Appendix 1 Signs and Symptoms of Arthropod-Borne Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia

pathogens Article Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia Species in Amblyomma albolimbatum Ticks from the Shingleback Skink (Tiliqua rugosa) in Southern Western Australia Mythili Tadepalli 1, Gemma Vincent 1, Sze Fui Hii 1, Simon Watharow 2, Stephen Graves 1,3 and John Stenos 1,* 1 Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory, University Hospital Geelong, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (G.V.); [email protected] (S.F.H.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Reptile Victoria Inc., Melbourne 3035, Australia; [email protected] 3 Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Nepean Hospital, NSW Health Pathology, Penrith 2747, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tick-borne infectious diseases caused by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Rick- ettsia are a growing global problem to human and animal health. Surveillance of these pathogens at the wildlife interface is critical to informing public health strategies to limit their impact. In Australia, reptile-associated ticks such as Bothriocroton hydrosauri are the reservoirs for Rickettsia honei, the causative agent of Flinders Island spotted fever. In an effort to gain further insight into the potential for reptile-associated ticks to act as reservoirs for rickettsial infection, Rickettsia-specific PCR screening was performed on 64 Ambylomma albolimbatum ticks taken from shingleback skinks (Tiliqua rugosa) lo- cated in southern Western Australia. PCR screening revealed 92% positivity for rickettsial DNA. PCR Citation: Tadepalli, M.; Vincent, G.; amplification and sequencing of phylogenetically informative rickettsial genes (ompA, ompB, gltA, Hii, S.F.; Watharow, S.; Graves, S.; Stenos, J. -

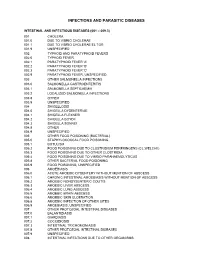

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

Volume - I Ii Issue - Xxviii Jul / Aug 2008

VOLUME - I II ISSUE - XXVIII JUL / AUG 2008 With a worldwide footprint, Rickettsiosis are diseases that are gaining increasing significance as important causes of morbidity and to an extent mortality too. Encompassed within these are two main groups, viz., Rickettsia spotted fever group and the Typhus group (they differ in their surface exposed protein and lipopolysaccharide antigens). A unique thing about these organisms is that, though they are gram-negative bacilli, they 1 Editorial cannot be cultured in the traditional ways that we employ to culture regular bacteria. They Disease need viable eukaryotic host cells and they require a vector too to complete their run up to 2 Diagnosis the human host. Asia can boast of harbouring Epidemic typhus, Scrub typhus, Boutonneuse fever, North Asia Tick typhus, Oriental spotted fever and Q fever. The Interpretation pathological feature in most of these fevers is involvement of the microvasculature 6 (vasculitis/ perivasculitis at various locations). Most often, the clinical presentation initially Trouble is like Pyrexia of Unknown Origin. As they can't be cultured by the routine methods, the 7 Shooting diagnostic approach left is serological assays. A simple to perform investigation is the Weil-Felix reaction that is based on the cross-reactive antigens of OX-19 and OX-2 strains 7 Bouquet of Proteus vulgaris. Diagnosed early, Rickettsiae can be effectively treated by the most basic antibiotics like tetracyclines/ doxycycline and chloramphenicol. Epidemiologically almost omnipresent, the DISEASE DIAGNOSIS segment of this issue comprehensively 8 Tulip News discusses Rickettsiae. Vector and reservoir control, however, is the best approach in any case. -

“Epidemiology of Rickettsial Infections”

6/19/2019 I have got 45 min…… First 15 min… •A travel medicine physician… •Evolution of epidemiology of rickettsial diseases in brief “Epidemiology of rickettsial •Expanded knowledge of rickettsioses vs travel medicine infections” •Determinants of Current epidemiology of Rickettsialinfections •Role of returning traveller in rickettsial diseaseepidemiology Ranjan Premaratna •Current epidemiology vs travel health physician Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya Next 30 min… SRI LANKA •Clinical cases 12 Human Travel & People travel… Human activity Regionally and internationally Increased risk of contact between Bugs travel humans and bugs Deforestation Regionally and internationally Habitat fragmentation Echo tourism 34 This man.. a returning traveler.. down Change in global epidemiology with fever.. What can this be??? • This is the greatest challenge faced by an infectious disease / travel medicine physician • compared to a physician attending to a well streamlined management plan of a non-communicable disease……... 56 1 6/19/2019 Rickettsial diseases • A travel medicine physician… • Represent some of the oldest and most recently recognizedinfectious • Evolution of epidemiology of rickettsial diseases in brief diseases • Expanded knowledge of rickettsioses vs travel medicine • Determinants of Current epidemiology of Rickettsialinfections • Athens plague described during 5th century BC……? Epidemic typhus • Role of returning traveller in rickettsial diseaseepidemiology • Current epidemiology vs travel health physician • Clinical cases 78 In 1916.......... By 1970s-1980s four endemic rickettsioses; a single agent unique to a given geography !!! • R. prowazekii was identified as the etiological agent of epidemic typhus • Rocky Mountain spotted fever • Mediterranean spotted fever • North Asian tick typhus • Queensland tick typhus Walker DH, Fishbein DB. Epidemiology of rickettsial diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 1991 910 Family Rickettsiaceae Transitional group between SFG and TG Genera Rickettsia • R. -

Colorado Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases Fact Sheet No

Colorado Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases Fact Sheet No. 5.593 Insect Series|Trees and Shrubs by W.S. Cranshaw, F.B. Peairs and B.C. Kondratieff* Ticks are blood-feeding parasites of Quick Facts animals found throughout Colorado. They are particularly common at higher elevations. • The most common tick that Problems related to blood loss do occur bites humans and dogs among wildlife and livestock, but they are in Colorado is the Rocky rare. Presently 27 species of ticks are known Mountain wood tick. to occur in Colorado and Table 1 lists the more common ones. Almost all human • Rocky Mountain wood tick is encounters with ticks in Colorado involve most active and does most the Rocky Mountain wood tick. Fortunately, biting in spring, becoming some of the most important tick species dormant with warm weather in present elsewhere in the United States are summer. Figure 1: Adult Rocky Mountain wood tick prior either rare (lone star tick) or completely to feeding. Rocky Mountain wood tick is the most • Colorado tick fever is by far absent from the state (blacklegged tick). common tick that is found on humans and pets in Ticks most affect humans by their ability Colorado. the most common tick- to transmit pathogens that produce several transmitted disease of the important diseases. Diseases spread by ticks region. Despite its name, in Colorado include Colorado tick fever, Rocky Mountain spotted fever Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia and is quite rare here. relapsing fever. • Several repellents are recommended for ticks Life Cycle of Ticks including DEET, picaridin, Two families of ticks occur in Colorado, Figure 2: Adult female and male of the Rocky IR3535, and oil of lemon hard ticks (Ixodidae family) and soft ticks Mountain wood tick. -

| Oa Tai Ei Rama Telut Literatur

|OA TAI EI US009750245B2RAMA TELUT LITERATUR (12 ) United States Patent ( 10 ) Patent No. : US 9 ,750 ,245 B2 Lemire et al. ( 45 ) Date of Patent : Sep . 5 , 2017 ( 54 ) TOPICAL USE OF AN ANTIMICROBIAL 2003 /0225003 A1 * 12 / 2003 Ninkov . .. .. 514 / 23 FORMULATION 2009 /0258098 A 10 /2009 Rolling et al. 2009 /0269394 Al 10 /2009 Baker, Jr . et al . 2010 / 0034907 A1 * 2 / 2010 Daigle et al. 424 / 736 (71 ) Applicant : Laboratoire M2, Sherbrooke (CA ) 2010 /0137451 A1 * 6 / 2010 DeMarco et al. .. .. .. 514 / 705 2010 /0272818 Al 10 /2010 Franklin et al . (72 ) Inventors : Gaetan Lemire , Sherbrooke (CA ) ; 2011 / 0206790 AL 8 / 2011 Weiss Ulysse Desranleau Dandurand , 2011 /0223114 AL 9 / 2011 Chakrabortty et al . Sherbrooke (CA ) ; Sylvain Quessy , 2013 /0034618 A1 * 2 / 2013 Swenholt . .. .. 424 /665 Ste - Anne -de - Sorel (CA ) ; Ann Letellier , Massueville (CA ) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS ( 73 ) Assignee : LABORATOIRE M2, Sherbrooke, AU 2009235913 10 /2009 CA 2567333 12 / 2005 Quebec (CA ) EP 1178736 * 2 / 2004 A23K 1 / 16 WO WO0069277 11 /2000 ( * ) Notice : Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this WO WO 2009132343 10 / 2009 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 WO WO 2010010320 1 / 2010 U . S . C . 154 ( b ) by 37 days . (21 ) Appl. No. : 13 /790 ,911 OTHER PUBLICATIONS Definition of “ Subject ,” Oxford Dictionary - American English , (22 ) Filed : Mar. 8 , 2013 Accessed Dec . 6 , 2013 , pp . 1 - 2 . * Inouye et al , “ Combined Effect of Heat , Essential Oils and Salt on (65 ) Prior Publication Data the Fungicidal Activity against Trichophyton mentagrophytes in US 2014 /0256826 A1 Sep . 11, 2014 Foot Bath ,” Jpn . -

Update on Australian Rickettsial Infections

Update on Australian Rickettsial Infections Stephen Graves Founder & Medical Director Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory Geelong, Victoria & Newcastle NSW. Director of Microbiology Pathology North – Hunter NSW Health Pathology Newcastle. NSW Conjoint Professor, University of Newcastle, NSW What are rickettsiae? • Bacteria • Rod-shaped (0.4 x 1.5µm) • Gram negative • Obligate intracellular growth • Energy parasite of host cell • Invertebrate vertebrate Vertical transmission through life stages • Egg invertebrate Horizontal transmission via • Larva invertebrate bite/faeces (larva “chigger”, nymph, adult ♀) • Nymph • Adult (♀♂) Classification of Rickettsiae (phylum) α-proteobacteria (genus) 1. Rickettsia – Spotted Fever Group Typhus Group 2. Orientia – Scrub Typhus 3. Ehrlichia (not in Australia?) 4. Anaplasma (veterinary only in Australia?) 5. Rickettsiella (? Koalas) NB: Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) is a γ-proteobacterium NOT a true rickettsia despite being tick-transmitted (not covered in this presentation) 1 Rickettsiae from Australian Patients Rickettsia Vertebrate Invertebrate (human disease) Host Host A. Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia i. Rickettsia australis Native rats Ticks (Ixodes holocyclus, (Queensland Tick Typhus) Bandicoots I. tasmani) ii. R. honei Native reptiles (blue-tongue Tick (Bothriocroton (Flinders Island Spotted Fever) lizard & snakes) hydrosauri) iii.R. honei sub sp. Unknown Tick (Haemophysalis marmionii novaeguineae) (Australian Spotted Fever) iv.R. gravesii Macropods Tick (Amblyomma (? Human pathogen) (kangaroo, wallabies) triguttatum) Feral pigs (WA) v. R. felis cats/dogs Flea (cat flea typhus) (Ctenocephalides felis) All these rickettsiae grown in pure culture Rickettsiae in Australian patients (cont.) Rickettsia Vertebrate Invertebrate Host Host B. Typhus Group Rickettsia R. typhi Rodents (rats, mice) Fleas (murine typhus) (Ctenocephalides felis) (R. prowazekii) (humans)* (human body louse) ╪ (epidemic typhus) (Brill’s disease) C. -

Bartonella Henselae Immunoglobulin G and M Titers Were Determined by Using an Immunofl Uorescent Antibody Assay (7)

For 1 patient, we also received a swab from a skin papule. Bartonella henselae Immunoglobulin G and M titers were determined by using an immunofl uorescent antibody assay (7). in Skin Biopsy Skin biopsy specimens and the swab were cultured in human embryonic lung fi broblasts by using the centrifu- Specimens of gation shell-vial technique (3.7 mL; Sterilin Ltd., Felthan, Patients with UK); 12-mm round coverslips seeded with 1 mL of me- dium containing 50,000 cells and incubated in a 5% CO2 Cat-Scratch Disease incubator at 37°C for 3 days were used to obtain a confl u- ent monolayer (8). Cultures were surveyed for 4 weeks and Emmanouil Angelakis, Sophie Edouard, detection of bacteria growth was assessed every 7 days on Bernard La Scola, and Didier Raoult coverslips directly inside the shell vial by using Gimenez and immunofl uorescence staining. We obtained a positive During the past 2 years, we identifi ed live Bartonella culture from 3 patients, and detailed histories are described henselae in the primary inoculation sites of 3 patients after a cat scratch. Although our data are preliminary, we report below (Table). that a cutaneous swab of the skin lesion from a patient in Patient 1 was a 38-year-old man who had fever (40°C) the early stage of cat-scratch disease can be useful for di- and asthenia. The patient was a cat owner who had been agnosis of the infection. scratched 8 days before onset of symptoms. Clinical signs were right axillary lymphadenitis and an infl ammatory red- dish skin lesion on the right hand with epitrochlear adenop- artonella henselae is the main causative agent of cat- athy, which appeared 2 days before he sought treatment. -

Identification and Molecular Characterization of Zoonotic Rickettsiae

Identification and molecular characterization of zoonotic rickettsiae and other vector-borne pathogens infecting dogs in Mnisi, Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa Dr Agatha Onyemowo Kolo A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MAGISTER SCIENTIAE (VETERINARY SCIENCE) In the Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases Faculty of Veterinary Science University of Pretoria South Africa OCTOBER 2014 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation, which I hereby submit for the Master of Science degree in the Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, is my original work and has not been submitted by me for a degree to any other university. SIGNED: DATE: 16-02-2015 AGATHA ONYEMOWO KOLO 2 DEDICATION To the Lord Almighty, the Most High God my Help, my Refuge, my Provider, my Maker, my greatest Love, my Redeemer, my ever Faithful God; to you I dedicate this work. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my gratitude to my Supervisor Prof Paul Tshepo Matjila for his kindness, generosity and support towards me, his acceptance to be my mentor for this specific project I am indeed grateful for the opportunity given to me. To my Co-Supervisors Dr Kgomotso Sibeko-Matjila who painstakingly went through this work with utmost diligence and thoroughness for its success; for her wisdom, humility and approacheability I am most grateful. Dr K I have learnt so much from you may God reward you abundantly for your kindness and dedication. Prof Darryn Knobel for all the extra resources of literature, materials, support and knowledge that he provided his assistance in helping me to think critically and analytically, Sir I am immensely grateful. -

Vaccination with the Variable Tick Protein of the Relapsing Fever Spirochete Borrelia Hermsii Protects Mice from Infection by Tick-Bite Benjamin J

