A Nonlinear Study on Time Evolution in Gharana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

1 Syllabus for MA (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental

Syllabus for M.A. (Previous) Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental (Sitar, Sarod, Guitar, Violin, Santoor) SEMESTER-I Core Course – 1 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Historical and Theoretical Study of Ragas 70 Marks A. Historical Study of the following Ragas from the period of Sangeet Ratnakar onwards to modern times i) Gaul/Gaud iv) Kanhada ii) Bhairav v) Malhar iii) Bilawal vi) Todi B. Development of Raga Classification system in Ancient, Medieval and Modern times. C. Study of the following Ragangas in the modern context:- Sarang, Malhar, Kanhada, Bhairav, Bilawal, Kalyan, Todi. D. Detailed and comparative study of the Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 2 Theory Credit - 4 Theory : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Music of the Asian Continent 70 Marks A. Study of the Music of the following - China, Arabia, Persia, South East Asia, with special reference to: i) Origin, development and historical background of Music ii) Musical scales iii) Important Musical Instruments B. A comparative study of the music systems mentioned above with Indian Music. Internal Assessment 30 marks Core Course – 3 Practical Credit - 8 Practical : 70 Internal Assessment : 30 Maximum Marks : 100 Stage Performance 70 marks Performance of half an hour’s duration before an audience in Ragas selected from the list of Ragas prescribed in Appendix – I Candidate may plan his/her performance in the following manner:- Classical Vocal Music i) Khyal - Bada & chota Khyal with elaborations for Vocal Music. Tarana is optional. Classical Instrumental Music ii) Alap, Jor, Jhala, Masitkhani and Razakhani Gat with eleaborations Semi Classical Music iii) A short piece of classical music /Thumri / Bhajan/ Dhun /a gat in a tala other than teentaal may also be presented. -

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Categorization of Stringed Instruments with Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis

CATEGORIZATION OF STRINGED INSTRUMENTS WITH MULTIFRACTAL DETRENDED FLUCTUATION ANALYSIS Archi Banerjee*, Shankha Sanyal, Tarit Guhathakurata, Ranjan Sengupta and Dipak Ghosh Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Jadavpur University, Kolkata: 700032 *[email protected] * Corresponding Author ABSTRACT Categorization is crucial for content description in archiving of music signals. On many occasions, human brain fails to classify the instruments properly just by listening to their sounds which is evident from the human response data collected during our experiment. Some previous attempts to categorize several musical instruments using various linear analysis methods required a number of parameters to be determined. In this work, we attempted to categorize a number of string instruments according to their mode of playing using latest-state-of-the-art robust non-linear methods. For this, 30 second sound signals of 26 different string instruments from all over the world were analyzed with the help of non linear multifractal analysis (MFDFA) technique. The spectral width obtained from the MFDFA method gives an estimate of the complexity of the signal. From the variation of spectral width, we observed distinct clustering among the string instruments according to their mode of playing. Also there is an indication that similarity in the structural configuration of the instruments is playing a major role in the clustering of their spectral width. The observations and implications are discussed in detail. Keywords: String Instruments, Categorization, Fractal Analysis, MFDFA, Spectral Width INTRODUCTION Classification is one of the processes involved in audio content description. Audio signals can be classified according to miscellaneous criteria viz. speech, music, sound effects (or noises). -

Hindustani Percussion Syllabus Levels

Level 1 IndianRaga Hindustani Percussion Curriculum Practical Sample Question Set 1. Basic strokes: individual & combination 1. Play the basic 2. Basic phrases: at the discretion of the teacher phrases with Suggested: Thirakita, thirakitathaka, some variations – thirakitathaka tha gegethita, 3. Phrases with variations: at the discretion of the thirakitathaka etc teacher as advised by Suggested: Gege thita gege nana, dhadha thita teacher dhadha thina 2. Play teental theka Dha dha thirakita dha dha thina etc. in 3 speeds and 4. Teental basic pattern (Theka) in 3 speeds recite with beat 5. Basic Qaida, Rhela based patterns : at the 3. Play a small qaida discretion of the teacher 4. Tell us about the different parts of the tabla and Theory Requirements what they are 1. Building blocks of tala and counting made of 2. Recitation of all the above practical requirements Evaluation Adherence to Laya (proper tempo, rhythm), Posture, precision of strokes as well as proper recitation. Level 2 IndianRaga Hindustani Percussion Curriculum Practical & Theory Requirements Sample Questions set 1. Tala dadra, roopak, jhaptaal – recite and play in 1. Play thekas of 3 speeds Dadra, roopak 2. 3 finger tirkit (& more complex thirkit phrases) and Teental in 3 3. Further development of basic phrases from speeds level 1 2. Play some thirkit 4. 2 qaidas with 3 variations each – thi ta, thirakita based phrases based and more at the discretion of teacher 3. Play a qaida based 5. 3 thihais and 2 simple tukdas in Teental in thi ta with some variations 4. Play some thihais Evaluation in Teental Adherence to Laya (proper tempo, rhythm), Posture, 5. -

Analyzing the Melodic Structure of a Raga-Based Song

Georgian Electronic Scientific Journal: Musicology and Cultural Science 2009 | No.2(4) A Statistical Analysis Of A Raga-Based Song Soubhik Chakraborty1*, Ripunjai Kumar Shukla2, Kolla Krishnapriya3, Loveleen4, Shivee Chauhan5, Mona Kumari6, Sandeep Singh Solanki7 1, 2Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 3-7Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India * email: [email protected] Abstract The origins of Indian classical music lie in the cultural and spiritual values of India and go back to the Vedic Age. The art of music was, and still is, regarded as both holy and heavenly giving not only aesthetic pleasure but also inducing a joyful religious discipline. Emotion and devotion are the essential characteristics of Indian music from the aesthetic side. From the technical perspective, we talk about melody and rhythm. A raga, the nucleus of Indian classical music, may be defined as a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood conveyed by performance.. The strength of raga-based songs, although they generally do not quite maintain the raga correctly, in promoting Indian classical music among laymen cannot be thrown away. The present paper analyzes an old and popular playback song based on the raga Bhairavi using a statistical approach, thereby extending our previous work from pure classical music to a semi-classical paradigm. The analysis consists of forming melody groups of notes and measuring the significance of these groups and segments, analysis of lengths of melody groups, comparing melody groups over similarity etc. Finally, the paper raises the question “What % of a raga is contained in a song?” as an open research problem demanding an in-depth statistical investigation. -

A Novel EEG Based Study with Hindustani Classical Music

Can Musical Emotion Be Quantified With Neural Jitter Or Shimmer? A Novel EEG Based Study With Hindustani Classical Music Sayan Nag, Sayan Biswas, Sourya Sengupta Shankha Sanyal, Archi Banerjee, Ranjan Department of Electrical Engineering Sengupta,Dipak Ghosh Jadavpur University Sir C.V. Raman Centre for Physics and Music Kolkata, India Jadavpur University Kolkata, India Abstract—The term jitter and shimmer has long been used in In India, music (geet) has been a subject of aesthetic and the domain of speech and acoustic signal analysis as a parameter intellectual discourse since the times of Vedas (samaveda). for speaker identification and other prosodic features. In this Rasa was examined critically as an essential part of the theory study, we look forward to use the same parameters in neural domain to identify and categorize emotional cues in different of art by Bharata in Natya Sastra, (200 century BC). The rasa musical clips. For this, we chose two ragas of Hindustani music is considered as a state of enhanced emotional perception which are conventionally known to portray contrast emotions produced by the presence of musical energy. It is perceived as and EEG study was conducted on 5 participants who were made a sentiment, which could be described as an aesthetic to listen to 3 min clip of these two ragas with sufficient resting experience. Although unique, one can distinguish several period in between. The neural jitter and shimmer components flavors according to the emotion that colors it [11]. Several were evaluated for each experimental condition. The results reveal interesting information regarding domain specific arousal emotional flavors are listed, namely erotic love (sringara), of human brain in response to musical stimuli and also regarding pathetic (karuna), devotional (bhakti), comic (hasya), horrific trait characteristics of an individual. -

