The Concept of Tala in Semi-Classical Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

The Role of Radio in Promoting the Folk and Sufiana Music in the Kashmir Valley

Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. XII, Issue No. 23, October-2016, ISSN 2230-7540 The Role of Radio in Promoting the Folk and Sufiana Music in the Kashmir Valley Afshana Shafi* Research Scholar, M.D.U., Rohtak, Haryana Abstract – In this Research work the Researcher reveals the role of All India Radio Srinagar in promoting the folk and sufiana music of Kashmir. Sufiana music is also known as the classical music of Kashmir. There was a time when the radio was considered to be a kind of entertainment only. At that sphere of time, All India Radio Kashmir was also touching the sky from its potential. Radio was widely heard among masses. Radio plays a significant role in the promoting of kashmiri music and the musicians of Kashmir. In this research work the researcher has written about role of Radio in Kashmiri music and in the success of kashmiri musicians. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - As you have heard very different stories about Kashmir evening, in this way Radio Kashmir has been a major yet, but apart from it, Kashmir is full of colors‘. So, let‘s contributor to promoting folk music of Kashmir. talk about those same colors of Kashmir. Kashmiri Music has created a name throughout the world, yes I As the people of Kashmir, living in remote areas, do am talking about sufiana music but before that we will not have access the other source of information and talk about the folk music of Kashmir. The chief source of entertainment, apart from the limited local traditional entertainment is only Music, and an important element activities, for the majority of the people,but as its said governing popularity or unpopularity of the service change is the law of nature but inspite of this radio ―points out H.R Luthra . -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Hindustani Classic Music

HINDUSTANI CLASSIC MUSIC: Junior Grade or Prathamik : Syllabus : No theory exam in this grade Swarajnana Talajnana essential Ragajnana Practicals: 1. Beginning of swarabyasa - in three layas 2. 2 Swaramalikas 5 Lakshnageete Chotakyal Alap - 4 ragas Than - 4 Drupad - should be practiced 3. Bhajan - Vachana - Dasapadas 4. Theental, Dadara, Ektal (Dhruth), Chontal, Juptal, Kheruva Talu - Sam-Pet-Husi-Matras - should practice Tekav. 5. Swarajnana 6. Knowledge of the words - nada, shruthi, Aroha, Avaroha, Vadi - Samvedi, Komal - Theevra - Shuddha - Sasthak - Ganasamay - Thaat - Varjya. 7. Swaralipi - should be learnt. Senior Grade: (Madhyamik) Syllabus : Theory: 1. Paribhashika words 2. Sound & place of emergence of sound 3. The practice of different ragas out of “thaat” - based on Pandith Venkatamukhi Mela System 4. To practice ragalaskhanas of different ragas 5. Different Talas - 9 (Trital, Dadra, Jup, Kherva, Chantal, Tilawad, Roopak, Damar, Deepchandi) explanation of talas with Tekas. 6. Chotakhyal, Badakhyal, Bhajan, Tumari, Geethprakaras - Lakshanas. 7. Life history of Jayadev, Sarangdev, Surdas, Purandaradas, Tansen, Akkamahadevi, Sadarang, Kabeer, Meera, Haridas. 8. Knowledge of musical instrument Practicals: 1. Among 20 ragas - Chotakhyal in each 2. Badakhyal - for 10 ragas (Bhoopali, Yamani, Bheempalas, Bageshree, Malkonnse, Alhaiah Bilawal, Bahar, Kedar, Poorvi, Shankara. 3. Learn to sing one drupad in Tay, Dugun & Changun - one Damargeete. VIDHWAN PROFICIENCY Syllabus: Theory 1. Paribhashika Shabdas. 2. 7 types of Talas - their parts (angas) 3. Tabala bol - Tala Jnana, Vilambitha Ektal, Jumra, Adachontal, Savari, Panjabi, Tappa. 4. Raga lakshanas of Bhairav, Shuddha Sarang, Peelu, Multhani, Sindura, Adanna, Jogiya, Hamsadhwani, Gandamalhara, Ragashree, Darbari, Kannada, Basanthi, Ahirbhairav, Todi etc., Alap, Swaravisthara, Sama Prakruthi, Ragas criticism, Gana samay - should be known. -

Hindustani Percussion Syllabus Levels

Level 1 IndianRaga Hindustani Percussion Curriculum Practical Sample Question Set 1. Basic strokes: individual & combination 1. Play the basic 2. Basic phrases: at the discretion of the teacher phrases with Suggested: Thirakita, thirakitathaka, some variations – thirakitathaka tha gegethita, 3. Phrases with variations: at the discretion of the thirakitathaka etc teacher as advised by Suggested: Gege thita gege nana, dhadha thita teacher dhadha thina 2. Play teental theka Dha dha thirakita dha dha thina etc. in 3 speeds and 4. Teental basic pattern (Theka) in 3 speeds recite with beat 5. Basic Qaida, Rhela based patterns : at the 3. Play a small qaida discretion of the teacher 4. Tell us about the different parts of the tabla and Theory Requirements what they are 1. Building blocks of tala and counting made of 2. Recitation of all the above practical requirements Evaluation Adherence to Laya (proper tempo, rhythm), Posture, precision of strokes as well as proper recitation. Level 2 IndianRaga Hindustani Percussion Curriculum Practical & Theory Requirements Sample Questions set 1. Tala dadra, roopak, jhaptaal – recite and play in 1. Play thekas of 3 speeds Dadra, roopak 2. 3 finger tirkit (& more complex thirkit phrases) and Teental in 3 3. Further development of basic phrases from speeds level 1 2. Play some thirkit 4. 2 qaidas with 3 variations each – thi ta, thirakita based phrases based and more at the discretion of teacher 3. Play a qaida based 5. 3 thihais and 2 simple tukdas in Teental in thi ta with some variations 4. Play some thihais Evaluation in Teental Adherence to Laya (proper tempo, rhythm), Posture, 5. -

Harmonic Progressions of Hindi Film Songs Based on North Indian Ragas

UNIVERSITI PUTRA MALAYSIA HARMONIC PROGRESSIONS OF HINDI FILM SONGS BASED ON NORTH INDIAN RAGAS WAJJAKKARA KANKANAMALAGE RUWIN RANGEETH DIAS FEM 2015 40 HARMONIC PROGRESSIONS OF HINDI FILM SONGS BASED ON NORTH INDIAN RAGAS UPM By WAJJAKKARA KANKANAMALAGE RUWIN RANGEETH DIAS COPYRIGHT Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, © in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 All material contained within the thesis, including without limitation text, logos, icons, photographs and all other artwork, is copyright material of Universiti Putra Malaysia unless otherwise stated. Use may be made of any material contained within the thesis for non-commercial purposes from the copyright holder. Commercial use of material may only be made with the express, prior, written permission of Universiti Putra Malaysia. Copyright © Universiti Putra Malaysia UPM COPYRIGHT © Abstract of thesis presented of the Senate of Universiti Putra Malaysia in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy HARMONIC PROGRESSIONS OF HINDI FILM SONGS BASED ON NORTH INDIAN RAGAS By WAJJAKKARA KANKANAMALAGE RUWIN RANGEETH DIAS December 2015 Chair: Gisa Jähnichen, PhD Faculty: Human Ecology UPM Hindi film music directors have been composing raga based Hindi film songs applying harmonic progressions as experienced through various contacts with western music. This beginning of hybridization reached different levels in the past nine decades in which Hindi films were produced. Early Hindi film music used mostly musical genres of urban theatre traditions due to the fact that many musicians and music directors came to the early film music industry from urban theatre companies. -

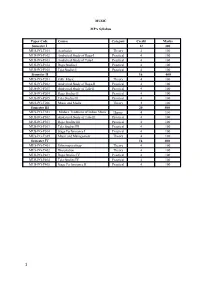

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

K-4 Curriculum Guide

India and its Music Classical North Indian music comes began thousands of years ago before the Christian Era in world history. Since this musical tradition is taught by an oral method (spoken or sung), instead of written, there were not reliable written records of the music except in very ancient books called the Vedas. These were books that recorded stories and hymns and prescriptions for how to behave according to the Hindu religion and were written 3,200 to 4,000 years ago. Some people believe they were written thousands of years earlier, and scholars debate this subject. India: Home to the World’s Great Religions In India many of the world’s great religions got their start. These would include Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and the Sikh religion. Also there are Indian Christians, and Islam is an important religion in the north of India. For many centuries Islamic culture had a big influence on music and mingled with the original music of India that existed before the Moslems conquered India. The result is a music that took elements of Islamic music from Persia, Turkey and Afghanistan and blended with the original music of India to become Hindustani music – the classical music of north India. The Hindu religion’s legends and mythology have many gods and goddesses, and these gods and goddesses are thought to be aspects of the One God Vishnu. Saraswati, Goddess of art, music, and learning One important goddess to Indian artists, scholars and musicians is Saraswati who is the goddess of art, music and learning. Mohandas K. -

Musical Explorers Is Made Available to a Nationwide Audience Through Carnegie Hall’S Weill Music Institute

Weill Music Institute Teacher Musical Guide Explorers My City, My Song A Program of the Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Hall for Students in Grades K–2 2016 | 2017 Weill Music Institute Teacher Musical Guide Explorers My City, My Song A Program of the Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Hall for Students in Grades K–2 2016 | 2017 WEILL MUSIC INSTITUTE Joanna Massey, Director, School Programs Amy Mereson, Assistant Director, Elementary School Programs Rigdzin Pema Collins, Coordinator, Elementary School Programs Tom Werring, Administrative Assistant, School Programs ADDITIONAL CONTRIBUTERS Michael Daves Qian Yi Alsarah Nahid Abunama-Elgadi Etienne Charles Teni Apelian Yeraz Markarian Anaïs Tekerian Reph Starr Patty Dukes Shanna Lesniak Savannah Music Festival PUBLISHING AND CREATIVE SERVICES Carol Ann Cheung, Senior Editor Eric Lubarsky, Senior Editor Raphael Davison, Senior Graphic Designer ILLUSTRATIONS Sophie Hogarth AUDIO PRODUCTION Jeff Cook Weill Music Institute at Carnegie Hall 881 Seventh Avenue | New York, NY 10019 Phone: 212-903-9670 | Fax: 212-903-0758 [email protected] carnegiehall.org/MusicalExplorers Musical Explorers is made available to a nationwide audience through Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute. Lead funding for Musical Explorers has been provided by Ralph W. and Leona Kern. Major funding for Musical Explorers has been provided by the E.H.A. Foundation and The Walt Disney Company. © Additional support has been provided by the Ella Fitzgerald Charitable Foundation, The Lanie & Ethel Foundation, and -

12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, Vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, Tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, Harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, Tanpuras

From left to right: Pandit Anindo Chatterjee, Shampa Bhattacharya, Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, Michael Harrison, Kedar Naphade Photo credit: Ira Meistrich, edited by Tina Psoinos 12 NI 6340 MASHKOOR ALI KHAN, vocals ANINDO CHATTERJEE, tabla KEDAR NAPHADE, harmonium MICHAEL HARRISON & SHAMPA BHATTACHARYA, tanpuras TRANSCENDENCE Raga Desh: Man Rang Dani, drut bandish in Jhaptal – 9:45 Raga Shahana: Janeman Janeman, madhyalaya bandish in Teental – 14:17 Raga Jhinjhoti: Daata Tumhi Ho, madhyalaya bandish in Rupak tal, Aaj Man Basa Gayee, drut bandish in Teental – 25:01 Raga Bhupali: Deem Dara Dir Dir, tarana in Teental – 4:57 Raga Basant: Geli Geli Andi Andi Dole, drut bandish in Ektal – 9:05 Recorded on 29-30 May, 2015 at Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY Produced and Engineered by Adam Abeshouse Edited, Mixed and Mastered by Adam Abeshouse Co-produced by Shampa Bhattacharya, Michael Harrison and Peter Robles Sponsored by the American Academy of Indian Classical Music (AAICM) Photography, Cover Art and Design by Tina Psoinos 2 NI 6340 NI 6340 11 at Carnegie Hall, the Rubin Museum of Art and Raga Music Circle in New York, MITHAS in Boston, A True Master of Khayal; Recollections of a Disciple Raga Samay Festival in Philadelphia and many other venues. His awards are many, but include the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar by the Sangeet Natak Aka- In 1999 I was invited to meet Ustad Mashkoor Ali Khan, or Khan Sahib as we respectfully call him, and to demi, New Delhi, 2015 and the Gandharva Award by the Hindusthan Art & Music Society, Kolkata, accompany him on tanpura at an Indian music festival in New Jersey.