Sonic Performativity: Analysing Gender in North Indian Classical Vocal Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Modeling a Performance in Indian Classical Music: Multinomial

Archive of Cornell University e-library; arXiv:0809.3214v1[cs.SD][stat.AP]. http://arxiv.org/abs/0809.3214 A Statistical Approach to Modeling Indian Classical Music Performance 1Soubhik Chakraborty*, 2Sandeep Singh Solanki, 3Sayan Roy, 4Shivee Chauhan, 5Sanjaya Shankar Tripathy and 6Kartik Mahto 1Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 2, 3, 4, 5,6Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India Email:[email protected](S.Chakraborty) [email protected] (S.S. Solanki) [email protected](S. Roy) [email protected](S. Chauhan) [email protected] (S.S.Tripathy) [email protected] *S. Chakraborty is the corresponding author (phone: +919835471223) Words make you think a thought. Music makes you feel a feeling. A song makes you feel a thought. -------- E. Y. Harburg (1898-1981) Abstract A raga is a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood endorsed through performance. By a vadi swar is meant that note which plays the most significant role in expressing the raga. A samvadi swar similarly is the second most significant note. However, the determination of their significance has an element of subjectivity and hence we are motivated to find some truths through an objective analysis. The paper proposes a probabilistic method of note detection and demonstrates how the relative frequency (relative number of occurrences of the pitch) of the more important notes stabilize far more quickly than that of others. In addition, a count for distinct transitory and similar looking non-transitory (fundamental) frequency movements (but possibly embedding distinct emotions!) between the notes is also taken depicting the varnalankars or musical ornaments decorating the notes and note sequences as rendered by the artist. -

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

Sl.No Reg No First Party 2Nd Party Type of Deed Address Value Stamp

Peshi Report in Period From 01-04-2013 To 30-04-2013 Sl.No Reg First Party 2nd Party Type of Deed Address Value Stamp Book No Paid No. 4709 Unison Hotels Ltd. M/s Lockheed martin LEASE , LEASE WITH Vasant Kunj , House No. Unit No-2-4-6 and 8 1346973 485020 1 through its India Pvt Ltd through its SECURITY UPTO 10 ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 representative Mr. Representative Promila YEARS 4000, Area2 0, Area3 0 Vasant Kunj Rajesh Rustagi Pinto 4642 Dr. K C Goswami Sandeep Munjal LEASE , LEASE WITH Vasant Kunj , House No. 8161 ,Road No. , 25000 6100 1 SECURITY UPTO 5 Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 1100, Area2 YEARS 0, Area3 0 Vasant Kunj 5266 Ram Sarup Sohan Lal RELINQUISHMENT Sadh Nagar(Palam Colony) , House No. E-48 0 100 1 DEED , ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 0, RELINQUISHMENT Area2 0, Area3 0 Sadh Nagar(Palam DEED Colony) 4282 Nishant Sharma Mamta SALE , SALE WITHIN Vishwas Park , House No. Plot No-9 ,Road No. , 3160000 126400 1 MC AREA Mustail No. Ward No-147 South Mcd, Khasra 105/2, Area1 67, Area2 0, Area3 0 Vishwas Park 5123 Seema Devi Renu Tokas SALE , SALE WITHIN Munirka Village , House No. 359-B ,Road No. , 2770000 110800 1 MC AREA Mustail No. , Khasra 742, Area1 42, Area2 0, Area3 0 Munirka Village 5276 Saroj Sunil Kumar and Sandhya SALE , SALE WITHIN Sagarpur , House No. RZ-H/41 ,Road No. , 2500000 125000 1 Singh MC AREA Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 63, Area2 0, Area3 0 Sagarpur 5378 M K Sethi through Pratibha Advani SALE , SALE WITHIN Vasant Vihar , House No. -

