Bradwell V. State: Some Reflections Prompted by Myra Bradwell's Hard Case That Made "Bad Law"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circuit Circuit

November 2013 Featured In This Issue The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole Address to the Seventh Circuit Bar Association and the Seventh Circuit Judicial Conference Annual Joint TheThe Meeting May 6, 2013, by Senator Richard G. Lugar Through the Eyes of a Juror: A Lawyer's Perspective from Inside the Jury Room, by Karen McNulty Enright The Seventh Circuit Inters "Self-Serving" as an Objection to the Admissibility of Evidence, by Jeffrey Cole My Defining Experience as a Lawyer: Taking a Seventh Circuit Appeal, by Ravi Shankar CirCircuitcuit How 30 Women Changed the Course of the Nation’s Legal and Social History: Commemorating the First National Meeting of Women Lawyers in America, by Gwen Jordan J.D., Ph.D. Common Pleading Deficiencies in RICO Claims, by Andrew C. Erskine You Can Have It Both Ways: Fourth Amendment Standing in the Seventh Circuit, by Christopher Ferro and Marc Kadish RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH A Life Well Lived, by Steven Lubet C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Significant Amendments to Rule 45, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to Take Effect on December 1, 2013, by Jeffrey Cole Sealing Portions of the Appellate Record: A Guide for Seventh Circuit Practitioners, by Alexandra L. Newman Changes &Challenges The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul . 2-4 The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole . -

Self-Reflection Within the Academy: the Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 9 | Number 2 Article 6 7-1-1998 Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Recommended Citation Karin Mika, Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence, 9 Hastings Women's L.J. 273 (1998). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol9/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. & Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika* One does not have to be an ardent feminist to recognize that the con tributions of women in our society have been largely unacknowledged by both history and education. l Individuals need only be reasonably attentive to recognize there is a similar absence of women within the curriculum presented in a standard legal education. If one reads Elise Boulding's The Underside of History2 it is readily apparent that there are historical links between the achievements of women and Nineteenth century labor reform, Abolitionism, the Suffrage Movement and the contemporary view as to what should be protected First Amendment speech? Despite Boulding's depiction, treatises and texts on both American Legal History-and those tracing the development of Constitutional Law-present these topics as distinct and without any significant intersection.4 The contributions of women within all of these movements, except perhaps for the rarely men- *Assistant Director, Legal Writing Research and Advocacy Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. -

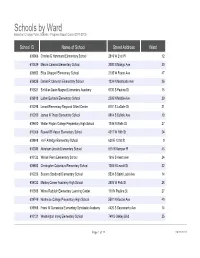

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

An Equal Protection Standard for National Origin Subclassifications: the Context That Matters

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY School of Law 2007 An Equal Protection Standard for National Origin Subclassifications: The Context That Matters Jenny Rivera CUNY School of Law How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/156 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Copyright 0t72007 by Jenny Rivera Readers interested in reprints or copies of this article may contact the Washington Law Review Association which has full license and authority to grant such requests AN EQUAL PROTECTION STANDARD FOR NATIONAL ORIGIN SUBCLASSIFICATIONS: THE CONTEXT THAT MATTERS Jenny Rivera* Abstract: The Supreme Court has stated, "[c]ontext matters when reviewing race-based governmental action under the Equal Protection Clause."' Judicial review of legislative race- based classifications has been dominated by the context of the United States' history of race- based oppression and consideration of the effects of institutional racism. Racial context has also dominated judicial review of legislative classifications based on national origin. This pattern is seen, for example, in challenges to government affirmative action programs that define Latinos according to national origin subclasses. As a matter of law, these national origin-based classifications, like race-based classifications, are subject to strict scrutiny and can only be part of "narrowly tailored measures that further compelling governmental interests., 2 In applying this two-pronged test to national origin classifications, courts have struggled to identify factors that determine whether the remedy is narrowly tailored and whether there is a compelling governmental interest. -

A HISTORICAL COMPARISON of FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT in EARLY NATIVE AMERICA and the US O

42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 10:41:31 SULLIVAN_FINAL (APPROVED).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/21/20 6:54 PM THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING A WOMAN:AHISTORICAL COMPARISON OF FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT IN EARLY NATIVE AMERICA AND THE U.S. SPENSER M. SULLIVAN∗ “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”1 I. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................335 II. REPUBLICAN MOTHERHOOD AND THE “SEPARATE SPHERES” DOCTRINE............................................................................................................................................338 A. Women in the Pre-Revolutionary Era ..............................338 B. The Role of Women in the U.S. Constitution.................339 C. Enlightenment Influences................................................340 D. Republican Mothers.........................................................341 III. WOMEN’S CITIZENSHIP AND THE BARRIERS TO LEGAL EQUALITY....343 A. Defining Female Citizenship in the Founding Era .........343 B. Women’s Ownership of Property–the Feme Covert Conundrum....................................................................344 C. Martin v. Commonwealth: The Rights of the Feme Covert .............................................................................346 D. Bradwell v. Illinois: The Privileges and Immunities of 42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 -

Romer V. Evans: a Legal and Political Analysis

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 15 Issue 2 Article 1 December 1997 Romer v. Evans: A Legal and Political Analysis Caren G. Dubnoff Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Caren G. Dubnoff, Romer v. Evans: A Legal and Political Analysis, 15(2) LAW & INEQ. 275 (1997). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol15/iss2/1 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Romer v. Evans: A Legal and Political Analysis Caren G. Dubnoff* Introduction Despite the Supreme Court's role as final arbiter of the "law of the land," its power to effect social change is limited. For exam- ple, school desegregation, mandated by the Court in 1954, was not actually implemented until years later when Congress and the President finally took action.1 As a result, prayer in public schools, repeatedly deemed illegal by the Court, continues in many parts of the country even today. 2 To some degree, whether the Court's po- * Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, College of the Holy Cross. Ph.D. 1974, Columbia University; A.B. 1964, Bryn Mawr. The author wishes to thank Jill Moeller for her most helpful editorial assistance. 1. Several studies have demonstrated that Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), produced little school desegregation by itself. One of the earliest of these was J.W. PELTASON, FIFTY-EIGHT LONELY MEN: SOUTHERN FEDERAL JUDGES AND SCHOOL DESEGREGATION (1961) (demonstrating how district court judges evaded the decision, leaving school segregation largely in place). -

Tyrone Garner's Lawrence V. Texas

Michigan Law Review Volume 111 Issue 6 2013 Tyrone Garner's Lawrence v. Texas Marc Spindelman Ohio State University's Moritz College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, Sexuality and the Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Marc Spindelman, Tyrone Garner's Lawrence v. Texas, 111 MICH. L. REV. 1111 (2013). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol111/iss6/13 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYRONE GARNER'S LAWRENCE v. TEXASt Marc Spindelman* FLAGRANT CONDUCT: THE STORY OF LAWRENCE V TEXAS. By Dale Carpenter.New York and London: W.W. Norton & Co. 2012. Pp. xv, 284. $29.95. Dale Carpenter's Flagrant Conduct: The Story of Lawrence v. Texas has been roundly greeted with well-earned praise. After exploring the book's understandingof Lawrence v. Texas as a great civil rights victory for les- bian and gay rights, this Review offers an alternative perspective on the case. Builtfrom facts about the background of the case that the book sup- plies, and organized in particular around the story that the book tells about Tyrone Garner and his life, this alternative perspective on Lawrence explores and assesses some of what the decision may mean not only for sexual orientation equality but also for equality along the often- intersecting lines of gender class, and race. -

Territorial Discrimination, Equal Protection, and Self-Determination

TERRITORIAL DISCRIMINATION, EQUAL PROTECTION, AND SELF-DETERMINATION GERALD L. NEUMANt TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................... 262 I. A FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING GEOGRAPHICAL DISCRIMINATIONS .................................. 267 A. A Page of History .......................... 267 B. A Volume of Logic ......................... 276 1. Fundamental Rights and Equal Protection .. 276 2. The Need for Scrutiny of Geographical Dis- crimination: With Apologies for Some Jargon 287 3. General Position-Random Intrastate Varia- tions ................................. 294 4. First Special Position-Independent Action of Political Subdivisions .................... 295 a. The Single Decisionmaker Fallacy ..... 296 b. The Special Status of Political Subdivi- sions ............................. 301 c. Accommodating Self-Determination and Equal Protection ................... 309 5. Second Special Position-Interstate Variations 313 a. The Choice of Law Problem .......... 314 b. The Privileges and Immunities Perspec- tive .............................. 319 c. Fundamental Rights Equal Protection and Choice of Law ................. 328 t Assistant Professor of Law, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This article is dedicated to Archibald Cox, who taught me to prefer reason to logic. Earlier versions of this article were presented to faculty groups at Harvard Law School, The University of Chicago Law School, and the University of Pennsylvania Law School in February and October of 1983. I thank all those present for their inci- sive comments. I am especially grateful for comments and advice from my colleagues Regina Austin, Stephen Burbank, Michael Fitts, Seth Kreimer, Harold Maier, Curtis Reitz, Clyde Summers, Akhil Amar, Harold Koh, and Ed Baker, whose patience was inexhaustible. I also thank Mrs. Margaret Ulrich for her extraordinary skill and dedi- cation, which made control of this unwieldy text possible. (261) 262 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

