FOLK-SONGS of ASSAM Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O G BAAJAA GAAJAA OPEN STAGE 1 – AAN Date: Feb 5, 2010 GAN Time Artiste Vocal/Instrument Genre/Notes 11 Am-11.30 Am Unmesh

BAAJAA GAAJAA OPEN STAGE 1 – AANGAN Date: Feb 5, 2010 Time Artiste Vocal/Instrument Genre/Notes Unmesh Khaire(harmonium)+Abhim 11 am-11.30 am anyu Herlekar (tabla) Harmonium solo Hindustani Classica 11.30 am-12.15 pm Darpana Academy Various Folk music of Gujarat 12.15 pm- 12.30 pm Bajrang Vasudeo Vocal Folk music of Maharashtra 12.30 pm- 1 pm Prakash Shejwal Pakhawaj solo Hindustani Classica Vocal: Dhananjay Hegde, Anant Terdal, Suvarny Nayak, Shantheri Kamath Tabla: T. Ranga Pai Harmonium: Shankar Shenoy Sitar:Shruti Dasarapadagalu-Kannada religious and 2 pm-2.45 pm Kamath Vocal folk songs Snehasish Mozumdar (mandolin)+Partha Sarathi 2.45 pm-3.30 pm Mukherjee (tabla) Mandolin Hindustani Classica 3.30 pm-4.15 pm Shahir Rangrao Patil, Rashtriya Shahiri, Bhedik 4.15 pm-5 pm Shahir Mahadeo Budake Shahiri and Dhangari ov Folk music of Maharashtra Arnab Chakrabarty (sarod)+Partha Sarathi 5 pm-5.45 pm Mukherjee (tabla) Sarod Hindustani Classica Dnyani Bhajan Mandal - Mahadeobuwa Shahabadkar (Koli) and 5.45 pm – 6.30 pm ensemble Vocal Religious TOTAL OPEN STAGE 1 Date: Feb 6, 2010 Time Artiste Vocal/Instrumental Genre/Notes 11 am-11.30 am 11.30 am-12.15 pm Milind Date Instrumental Fusion Band Marathi Bhav Sangeet played by T. Ranga Pai (Violin) and Shruti Kamath (Sitar) Tabla: 12.15 pm- 1 pm Shantanu Kinjavdekar Violin and sitar Popular music Hiros Nakagawa (bansuri) + 2 pm-2.45 pm Prafull Athalye (tabla) Bansuri Hindustani Classical 2.45 pm-3.15 pm Child artiste- Rajasthan Various Folk music of Rajasthan S. -

Current Affairs 40 40 MCQ of Computer 52

MONTHLY ISSUE - MAY - 2015 CurrVanik’s ent Affairs Banking | Railway | Insurance | SSC | UPSC | OPSC | PSU A Complete Magazine for all Competitive ExaNEmsW SECTIONS BLUE ECONOMY Vanik’s Page Events of the month 200 Updated MCQs 100 One Liners 40 MCQs on Computers 100 GK for SSC & Railway Leading Institute for Banking, Railway & SSC New P u b l i c a t i o n s Vanik’s Knowledge Garden VANIK'S PAGE Cultural Dances In India Andhra Pradesh Ÿ Ghumra Ÿ Kuchipudi Ÿ Karma Naach Ÿ Kolattam Ÿ Keisabadi Arunachal Pradesh Puducherry Ÿ Bardo Chham Ÿ Garadi Assam Punjab Ÿ Bihu dance Ÿ Bhangra Ÿ Jumur Nach Ÿ Giddha Ÿ Bagurumba Ÿ Malwai Giddha Ÿ Ali Ai Ligang Ÿ Jhumar Chhattisgarh Ÿ Karthi Ÿ Panthi Ÿ Kikkli Ÿ Raut Nacha Ÿ Sammi Ÿ Gaur Maria Dance Ÿ Dandass Gujarat Ÿ Ludi Ÿ Garba Ÿ Jindua Ÿ Padhar Rajasthan Ÿ Raas Ÿ Ghoomar Ÿ Tippani Dance Ÿ Kalbelia Himachal Pradesh Ÿ Bhavai Ÿ Kinnauri Nati Ÿ Tera tali Ÿ Namgen Ÿ Chirami Karnataka Ÿ Gair Ÿ Yakshagana Sikkim Ÿ Bayalata Ÿ Singhi Chham Ÿ Dollu Kunitha Tamil Nadu Ÿ Veeragaase dance Ÿ Bharatanatya Kashmir Ÿ Kamandi or Kaman Pandigai Ÿ Dumhal Ÿ Devarattam Lakshadweep Ÿ Kummi Ÿ Lava Ÿ Kolattam Madhya Pradesh Ÿ Karagattam or Karagam Ÿ Tertal Ÿ Mayil Attam or Peacock dance Ÿ Charkula Ÿ Paampu attam or Snake Dance Ÿ Jawara Ÿ Oyilattam Ÿ Matki Dance Ÿ Puliyattam Ÿ Phulpati Dance Ÿ Poikal Kudirai Attam Ÿ Grida Dance Ÿ Bommalattam Ÿ Maanch Ÿ Theru Koothu Maharashtra Tripura Ÿ Pavri Nach Ÿ Hojagiri Ÿ Lavani West Bengal Manipur Ÿ Gambhira Ÿ Thang Ta Ÿ Kalikapatadi Ÿ Dhol cholom Ÿ Nacnī Mizoram Ÿ Alkap Ÿ Cheraw Dance Ÿ Domni Nagaland Others Ÿ Chang Lo or Sua Lua Ÿ Ghoomar (Rajasthan, Haryana) Odisha Ÿ Koli (Maharashtra and Goa) Ÿ Ghumura Dance Ÿ Padayani (Kerala) Ÿ Ruk Mar Nacha (& Chhau dance) North India Ÿ Goti Pua Ÿ Kathak Ÿ Nacnī Ÿ Odissi Ÿ Danda Nacha Ÿ Baagh Naach or Tiger Dance Ÿ Dalkhai Ÿ Dhap MAGAZINE FOR THE MONTH OF MAY - 2015 VANIK’S MAGAZINE FOR THE MONTH OF MAY - 2015 B – 61 A & B, Saheed Nagar & Plot-1441, Opp. -

Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music"

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research John Jay College of Criminal Justice 2000 The Construction of a Diasporic Tradition: Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music" Peter L. Manuel CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/jj_pubs/335 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] VOL. 44, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 2000 The Construction of a Diasporic Tradition: Indo-Caribbean "Local Classical Music" PETER MANUEL / John Jay College and City University of New York Graduate Center You take a capsule from India leave it here for a hundred years, and this is what you get. Mangal Patasar n recent years the study of diaspora cultures, and of the role of music therein, has acquired a fresh salience, in accordance with the contem- porary intensification of mass migration and globalization in general. While current scholarship reflects a greater interest in hybridity and syncretism than in retentions, the study of neo-traditional arts in diasporic societies may still provide significant insights into the dynamics of cultural change. In this article I explore such dynamics as operant in a unique and sophisticated music genre of East Indians in the Caribbean.1 This genre, called "tan-sing- ing," has largely resisted syncretism and creolization, while at the same time coming to differ dramatically from its musical ancestors in India. Although idiosyncratically shaped by the specific circumstances of the Indo-Caribbean diaspora, tan-singing has evolved as an endogenous product of a particu- lar configuration of Indian cultural sources and influences. -