(Dr) Utpal K Banerjee

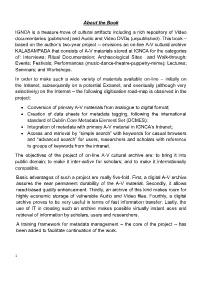

About the Book IGNCA is a treasure-trove of cultural artifacts including a rich repository of Video documentaries (published) and Audio and Video DVDs (unpublished). This book – based on the author’s two-year project -- envisions an on-line A-V cultural archive KALASAMPADA that consists of A-V materials stored at IGNCA for the categories of: Interviews; Ritual Documentation; Archaeological Sites and Walk-through; Events; Festivals; Performances (music-dance-theatre-puppetry-mime); Lectures; Seminars; and Workshops. In order to make such a wide variety of materials available on-line – initially on the Intranet, subsequently on a potential Extranet, and eventually (although very selectively) on the Internet – the following digitisation road-map is observed in the project: Conversion of primary A-V materials from analogue to digital format; Creation of data sheets for metadata tagging, following the international standard of Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES); Integration of metadata with primary A-V material in IGNCA’s Intranet; Access and retrieval by “simple search” with keywords for casual browsers and “advanced search” for users, researchers and scholars with reference to groups of keywords from the intranet. The objectives of the project of on-line A-V cultural archive are: to bring it into public domain; to make it inter-active for scholars; and to make it internationally compatible. Basic advantages of such a project are really five-fold. First, a digital A-V archive assures the near permanent durability of the A-V material. Secondly, it allows need-based quality enhancement. Thirdly, an archive of this kind makes room for highly economic storage of vulnerable Audio and Video files. -

Indian Traditional Grade 5

Foreword Welcome to the Musicea Arts and Culture Council Musicea Arts and Culture Council is a non-profit educational institution incorporated as a Section 8 Company of the Indian Companies Act, 2013. The primary objective of incorporation is to prepare curriculum, offer examinations, create career and jobs, recognise, award and honour achievements and promote young candidates in the field of music, dance, theatre, language, arts and sports. Musicea Arts and Culture Council is a college of national and international educators sharing the common dream of creating a world-class institution based in India to meet the requirements, demands and provide solutions to students and teachers. Musicea Arts and Culture Council have been formed to deliver an international standard grade-based music education system along with designing the national framework of music education in India. Several innovative and path-breaking measures implemented by the college council make it inclusive, holistic, and apt for 21st-century music education. The pioneering measures have already transformed the lives of thousands of educators and students and it is playing an active role in building a strong nation by assisting millions of aspiring students and teachers. Several initiatives are in place to protect, serve, and empower the teachers and students including a pension reward benefit. Musicea Arts and Culture Council have set benchmarks in creating international standard curriculum, offering examination, and performance, and by providing support, service, empowerment, inclusivity, decentralisation, growth, opportunity, career, finance, earnings, livelihood, award, reward and honour to thousands of teachers and students. Member teachers and students receive a series of direct benefits, honour and advantages from the Musicea Arts and Culture Council. -

Inde Du Nord1

Cité de la musique 1 L’Inde du Nord Traditions hindoustanies programme Jeudi 20, vendredi 21, samedi 22 et dimanche 23 mars 2003 Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours maximum avant chaque concert : www.cite-musique.fr La découverte des Indes « fabuleuses » des XVIe et XVIIe siècles frappa durablement l’imaginaire collectif occidental. Depuis, maintes fois décrite comme une terre de diversité, de contrastes et de paradoxes aux richesses infinies, l’Inde n’a cessé de fasciner. Sa culture musicale, fortement imprégnée d’une ancestrale pensée religieuse, a su préserver un héritage prestigieux tout en s’enrichissant régulièrement d’apports exogènes. La musique jouée au XIIIe siècle à la cour du Sultan de Delhi était alors essentiellement importée d’Asie centrale. Par un lent processus d’intégration et d’assimilation 2 réciproques, des générations de musiciens iraniens, turcs et hindous développèrent une culture musicale syncrétique, issue des mondes persan et indien. C’est ce formidable métissage qui permit aux instruments, aux formes et aux répertoires de s’enrichir mutuellement, en donnant corps à une culture hindoustanie qui allait devenir en Occident, dans le courant du XXe siècle, l’ambassadrice des « musiques du monde ». ’Inde du Nord - Traditions hindoustanies Traditions - ’Inde du Nord L Jeudi 20 mars - 20h Salle des concerts Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia, flûte bansuri Subhankar Banerjee, tabla Bhawani Shankar, pakhavaj Rupak Kulkarni, flûte bansuri 3 programme jeudi 20 mars - 20h Durée du concert : 2h Avec le soutien de l’Ambassade de France en Inde et de l’Indian Council for Cultural Relations Hariprasad Chaurasia Né en 1939, Hariprasad Chaurasia aurait dû, en bonne logique, reprendre le métier de son père, qui était lutteur. -

