Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proteus Vulgaris

48 Monte Carlo Crescent Kyalami Business Park Kyalami, Johannesburg, 1684, RSA Tel: +27 (0)11 463 3260 Fax: + 27 (0)86 557 2232 Email: [email protected] www.thistle.co.za Please read this section first The HPCSA and the Med Tech Society have confirmed that this clinical case study, plus your routine review of your EQA reports from Thistle QA, should be documented as a “Journal Club” activity. This means that you must record those attending for CEU purposes. Thistle will not issue a certificate to cover these activities, nor send out “correct” answers to the CEU questions at the end of this case study. The Thistle QA CEU No is: MT- 16/009 Each attendee should claim THREE CEU points for completing this Quality Control Journal Club exercise, and retain a copy of the relevant Thistle QA Participation Certificate as proof of registration on a Thistle QA EQA. MICROBIOLOGY LEGEND CYCLE 41 ORGANISM 3 Proteus Vulgaris Proteus Vulgaris is a rod shaped Gram-Negative chemoheterotrophic bacterium. The size of the individual cells varies from 0.4 to 0.6 micrometers by 1.2 to 2.5 micrometers. P. vulgaris possesses peritrichous flagella, making it actively motile. It inhabits the soil, polluted water, raw meat, gastrointestinal tracts of animals and dust. In humans, Proteus species most frequently cause urinary tract infections, but can also produce severe abscesses and is widely associated with nosocomial infections. Isolation of Organism With basic microbiological technique, samples believed to contain P. vulgaris are first incubated on nutrient agar to form colonies. To test the Gram-Negative and oxidase-negative characteristics of Enterobacteriaceae, Gram stains and oxidase tests are performed. -

Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia

pathogens Article Molecular Evidence of Novel Spotted Fever Group Rickettsia Species in Amblyomma albolimbatum Ticks from the Shingleback Skink (Tiliqua rugosa) in Southern Western Australia Mythili Tadepalli 1, Gemma Vincent 1, Sze Fui Hii 1, Simon Watharow 2, Stephen Graves 1,3 and John Stenos 1,* 1 Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory, University Hospital Geelong, Geelong 3220, Australia; [email protected] (M.T.); [email protected] (G.V.); [email protected] (S.F.H.); [email protected] (S.G.) 2 Reptile Victoria Inc., Melbourne 3035, Australia; [email protected] 3 Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Nepean Hospital, NSW Health Pathology, Penrith 2747, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Tick-borne infectious diseases caused by obligate intracellular bacteria of the genus Rick- ettsia are a growing global problem to human and animal health. Surveillance of these pathogens at the wildlife interface is critical to informing public health strategies to limit their impact. In Australia, reptile-associated ticks such as Bothriocroton hydrosauri are the reservoirs for Rickettsia honei, the causative agent of Flinders Island spotted fever. In an effort to gain further insight into the potential for reptile-associated ticks to act as reservoirs for rickettsial infection, Rickettsia-specific PCR screening was performed on 64 Ambylomma albolimbatum ticks taken from shingleback skinks (Tiliqua rugosa) lo- cated in southern Western Australia. PCR screening revealed 92% positivity for rickettsial DNA. PCR Citation: Tadepalli, M.; Vincent, G.; amplification and sequencing of phylogenetically informative rickettsial genes (ompA, ompB, gltA, Hii, S.F.; Watharow, S.; Graves, S.; Stenos, J. -

Distribution of Tick-Borne Diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2*

Wu et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:119 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/119 REVIEW Open Access Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China Xian-Bo Wu1, Ren-Hua Na2, Shan-Shan Wei2, Jin-Song Zhu3 and Hong-Juan Peng2* Abstract As an important contributor to vector-borne diseases in China, in recent years, tick-borne diseases have attracted much attention because of their increasing incidence and consequent significant harm to livestock and human health. The most commonly observed human tick-borne diseases in China include Lyme borreliosis (known as Lyme disease in China), tick-borne encephalitis (known as Forest encephalitis in China), Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (known as Xinjiang hemorrhagic fever in China), Q-fever, tularemia and North-Asia tick-borne spotted fever. In recent years, some emerging tick-borne diseases, such as human monocytic ehrlichiosis, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and a novel bunyavirus infection, have been reported frequently in China. Other tick-borne diseases that are not as frequently reported in China include Colorado fever, oriental spotted fever and piroplasmosis. Detailed information regarding the history, characteristics, and current epidemic status of these human tick-borne diseases in China will be reviewed in this paper. It is clear that greater efforts in government management and research are required for the prevention, control, diagnosis, and treatment of tick-borne diseases, as well as for the control of ticks, in order to decrease the tick-borne disease burden in China. Keywords: Ticks, Tick-borne diseases, Epidemic, China Review (Table 1) [2,4]. Continuous reports of emerging tick-borne Ticks can carry and transmit viruses, bacteria, rickettsia, disease cases in Shandong, Henan, Hebei, Anhui, and spirochetes, protozoans, Chlamydia, Mycoplasma,Bartonia other provinces demonstrate the rise of these diseases bodies, and nematodes [1,2]. -

Vectorborne Zoonoses: Break-Out Session Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Workshop – Oct

Texas Department of State Health Services Vectorborne Zoonoses: Break-out Session Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Workshop – Oct. 2018 DSHS Zoonosis Control Branch Session Topics Texas Department of State Health Services • NEDSS case investigation tips • Lyme disease • Rickettsial diseases • Arboviral diseases ELC 2018 - Vectorborne Diseases 2 Texas Department of State Health Services Don’t be a Reject! Helpful tips to keep your notification from being rejected ELC breakout session October 3, 2018 Kamesha Owens, MPH Zoonosis Control Branch Texas Department of State Health Services Objectives • Rejection Criteria • How to document in NBS (NEDSS) • How to Report Texas Department of State Health Services 10/3/2018 ELC 2018 - Vectorborne Diseases 4 Rejection Criteria Texas Department of State Health Services Missing/incorrect information: • Incorrect case status or condition selected • Full Name • Date of Birth • Address • County • Missing laboratory data 10/3/2018 ELC 2018 - Vectorborne Diseases 5 Rejection Criteria continued Texas Department of State Health Services • Inconsistent information • e.g. Report date is a week before onset date • Case investigation form not received by ZCB within 14 days of notification • ZCB recommends that notification not be created until the case is closed and the investigation form has been submitted 10/3/2018 ELC 2018 - Vectorborne Diseases 6 Rejection Criteria continued Texas Department of State Health Services • Condition-specific information necessary to report the case is missing: • Travel history for Zika and other non-endemic conditions • Evidence of neurological disease for WNND case • Supporting documentation for Lyme disease case determination 10/3/2018 ELC 2018 - Vectorborne Diseases 7 How to Document in NBS (NEDSS) Do Don’t Add detailed comments in designated Leave us guessing! comments box under case info tab. -

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis What is ehrlichiosis and can also have a wide range of signs Who should I contact, if I what causes it? including loss of appetite, weight suspect ehrlichiosis? Ehrlichiosis (air-lick-ee-OH-sis) is a loss, prolonged fever, weakness, and In Animals – group of similar diseases caused by bleeding disorders. Contact your veterinarian. In Humans – several different bacteria that attack Can I get ehrlichiosis? the body’s white blood cells (cells Contact your physician. Yes. People can become infected involved in the immune system that with ehrlichiosis if they are bitten by How can I protect my animal help protect against disease). The an infected tick (vector). The disease organisms that cause ehrlichiosis are from ehrlichiosis? is not spread by direct contact with found throughout the world and are Ehrlichiosis is best prevented by infected animals. However, animals spread by infected ticks. Symptoms in controlling ticks. Inspect your pet can be carriers of ticks with the animals and humans can range from frequently for the presence of ticks bacteria and bring them into contact mild, flu-like illness (fever, body aches) and remove them promptly if found. with humans. Ehrlichiosis can also to severe, possibly fatal disease. Contact your veterinarian for effective be transmitted through blood tick control products to use on What animals get transfusions, but this is rare. your animal. ehrlichiosis? Disease in humans varies from How can I protect myself Many animals can be affected by mild infection to severe, possibly fatal ehrlichiosis, although the specific infection. Symptoms may include from ehrlichiosis? bacteria involved may vary with the flu-like signs (chills, body aches and The risk for infection is decreased animal species. -

Babela Massiliensis, a Representative of a Widespread Bacterial

Babela massiliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae Isabelle Pagnier, Natalya Yutin, Olivier Croce, Kira S Makarova, Yuri I Wolf, Samia Benamar, Didier Raoult, Eugene V. Koonin, Bernard La Scola To cite this version: Isabelle Pagnier, Natalya Yutin, Olivier Croce, Kira S Makarova, Yuri I Wolf, et al.. Babela mas- siliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae. Biology Direct, BioMed Central, 2015, 10 (13), 10.1186/s13062-015-0043-z. hal-01217089 HAL Id: hal-01217089 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01217089 Submitted on 19 Oct 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pagnier et al. Biology Direct (2015) 10:13 DOI 10.1186/s13062-015-0043-z RESEARCH Open Access Babela massiliensis, a representative of a widespread bacterial phylum with unusual adaptations to parasitism in amoebae Isabelle Pagnier1, Natalya Yutin2, Olivier Croce1, Kira S Makarova2, Yuri I Wolf2, Samia Benamar1, Didier Raoult1, Eugene V Koonin2 and Bernard La Scola1* Abstract Background: Only a small fraction of bacteria and archaea that are identifiable by metagenomics can be grown on standard media. -

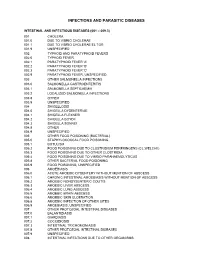

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Uncommon Pathogens Causing Hospital-Acquired Infections in Postoperative Cardiac Surgical Patients

Published online: 2020-03-06 THIEME Review Article 89 Uncommon Pathogens Causing Hospital-Acquired Infections in Postoperative Cardiac Surgical Patients Manoj Kumar Sahu1 Netto George2 Neha Rastogi2 Chalatti Bipin1 Sarvesh Pal Singh1 1Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, CN Centre, All Address for correspondence Manoj K Sahu, MD, DNB, Department India Institute of Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, India of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, CTVS office, 7th floor, CN 2Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi-110029, Medical Sciences, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi, India India (e-mail: [email protected]). J Card Crit Care 2020;3:89–96 Abstract Bacterial infections are common causes of sepsis in the intensive care units. However, usually a finite number of Gram-negative bacteria cause sepsis (mostly according to the hospital flora). Some organisms such as Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus are relatively common. Others such as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Chryseobacterium indologenes, Shewanella putrefaciens, Ralstonia pickettii, Providencia, Morganella species, Nocardia, Elizabethkingia, Proteus, and Burkholderia are rare but of immense importance to public health, in view of the high mortality rates these are associated with. Being aware of these organisms, as the cause of hospital-acquired infections, helps in the prevention, Keywords treatment, and control of sepsis in the high-risk cardiac surgical patients including in ► uncommon pathogens heart transplants. Therefore, a basic understanding of when to suspect these organ- ► hospital-acquired isms is important for clinical diagnosis and initiating therapeutic options. This review infection discusses some rarely appearing pathogens in our intensive care unit with respect to ► cardiac surgical the spectrum of infections, and various antibiotics that were effective in managing intensive care unit these bacteria. -

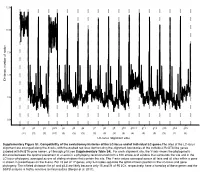

LC-Locus Alignment Sites Distance, Number of Nodes Supplementary

12.5 10.0 7.5 5.0 Distance, number of nodes 2.5 0.0 g1 g2 g3 g3.5 g4 g5 g6 g7 g8 g9 g10 g10.1 g11 g12 g13 g14 g15 (11) (3) (3) (10) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (3) (4) (3) (3) (3) (2) (3) LC-locus alignment sites Supplementary Figure S1. Compatibility of the evolutionary histories of the LC-locus and of individual LC genes.The sites of the LC-locus alignment are arranged along the X-axis, with the dashed red lines demarcating the alignment boundaries of the individual RcGTA-like genes (labeled with RcGTA gene names, g1 through g15; see Supplementary Table S4). For each alignment site, the Y-axis shows the phylogenetic distance between the optimal placement of a taxon in a phylogeny reconstructed from a 100 amino-acid window that surrounds the site and in the LC-locus phylogeny, averaged across all sliding windows that contain the site. The Y-axis values averaged across all taxa and all sites within a gene is shown in parentheses on the X-axis. For 15 out of 17 genes, only 2-4 nodes separate the optimal taxon position in the LC-locus and gene phylogeny. The inflated distances for g1 and g3.5 are likely because only 15 and 21 of 95 LCs, respectively, have a homolog of these genes and the SSPB analysis is highly sensitive to missing data (Berger et al. 2011). a. Bacteria Unassigned Thermotogae Tenericutes Synergistetes Spirochaetes Proteobacteria ylum Planctomycetes h p Firmicutes Deferribacteres Cyanobacteria Chloroflexi Bacteroidetes Actinobacteria Acidobacteria 1(11,750) 2(1,750) 3(2,538) 4(168) 5(51) 6(54) 7(43) 8(32) 9(26) 10(40) 11(33) 12(198) 13(173) 14(101) 15(98) 16(43) 17(114) Number of rcc01682−rcc01698 homologs in a cluster b. -

Rickettsialpox-A Newly Recognized Rickettsial Disease V

Public Health Reports Vol. 62 * MAY 30, 1947 * No. 22 Printed With the Approval of the Bureau of the Budget as Required by Rule 42 of the Joint-Committee on Printing RICKETTSIALPOX-A NEWLY RECOGNIZED RICKETTSIAL DISEASE V. RECOVERY OF RICKETTSIA AKARI FROM A HOUSE MOUSE (MUS MUSCULUS)1 By ROBERT J. HUEBNER, Senior Assistant Surgeon, WILLIAm L. JELLISON, Parasitologist, CHARLES ARMSTRONG, Medical Director, United States Public Health Service Ricketttia akari, the causative agent of rickettsialpox, was isolated from the blood of persons ill with this disease (1) and from rodent mites Allodermanyssus sanguineus Hirst inhabiting the domicile of ill per- sons (2). This paper describes the isolation of R. akari from a house mouse (Mus musculus) trapped on the same premises-a housing development in the citr of New York where more than 100 cases of rickettsialpox have occurred (3), (4), (5), (6). Approximately 60 house mice were trapped in the basements of this housing development where rodent harborage existed in store rooms and in incinerator ashpits. Engorged mites were occasionally found attached to the mice, the usual site of attachment being the rump. Mites were frequently found inside the box traps after the captured mice were removed. Early attempts to isolate the etiological agent of rickettisalpox from these mice were complicated by the presence of choriomeningitis among them. Twelve successive suspensions of mouse tissue, repre- senting 16 house mice, inoculated intracerebrally into laboratory mice (Swiss strain) and intraperitoneally into guinea pigs resulted in the production of a highly lethal disease in both species which was identified immunologically as choriomeningitis.