The Turkmen Identity Crisis in the Fifteenth-Century Middle East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forum of Ethnogeopolitics

Forum of EthnoGeoPolitics ! Figure 1: French Map of Iran or Persia in 1749 (drafted by Robert de Vaugoudy) in which Azerbaijan is shown below the Araxes River (Source: Pictures of the Planet). A Case of Historical Misconceptions?—Congressman Rohrabacher’s Letter to Hillary Clinton Regarding Azerbaijan Kaveh Farrokh Abstract United States Congressman Dana Rohrabacher—a former member of the Reagan Administration, who has represented several Californian congressional districts from 1989 till the present-day—dispatched a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on July 26, 2012 outlining support for the separation of Iranian Azerbaijan and the joining of this entity to the Republic of Azerbaijan. The letter promotes the notion of the historical existence of a Greater Azerbaijani kingdom that was divided by Iran and Russia during the early 19th century. This paper examines the treaties of Gulistan (1813) and Turkmenchai (1828) between Iran and Russia, historical sources and maps and other academic works to examine the validity of the “Greater Forum of EthnoGeoPolitics Vol.1 No.1 Spring 2013 9 Forum of EthnoGeoPolitics Azerbaijan” thesis. Examination of these sources, however, does not provide evidence for the existence of a “Greater Azerbaijan” in history. Instead these sources reveal the existence of ‘Azerbaijan’ as being a region and province within the Iranian realm since antiquity, located below (or south of ) the Araxes River; in contrast, the modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan is located north (or above) the Araxes River. It never existed under the title “Azerbaijan” until the arrival of the Musavats (1918) and then the Soviets (1920). -

The Relationship Between Mozafaria Complex and the Spatial Organization of Tabriz City from the Qara Qoyunlu to the Qajar Period

Bagh- e Nazar, 15 (68): 15-26 /Feb. 2019 DOI: 10.22034/bagh.2019.81651 Persian translation of this paper entitled: ارتباط مجموعۀ مظفریه با سازمان فضایی شهر تبریز از دورۀ قراقویونلوها تا دورۀ قاجار is also published in this issue of journal. The Relationship between Mozafaria Complex and the Spatial Organization of Tabriz City from the Qara Qoyunlu to the Qajar Period Shabnam Mohammadzadeh*1, Seyed Amir Mansouri2 1. Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran 2. Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran Received 2018/03/02 revised 2018/08/23 accepted 2018/08/30 available online 2019/01/21 Abstract Urban spatial organization is a subjective issue, reflecting the order resulted from the relationship between the city’s elements. Understanding the position and role of a city element in the city as a whole requires discovering its relationship with the spatial organization. In other words, the city’s order is like a system and a whole. Based on the theory of city’s spatial organization, the current study is an attempt to investigate the relationship between Mozafaria Complex and the city’s spatial organization indicators in Tabriz City. In other words, this study examined the role of this complex in the whole system of the city from the time of the Qara Qoyunlu to the Qajar. In this study, the systemic role of Mozafaria Complex is not limited to its function and its features. The impetus behind this study is to discover the features defined in relation to other elements of the city. The method of the study is descriptive-analytical and deductive-exploratory; the library-research method was also used for data collection. -

Download This PDF File

ISSN 1712-8056[Print] Canadian Social Science ISSN 1923-6697[Online] Vol. 8, No. 2, 2012, pp. 132-139 www.cscanada.net DOI:10.3968/j.css.1923669720120802.1985 www.cscanada.org Iranian People and the Origin of the Turkish-speaking Population of the North- western of Iran LE PEUPLE IRANIEN ET L’ORIGINE DE LA POPULATION TURCOPHONE AU NORD- OUEST DE L’IRAN Vahid Rashidvash1,* 1 Department of Iranian Studies, Yerevan State University, Yerevan, exception, car il peut être appelé une communauté multi- Armenia. national ou multi-raciale. Le nom de Azerbaïdjan a été *Corresponding author. l’un des plus grands noms géographiques de l’Iran depuis Received 11 December 2011; accepted 5 April 2012. 2000 ans. Azar est le même que “Ashur”, qui signifi e feu. En Pahlavi inscriptions, Azerbaïdjan a été mentionnée Abstract comme «Oturpatekan’, alors qu’il a été mentionné The world is a place containing various racial and lingual Azarbayegan et Azarpadegan dans les écrits persans. Dans groups. So that as far as this issue is concerned there cet article, la tentative est faite pour étudier la course et is no difference between developed and developing les gens qui y vivent dans la perspective de l’anthropologie countries. Iran is not an exception, because it can be et l’ethnologie. En fait, il est basé sur cette question called a multi-national or multi-racial community. que si oui ou non, les gens ont résidé dans Atropatgan The name of Azarbaijan has been one of the most une race aryenne comme les autres Iraniens? Selon les renowned geographical names of Iran since 2000 years critères anthropologiques et ethniques de personnes dans ago. -

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Jnasci-2015-1195-1202

Journal of Novel Applied Sciences Available online at www.jnasci.org ©2015 JNAS Journal-2015-4-11/1195-1202 ISSN 2322-5149 ©2015 JNAS Relationships between Timurid Empire and Qara Qoyunlu & Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens Jamshid Norouzi1 and Wirya Azizi2* 1- Assistant Professor of History Department of Payame Noor University 2- M.A of Iran’s Islamic Era History of Payame Noor University Corresponding author: Wirya Azizi ABSTRACT: Following Abu Saeed Ilkhan’s death (from Mongol Empire), for half a century, Iranian lands were reigned by local rules. Finally, lately in the 8th century, Amir Timur thrived from Transoxiana in northeastern Iran, and gradually made obedient Iran and surrounding countries. However, in the Northwest of Iran, Turkmen tribes reigned but during the Timurid raids they had returned to obedience, and just as withdrawal of the Timurid troops, they were quickly back their former power. These clans and tribes sometimes were troublesome to the Ottoman Empires and Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Due to the remoteness of these regions of Timurid Capital and, more importantly, lack of permanent government administrations and organizations of the Timurid capital, following Amir Timur’s death, because of dynastic struggles among his Sons and Grandsons, the Turkmens under these conditions were increasing their power and then they had challenged the Timurid princes. The most important goals of this study has focused on investigation of their relationships and struggles. How and why Timurid Empire has begun to combat against Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens; what were the reasons for the failure of the Timurid deal with them, these are the questions that we try to find the answers in our study. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

![Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3444/fall-of-constantinople-pmunc-2018-contents-1093444.webp)

Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents

[FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 CONTENTS Letter from the Chair and CD………....…………………………………………....[3] Committee Description…………………………………………………………….[4] The Siege of Constantinople: Introduction………………………………………………………….……. [5] Sailing to Byzantium: A Brief History……...………....……………………...[6] Current Status………………………………………………………………[9] Keywords………………………………………………………………….[12] Questions for Consideration……………………………………………….[14] Character List…………………...………………………………………….[15] Citations……..…………………...………………………………………...[23] 2 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Dear delegates, Welcome to PMUNC! My name is Atakan Baltaci, and I’m super excited to conquer a city! I will be your chair for the Fall of Constantinople Committee at PMUNC 2018. We have gathered the mightiest commanders, the most cunning statesmen and the most renowned scholars the Ottoman Empire has ever seen to achieve the toughest of goals: conquering Constantinople. This Sultan is clever and more than eager, but he is also young and wants your advice. Let’s see what comes of this! Sincerely, Atakan Baltaci Dear delegates, Hello and welcome to PMUNC! I am Kris Hristov and I will be your crisis director for the siege of Constantinople. I am pleased to say this will not be your typical committee as we will focus more on enacting more small directives, building up to the siege of Constantinople, which will require military mobilization, finding the funds for an invasion and the political will on the part of all delegates.. Sincerely, Kris Hristov 3 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 COMMITTEE DESCRIPTION The year is 1451, and a 19 year old has re-ascended to the throne of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed II is now assembling his Imperial Court for the grandest city of all: Constantinople! The Fall of Constantinople (affectionately called the Conquest of Istanbul by the Turks) was the capture of the Byzantine Empire's capital by the Ottoman Empire. -

