Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Analysis of Microbial Sharing and Specialization in A

Downloaded from http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 15, 2017 Community analysis of microbial sharing rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org and specialization in a Costa Rican ant–plant–hemipteran symbiosis Elizabeth G. Pringle1,2 and Corrie S. Moreau3 Research 1Department of Biology, Program in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology, University of Nevada, Cite this article: Pringle EG, Moreau CS. 2017 Reno, NV 89557, USA 2Michigan Society of Fellows, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA Community analysis of microbial sharing and 3Department of Science and Education, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, specialization in a Costa Rican ant–plant– Chicago, IL 60605, USA hemipteran symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B 284: EGP, 0000-0002-4398-9272 20162770. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2770 Ants have long been renowned for their intimate mutualisms with tropho- bionts and plants and more recently appreciated for their widespread and diverse interactions with microbes. An open question in symbiosis research is the extent to which environmental influence, including the exchange of Received: 14 December 2016 microbes between interacting macroorganisms, affects the composition and Accepted: 17 January 2017 function of symbiotic microbial communities. Here we approached this ques- tion by investigating symbiosis within symbiosis. Ant–plant–hemipteran symbioses are hallmarks of tropical ecosystems that produce persistent close contact among the macroorganism partners, which then have substantial opportunity to exchange symbiotic microbes. We used metabarcoding and Subject Category: quantitative PCR to examine community structure of both bacteria and Ecology fungi in a Neotropical ant–plant–scale-insect symbiosis. Both phloem-feed- ing scale insects and honeydew-feeding ants make use of microbial Subject Areas: symbionts to subsist on phloem-derived diets of suboptimal nutritional qual- ecology, evolution, microbiology ity. -

Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia

pathogens Article Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia Species in Amblyomma albolimbatum Ticks from the Shingleback Skink (Tiliqua rugosa) in Southern Western Australia Mythili Tadepalli 1, Gemma Vincent 1, Sze Fui Hii 1, Simon Watharow 2, Stephen Graves 1,3 and John Stenos 1,* 1 Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory, University Hospital Geelong, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (G.V.); [email protected] (S.F.H.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Reptile Victoria Inc., Melbourne 3035, Australia; [email protected] 3 Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Nepean Hospital, NSW Health Pathology, Penrith 2747, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tick-borne infectious diseases caused by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Rick- ettsia are a growing global problem to human and animal health. Surveillance of these pathogens at the wildlife interface is critical to informing public health strategies to limit their impact. In Australia, reptile-associated ticks such as Bothriocroton hydrosauri are the reservoirs for Rickettsia honei, the causative agent of Flinders Island spotted fever. In an effort to gain further insight into the potential for reptile-associated ticks to act as reservoirs for rickettsial infection, Rickettsia-specific PCR screening was performed on 64 Ambylomma albolimbatum ticks taken from shingleback skinks (Tiliqua rugosa) lo- cated in southern Western Australia. PCR screening revealed 92% positivity for rickettsial DNA. PCR Citation: Tadepalli, M.; Vincent, G.; amplification and sequencing of phylogenetically informative rickettsial genes (ompA, ompB, gltA, Hii, S.F.; Watharow, S.; Graves, S.; Stenos, J. -

(Batch Learning Self-Organizing Maps), to the Microbiome Analysis of Ticks

Title A novel approach, based on BLSOMs (Batch Learning Self-Organizing Maps), to the microbiome analysis of ticks Nakao, Ryo; Abe, Takashi; Nijhof, Ard M; Yamamoto, Seigo; Jongejan, Frans; Ikemura, Toshimichi; Sugimoto, Author(s) Chihiro The ISME Journal, 7(5), 1003-1015 Citation https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.171 Issue Date 2013-03 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/53167 Type article (author version) File Information ISME_Nakao.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP A novel approach, based on BLSOMs (Batch Learning Self-Organizing Maps), to the microbiome analysis of ticks Ryo Nakao1,a, Takashi Abe2,3,a, Ard M. Nijhof4, Seigo Yamamoto5, Frans Jongejan6,7, Toshimichi Ikemura2, Chihiro Sugimoto1 1Division of Collaboration and Education, Research Center for Zoonosis Control, Hokkaido University, Kita-20, Nishi-10, Kita-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido 001-0020, Japan 2Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology, Nagahama, Shiga 526-0829, Japan 3Graduate School of Science & Technology, Niigata University, 8050, Igarashi 2-no-cho, Nishi- ku, Niigata 950-2181, Japan 4Institute for Parasitology and Tropical Veterinary Medicine, Freie Universität Berlin, Königsweg 67, 14163 Berlin, Germany 5Miyazaki Prefectural Institute for Public Health and Environment, 2-3-2 Gakuen Kibanadai Nishi, Miyazaki 889-2155, Japan 6Utrecht Centre for Tick-borne Diseases (UCTD), Department of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University, Yalelaan 1, 3584 CL Utrecht, The Netherlands 7Department of Veterinary Tropical Diseases, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X04, 0110 Onderstepoort, South Africa aThese authors contributed equally to this work. Keywords: BLSOMs/emerging diseases/metagenomics/microbiomes/symbionts/ticks Running title: Tick microbiomes revealed by BLSOMs Subject category: Microbe-microbe and microbe-host interactions Abstract Ticks transmit a variety of viral, bacterial and protozoal pathogens, which are often zoonotic. -

Characterization of the Interaction Between R. Conorii and Human

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 4-5-2018 Characterization of the Interaction Between R. Conorii and Human Host Vitronectin in Rickettsial Pathogenesis Abigail Inez Fish Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Bacteria Commons, Bacteriology Commons, Biology Commons, Immunology of Infectious Disease Commons, and the Pathogenic Microbiology Commons Recommended Citation Fish, Abigail Inez, "Characterization of the Interaction Between R. Conorii and Human Host Vitronectin in Rickettsial Pathogenesis" (2018). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4566. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4566 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN R. CONORII AND HUMAN HOST VITRONECTIN IN RICKETTSIAL PATHOGENESIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Interdepartmental Program in Biomedical and Veterinary Medical Sciences Through the Department of Pathobiological Sciences by Abigail Inez -

Genetic Diversity of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals in the Qaidam

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China Huaxiang Rao1, Shoujiang Li3, Liang Lu4, Rong Wang3, Xiuping Song4, Kai Sun5, Yan Shi3, Dongmei Li4* & Juan Yu2* Investigation of the prevalence and diversity of Bartonella infections in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China, could provide a scientifc basis for the control and prevention of Bartonella infections in humans. Accordingly, in this study, small mammals were captured using snap traps in Wulan County and Ge’ermu City, Qaidam Basin, China. Spleen and brain tissues were collected and cultured to isolate Bartonella strains. The suspected positive colonies were detected with polymerase chain reaction amplifcation and sequencing of gltA, ftsZ, RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) and ribC genes. Among 101 small mammals, 39 were positive for Bartonella, with the infection rate of 38.61%. The infection rate in diferent tissues (spleens and brains) (χ2 = 0.112, P = 0.738) and gender (χ2 = 1.927, P = 0.165) of small mammals did not have statistical diference, but that in diferent habitats had statistical diference (χ2 = 10.361, P = 0.016). Through genetic evolution analysis, 40 Bartonella strains were identifed (two diferent Bartonella species were detected in one small mammal), including B. grahamii (30), B. jaculi (3), B. krasnovii (3) and Candidatus B. gerbillinarum (4), which showed rodent-specifc characteristics. B. grahamii was the dominant epidemic strain (accounted for 75.0%). Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis showed that B. grahamii in the Qaidam Basin, might be close to the strains isolated from Japan and China. -

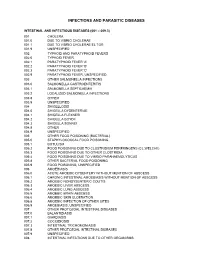

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

“Candidatus Deianiraea Vastatrix” with the Ciliate Paramecium Suggests

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/479196; this version posted November 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The extracellular association of the bacterium “Candidatus Deianiraea vastatrix” with the ciliate Paramecium suggests an alternative scenario for the evolution of Rickettsiales 5 Castelli M.1, Sabaneyeva E.2, Lanzoni O.3, Lebedeva N.4, Floriano A.M.5, Gaiarsa S.5,6, Benken K.7, Modeo L. 3, Bandi C.1, Potekhin A.8, Sassera D.5*, Petroni G.3* 1. Centro Romeo ed Enrica Invernizzi Ricerca Pediatrica, Dipartimento di Bioscienze, Università 10 degli studi di Milano, Milan, Italy 2. Department of Cytology and Histology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia 3. Dipartimento di Biologia, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy 4 Centre of Core Facilities “Culture Collections of Microorganisms”, Saint Petersburg State 15 University, Saint Petersburg, Russia 5. Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie, Università degli studi di Pavia, Pavia, Italy 6. UOC Microbiologia e Virologia, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy 7. Core Facility Center for Microscopy and Microanalysis, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint- Petersburg, Russia 20 8. Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint- Petersburg, Russia * Corresponding authors, contacts: [email protected] ; [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/479196; this version posted November 27, 2018. -

Evolutionary Origin of Insect–Wolbachia Nutritional Mutualism

Evolutionary origin of insect–Wolbachia nutritional mutualism Naruo Nikoha,1, Takahiro Hosokawab,1, Minoru Moriyamab,1, Kenshiro Oshimac, Masahira Hattoric, and Takema Fukatsub,2 aDepartment of Liberal Arts, The Open University of Japan, Chiba 261-8586, Japan; bBioproduction Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Tsukuba 305-8566, Japan; and cCenter for Omics and Bioinformatics, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, University of Tokyo, Kashiwa 277-8561, Japan Edited by Nancy A. Moran, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved June 3, 2014 (received for review May 20, 2014) Obligate insect–bacterium nutritional mutualism is among the insects, generally conferring negative fitness consequences to most sophisticated forms of symbiosis, wherein the host and the their hosts and often causing hosts’ reproductive aberrations to symbiont are integrated into a coherent biological entity and un- enhance their own transmission in a selfish manner (7, 8). Re- able to survive without the partnership. Originally, however, such cently, however, a Wolbachia strain associated with the bedbug obligate symbiotic bacteria must have been derived from free-living Cimex lectularius,designatedaswCle, was shown to be es- bacteria. How highly specialized obligate mutualisms have arisen sential for normal growth and reproduction of the blood- from less specialized associations is of interest. Here we address this sucking insect host via provisioning of B vitamins (9). Hence, it –Wolbachia evolutionary -

Fleas and Flea-Borne Diseases

International Journal of Infectious Diseases 14 (2010) e667–e676 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Review Fleas and flea-borne diseases Idir Bitam a, Katharina Dittmar b, Philippe Parola a, Michael F. Whiting c, Didier Raoult a,* a Unite´ de Recherche en Maladies Infectieuses Tropicales Emergentes, CNRS-IRD UMR 6236, Faculte´ de Me´decine, Universite´ de la Me´diterrane´e, 27 Bd Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille Cedex 5, France b Department of Biological Sciences, SUNY at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA c Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA ARTICLE INFO SUMMARY Article history: Flea-borne infections are emerging or re-emerging throughout the world, and their incidence is on the Received 3 February 2009 rise. Furthermore, their distribution and that of their vectors is shifting and expanding. This publication Received in revised form 2 June 2009 reviews general flea biology and the distribution of the flea-borne diseases of public health importance Accepted 4 November 2009 throughout the world, their principal flea vectors, and the extent of their public health burden. Such an Corresponding Editor: William Cameron, overall review is necessary to understand the importance of this group of infections and the resources Ottawa, Canada that must be allocated to their control by public health authorities to ensure their timely diagnosis and treatment. Keywords: ß 2010 International Society for Infectious Diseases. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Flea Siphonaptera Plague Yersinia pestis Rickettsia Bartonella Introduction to 16 families and 238 genera have been described, but only a minority is synanthropic, that is they live in close association with The past decades have seen a dramatic change in the geographic humans (Table 1).4,5 and host ranges of many vector-borne pathogens, and their diseases. -

Bartonella Henselae • Fleas and Black-Legged Ticks (Also Called Deer Ticks) of the Genus Ixodes May Serve As Vectors, but This Has Not Disease Agent: Been Proven

APPENDIX 2 Bartonella henselae • Fleas and black-legged ticks (also called deer ticks) of the genus Ixodes may serve as vectors, but this has not Disease Agent: been proven. • Bartonella henselae Blood Phase: Disease Agent Characteristics: • Agent found in endothelial cells and associated with RBCs in symptomatic cases • Gram-negative bacillus or coccobacillus, aerobic, • Occult bacteremia sometimes occurs in the absence nonmotile, nonspore-forming, facultatively intracel- of specific antibodies. lular bacterium • Order: Rhizobiales; Family: Bartonellaceae Survival/Persistence in Blood Products: • Size: 0.3-0.6 ¥ 0.3-1.0 mm • Nucleic acid: Approximately 1900 kb of DNA • A spiking study suggests that B. henselae added to RBCs can be recovered on solid media through 35 Disease Name: days of storage at 4°C. • Cat scratch disease • Cat scratch fever Transmission by Blood Transfusion: • Bacillary angiomatosis • Theoretical • Bacillary peliosis Cases/Frequency in Population: Priority Level: • 22,000 cases per year estimated in the US • Scientific/Epidemiologic evidence regarding blood • 2-6% in US blood donors safety: Theoretical • Cumulative seroprevalence of 7.1% to B. henselae and • Public perception and/or regulatory concern regard- B. quintana in US veterinary professionals ing blood safety: Absent • Public concern regarding disease agent: Very low Incubation Period: Background: • 3-10 days to appearance of papule at inoculation site; regional adenopathy may follow after a few weeks • In 1909,ALBartondescribed organisms that adhered to RBCs. Likelihood of Clinical Disease: • The name Bartonella bacilliformis was used for the • Relatively benign and self-limiting, lasting 6-12 weeks only member of the group identified before 1993. in the absence of antibiotic therapy • Several other species of Bartonella are known to infect humans, but at present, B. -

(Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) and the Bat Soft Tick Argas Vespe

Zhao et al. Parasites Vectors (2020) 13:10 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-3885-x Parasites & Vectors SHORT REPORT Open Access Rickettsiae in the common pipistrelle Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) and the bat soft tick Argas vespertilionis (Ixodida: Argasidae) Shuo Zhao1†, Meihua Yang2†, Gang Liu1†, Sándor Hornok3, Shanshan Zhao1, Chunli Sang1, Wenbo Tan1 and Yuanzhi Wang1* Abstract Background: Increasing molecular evidence supports that bats and/or their ectoparasites may harbor vector-borne bacteria, such as bartonellae and borreliae. However, the simultaneous occurrence of rickettsiae in bats and bat ticks has been poorly studied. Methods: In this study, 54 bat carcasses and their infesting soft ticks (n 67) were collected in Shihezi City, north- western China. The heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, small intestine and large= intestine of bats were dissected, followed by DNA extraction. Soft ticks were identifed both morphologically and molecularly. All samples were examined for the presence of rickettsiae by amplifying four genetic markers (17-kDa, gltA, ompA and ompB). Results: All bats were identifed as Pipistrellus pipistrellus, and their ticks as Argas vespertilionis. Molecular analyses showed that DNA of Rickettsia parkeri, R. lusitaniae, R. slovaca and R. raoultii was present in bat organs/tissues. In addition, nine of the 67 bat soft ticks (13.43%) were positive for R. raoultii (n 5) and R. rickettsii (n 4). In the phylo- genetic analysis, these bat-associated rickettsiae clustered together with conspecifc= sequences reported= from other host and tick species, confrming the above results. Conclusions: To the best of our knowledge, DNA of R. parkeri, R. slovaca and R. -

Genome Project Reveals a Putative Rickettsial Endosymbiont

GBE Bacterial DNA Sifted from the Trichoplax adhaerens (Animalia: Placozoa) Genome Project Reveals a Putative Rickettsial Endosymbiont Timothy Driscoll1,y, Joseph J. Gillespie1,2,*,y, Eric K. Nordberg1,AbduF.Azad2, and Bruno W. Sobral1,3 1Virginia Bioinformatics Institute at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University 2Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Maryland School of Medicine 3Present address: Nestle´ Institute of Health Sciences SA, Campus EPFL, Quartier de L’innovation, Lausanne, Switzerland *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. yThese authors contributed equally to this work. Accepted: March 1, 2013 Abstract Eukaryotic genome sequencing projects often yield bacterial DNA sequences, data typically considered as microbial contamination. However, these sequences may also indicate either symbiont genes or lateral gene transfer (LGT) to host genomes. These bacterial sequences can provide clues about eukaryote–microbe interactions. Here, we used the genome of the primitive animal Trichoplax adhaerens (Metazoa: Placozoa), which is known to harbor an uncharacterized Gram-negative endosymbiont, to search for the presence of bacterial DNA sequences. Bioinformatic and phylogenomic analyses of extracted data from the genome assembly (181 bacterial coding sequences [CDS]) and trace read archive (16S rDNA) revealed a dominant proteobacterial profile strongly skewed to Rickettsiales (Alphaproteobacteria) genomes. By way of phylogenetic analysis of 16S rDNA and 113 proteins conserved across proteobacterial genomes, as well as identification of 27 rickettsial signature genes, we propose a Rickettsiales endosymbiont of T. adhaerens (RETA). The majority (93%) of the identified bacterial CDS belongs to small scaffolds containing prokaryotic-like genes; however, 12 CDS were identified on large scaffolds comprised of eukaryotic-like genes, suggesting that T.