Free Rajasthani Music

Free rajasthani music click here to download Rajasthani stock music and background music 38 stock music clips and loops. Production music starting at $ Download and buy high quality tracks. Why download Rajasthani MP3 songs when you can listen to the latest Rajasthani songs online! Meera - Rajasthani Lok Bhajan Raj Music Masuda. rajasthani music page 4. Rajasthani Music Royalty-free Music, SFX, and Loops. Filter your results. Music, Sound Effects, Loops, All. All. Music; Sound Effects. Rajasthan Folk - Music of The Desert - Langas & Manganiars | Audio Jukebox | Folk | Vocal | - Duration: 8tracks radio. Online, everywhere. - stream 5 rajasthani playlists including Indian, Gulabi, and Taraf de Haïdouks music from your desktop or mobile device. Discover Rajasthani Music. Play Rajasthani Radio. Genres. ComedyCompilationsDevotionalFolkHoli SongsMovie SongsPopVivah Geet. Albums. CKRS. Free Download Rajasthani Single Remix Rajasthani Single RemixMusic Mp3 Songs, Rajasthani Mp3 Songs, From www.doorway.ru Royalty free rajasthani Music, Sound Effects, Stock Footage and Photos for use in multimedia projects. Download stock music immediately for film and. To download top 50 rajasthani folk songs for free, all you need is. Rajasthani Songs Download New Top Rajasthani Songs Albums www.doorway.ru free music Rajasthani Songs download album Rajasthani Songs djjohal latest. Veena Music,Rajasthani Songs Download,Marwari Songs Download,Rajasthani Music,Marwari Music,Downloads,MP3 Music Downlaod,MP3 Songs Downlaod. Top rajasthani artists: Musafir, Ila Arun, Seema Mishra, The Dharohar Project, Vishwa Mohan Bhatt Do you know anything about this type of music? Start the. See a rich collection of stock images, vectors, or photos for rajasthani music you can buy on Shutterstock. Explore quality images, photos, art & more. -

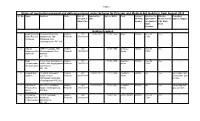

Status of Application Received and Deficiency Found Under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Sr

Page 1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Sr. No. Name Address State Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, SO- Andhra 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o Narsipatnam, Mdl- Pradesh 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam -531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, Mdl- Andhra 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Chandralapadu, Dist- Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near Bandipalem- Andhra 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Vill/Po, Mdl-Jaggayyapeta, Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Dist-Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, Ambedkar Andhra 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Nagar, Arilova, Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Chinagadilimandal Dist- pension. Visakhapatnam-530 040. 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, Madhura Andhra 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Nagar, Visakhapatnam- Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. 530 016. Narasimhulu Page 2 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, Andhra 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, Pradesh 31/08/2018 1500/- J. -

Rajasthan Tour Itinerary V. 5

Exclusive Tour of the Music, Dance and Spiritual Worlds of Rajasthan, India 2016 With Yuval Ron & Sajida Ben-Tzur Take a journey full of rare musical encounters, exquisite dancing, sacred Sufi shrines, stunning landscapes, temples, desert tribal parties and the festive celebrations of Rajasthan 14 glorious days - February 14-27, 2016 The sights of India’s impressive landscapes are the glorious backdrop for a special excursion that enables an intimate, unique introduction to India through its tribal musical culture and the special inhabitants of the Rajasthan desert. Rajasthan (Raj – royal, sthan – land/state) is one of the most colorful states in India. It is a desert region abounding in classical and ancient traditions, where palaces, temples, fortresses and royalty exist alongside villages and tribes. Music in India, and especially in Rajasthan, is a principal part of religious rituals setting the tone for holidays and wedding ceremonies. This music, played for kings when they went off to battle, accompanies the Sufi festivities and provides entertainment for the high society. Bringing the various religions and classes together, the music of Rajasthan opens a door to the fascinating cultural worlds that are the focus and inspiration for this special journey. Sajida Ben-Tzur, our tour guide, is a dancer of Kathak classical Indian and the Rajasthani folk dance traditions, an Indian Chef and the daughter of a Sufi Sheikh from Rajasthan. Sajida (pronounced SAJ-DA) has met and worked with many of the most exceptional musicians in this region. This tour facilitates a personal connection with Rajasthan’s landscapes and people through the ears, the eyes and especially the heart! Feb 14-15, 2016 - Day 1-2: Flight to India Depart on a flight of your choice to Delhi, India. -

Music Industry Workshop

Third United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries Proceedings of the Youth Forum MUSIC INDUSTRY WORKSHOP European Parliament Brussels, Belgium 19 May 2001 UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2003 NOTE The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. All data are provided without warranty of any kind and the United Nations does not make any representation or warranty as to their accuracy, timeliness, completeness or fitness for any particular purposes. UNCTAD/LDC/MISC.82 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This publication is the outcome of the proceedings of the Youth Forum Music Industry Workshop, a parallel event organized on 19 May 2001 during the Third United Nations Conference on the Least Developed Countries, held in the European Parliament in Brussels. Ms. Zeljka Kozul-Wright, the Youth Forum Coordinator of the Office of the Special Coordinator for LDCs, prepared this publication. Lori Hakulinen-Reason and Sylvie Guy assisted with production and Diego Oyarzun-Reyes designed the cover. ii CONTENTS Pages OPENING STATEMENTS Statement by Mr. Rubens Ricupero ............................................................................ 1 Statement by H.E. Mr. Mandisi B. Mpahlwa ............................................................... 5 Statement by Ms. Zeljka Kozul-Wright......................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION Challenges and prospects in the music industry for developing countries by Zeljka Kozul-Wright................................................................................................. -

Status of Application Received and Deficiency Found Under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Onwards

1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 onwards Sr. No. Name Address Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o SO-Narsipatnam, 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Mdl-Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam - 531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Mdl- 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Chandralapadu, Dist-Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Bandipalem- 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Vill/Po, Mdl- Jaggayyapeta, Dist- Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Ambedkar Nagar, 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Arilova, pension. Chinagadilimandal Dist- Visakhapatnam- 530 040. 2 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Madhura Nagar, 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. Visakhapatnam- Narasimhulu 530 016. 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, 31/08/2018 1500/- J. Srinivasarao Dist-Krishna- 521 225 7 Tatineni Surya Near Mahalakshmi 549 15-06-2018 01-01-1944 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. -

Ethnomusicology a Very Short Introduction

ETHNOMUSICOLOGY A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION Thimoty Rice Sumário Chapter 1 – Defining ethnomusicology...........................................................................................4 Ethnos..........................................................................................................................................5 Mousikē.......................................................................................................................................5 Logos...........................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 A bit of history.................................................................................................................9 Ancient and medieval precursors................................................................................................9 Exploration and enlightenment.................................................................................................10 Nationalism, musical folklore, and ethnology..........................................................................10 Early ethnomusicology.............................................................................................................13 “Mature” ethnomusicology.......................................................................................................15 Chapter 3........................................................................................................................................17 Conducting -

Evolution and Assessment of South Asian Folk Music: a Study of Social and Religious Perspective

British Journal of Arts and Humanities, 2(3), 60-72, 2020 Publisher homepage: www.universepg.com, ISSN: 2663-7782 (Online) & 2663-7774 (Print) https://doi.org/10.34104/bjah.020060072 British Journal of Arts and Humanities Journal homepage: www.universepg.com/journal/bjah Evolution and Assessment of South Asian Folk Music: A Study of Social and Religious Perspective Ruksana Karim* Department of Music, Faculty of Arts, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. *Correspondence: [email protected] (Ruksana Karim, Lecturer, Department of Music, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh) ABSTRACT This paper describes how South Asian folk music figured out from the ancient era and people discovered its individual form after ages. South Asia has too many colorful nations and they owned different culture from the very beginning. Folk music is like a treasure of South Asian culture. According to history, South Asian people established themselves here as a nation (Arya) before five thousand years from today and started to live with native people. So a perfect mixture of two ancient nations and their culture produced a new South Asia. This paper explores the massive changes that happened to South Asian folk music which creates several ways to correspond to their root and how they are different from each other. After many natural disasters and political changes, South Asian people faced many socio-economic conditions but there was the only way to share their feelings. They articulated their sorrows, happiness, wishes, prayers, and love with music, celebrated social and religious festivals all the way through music. As a result, bunches of folk music are being created with different lyric and tune in every corner of South Asia. -