A Nonlinear Study on Time Evolution in Gharana

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC Archi Banerjee1,2*, Shankha Sanyal1,2*, Ranjan Sengupta2 and Dipak Ghosh2 1 Department of Physics, Jadavpur University 2 Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 India *[email protected] * Corresponding author Archi Banerjee: [email protected] Shankha Sanyal: [email protected]* Ranjan Sengupta: [email protected] Dipak Ghosh: [email protected] © 2019 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 15 April 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201904.0157.v1 A NONLINEAR STUDY ON TIME EVOLUTION IN GHARANA TRADITION OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC ABSTRACT Indian classical music is entirely based on the “Raga” structures. In Indian classical music, a “Gharana” or school refers to the adherence of a group of musicians to a particular musical style of performing a raga. The objective of this work was to find out if any characteristic acoustic cues exist which discriminates a particular gharana from the other. Another intriguing fact is if the artists of the same gharana keep their singing style unchanged over generations or evolution of music takes place like everything else in nature. In this work, we chose to study the similarities and differences in singing style of some artists from at least four consecutive generations representing four different gharanas using robust non-linear methods. For this, alap parts of a particular raga sung by all the artists were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA and MFDXA) technique. -

Bestguru.Comcarnatic Music ‐ Vocal 1978 Maharajapuram V

Name of the Artist Name of the Art / Field Awarded in Amba Sanyal (Costume Designing) Allied Theatre Arts 2008 Anant Gopal Shinde (Make‐up) Allied Theatre Arts 2003 Ashok Sagar Bhagat (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2002 Ashok Srivastava (Make‐up) Allied Theatre Arts 1981 D. G. Godse (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1988 Dolly Ahluwalia (Costume Design) Allied Theatre Arts 2001 G.N. Dasgupta (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1989 Gautam Bhattacharya (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2006 Goverdhan Panchal (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1985 H. V. Sharma (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 2005 Kajal Ghosh (Theatre Music) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Kamal Arora (Make‐up) Allied Theatre Arts 2009 Kamal Jain (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2011 Kamal Tewari (Theatre Music) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Kanishka Sen (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1994 Khaled Choudhury (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1986 Kuldeep Singh (Music for Theatre) Allied Theatre Arts 2009 M. S. Sathyu (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 1993 Mahendra Kumar (Scenic Design) Allied Theatre Arts 2007 Mansukh Joshi (Scenic & Light Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1997 N. Krishnamoorthy (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 1995 Nissar Allana (Stagecraft) Allied Theatre Arts 2002 R. K. Dhingra (Lighting) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 R. Paramashivan (Theatre Music) Allied Theatre Arts 2005 Robin Das (Scenic Design) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Roshen Alkazi (Costume Design) Allied Theatre Arts 1990 Shakti Sen (Make‐up) ‐ Allied Theatre Arts 2000 Sreenivas G. Kappanna (Lighting & Stage Design) Allied Theatre Arts 2003 Suresh Bhardwaj (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 2005 Tapas Sen (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1974 V. Ramamurthy (Lighting) Allied Theatre Arts 1977 Alathur S. Srinivasa Iyer Carnatic Music ‐ Vocal 1968 Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar Carnatic Music ‐ Vocal 1952 B.