DISTINGUISHED WOMEN in HISTORY of AZERBAIJANI ATABAY, AQ QOYUNLU and SAFAVID STATES Conclusion

42, WINTER 2019 Nargiz F. AKHUNDOVA PhD in History DISTINGUISHED WOMEN IN HISTORY OF AZERBAIJANI ATABAY, AQ QOYUNLU AND SAFAVID STATES Conclusion. See the beginning in IRS-Heritage, № 41, 2019 www.irs-az.com 5 From the past his list of outstanding women’s names could be mon knowledge that the Azerbaijani Ildeniz rulers, in continued. However, the personality of Momine fact, were subsequently at the helm of state. It is note- TKhatun, the wife of Azerbaijani atabay (ruler) worthy that Z. M. Buniyadov made a substantial contri- Ildeniz and mother of prominent Ildenizid rulers Jahan bution to the studies regarding the nearly century-long Pahlavan (1175-1186) and Qizil Arslan, is particularly re- historical period of the Atabay state’s existence. The markable. The concept of women’s governing role in Orientalist conducted extensive research of the avail- the state system in the Atabay state should be generally able sources. The Arabic language sources he studied emphasized as well. included Ibn al-Asir’s (1160-1233) (“al-Kamil fi-t-ta rikh” This personality existed during an earlier era that was or ”Perfect on history”), Sibt al-Jawzi’s (1185-1256) “Mir by far no less tension-filled than that of the previously at az-zaman fi-tarikh al-ayan” (“The mirror of time in the mentioned Sara Khatun and Tajlu Begim, i.e. the epoch chronicle of celebrities”), Sadr ad-Din Ali al-Husayni’s of the Ildenizid state (1136-1225). This time period is of- “Zubdat at-tavarikh fi akhbar al-umara va-l-mulyuk as- ten referred to by historiographers as the Renaissance Seljuqiyya” (“The cream of the crop in the chronicles epoch, which saw the emergence of great poets, po- that contain data about Seljuq Emirs and rulers”), etc. -

Äs T Studies Association «Bulletin^ 12 No. 2 (May 1978)

.** äs t Studies Association «Bulletin^ 12 no. 2 (May 1978), ISLAMIC NUMISMATICS Sections l and 2 by Michael L. Bates The American Numismatic Society Every Student of pre-raodern Islamic political, social, economic, or cultural history is aware in a general way of the importance of nuraisraatic evidence, but it has to be admitted thst for the roost part this awareness is evidenced raore in lip ser-vice than in practice. Too many historians consider numismatics an arcane and complex study best left to specialists. All too often, histori- ans, if they take coin evidence into account at all, suspend their normal critical judgement to accept without cjuestion the readings and interpretations of the numismatist. Or. the other hand, numismatists, in the past especially but to a large extent still today, are often amateurs, self-taught through practice with little or no formal.historical and linguistic training. This is true even öf museum Professionals in Charge of Islamic collections, ho matter what their previous training: The need tc deal with the coinage of fourteen centuries, from Morocco to the Fr.ilippines, means that the curator spends most of his time workir.g in areas in which he is, by scholarly Standards, a layman. The best qual- ified Student of any coin series is the specialist with an ex- pert knowledge of the historical context from which the coinage coraes. Ideally, any serious research on a particular region and era should rest upon äs intensive a study of the nvunismatic evi- dence äs of the literary sources. In practice, of course, it is not so easy, but it is easier than many scholars believe, and cer- tainly much «asier than for a numismatist to become =. -

Universi^ Micn^Lms

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting througli an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

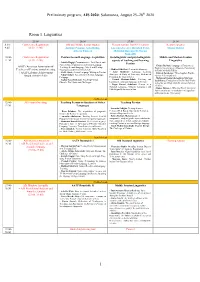

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala