione.[4] He is known for his erotic es- capades. These resulted in many godly and heroic offspring, including Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Hermes, the Proto-Indo-European god of the daytime sky, also [10][11] Persephone (by Demeter), Dionysus, Perseus, Heracles, called *Dyeus ph2tēr (“Sky Father”). The god is Helen of Troy, Minos, and the Muses (by Mnemosyne); known under this name in the Rigveda (Vedic San- by Hera, he is usually said to have fathered Ares, Hebe skrit Dyaus/Dyaus Pita), Latin (compare Jupiter, from and Hephaestus.[5] Iuppiter, deriving from the Proto-Indo-European voca- [12] tive *dyeu-ph2tēr), deriving from the root *dyeu- As Walter Burkert points out in his book, Greek Religion, (“to shine”, and in its many derivatives, “sky, heaven, “Even the gods who are not his natural children address [10] [6] god”). -

Etruscan News 20

Volume 20 20th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE Winter 2018 XXIX Conference of Etruscan and of Giacomo Devoto and Luisa Banti, Italic Studies and where he eventually became Luisa L’Etruria delle necropoli Banti’s successor as Professor of Etruscan Studies at the University of rupestri Florence. Tuscania-Viterbo For twenty years he was the October 26-28, 2017 President of the National Institute of Reviewed by Sara Costantini Etruscan and Italic Studies, with me at his side as Vice President, and for ten From 26 to 28 October, the XXIX years he was head of the historic Conference of Etruscan and Italic Etruscan Academy of Cortona as its Studies, entitled “The Etruria of the Lucumo. He had long directed, along- Rock-Cut Tombs,” took place in side Massimo Pallottino, the Course of Tuscania and Viterbo. The many schol- Etruscology and Italic Antiquities of the ars who attended the meeting were able University for Foreigners of Perugia, to take stock of the new knowledge and and was for some years President of the the problems that have arisen, 45 years Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae after the first conference dedicated to Classicae (LIMC), for which he wrote interior Etruria. The first day’s activi- more than twenty entries. ties, which took place in the Rivellino Cortona, member of the Accademia dei Giovannangelo His activity as field archaeologist Theater “Veriano Luchetti” of Tuscania, Lincei and President of the National Camporeale included the uninterrupted direction, with excellent acoustics, had as their Institute of Etruscan and Italic Studies; 1933-2017 since 1980, of the excavation of the main theme the historical and archaeo- he died on July 1 of this year. -

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum

Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Ancient Carved Ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum Faya Causey With technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael R. Schilling THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES This catalogue was first published in 2012 at http: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data //museumcatalogues.getty.edu/amber. The present online version Names: Causey, Faya, author. | Maish, Jeffrey, contributor. | was migrated in 2019 to https://www.getty.edu/publications Khanjian, Herant, contributor. | Schilling, Michael (Michael Roy), /ambers; it features zoomable high-resolution photography; free contributor. | J. Paul Getty Museum, issuing body. PDF, EPUB, and MOBI downloads; and JPG downloads of the Title: Ancient carved ambers in the J. Paul Getty Museum / Faya catalogue images. Causey ; with technical analysis by Jeff Maish, Herant Khanjian, and Michael Schilling. © 2012, 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust Description: Los Angeles : The J. Paul Getty Museum, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: “This catalogue provides a general introduction to amber in the ancient world followed by detailed catalogue entries for fifty-six Etruscan, Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Greek, and Italic carved ambers from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a The volume concludes with technical notes about scientific copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4 investigations of these objects and Baltic amber”—Provided by .0/. Figures 3, 9–17, 22–24, 28, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 51, and 54 are publisher. reproduced with the permission of the rights holders Identifiers: LCCN 2019016671 (print) | LCCN 2019981057 (ebook) | acknowledged in captions and are expressly excluded from the CC ISBN 9781606066348 (paperback) | ISBN 9781606066355 (epub) BY license covering the rest of this publication. -

Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and Was Thought of As the Personification of Cyclic Law, the Causal Power of Expansion, and the Angel of Miracles

Ζεύς The Angel of Cycles and Solutions will help us get back on track. In the old schools this angel was known as Jupiter (Zeus in the Greek Mysteries) and was thought of as the personification of cyclic law, the Causal Power of expansion, and the angel of miracles. Price, John Randolph (2010-11-24). Angels Within Us: A Spiritual Guide to the Twenty-Two Angels That Govern Our Everyday Lives (p. 151). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. Zeus 1 Zeus For other uses, see Zeus (disambiguation). Zeus God of the sky, lightning, thunder, law, order, justice [1] The Jupiter de Smyrne, discovered in Smyrna in 1680 Abode Mount Olympus Symbol Thunderbolt, eagle, bull, and oak Consort Hera and various others Parents Cronus and Rhea Siblings Hestia, Hades, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter Children Aeacus, Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Dardanus, Dionysus, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces [2] Roman equivalent Jupiter Zeus (Ancient Greek: Ζεύς, Zeús; Modern Greek: Δίας, Días; English pronunciation /ˈzjuːs/[3] or /ˈzuːs/) is the "Father of Gods and men" (πατὴρ ἀνδρῶν τε θεῶν τε, patḕr andrōn te theōn te)[4] who rules the Olympians of Mount Olympus as a father rules the family according to the ancient Greek religion. He is the god of sky and thunder in Greek mythology. Zeus is etymologically cognate with and, under Hellenic influence, became particularly closely identified with Roman Jupiter. Zeus is the child of Cronus and Rhea, and the youngest of his siblings. In most traditions he is married to Hera, although, at the oracle of Dodona, his consort is Dione: according to the Iliad, he is the father of Aphrodite by Dione.[5] He is known for his erotic escapades. -

Work Notes on Bona Dea & the Goddess Uni-A Survey of Etruscan

Work notes on Bona Dea & the goddess Uni — a survey of Etruscan & Latin texts relating to the Pyrgi Gold Tablets By Mel Copeland (Relating to Etruscan Phrases texts) A work in progress November 15, 2014 The Etruscan goddess, Uni, Unia, has been identified with the Roman Juno and, on pottery and mirrors she is portrayed in mythological scenes involving the Greek goddess Hera. Although the Etruscans assigned their own peculiar names to the “Greek” pantheon, such as Tini, Tinia (L. Jupiter, Gr. Zeus), Uni, Unia (L. Juno, Gr. Hera), Turan (L. Venus, Gr. Aphrodite, and Thalna (Gr. Nemisis), many of the Greek characters are recorded with similar spelling in the Etruscan texts, such as Hercle, HerKle, (Gr. Herakles), These (Gr.Theseus), Akle (Gr. Achilles), Ektor (Gr. Hector), Aifas Telmonos (Gr. Ajax Telamonos), Elenei, Elinai (Gr. Helen [of Troy], Elchintre (Alexandar, Paris), Achmemon (Gr. Agememnon) Aeitheon (Gr. Jason) Aita (Gr. Hades) and Dis (Gr. another name of Hades: Dis) and his consort Phersipnei (Gr. Persephone). Because of the imagery used on vases and mirrors and the common Greek mythological themes, we can discern the names and grammatical conventions of Etruscan mythological characters. Because we know who the characters are for the most part and the context in which the Etruscans knew them, we can further understand pure textual documents of the Etruscans, such as the Pyrgi Gold tablets, which will be discussed later in this document, as it pertains to the Roman Feast of the 1st of May called Bona Dea. Uni was identified by the Romans as the Etruscan version of Juno, the consort of their supreme god, Jupiter (Etr. -

1 Egyptian Culture 2 Geography of Egypt 3 4 the Gift of the Nile 5

1 Egyptian Culture 2 Geography of Egypt Nile River is the longest river in the world The Nile creates a ribbon of water in a parched desert 3 4 The Gift of the Nile The predictable flooding of the Nile creates rich soil good for crops The Nile provides a reliable transportation system that promotes trade The desert acted as a natural barrier 5 Environmental Challenges if floods were a few feet below normal 1000’s of ppl starved if floods were higher than normal homes were destroyed desert acted as a natural barrier, but caused Egyptians to live on a small area and have little contact with others, did not have to deal with the constant attacks like the Fertile Crescent. 6 Upper and Lower Egypt Egyptians traveled along the Nile from the mouth to the First Cataract: churning rapids, the cataract area made it impossible to travel to the North past that pt Between the 1st Cataract and the Mediterranean lay 2 different regions Because of its elevation being higher the river area to the South is called Upper Egypt, it is the skinny strip of land from the 1st Cataract to the point where the river starts to fan out into many branches 7 Upper Egypt 8 Upper and Lower Egypt To the North, near the sea, Lower Egypt includes the Nile delta: the 100 miles before the river enters the Mediterranean. The delta is a broad marshy, triangular area of land formed by deposits of silt at the mouth of the river 9 Lower Egypt 10 Egypt unites into a Kingdom 10 Egypt unites into a Kingdom by 3200 BC the villages of Egypt were under the rule of two separate kingdoms, Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt it is believed that a ruler named Scorpion King started uniting Egypt, but it was finished by Narmer Narmer created a combination crown to represent his rule 11 Crowns 12 Pharaohs Rule as Gods In Mesopotamia kings were considered to be representatives of the gods. -

The Birth of Moses

1. THE BIRTH OF MOSES We arrived at Cairo International Airport just after nightfall. Though weary from a day of flying, we were excited to finally set foot on Egyptian soil and to catch a glimpse, by night, of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It took an hour and fifteen minutes to drive from the airport, on the northeast side of Cairo, to Giza, a southern suburb of the city. Even at night the streets were congested with the swelling population of twenty million people who live in greater Cairo. Upon checking into my hotel room, I opened the sliding door to my balcony, and stood for a moment, in awe, as I looked across at the pyramids by night. I was gazing upon the same pyramids that pharaohs, patriarchs, and emperors throughout history had stood before. It was a breathtaking sight. Copyright © by Abingdon21 Press. All rights reserved. 9781501807886_INT_Layout.indd 21 3/10/17 9:00 AM Moses The Pyramids and the Power of the Pharaohs Some mistakenly assume that these pyramids were built by the Israelite slaves whom Moses would lead to freedom, but the pyramids were already ancient when Israel was born. They had been standing for at least a thousand years by the time Moses came on the scene. So, if the Israelites were not involved in the building of these structures, why would we begin our journey—and this book—with the pyramids? One reason is simply that you should never visit Egypt without seeing the pyramids. More importantly, though, we begin with the pyramids because they help us understand the pharaohs and the role they played in Egyptian society. -

Visual Representations of the Birth of Athena/Menrva: a Comparative Study," Etruscan Studies: Vol

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 8 Article 5 2001 Visual Representations of the Birth of Athena/ Menrva: A Comparative Study Shanna Kennedy-Quigley University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Kennedy-Quigley, Shanna (2001) "Visual Representations of the Birth of Athena/Menrva: A Comparative Study," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 8 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol8/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visual RepresenTaTions of The BirTh of AThena/Menrva: A ComparaTive STudy1 by Shanna Kennedy-Quigley he myth of Zeus’s miraculous ProPagation of Athena is the subject not only of such TGreek Poetic masters as Hesiod, Homer, Aeschylus, and EuriPides, but a favorite as well among Archaic and Classical Greek artists, eventually coming to occuPy the East Pediment of the Parthenon.2 PerhaPs through the imPortation of such Portable art- works as Painted vases, the Etruscans were exPosed to the legend, the fundamental iconog- raPhy of which they assimilated and transformed. The PurPose of this study is to demon- strate that Etruscan deviations from Greek archetyPes for rePresenting the birth of Athena exemPlify Etruscan cultural attitudes toward women, which differ significantly from those of their Greek contemPoraries. This study will examine Etruscan rePresentations of the myth, noting Etruscan dePartures from Greek archetyPes and demonstrating that these vari- ations reflect the comParatively liberated status of women in Etruria. -

Print This Article

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections MARRIAGE AND PARENTHOOD ON CLASSICAL PERIOD BRONZE MIRRORS : T HE CASE OF LATVA AND TUNTLE Alexandra A. Carpino Northern Arizona University ABSTRACT The scenes that enhanced the reverse sides of the Etruscans’ bronze mirrors were not just a form of entertainment. Rather, mirror iconography provided elite Etruscans of both genders with a range of ideas to ponder as they fashioned their appearances daily within the domestic sphere. During the 4th century BCE, the number of depictions of parents drawn from the broad Hellenic repertoire known to the Etruscan aristocracy soars. Two individuals who stand out as particularly popular were Latva (Leda) and Tuntle (Tyndareos), who appear in the context of a specifically Etruscan narrative known as the “Delivery of Elinai’s (Helen’s) Egg.” This study focuses on the social significance of these scenes and the messages they imparted through their compositional structure and the various attributes of the characters depicted. It is suggested that they can be read as promoting positive paradigms of marriage and parenthood that served as enduring inspirations for the mirrors’ users and viewers. uring the 4th and 3rd centuries in Etruria, ponder as they fashioned and refashioned their communities in both the south and the north had to appearances on a daily basis within the private sphere of cDontend with foreign incursions, raids and the their homes. It also offers scholars today a window into consequences of conquest. Despite these challenges, this the mindsets of the artifacts’ aristocratic purchasers/ time in Etruscan history was especially prolific with owners, expressing many of the values and beliefs they respect to the creation and diversity of high quality art: and their families prized from the Archaic period onward.