Pension and Medical Aid (27-July 2019).Pdf

Page 1 Status of application received and deficiency found under Scheme for Pension and Medical Aid to Artists from August 2018 Sr. No. Name Address State Date of Application Date of Birth Field Annual / Whether the Whether Remark of Receipit & Date Monthly applicant is Recommende SCZCC, Nagpur. Inward No. Income receipant of d by State State Govt. Pension. Andhra Pradesh 1 Repallichakrad Po-Kusarlapudi, SO- Andhra 507 15-06-2018 01-01-1956 Actor 25000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - harao Rao S/o Narsipatnam, Mdl- Pradesh 07/08/2018 1500/- Venkayya Rolugunta, Dist- Visakhapatnam -531 118. 2 Velpula Vill/Po-Trulapadu, Mdl- Andhra 526 01-01-1956 Destitutu 42000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Nagamma W/o Chandralapadu, Dist- Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- Papa Rao Krishna- 521 183. 3 Meka H. No. Near Bandipalem- Andhra 527 01-01-1956 Destitutu 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes. - Venkateswarlu Vill/Po, Mdl-Jaggayyapeta, Pradesh 10/08/2018 Artists 1500/- S/o Mamadasu Dist-Krishna- 521 178. 4 Yerapati S/o 13-430/A, Ambedkar Andhra 542 09-07-2018 11-12-1955 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not Eligible. Not Apparao Nagar, Arilova, Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists getting state govt. Chinagadilimandal Dist- pension. Visakhapatnam-530 040. 5 Kasa Surya 49-27-61/1, Madhura Andhra 543 09-07-2018 01-07-1950 Destitutu 48000/- No Yes. Not getting state Prakasa Rao Nagar, Visakhapatnam- Pradesh 31/08/2018 Artists govt. pension. S/o Lt. 530 016. Narasimhulu 6 Jalasutram 13-138, Gollapudi, Andhra 544 28-02-1957 Drama Artists 48000/- Yes. Rs. Yes - Vyshnavi W/o Karakatta, Pradesh 31/08/2018 1500/- J. -

Study Materials for Six Months Special Training Programme On

Six month Special Training Progaramme on Elementary Education for Primary School Teachers having B.Ed/B.Ed Special Edn/D.Ed (Special Edn.) (ODL Mode) Art Education, Work Education, Health & Physical Education West Bengal Board of Primary Education, Acharya Prafulla Chandra Bhaban D.K. - 7/1, Sector - 2 Bidhannagar, Kolkata - 700091 i West Bengal Board of Primary Education First edition : March, 2015 Neither this book nor any keys, hints, comments, notes, meanings, connotations, annotations, answers and solutions by way of questions and answers or otherwise should be printed, published or sold without the prior approval in writing of the President, West Bengal Board of Primary Education. Publish by Prof. (Dr) Manik Bhattacharyya, President West Bengal Board of Primary Education Acharyya Prafulla Chandra Bhavan, D. K. - 7/1, Sector - 2 Bidhannagar, Kolkata - 700091 ii Forewords It gives me immense pleasure in presenting the materials of Art, Health, Physical Education & Work Education for Six Month Special Training Programme in Elementary Education for the elementary school teachers in West Bengal, having B. Ed. / B. Ed. (Special Education)/ D. Ed. (Special Education). The materials being presented have been developed on the basis of the guidelines and syllabus of the NCTE. Care has been taken to make the presentation flawless and in perfect conformity with the guidelines of the NCTE. Lesson-units and activities given here are not exhaustive. Trainee-teachers are at liberty to plan & develop their own knowledge and skills through self learning under the guidance of the counselors and use of their previously acquired knowledge and skill of teaching. This humble effort will be prized, if the materials, developed here in this Course-book, are used by the teachers in the real classroom situations for the development of the four skills – Listening, Speaking, Reading and Writing of the elementary school children .