Revisiting Albert Camus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

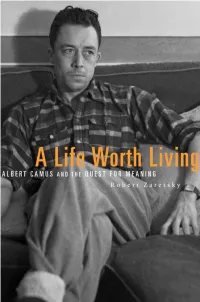

A Life Worth Living

A LIFE WORTH LIVING A LIFE WORTH LIVING Albert Camus and the Quest for Meaning robert zaretsky the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, En gland 2013 Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College all rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Zaretsky, Robert, 1955– A life worth living : Albert Camus and the quest for meaning / Robert Zaretsky. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 72476- 1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Camus, Albert, 1913– 1960. 2. Conduct of life. I. Title. B2430.C354Z37 2013 194—dc23 2013010473 CONTENTS Prologue 1 1. Absurdity 11 2. Silence 59 3. Mea sure 92 4. Fidelity 117 5. Revolt 148 Epilogue 185 Notes 199 A c k n o w l e d g m e n t s 2 2 1 Index 223 A LIFE WORTH LIVING PROLOGUE “Even my death will be contested. And yet what I desire most today is a quiet death, which would bring peace to those whom I love.”1 Albert Camus’ prediction, written in the last decade of his life, has been borne out, though perhaps not his hope. Over the past several years, contests have simmered and burst over the French Algerian writer’s legacy. Shortly after becoming France’s president, Nicolas Sarkozy made a state visit to Algeria. The visit garnered more than the usual attention, in part because Sarkozy had come to offi ce with a reputation as a bluntly spoken conservative who saw no reason for France to apologize for its role as a colonial power. -

Number 30 a Stranger Again

hamIsh hamIlToN preseNTs Five Dials Number 30 A Stranger Again The Camus Issue — CurTIs GIllespIe The Complicated Legacy Deborah levy The Death Drive alberT Camus Summer in Algiers . Plus: rotated, distorted, warped street art & Camus’s handwriting. CONTRIBUTORS alberT Camus was born in Mondovi, Algeria, in 1913. An avid sportsman, Camus claimed to have learned all he knew about morality and the obligations of men from football. He preferred to write whilst standing up and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. While on a trip to the United States, Camus visited the New York Zoo twenty times. He was also the owner of a cat called Cigarette. CurTIs GIllespIe is the author of five books, including the memoirsAlmost There and Playing Through, and the novel Crown Shyness. Gillespie has won three National Magazine Awards in Canada for his writing on politics, science and the arts. In 2010 he co-founded the award-winning narrative journalism magazine Eighteen Bridges, which he also edits. Like Camus, he was a football goalkeeper. He played for the University of Alberta in the early eighties. Deborah levy is the author of many works, including, Billy & Girl, The Unloved and Swallowing Geography. In 2012 her novel Swimming Home was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Having trained at Darlington College of Arts, she left to become a playwright, creating work for the Royal Shakespeare Company among others. Levy was a Fellow in Creative Arts at Trinity College, Cambridge. Her most recent essay, Things I Don’t Want to Know is a response to George Orwell’s Why I Write and her next novel, Hot Milk,will be published by Hamish Hamilton in 2015. -

Albert Camus' Biography

Albert Camus’ biography (briefly) Born November 7th, 1913, in Mondovi, a small village in French Algeria where Camus’ great grandfather, originally from Bordeaux in France, had settled in the early 19th century. Camus’ father was a shipping wine clerk and military veteran who died in WW1 when Camus was less than a year old. All he knew of his father was that he had become violently ill after witnessing a public execution. Camus’ mother was illiterate, partially deaf, and poor. After her husband’s death, Camus, his mother and his older brother lived with his maternal uncle and grandmother in a cramped three-room apartment in a working-class area of Algiers where his mother worked in an ammunition factory and cleaned houses. Camus was able to afford elementary school because of his dead father’s veteran status and, although he had recurring health issues, including tuberculosis, he distinguished himself as a student and won a scholarship to the Grand Lycee. There he was an avid reader (Gide, Proust, Verlaine, etc.). In 1932, Camus received his Baccalauréat Degree; in 1933, he enrolled at the University of Algeria for an advanced degree. 1933-1937: Married Simone Hié, divorced her, briefly joined the Communist Party, became disillusioned with it, and was expelled. During this period, he began his theatrical and writing career. 1940s—Married Francine Faure, worked as a journalist in France for the French Resistance newspaper Combat, wrote The Stranger which brought him immediate literary renown, followed by the philosophic The Myth of Sisyphus and became an editor at Gallimard Publishing. -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

A Critique of Humoristic Absurdism

A Critique of Humoristic Absurdism A Critique of Humoristic Absurdism Problematizing the legitimacy of a humoristic disposition toward the Absurd A Critique of Humoristic Absurdism Copyright © 2020 Thom Hamer Thom Hamer All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any way or by any means without the prior permission of the author or, when applicable, of the publishers of the scientific papers. Image on previous page: Yue Minjun (2003), Garbage Hill Student number: 3982815 Graphic design: Mirelle van Tulder Date: February 5th 2020 Printed by Ipskamp Printing Word count: 32,397 Institution: Utrecht University Contents Study: Research Master Philosophy Summary 9 Document: Final Thesis Foreword 10 Supervisor: prof. dr. Paul Ziche Introduction 12 Second Reader: dr. Hans van Stralen 1. The Philosophy of Humor 21 Third Reader: prof. dr. Mauro Bonazzi 1.1. A history of negligence and rejection 24 1.2. Important distinctions 33 1.3. Theories of humor 34 1.4. Defense of the Incongruity Theory 41 1.5. Relevance of relief and devaluation 52 1.6. Operational definition 54 2. The Notion of the Absurd 59 2.1. Camusian notion: meaninglessness 61 2.2. Tolstoyan notion: mortality 63 2.3. Nagelian notion: trivial commitments 67 2.4. Modified notion: dissolution of resolution 71 2.5. Justificatory guideline for a disposition toward the Absurd 78 3. Humoristic Absurdism 83 3.1. What is Humoristic Absurdism? 85 3.2. Cultural expressions of Humoristic Absurdism 87 3.3. Defense of Humoristic Absurdism 92 4. Objections against the humoristic disposition toward the Absurd 101 4.1. -

Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: from Undecidability to Übercommunication

Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: From Undecidability to Übercommunication by Jorge Lizarzaburu B.A., USFQ, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication 2012 This thesis entitled: Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: From Undecidability to Übercommunication written by Jorge M. Lizarzaburu has been approved for the Department of Communication Gerard Hauser Janice Peck Robert Craig Date 5/31/2012 The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline iii Lizarzaburu, Jorge M. (M.A., Communication, Department of Communication) Albert Camus and Absurd Communication: From Undecidability to Übercommunication Thesis directed by professor Gerard Hauser Communication conceived as understanding is a normative telos among scholars in the field. Absurdity, in the work of Albert Camus, can provide us with a framework to go beyond communication understood as a binary (understanding and misunderstanding) and propose a new conception of communication as absurd. That is, it is an impossible task, however necessary thus we need to embrace its absurdity and value the effort itself as much as the result. Before getting into Camus’ arguments I explain the work of Friedrich Nietzsche to understand the French philosopher in more detail. I describe eternal recurrence and Übermensch as two concepts that can be related to communication as absurd. Then I explain Camus’ notion of absurdity using a Nietzschean lens. -

Albert Camus' Dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky Sean Derek Illing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Between nihilism and transcendence : Albert Camus' dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky Sean Derek Illing Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Illing, Sean Derek, "Between nihilism and transcendence : Albert Camus' dialogue with Nietzsche and Dostoevsky" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1393. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1393 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. BETWEEN NIHILISM AND TRANSCENDENCE: ALBERT CAMUS’ DIALOGUE WITH NIETZSCHE AND DOSTOEVSKY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Sean D. Illing B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 M.A., University of West Florida, 2009 May 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the product of many supportive individuals. I am especially grateful for Dr. Cecil Eubank’s guidance. As a teacher, one can do no better than Professor Eubanks. Although his Socratic glare can be terrifying, there is always love and wisdom in his instruction. It is no exaggeration to say that this work would not exist without his support. At every step, he helped me along as I struggled to articulate my thoughts. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Amnesty International (2015) Death Sentences and Executions 2014, https://www.amnesty.org.uk/sites/ default/files/death_sentences_and_executions_2014 _ en.pdf, accessed 12 March 2015. Appiah, K. A. (2007) Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (New York: W. W. Norton). Archambault, P. (1972) Camus’ Hellenic Sources (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press). Arendt, H. (1994) Essays in Understandingg (New: York: Schocken Books). Aristotle (1932) Politics, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press). Aristotle (1976) The Nicomachean Ethics, trans. J. A. K Thomson (London and New York: Penguin Books). Aristotle (2013) Poetics, trans. A. Kenny (Oxford: Oxford University Press). Barthes, R. (1972) Critical Essays (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press). Beck, U. and Sznaider, N. (2006) ‘Unpacking Cosmopolitanism for the Social Sciences: A Research Agenda’, British Journal of Sociology, 57(1), 1–23. Benjamin, W. (1999) ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ in Illuminations (London: Pimlico). Brown, G. W. (2009) Grounding Cosmopolitanism: From Kant to the Idea of a Cosmopolitan Constitution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press). Brown, G. W. and Held, D. (eds) (2010) The Cosmopolitanism Readerr (Cambridge: Polity). DOI: 10.1057/9781137525833.0010 Bibliography Camus, A. (1946–7) ‘The Human Crisis’, Twice a Year, 14–15, 19–33. Camus, A. (1948) The Plague (New York: Vintage Books). Camus, A. (1950) Actuelles I: Chroniques, 1944–1948 (Paris: Gallimard). Camus, A. (1956) The Rebell (New York: Vintage Books). Camus, A. (1957) ‘Nobel Banquet Speech’, 10 December, http://www. nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1957/camus-speech. html, accessed 14 November 2014. Camus, A. (1960) Resistance, Rebellion and Death (New York: Vintage Books). -

Scott Baugh on the First

Albert Camus. The First Man. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995. viii + 325 pp. $23.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-679-43937-0. Reviewed by Scott L. Baugh Published on H-PCAACA (April, 1996) Although controversy surrounded his life and family--primarily his widow--decided not to pub‐ work, Albert Camus remains one of the most sig‐ lish the unfinished manuscript. nificant and influential literary, political, and Camus' last work remained unpublished for philosophical minds of the 20th century. The First 34 years, until 1994; in 1995, Knopf released Man, Camus' unfinished autobiographical novel, David Hapsgood's translation of The First Man in offers readers a glimpse of the author's life in an America, complete with an "Editor's Note" by Ca‐ unusually unguarded and powerful way. mus' daughter Catherine, the author's "Inter‐ In 1960 Albert Camus died in a car accident; leaves"; "Notes and Sketches;" and two letters in‐ found in the wreckage of that accident was the terchanged between Camus and his childhood in‐ hand-written manuscript of his last novel, Le Pre‐ structor, Louis Germain. Although the notes mier Homme(The First Man). At the time of his which Camus left behind suggest that he was death, Camus had fallen out of favor with the planning this work to be a much larger and more French intellectuals. Camus' emphasis on the indi‐ comprehensive project, readers should appreciate vidual conscience, his criticisms of socialism, and its directness and immediacy. his defense of an independent and multicultural Often, Camus stylistically disguised and shad‐ Algeria made him a target from the political left owed his personal beliefs in the earlier works, but and right. -

Thematic Concerns of Albert Camus

International Journal of Research in all Subjects in Multi Languages Vol. 1, Issue:5, August 2013 [Author: Hitendrakumar M. Patel] [Subject: English Literature] (IJRSML) ISSN: 2321 - 2853 Thematic Concerns of Albert Camus HITENDRAKUMAR M. PATEL Assistant Lecturer, Government Science College, Idar. District. Sabarkantha Gujarat (India) Abstract: In this paper, I have focused on the different themes of Camus. His writings reveal the themes of the irrationality of the universe, absurdity of the human existence, the meaninglessness of human life, the importance of the physical world, suicide, decay and death, the nature of human revolt, exile and redemption. As a writer, Camus fashioned a body of literature using a variety of genres and themes to express the breadth and depth of his concerns especially about moral and political issues. He was true to the active and contemplative aspects of life. It is correct that the single work for which Camus is most famous is entitled The Stranger. Meursault, the main character of the novel, exists with a sense of the world and a morality that sets him apart from human society at large. Camus’s first collection Betwixt and Between was published in 1937 while Nuptials was published two years later. The essays in both books largely reflect Camus’s love of Algeria with sensuous descriptions of the landscape and its people. We see Algeria’s landscape and climate informing much of Camus’s work, thematically and symbolically. Exile, Redemption, Separation, Revolt, Absurdity etc are the themes found in Camus’s work. Keywords: The Fall, The Guest, The Plague, The Stranger 1. -

Albert Camus: Resume for Today Barnabas Davis, O.P

Albert Camus: Resume for Today Barnabas Davis, O.P. It has been four years now since a car crash outside Paris took the life of Nobel Prize winner Albert Camus, years which have witnessed conscien tious reappraisals of this unique personality's thought. Last year saw the publication of the first of a trio of his private journals under the title Note books 1935-1942; when the other two volumes appear, we wiU have the complete writings of this young French Algerian and then some .final as sessments may be possible. If this .first volume with its diary-like entries dating from his years at the University of Algiers and including his early writing efforts and war time concern for peace, has done anything for stu dents of his thought, it has directed attention back to his Algerian experi ence. For those who have become acquainted with Camus through his last "I •. 272 DOMINICANA major essay The Rebel (1951), these reflections have the special value of emphasizing the importance of Camus' earlier philosophical position. It would seem appropriate at this time to review the youthful thought of Albert Camus and indicate the general tenor of his writing at the time of his tragic death, along with the areas of discussion current among his com mentators. Camus, who has been called-perhaps too simply-a "Pascal without Christ," rightly ranks with the more controversial of contemporary thinkers. His work, taking the form of both fiction and philosophical essay, utters a pagan message which many observers feel may in time be set beside the great paeans of antiquity. -

Albert Camus at 100 : a Mediterranean Son of France

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Articles School of Business and Humanities 2013-10 Albert Camus at 100 : A Mediterranean Son of France Eamon Maher Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ittbus Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Maher, E., : Albert Camus at 100 : A Mediterranean Son of France, Doctrine & Life, Vol. 63, No. 8, Oct., 2013. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Business and Humanities at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Albert Camus at 100 A Mediterranean Son of France EAMON MAHER HIS YEAR marks the centenary of the birth of one of the world's T finest writers, the French-Algerian Albert Camus (1913-1960). When his father, a pied-noir farm labourer died fighting in the French army during the First World War, Camus' mother, Catherine, was forced to work as a cleaner to provide for her two sons. The younger one, Albert, demonstrated academic talent from an early age and managed to continue in education due to the interest taken in him by two in spirational teachers, Louis Germain and the well-known philosopher, Jean Grenier. He was also awarded scholarships, without which he could not have stayed in school or gone to university.