ECFG Libya 2021R.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

Nutrition, Lifestyle and Diabetes-Risk of School Children in Derna

www.doktorverlag.de [email protected] Tel: 0641-5599888Fax:-5599890 Tel: D-35396 GIESSEN STAUFENBERGRING 15 STAUFENBERGRING VVB LAUFERSWEILERVERLAG VVB LAUFERSWEILER VERLAG VVB LAUFERSWEILER édition scientifique 9 783835 955103 ISBN 3-8359-5510-1 ISBN © KaYann -Fotolia.com © KaYann © JoseManuelGelpi-Fotolia.com VVB TAWFEG ELHISADI NUTRITION, LIFESTYLE AND DIABETES-RISK OF CHILDREN IN DERNA, LIBYA NUTRITION, LIFESTYLEANDDIABETES-RISKOF SCHOOL CHILDRENINDERNA,LIBYA TAWFEG A.ELHISADI Agrarwissenschaften, Ökotrophologie der Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen INAUGURAL-DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades VVB LAUFERSWEILER VERLAG VVB LAUFERSWEILER und Umweltmanagement im Fachbereich édition scientifique . Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne schriftliche Zustimmung des Autors oder des Verlages unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. 1. Auflage 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Author or the Publishers. 1st Edition 2009 © 2009 by VVB LAUFERSWEILER VERLAG, Giessen Printed in Germany VVB LAUFERSWEILERédition scientifique VERLAG STAUFENBERGRING 15, D-35396 GIESSEN Tel: 0641-5599888 Fax: 0641-5599890 email: [email protected] www.doktorverlag.de Institut für Ernährungswissenschaft Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen Nutrition, Lifestyle and Diabetes-risk of School Children in Derna, Libya INAUGURAL-DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades im Fachbereich Agrarwissenschaften, Ökotrophologie und Umweltmanagement der Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen eingereicht von Tawfeg A. A. Elhisadi aus Libyen Giessen 2009 Dekanin: Prof. Dr. I. U. Leonhäuser Prüfungsvorsitzende: Prof. Dr. A. Evers 1. -

Vol 39 No 48 November 26

Notice of Forfeiture - Domestic Kansas Register 1 State of Kansas 2AMD, LLC, Leawood, KS 2H Properties, LLC, Winfield, KS Secretary of State 2jake’s Jaylin & Jojo, L.L.C., Kansas City, KS 2JCO, LLC, Wichita, KS Notice of Forfeiture 2JFK, LLC, Wichita, KS 2JK, LLC, Overland Park, KS In accordance with Kansas statutes, the following busi- 2M, LLC, Dodge City, KS ness entities organized under the laws of Kansas and the 2nd Chance Lawn and Landscape, LLC, Wichita, KS foreign business entities authorized to do business in 2nd to None, LLC, Wichita, KS 2nd 2 None, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas were forfeited during the month of October 2020 2shutterbugs, LLC, Frontenac, KS for failure to timely file an annual report and pay the an- 2U Farms, L.L.C., Oberlin, KS nual report fee. 2u4less, LLC, Frontenac, KS Please Note: The following list represents business en- 20 Angel 15, LLC, Westmoreland, KS tities forfeited in October. Any business entity listed may 2000 S 10th St, LLC, Leawood, KS 2007 Golden Tigers, LLC, Wichita, KS have filed for reinstatement and be considered in good 21/127, L.C., Wichita, KS standing. To check the status of a business entity go to the 21st Street Metal Recycling, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station at 210 Lecato Ventures, LLC, Mullica Hill, NJ https://www.kansas.gov/bess/flow/main?execution=e2s4 2111 Property, L.L.C., Lawrence, KS 21650 S Main, LLC, Colorado Springs, CO (select Business Entity Database) or contact the Business 217 Media, LLC, Hays, KS Services Division at 785-296-4564. -

The 2011 Libyan Revolution and Gene Sharp's Strategy of Nonviolent Action

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2012 The 2011 Libyan revolution and Gene Sharp's strategy of nonviolent action : what factors precluded nonviolent action in the 2011 Libyan uprising, and how do these reflect on Gene Sharp's theory? Siobhan Lynch Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Political History Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Lynch, S. (2012). The 2011 Libyan revolution and Gene Sharp's strategy of nonviolent action : what factors precluded nonviolent action in the 2011 Libyan uprising, and how do these reflect on Gene Sharp's theory?. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/74 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/74 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Use of Thesis This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. -

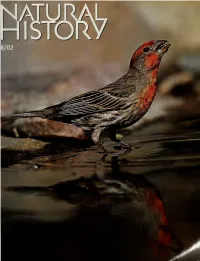

AMNH Digital Library

^^<e?& THERE ARE THOSE WHO DO. AND THOSE WHO WOULDACOULDASHOULDA. Which one are you? If you're the kind of person who's willing to put it all on the line to pursue your goal, there's AIG. The organization with more ways to manage risk and more financial solutions than anyone else. Everything from business insurance for growing companies to travel-accident coverage to retirement savings plans. All to help you act boldly in business and in life. So the next time you're facing an uphill challenge, contact AIG. THE GREATEST RISK IS NOT TAKING ONE: AIG INSURANCE, FINANCIAL SERVICES AND THE FREEDOM TO DARE. Insurance and services provided by members of American International Group, Inc.. 70 Pine Street, Dept. A, New York, NY 10270. vww.aig.com TODAY TOMORROW TOYOTA Each year Toyota builds more than one million vehicles in North America. This means that we use a lot of resources — steel, aluminum, and plastics, for instance. But at Toyota, large scale manufacturing doesn't mean large scale waste. In 1992 we introduced our Global Earth Charter to promote environmental responsibility throughout our operations. And in North America it is already reaping significant benefits. We recycle 376 million pounds of steel annually, and aggressive recycling programs keep 18 million pounds of other scrap materials from landfills. Of course, no one ever said that looking after the Earth's resources is easy. But as we continue to strive for greener ways to do business, there's one thing we're definitely not wasting. And that's time. www.toyota.com/tomorrow ©2001 JUNE 2002 VOLUME 111 NUMBER 5 FEATURES AVIAN QUICK-CHANGE ARTISTS How do house finches thrive in so many environments? By reshaping themselves. -

Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Wolfram Lacher Fault Lines of the Revolution Political Actors, Camps and Conflicts in the New Libya RP 4 May 2013 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2013 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the author(s). SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 3−4 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (English version of SWP-Studie 5/2013) The English translation of this study has been realised in the context of the project “Elite change and new social mobilization in the Arab world”. The project is funded by the German Foreign Office in the framework of the transformation partnerships with the Arab World and the Robert Bosch Stiftung. It cooperates with the PhD grant programme of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and the Hanns-Seidel-Stiftung. Table of Contents 5 Problems and Conclusions 7 Parameters of the Transition 9 Political Forces in the New Libya 9 Camps and Interests in Congress and Government 10 Ideological Camps and Tactical Alliances 12 Fault Lines of the Revolution 14 The Zeidan Government 14 Parliamentary and Extra-Parliamentary Islamists 14 The Grand Mufti’s Network and Influence 16 The Influence of Islamist Currents -

After Gaddafi 01 0 0.Pdf

Benghazi in an individual capacity and the group it- ures such as Zahi Mogherbi and Amal al-Obeidi. They self does not seem to be reforming. Al-Qaeda in the found an echo in the administrative elites, which, al- Islamic Maghreb has also been cited as a potential though they may have served the regime for years, spoiler in Libya. In fact, an early attempt to infiltrate did not necessarily accept its values or projects. Both the country was foiled and since then the group has groups represent an essential resource for the future, been taking arms and weapons out of Libya instead. and will certainly take part in a future government. It is unlikely to play any role at all. Scenarios for the future The position of the Union of Free Officers is unknown and, although they may form a pressure group, their membership is elderly and many of them – such as the Three scenarios have been proposed for Libya in the rijal al-khima (‘the men of the tent’ – Colonel Gaddafi’s future: (1) the Gaddafi regime is restored to power; closest confidants) – too compromised by their as- (2) Libya becomes a failing state; and (3) some kind sociation with the Gaddafi regime. The exiled groups of pluralistic government emerges in a reunified state. will undoubtedly seek roles in any new regime but The possibility that Libya remains, as at present, a they suffer from the fact that they have been abroad divided state between East and West has been ex- for up to thirty years or more. -

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

Big Sandbox,” However It May Be Interpreted, Brought with It Extraordinary Enchantment

eScholarship California Italian Studies Title The Embarrassment of Libya. History, Memory, and Politics in Contemporary Italy Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9z63v86n Journal California Italian Studies, 1(1) Author Labanca, Nicola Publication Date 2010 DOI 10.5070/C311008847 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Embarrassment of Libya: History, Memory, and Politics in Contemporary Italy Nicola Labanca The past weighs on the present. This same past can, however, also constitute an opportunity for the future. If adequately acknowledged, the past can inspire positive action. This seems to be the maxim that we can draw from the history of Italy in the Mediterranean and, in particular, the history of Italy's relationship with Libya. Even the most recent “friendship and cooperation agreement” between Italy and Libya, signed August 30, 2008 by Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi and Libyan leader Colonel Moammar Gadhafi, affirms this. Italy’s colonial past in Libya has been a source of political tensions between the two nations for the past forty years. Now, the question emerges: will the acknowledgement of this past finally help to reconcile the two countries? The history of Italy’s presence in Libya (1912-1942) is rather different from the more general history of the European colonial expansion. The Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (referred to by the single name “Libya” in the literary and rhetorical culture of liberal Italy) were among the few African territories that remained outside of the European dominion, together with Ethiopia (which defeated Italy at Adwa in 1896) and rubber-rich Liberia. -

Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2256 Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War by Andrew Engel May 20, 2014 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Andrew Engel Andrew Engel, a former research assistant at The Washington Institute, recently received his master's degree in security studies at Georgetown University and currently works as an Africa analyst. Brief Analysis Long-simmering tensions between non-Islamist and Islamist forces have boiled over into military actions centered around Benghazi and Tripoli, entrenching the country's rival alliances and bringing them ever closer to civil war. n May 16, former Libyan army general Khalifa Haftar launched "Operation Dignity of Libya" in Benghazi, O aiming to "c leanse the city of terrorists." The move came three months after he announced the overthrow of the government but failed to act on his proclamation. Since Friday, however, army units loyal to Haftar have actively defied armed forces chief of staff Maj. Gen. Salem al-Obeidi, who called the operation "a coup." And on Monday, sympathetic forces based in Zintan extended the operation to Tripoli. These and other developments are edging the country closer to civil war, complicating U.S. efforts to stabilize post-Qadhafi Libya. DIVIDING LINES I slamists and non-Islamist forces have long been contesting each other's claims to being the legitimate heart of the 2011 revolution. Islamist factions such as the Muslim Brotherhood-related Justice and Construction Party and the Loyalty to the Martyrs Bloc have dominated the General National Congress (GNC) since summer 2013, when the forcibly passed Political Isolation Law effectively barred all former Qadhafi regime members -- even those who had fought the regime -- from participating in government for ten years. -

Brookings Doha Center - Stanford University Project on Arab Transitions

CENTER ON DEMOCRACY, DEVELOPMENT & THE RULE OF LAW STANFORD UNIVERSITY BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER - STANFORD UNIVERSITY PROJECT ON ARAB TRANSITIONS PAPER SERIES Number 4, March 2014 PERSONNEL CHANGE OR PERSONAL CHANGE? RETHINKING LIBYA’S POLITICAL ISOLATION LAW ROMAN DAVID AND HOUDA MZIOUDET PROGRAM ON ARAB REFORM AND DEMOCRACY, CDDRL B ROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high- quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its scholars. Copyright © 2014 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha T A B LE OF C ON T EN T S I. Executive Summary ...........................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 III. The Political Isolation Law and its Alternatives ...............................................................4 IV. Assessing the PIL and its Reconciliatory Alternatives ....................................................7 Establishment of a Trustworthy Government ..........................................................,..7 -

The Mediterranean Diet 228�

DIET� Newly Revised and Updated Marissa Cloutier, MS, RD and Eve Adamson Recipes by Eve Adamson Produced by Amaranth This book is dedicated to Michael and Sophie. Wishing you both good health and a long, happy life. —M. C. To my children, Angus and Emmett, that they may learn to eat well, live well, and take their health into their own hands. —E. A. ojPCmlpM� Contents Introduction 1� Part I: The Benefits of Eating Mediterranean 13� 1: Mediterranean Magic 15� 2: A Recipe for Wellness 39� 3: Olive Oil and Other Fats:� What You Need to Know 67� 4: Vegetables: The Heart and Soul of the � Traditional Mediterranean Diet 93� 5: The Fruits of Good Health 122� 6: The Grains, Legumes, Nuts, and Seeds � of the Mediterranean 147� 7: Meat, Poultry, Fish, Dairy, and Egg � Consumption the Mediterranean Way 171� 8: Embracing the Mediterranean Lifestyle 205� Contents� 9: Losing Weight and Living Well � on the Mediterranean Diet 228� Part II: Recipes for Enjoying the Mediterranean Diet 247� Mediterranean Snack Food: An Art Form, a Meal 249� • Tapas (Appetizers) 251� • Salads 270� • Soups and Stews 278� • The Main Course 286� • Desserts 306� Resources 317� Searchable Terms 323� Acknowledgments About the Author Cover Copyright About the Publisher ojPCmlpM� Introduction� If you grew up with a television set, you’ve probably seen the familiar scenario: a family gathered around the breakfast table, their plates piled high with eggs, bacon, sausage, maybe even a breakfast steak and a formidable stack of pancakes made with that ubiquitous box of handy biscuit mix. A bottle of maple-flavored syrup and a stick of butter (or tub of margarine) adorned the center of the table.