The Poor As a Suspect Class Under the Equal Protection Clause: an Open Constitutional Question

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2010 The oP or as a Suspect Class under the Equal Protection Clause: An Open Constitutional Question Henry Rose Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Civil Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Henry, The oorP as a Suspect Class under the Equal Protection Clause: An Open Constitutional Question, 34 Nova Law Review 407 (2010) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POOR AS A SUSPECT CLASS UNDER THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE: AN OPEN CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTION HENRY ROSE* (ABSTRACT) Both judges and legal scholars assert that the United States Supreme Court has held that the poor are neither a quasi-suspect nor a suspect class under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Unit- ed States Constitution. They further assert that this issue was decided by the Supreme Court in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973). It is the thesis of this article that the Supreme Court has not yet decided whether the poor are a quasi-suspect or a suspect class under Equal Protec- tion. In fact, the majority in San Antonio Independent School District v. Ro- driquez found that the case involved no discrete discrimination against the poor. Whether the poor should constitute a quasi-suspect or suspect class under Equal Protection remains an open constitutional question. -

Fundamental Personal Rights: Another Approach to Equal Protection

Fundamental Personal Rights: Another Approach to Equal Protection The recent history of the United States Supreme Court is often said to be marked by a decisive turning point in the method and substance of constitutional adjudication.' Between 1934 and 1937 the Court began to abandon most of the reasoning of and the policies embodied in "sub- stantive due process," 2 and by 1941 the old doctrine was explicitly repudiated." The pre-1937 Court's approach to interpreting the vague provisions of the due process clauses may best be characterized as a "balancing" of the burdens imposed on a person's life, liberty or property by governmental regulation against the governmental justi- fications for the burdens. In many of these substantive due process cases, the Court found the regulation in question insufficiently justified and therefore unconstitutional. 4 In many other cases, however, the pre-1937 C6urt found the regulation to be a reasonable exercise of governmental power.5 One of the primary objections to the substantive due process ap- proach was that the Court substituted its judgment of the wisdom of legislation for that of the popularly elected branches of government.6 In response to this criticism, the post-1937 Court developed an approach 1 E.g., McCloskey, Economic Due Process and the Supreme Court: An Exhumation and Reburial, 1962 Sup. Or. Rzv. 34; Stern, The Problems of Yesteryear-Commerce and Due Process,4 VAND. L. REv. 446 (1951). 2 See West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379 (1937); Nebbia v. New York, 291 U.S. 502 (1934). -

Obergefell V. Hodges: Same-Sex Marriage Legalized

Obergefell v. Hodges: Same-Sex Marriage Legalized Rodney M. Perry Legislative Attorney August 7, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44143 Obergefell v. Hodges: Same-Sex Marriage Legalized Summary On June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Obergefell v. Hodges requiring states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and to recognize same-sex marriages that were legally formed in other states. In doing so, the Court resolved a circuit split regarding the constitutionality of state same-sex marriage bans and legalized same-sex marriage throughout the country. The Court’s decision relied on the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection and due process guarantees. Under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, state action that classifies groups of individuals may be subject to heightened levels of judicial scrutiny, depending on the type of classification involved or whether the classification interferes with a fundamental right. Additionally, under the Fourteenth Amendment’s substantive due process guarantees, state action that infringes upon a fundamental right—such as the right to marry—is subject to a high level of judicial scrutiny. In striking down state same-sex marriage bans as unconstitutional in Obergefell, the Court rested its decision upon the fundamental right to marry. The Court acknowledged that its precedents have described the fundamental right to marry in terms of opposite-sex relationships. Even so, the Court determined that the reasons why the right to marry is considered fundamental apply equally to same-sex marriages. The Court thus held that the fundamental right to marry extends to same- sex couples, and that state same-sex marriage bans unconstitutionally interfere with this right. -

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow University of New Hampshire School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ann Bartow, "Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys," 11 WM. & MARY J. WOMEN & L. 221 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm.