Assessing Fever in the Returned Traveller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia

pathogens Article Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia Species in Amblyomma albolimbatum Ticks from the Shingleback Skink (Tiliqua rugosa) in Southern Western Australia Mythili Tadepalli 1, Gemma Vincent 1, Sze Fui Hii 1, Simon Watharow 2, Stephen Graves 1,3 and John Stenos 1,* 1 Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory, University Hospital Geelong, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (G.V.); [email protected] (S.F.H.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Reptile Victoria Inc., Melbourne 3035, Australia; [email protected] 3 Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Nepean Hospital, NSW Health Pathology, Penrith 2747, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tick-borne infectious diseases caused by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Rick- ettsia are a growing global problem to human and animal health. Surveillance of these pathogens at the wildlife interface is critical to informing public health strategies to limit their impact. In Australia, reptile-associated ticks such as Bothriocroton hydrosauri are the reservoirs for Rickettsia honei, the causative agent of Flinders Island spotted fever. In an effort to gain further insight into the potential for reptile-associated ticks to act as reservoirs for rickettsial infection, Rickettsia-specific PCR screening was performed on 64 Ambylomma albolimbatum ticks taken from shingleback skinks (Tiliqua rugosa) lo- cated in southern Western Australia. PCR screening revealed 92% positivity for rickettsial DNA. PCR Citation: Tadepalli, M.; Vincent, G.; amplification and sequencing of phylogenetically informative rickettsial genes (ompA, ompB, gltA, Hii, S.F.; Watharow, S.; Graves, S.; Stenos, J. -

Recognizing and Treating New and Emerging Infections Encountered in Everyday Practice

Recognizing and treating new and emerging infections encountered in everyday practice STEVEN M. GORDON, MD NFECTIOUS DISEASES, pre- MiikWirj:« Although infectious diseases were once considered a dicted earlier in this cen- diminishing threat, new pathogens are constantly challenging tury to be eliminated as a the health care system. This article reviews the clinical presen- public health problem, re- tation, diagnosis, and treatment of seven emerging infections I main the chief cause of death that primary care physicians are likely to encounter. worldwide and a significant cause of death and morbidity in i Parvovirus B19 attacks erythrocyte precursors; the United States.1 Challenging infection is usually benign and self-limiting but can cause the US public health system are aplastic crises in patients with chronic hemolytic disorders. several newly identified patho- Hemorrhagic colitis due to Escherichia coli 0157:H7 infection gens (eg, human immunodefi- can lead to the hemolytic-uremic syndrome, especially in chil- ciency virus [HIV], Escherichia dren; it also can cause thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura. coli 0157:H7, hepatitis C) and a Chlamydia pneumoniae causes a mild pneumonia that resem- resurgence of old diseases pre- bles mycoplasmal pneumonia. Bacillary angiomatosis primar- sumed to be under control (eg, ily affects immunocompromised patients, especially those tuberculosis, syphilis). Further, infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). At least multiple-drug resistance in two organisms can cause bacillary angiomatosis: Bartonella hense- strains of pneumococci, gono- lae and Bartonella quintana. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome cocci, enterococci, staphylo- is spread by exposure to the droppings of infected rodents. cocci, salmonella, and mycobac- Contrary to previous thought, HIV continues to replicate teria undermines efforts to throughout the course of the illness and does not have a latency control the diseases they cause.2 phase. -

Lyme Disease Weather Also Means That Ticks Become More Active and This Can Agent by Feeding As Larvae on Certain Rodent Species

Spring and summer bring warm temperatures, just right for small and medium sized animals, but will also feed on people. walking in the woods and other outdoor activities. Warm These ticks typically become infected with the Lyme disease weather also means that ticks become more active and this can agent by feeding as larvae on certain rodent species. increase the risk of a tick-borne disease. The tick-borne dis- In the fall, the nymphs become adults and infected nymphs eases that occur most often in Virginia are Lyme disease, become infected adults. Adult blacklegged ticks prefer to feed Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and ehrlichiosis. on deer. However, adult ticks will occasionally bite people on warm days of the fall and winter and can transmit Lyme disease Lyme Disease at that time. Lyme disease is caused by infection with a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi. The number of Lyme disease cases Transmission of Lyme disease by the nymph or adult ticks reported in Virginia has increased substantially in recent years. does not occur until the tick has been attached and feeding on a human or animal host for at least 36 hours. The Tick The blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis), formerly known as The Symptoms the deer tick, is the only carrier of Lyme disease in the Eastern Between three days to several weeks after being bitten by an U.S. The blacklegged tick's name comes from it being the only infected tick, 70-90% of people develop a circular or oval rash, tick in the Eastern U.S. that bites humans and has legs that are called erythema migrans (or EM), at the site of the bite. -

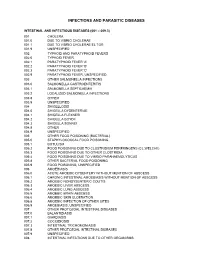

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

Reportable Disease Surveillance in Virginia, 2013

Reportable Disease Surveillance in Virginia, 2013 Marissa J. Levine, MD, MPH State Health Commissioner Report Production Team: Division of Surveillance and Investigation, Division of Disease Prevention, Division of Environmental Epidemiology, and Division of Immunization Virginia Department of Health Post Office Box 2448 Richmond, Virginia 23218 www.vdh.virginia.gov ACKNOWLEDGEMENT In addition to the employees of the work units listed below, the Office of Epidemiology would like to acknowledge the contributions of all those engaged in disease surveillance and control activities across the state throughout the year. We appreciate the commitment to public health of all epidemiology staff in local and district health departments and the Regional and Central Offices, as well as the conscientious work of nurses, environmental health specialists, infection preventionists, physicians, laboratory staff, and administrators. These persons report or manage disease surveillance data on an ongoing basis and diligently strive to control morbidity in Virginia. This report would not be possible without the efforts of all those who collect and follow up on morbidity reports. Divisions in the Virginia Department of Health Office of Epidemiology Disease Prevention Telephone: 804-864-7964 Environmental Epidemiology Telephone: 804-864-8182 Immunization Telephone: 804-864-8055 Surveillance and Investigation Telephone: 804-864-8141 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 -

CD Alert Monthly Newsletter of National Centre for Disease Control, Directorate General of Health Services, Government of India

CD Alert Monthly Newsletter of National Centre for Disease Control, Directorate General of Health Services, Government of India May - July 2009 Vol. 13 : No. 1 SCRUB TYPHUS & OTHER RICKETTSIOSES it lacks lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan RICKETTSIAL DISEASES and does not have an outer slime layer. It is These are the diseases caused by rickettsiae endowed with a major surface protein (56kDa) which are small, gram negative bacilli adapted and some minor surface protein (110, 80, 46, to obligate intracellular parasitism, and 43, 39, 35, 25 and 25kDa). There are transmitted by arthropod vectors. These considerable differences in virulence and organisms are primarily parasites of arthropods antigen composition among individual strains such as lice, fleas, ticks and mites, in which of O.tsutsugamushi. O.tsutsugamushi has they are found in the alimentary canal. In many serotypes (Karp, Gillian, Kato and vertebrates, including humans, they infect the Kawazaki). vascular endothelium and reticuloendothelial GLOBAL SCENARIO cells. Commonly known rickettsial disease is Scrub Typhus. Geographic distribution of the disease occurs within an area of about 13 million km2 including- The family Rickettsiaeceae currently comprises Afghanistan and Pakistan to the west; Russia of three genera – Rickettsia, Orientia and to the north; Korea and Japan to the northeast; Ehrlichia which appear to have descended Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and northern from a common ancestor. Former members Australia to the south; and some smaller of the family, Coxiella burnetii, which causes islands in the western Pacific. It was Q fever and Rochalimaea quintana causing first observed in Japan where it was found to trench fever have been excluded because the be transmitted by mites. -

Lyme Disease Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Tick Paralysis Haemobartonellosis Tularemia Ehrlichiosis Anaplasmosis

Fall is the beginning of tick season in our area. However, you can find ticks all year round if you like to hike or camp in the woods, or other type of outdoor activities. Ticks are not as easy to kill as fleas, but there are several different ways to control ticks from oral to topical medications and well as collars. If you find a tick embedded in your pet and you choose to try and remove it, be aware that you can accidentally leave the head behind. This can cause a local irritation even possibly an infection. We will be happy to assist with removing a tick for you to help prevent any problems. Protecting your cat or dog (or both) from ticks is an important part of disease prevention. In fact, there are several diseases that can be transmitted to your pet from a tick bite. Some of the most common tick-borne diseases seen in the Western United States are: Lyme Disease Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Tick Paralysis Haemobartonellosis Tularemia Ehrlichiosis Anaplasmosis Lyme Disease Also called borreliosis, Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. Deer ticks carry these bacteria, transmitting them to the animal while sucking its blood. The tick must be attached to the dog (or cat) for about 48 hours in order to transmit the bacteria to the animal's bloodstream. If the tick is removed before this, transmission will usually not occur. Common signs of Lyme disease include lameness, fever, swollen lymph nodes and joints, and a reduced appetite. In severe cases, animals may develop kidney disease, heart conditions, or nervous system disorders. -

Melioidosis in Northern Tanzania: an Important Cause of Febrile Illness?

Melioidosis and serological evidence of exposure to Burkholderia pseudomallei among patients with fever, northern Tanzania Michael Maze Department of Medicine University of Otago, Christchurch Melioidosis Melioidosis caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei • Challenging to identify when cultured Soil reservoir, with human infection from contact with contaminated water Most infected people are asymptomatic: 1 clinical illness for 4,500 antibody producing exposures Febrile illness with a variety of presentations and bacteraemia is present in 40-60% of people with acute illness Estimated 89,000 deaths globally Gavin Koh CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4975784 Laboratory diagnosis of febrile inpatients, northern Tanzania, 2007-8 (n=870) Malaria (1.6%) Bacteremia (9.8%) Mycobacteremia (1.6%) Fungemia (2.9%) Brucellosis (3.5%) Leptospirosis (8.8%) Q fever (5.0%) No diagnosis (50.1%) Spotted fever group rickettsiosis (8.0%) Typhus group rickettsiosis (0.4%) Chikungunya (7.9%) Crump PLoS Neglect Trop Dis 2013; 7: e2324 Predicted environmental suitability for B. pseudomallei in East Africa Large areas of Africa are predicted to be highly suitable for Burkholderia pseudomallei East Africa is less suitable but pockets of higher suitability including northern Tanzania Northern Tanzania Increasing suitability for B. pseudomallei Limmathurotsakul Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(1). Melioidosis epidemiology in Africa Paucity of empiric data • Scattered case reports • Report from Kilifi, Kenya identified 4 bacteraemic cases from 66,000 patients who had blood cultured1 • 5.9% seroprevalence among healthy adults in Uganda2 • No reports from Tanzania 1. Limmathurotsakul Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(1). 2. Frazer J R Army Med Corps. 1982;128(3):123-30. -

WO 2013/042140 A4 28 March 2013 (28.03.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/042140 A4 28 March 2013 (28.03.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, A61K 31/197 (2006.01) A61K 45/06 (2006.01) RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, A61K 31/60 (2006.01) A61P 31/00 (2006.01) TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, A61K 33/22 (2006.01) ZM, ZW. (21) International Application Number: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every PCT/IN20 12/000634 kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (22) International Filing Date UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 24 September 2012 (24.09.2012) TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, (25) Filing Language: English EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, (26) Publication Language: English TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, (30) Priority Data: ML, MR, NE, SN, TD, TG). 2792/DEL/201 1 23 September 201 1 (23.09.201 1) IN Declarations under Rule 4.17 : (72) Inventor; and — of inventorship (Rule 4.17(iv)) (71) Applicant : CHAUDHARY, Manu [IN/IN]; 51-52, In dustrial Area Phase- 1, Panchkula 1341 13 (IN). -