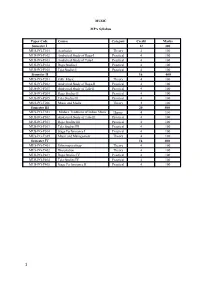

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks

MUSIC MPA Syllabus Paper Code Course Category Credit Marks Semester I 12 300 MUS-PG-T101 Aesthetics Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P102 Analytical Study of Raga-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P103 Analytical Study of Tala-I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P104 Raga Studies I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P105 Tala Studies I Practical 4 100 Semester II 16 400 MUS-PG-T201 Folk Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P202 Analytical Study of Raga-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P203 Analytical Study of Tala-II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P204 Raga Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P205 Tala Studies II Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T206 Music and Media Theory 4 100 Semester III 20 500 MUS-PG-T301 Modern Traditions of Indian Music Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P302 Analytical Study of Tala-III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Raga Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P303 Tala Studies III Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P304 Stage Performance I Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-T305 Music and Management Theory 4 100 Semester IV 16 400 MUS-PG-T401 Ethnomusicology Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-T402 Dissertation Theory 4 100 MUS-PG-P403 Raga Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P404 Tala Studies IV Practical 4 100 MUS-PG-P405 Stage Performance II Practical 4 100 1 Semester I MUS-PG-CT101:- Aesthetic Course Detail- The course will primarily provide an overview of music and allied issues like Aesthetics. The discussions will range from Rasa and its varieties [According to Bharat, Abhinavagupta, and others], thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore on music to aesthetics and general comparative. -

K-4 Curriculum Guide

India and its Music Classical North Indian music comes began thousands of years ago before the Christian Era in world history. Since this musical tradition is taught by an oral method (spoken or sung), instead of written, there were not reliable written records of the music except in very ancient books called the Vedas. These were books that recorded stories and hymns and prescriptions for how to behave according to the Hindu religion and were written 3,200 to 4,000 years ago. Some people believe they were written thousands of years earlier, and scholars debate this subject. India: Home to the World’s Great Religions In India many of the world’s great religions got their start. These would include Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and the Sikh religion. Also there are Indian Christians, and Islam is an important religion in the north of India. For many centuries Islamic culture had a big influence on music and mingled with the original music of India that existed before the Moslems conquered India. The result is a music that took elements of Islamic music from Persia, Turkey and Afghanistan and blended with the original music of India to become Hindustani music – the classical music of north India. The Hindu religion’s legends and mythology have many gods and goddesses, and these gods and goddesses are thought to be aspects of the One God Vishnu. Saraswati, Goddess of art, music, and learning One important goddess to Indian artists, scholars and musicians is Saraswati who is the goddess of art, music and learning. Mohandas K. -

Music from the Beginning

Review Article iMedPub Journals 2015 Insights in Blood Pressure http://journals.imedpub.com Vol. 1 No. 1:2 ISSN 2471-9897 Music and its Effect on Body, Brain/Mind: Archi Banerjee, Shankha A Study on Indian Perspective by Neuro- Sanyal, Ranjan Sengupta, Dipak Ghosh physical Approach Sir CV Raman Centre for Physics and Music, Jadavpur University, Kolkata Keywords: Music Cognition, Music Therapy, Diabetes, Blood Pressure, Neurocognitive Benefits Corresponding author: Archi Banerjee Received: Sep 20, 2015, Accepted: Sep 22, 2015, Submitted:Sep 29, 2015 [email protected] Music from the Beginning Sir CV Raman Centre for Physics and Music, The singing of the birds, the sounds of the endless waves of the Jadavpur University, Kolkata 700032. sea, the magical sounds of drops of rain falling on a tin roof, the murmur of trees, songs, the beautiful sounds produced by Tel: +919038569341 strumming the strings of musical instruments–these are all music. Some are produced by nature while others are produced by man. Natural sounds existed before human beings appeared Citation: Banerjee A, Sanyal S, Sengupta R, on earth. Was it music then or was it just mere sounds? Without et al. Music and its Effect on Body, Brain/ an appreciative mind, these sounds are meaningless. So music Mind: A Study on Indian Perspective by has meaning and music needs a mind to appreciate it. Neuro-physical Approach. Insights Blood Press 2015, 1:1. Music therefore may be defined as a form of auditory communication between the producer and the receiver. There are other forms of auditory communication, like speech, but the past and Raman, Kar followed by Rossing and Sundberg later on, difference is that music is more universal and evokes emotion. -

Rajeeb Chakraborty (Sarod) and Reena Shrivastava

The Asian Indian Classical Music Society 52318 N Tally Ho Drive, South Bend, IN 46635 Indian Classical Music Concert Dr. Rajeeb Chakarborty (sarod) Reena Chakraborty Shrivastava (sitar) with Subhen Chatterjee (tabla) September 6, 2009, Sunday, 7.30PM Dr. Rajeeb Chakraborty and Reena Chakraborty Shrivastava, are two of India’s leading classical instrumental musicians. They started training with their father, the eminent Sarod player, Pandit Robi Chakraborty, from the ages of six and five. They belong to the famous Maihar Gharana (school or tradition of music), following the tradition of the great masters Ustad Allauddin Khan, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Pandit Ravi Shankar. Both Rajeeb and Reena began performing publicly when they were nine years of age. As soloists, and sometimes together, they have participated in all the major music festivals in India, performed extensively in India, the US, Canada, and Western Europe, and have several musical recordings to their names. Subhen Chatterjee has accompanied most of India’s classical musicians. For more information, see http://www.rajeebchakraborty.com/ and http://www.aimusic.co.uk/artiste.html, and for a preview of their music, see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q57Oh3Ddnk8 Place: the Hesburgh Center for International and Peace Studies Auditorium, University of Notre Dame Tickets available at gate. General Admission: $10, AICMS Members and ND/SMC faculty: $5, Students: FREE Please also note that the AICMS had its annual general-body meeting on June 19, 2009. The new members of the Executive Committee were elected at the meeting. They are: Samir Bose (President), Vidula Agtey (Vice President), Amitava Dutt (Secretary), Ganesh Vaidyanathan (Treasurer) and Umesh Garg (Member-at-Large and Program Coordinator). -

Shruti Sangeet Academy

Shruti Sangeet Academy https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/ We provide Hindustani Classical,Semi Classical,Light Compositions,Sanskrit Shlokas and Compositions etc. About Us The Shruti Sangeet Academy is blessed to have a very motivated, sincere and dedicated group of students. Current Students are enrolled at one of three levels; Beginers, Intermediate and Advanced, based on their experience and comfort with the art form. Students follow a curriculum based on that offered by the Gandharva Mahavidhalaya . Gandharva Mahavidyalaya is an institution established in 1939 to popularize Indian classical music and dance. The Mahavidyalaya (school) came into being to perpetuate the memory of Pandit Vishnu Digamber Paluskar, the great reviver of Hindustani classical music, and to keep up the ideals set down by him. The first Gandharva Mahavidyala was established by him on 5 May 1901 at Lahore. The institution was relocated to Mumbai after 1947 and has subsequently established its administrative office at Miraj, Sangli District, Maharashtra. Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, New Delhi was established in 1939 by Padma Shri Pt. Vinaychandra Maudgalaya, from the Gwalior gharana, today it is the oldest music school in Delhi and is headed by noted Hindustani classical singer, Madhup Mudgal. At the Shruti Sangeet Academy, students up on completion of their curriculum successfully, have the option of applying and testing for the following certifications; (1) Sangeet Praveshika, equivalent to matriculation (generally a... For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/aboutus.html F a c t s h e e t Nature of Business :Service Provider CONTACT US Shruti Sangeet Academy Contact Person: Manager A1-602 Parsvnath Exotica Sector 53 Gurgaon - 122001, Haryana, India https://www.indiamart.com/shruti-sangeet-academy/.