Krajacich et al. Parasites & Vectors (2015) 8:546 DOI 10.1186/s13071-015-1170-1 RESEARCH Open Access Vaccination with the variable tick protein of the relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia hermsii protects mice from infection by tick-bite Benjamin J. Krajacich1, Job E. Lopez2, Sandra J. Raffel3 and Tom G. Schwan3* Abstract Background: Tick-borne relapsing fevers of humans are caused by spirochetes that must adapt to both warm-blooded vertebrates and cold-blooded ticks. In western North America, most human cases of relapsing fever are caused by Borrelia hermsii, which cycles in nature between its tick vector Ornithodoros hermsi and small mammals such as tree squirrels and chipmunks. These spirochetes alter their outer surface by switching off one of the bloodstream- associated variable major proteins (Vmps) they produce in mammals, and replacing it with the variable tick protein (Vtp) following their acquisition by ticks. Based on this reversion to Vtp in ticks, we produced experimental vaccines comprised on this protein and tested them in mice challenged by infected ticks. Methods: The vtp gene from two isolates of B. hermsii that encoded antigenically distinct types of proteins were cloned, expressed, and the recombinant Vtp proteins were purified and used to vaccinate mice. Ornithodoros hermsi ticks that were infected with one of the two strains of B. hermsii from which the vtp gene originated were used to challenge mice that received one of the two Vtp vaccines or only adjuvant. Mice were then followed for infection and seroconversion. Results: The Vtp vaccines produced protective immune responses in mice challenged with O. -

Growing Evidence of an Emerging Tick-Borne Disease That Causes a Lyme-Like Illness for Many Australian Patients

Institute for Molecular Bioscience CRICOS PROVIDER NUMBER 00025B Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 3 March 2016 To the Committee Secretariat: I am a research scientist at The University of Queensland in the Institute for Molecular Bioscience. I have a PhD in Chemistry and a MSc in Entomology (the study of insects), and my research program is focused on the discovery and characterization of novel, environmentally-friendly insecticides. I am now a proud Queenslander, but am also an American citizen and grew up in New England, in the epicentre of Lyme Disease in the United States. Please find below my submission to the Senate Community Affairs References Committee, based on the terms of reference. The growing evidence of an emerging tick-borne disease that causes a Lyme-like illness for many Australian patients. a. the prevalence and geographic distribution of Lyme-like illness in Australia; Lyme Disease is caused by infection with bacteria of the Borrelia type. Lyme disease is a type of borreliosis, and Lyme borreliosis exhibits a range of acute and sometimes chronic multisystemic symptoms [1]. Of the 30 or so known species of Borrelia across the United States and Europe, the majority of human cases are caused by only three species [2,3]. In the United States, Lyme disease is transmitted by ticks in the genus Ixodes, primarily Ixodes scapularis (the deer tick) and I. pacificus (the western blacklegged tick). In Australia, this genus of tick is also present, and is widely distributed along the southern and eastern coastlines (Figure 1). -

The Blue Book: Guidelines for the Control of Infectious Diseases I

The blue book: Guidelines for the control of infectious diseases i The blue book Guidelines for the control of infectious diseases ii The blue book: Guidelines for the control of infectious diseases Acknowledgements Disclaimer These guidelines have been developed These guidelines have been prepared by the Communicable Diseases Section, following consultation with experts in the Public Health Group. The Blue Book – field of infectious diseases and are based Guidelines for the control of infectious on information available at the time of diseases first edition (1996) was used as their preparation. the basis for this update. Practitioners should have regard to any We would like to acknowledge and thank information on these matters which may those who contributed to the become available subsequent to the development of the original guidelines preparation of these guidelines. including various past and present staff Neither the Department of Human of the Communicable Diseases Section. Services, Victoria, nor any person We would also like to acknowledge and associated with the preparation of these thank the following contributors for their guidelines accept any contractual, assistance: tortious or other liability whatsoever in A/Prof Heath Kelly, Victorian Infectious respect of their contents or any Diseases Reference Laboratory consequences arising from their use. Dr Noel Bennett, content editor While all advice and recommendations are made in good faith, neither the Dr Sally Murray, content editor Department of Human Services, Victoria, Ms Kerry Ann O’Grady, content editor nor any other person associated with the preparation of these guidelines accepts legal liability or responsibility for such advice or recommendations. Published by the Communicable Diseases Section Victorian Government Department of Human Services Melbourne Victoria May 2005 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Human Services 2005 This publication is copyright.