Typhus Fever, Organism Inapparently

Rickettsia Importance Rickettsia prowazekii is a prokaryotic organism that is primarily maintained in prowazekii human populations, and spreads between people via human body lice. Infected people develop an acute, mild to severe illness that is sometimes complicated by neurological Infections signs, shock, gangrene of the fingers and toes, and other serious signs. Approximately 10-30% of untreated clinical cases are fatal, with even higher mortality rates in Epidemic typhus, debilitated populations and the elderly. People who recover can continue to harbor the Typhus fever, organism inapparently. It may re-emerge years later and cause a similar, though Louse–borne typhus fever, generally milder, illness called Brill-Zinsser disease. At one time, R. prowazekii Typhus exanthematicus, regularly caused extensive outbreaks, killing thousands or even millions of people. This gave rise to the most common name for the disease, epidemic typhus. Epidemic typhus Classical typhus fever, no longer occurs in developed countries, except as a sporadic illness in people who Sylvatic typhus, have acquired it while traveling, or who have carried the organism for years without European typhus, clinical signs. In North America, R. prowazekii is also maintained in southern flying Brill–Zinsser disease, Jail fever squirrels (Glaucomys volans), resulting in sporadic zoonotic cases. However, serious outbreaks still occur in some resource-poor countries, especially where people are in close contact under conditions of poor hygiene. Epidemics have the potential to emerge anywhere social conditions disintegrate and human body lice spread unchecked. Last Updated: February 2017 Etiology Rickettsia prowazekii is a pleomorphic, obligate intracellular, Gram negative coccobacillus in the family Rickettsiaceae and order Rickettsiales of the α- Proteobacteria. -

Leptospirosis and Coinfection: Should We Be Concerned?

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Leptospirosis and Coinfection: Should We Be Concerned? Asmalia Md-Lasim 1,2, Farah Shafawati Mohd-Taib 1,* , Mardani Abdul-Halim 3 , Ahmad Mohiddin Mohd-Ngesom 4 , Sheila Nathan 1 and Shukor Md-Nor 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, UKM, Bangi 43600, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.M.-L.); [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (S.M.-N.) 2 Herbal Medicine Research Centre (HMRC), Institute for Medical Research (IMR), National Institue of Health (NIH), Ministry of Health, Shah Alam 40170, Selangor, Malaysia 3 Biotechnology Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, Kota Kinabalu 88400, Sabah, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 Center for Toxicology and Health Risk, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur 50300, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +60-12-3807701 Abstract: Pathogenic Leptospira is the causative agent of leptospirosis, an emerging zoonotic disease affecting animals and humans worldwide. The risk of host infection following interaction with environmental sources depends on the ability of Leptospira to persist, survive, and infect the new host to continue the transmission chain. Leptospira may coexist with other pathogens, thus providing a suitable condition for the development of other pathogens, resulting in multi-pathogen infection in humans. Therefore, it is important to better understand the dynamics of transmission by these pathogens. We conducted Boolean searches of several databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Citation: Md-Lasim, A.; Mohd-Taib, SciELO, and ScienceDirect, to identify relevant published data on Leptospira and coinfection with F.S.; Abdul-Halim, M.; Mohd-Ngesom, other pathogenic bacteria. -

What Do We Know About Q Fever in Mexico?

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL What do we know about Q fever in Mexico? Javier Araujo-Meléndez,* José Sifuentes-Osornio,* J. Miriam Bobadilla-del-Valle,* Antonio Aguilar-Cruz,** Orestes Torres-Ángeles,** José L. Ramírez-González,*** Alfredo Ponce-de-León,* Guillermo M. Ruiz-Palacios,* M. Lourdes Guerrero-Almeida* * Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán. ** Jurisdicción Sanitaria No. 4, Huichapan, Hidalgo. *** Hospital General, Huichapan, Hidalgo. ABSTRACT ¿Qué sabemos acerca de la fiebre Q en México? In Mexico, Q fever is considered a rare disease among hu- RESUMEN mans and animals. From March to May of 2008, three pa- tients were referred, from the state of Hidalgo to a En México la fiebre Q se considera una enfermedad rara en- tertiary-care center in Mexico City, with an acute febrile ill- tre los humanos y los animales. Sin embargo, entre marzo y ness that was diagnosed as Q fever. We decided to undertake a mayo 2008 tres pacientes del estado de Hidalgo fueron refe- cross sectional pilot study to identify cases of acute disease in ridos a un hospital de tercer nivel en la Ciudad de México this particular region and to determine the seroprevalence of por una enfermedad febril aguda y fueron diagnosticados Coxiella burnetii among healthy individuals with known risk con fiebre Q. Se decidió llevar a cabo un estudio piloto para factors for infection with this bacteria. Q fever was defined identificar casos de enfermedad aguda en esa región y deter- according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention minar la prevalencia serológica de Coxiella burnetii en indi- criteria.