The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Chairman, NEET UG Medical & Dental Admission

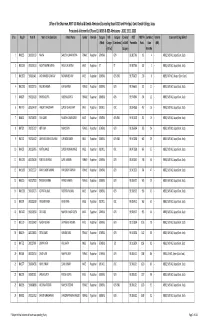

Office of the Chairman, NEET UG Medical & Dental Admission/Counseling Board-2020 and Principal, Govt. Dental College, Jaipur Provisional allotment list ( Round 1) MBBS & BDS Admissions - 2020, 19.11.2020 S.No. Reg.ID Neet ID Name of the Candidate Father's Name Gender Domicile Category Addl. Category Consider NEET NEET AI Combined Remarks Course and College alloted (Filled) Categor (Considered) ed Addl. Percentile Rank State (NRI) y (Filled) Category Merit No. 1 RM5055 3902001129 NAVYA SANJEEV KUMAR MIDHA FEMALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN 99.9857346 161 4 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 2 RM10225 3903203114 MOHIT KUMAR MEENA ARJUN LAL MEENA MALE Rajasthan ST ST 99.9857346 182 5 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 3 RM12673 3906001461 MOHAMMED AZAM KAIF MOHAMMED ARIF MALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN-EWS 99.9766633 236 8 - MBBS, RNT MC, Udaipur (Govt. Seat) 4 RM12152 3903203716 ARUSHI SHARMA AJAY SHARMA FEMALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN 99.9766633 301 11 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 5 RM8278 3903116183 SHREYA GUPTA MEGHRAJ GUPTA FEMALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN 99.9748344 334 12 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 6 RM7410 3903204143 HARSHIT CHAUDHARY SURESH CHAUDHARY MALE Rajasthan OBC NCL OBC 99.9649583 457 16 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 7 RM8612 3905108535 ISHU GARG MUKESH KUMAR GARG MALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN-EWS 99.9613005 501 19 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 8 RM7322 3905115207 KRITI JAIN MANOJ JAIN FEMALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN 99.9565454 565 24 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. Seat) 9 RM1741 3903326102 ABHISHEK SINGH CHAUHAN SURENDRA SINGH MALE Rajasthan GENERAL GEN-EWS 99.9478398 662 29 - MBBS, SMS MC, Jaipur (Govt. -

Nationalmerit-2020.Pdf

Rehabilitation Council of India ‐ National Board of Examination in Rehabilitation (NBER) National Merit list of candidates in Alphabatic Order for admission to Diploma Level Course for the Academic Session 2020‐21 06‐Nov‐20 S.No Name Father Name Application No. Course Institute Institute Name Category % in Class Remark Code Code 12th 1 A REENA PATRA A BHIMASEN PATRA 200928134554 0549 AP034 Priyadarsini Service Organization, OBC 56.16 2 AABHA MAYANK PANDEY RAMESH KUMAR PANDEY 200922534999 0547 UP067 Yuva Viklang Evam Dristibadhitarth Kalyan Sewa General 75.4 Sansthan, 3 AABID KHAN HAKAM DEEN 200930321648 0547 HR015 MR DAV College of Education, OBC 74.6 4 AADIL KHAN INTZAR KHAN 200929292350 0527 UP038 CBSM, Rae Bareli Speech & Hearing Institute, General 57.8 5 AADITYA TRIPATHI SOM PRAKASH TRIPATHI 200921120721 0549 UP130 Suveera Institute for Rehabilitation and General 71 Disabilities 6 AAINA BANO SUMIN MOHAMMAD 200926010618 0550 RJ002 L.K. C. Shri Jagdamba Andh Vidyalaya Samiti OBC 93 ** 7 AAKANKSHA DEVI LAKHAN LAL 200927081668 0550 UP044 Rehabilitation Society of the Visually Impaired, OBC 75 8 AAKANKSHA MEENA RANBEER SINGH 200928250444 0547 UP119 Swaraj College of Education ST 74.6 9 AAKANKSHA SINGH NARENDRA BAHADUR SING 201020313742 0547 UP159 Prema Institute for Special Education, General 73.2 10 AAKANSHA GAUTAM TARACHAND GAUTAM 200925253674 0549 RJ058 Ganga Vision Teacher Training Institute General 93.2 ** 11 AAKANSHA SHARMA MAHENDRA KUMAR SHARM 200919333672 0549 CH002 Government Rehabilitation Institute for General 63.60% Intellectual -

IME Annual Report 2020-2021 Low Size

Supported by Annual Report 2020-2021 Only in the darkness can “ you see the stars. ― Martin Luther King “ Namaste We have collectively endured one of the defining experiences of our life and times. What started off as a pause in the hustle and bustle of daily life has now become a happening that will forever define the way we see the world. Many of us experienced loss – of loved ones, of time, of precious moments, and of a sense of normalcy. There were days when I questioned everything, and felt the meaninglessness of it all. At the same time, I realized that the future is built one day at a time, by the seemingly small actions we take each day; that, as Martin Luther King said, everything that is done in the world is done by hope. And so, we see ourselves looking back at a most strange year, but one that I am glad to report has been extremely productive for the Indian Music Experience Museum, in our mission to build community through music. The team at IME seamlessly adapted to the online world. We ensured the continuity of music education at the Learning Centre. We unveiled two new online exhibits through an important partnership with Google Art and Culture. Our work in preserving musical traditions achieved an important milestone through the creation of an online archive on the life and works of legendary violinist and composer, Mysore T. Chowdiah, in collaboration with the Shankar Mahadevan Academy. We presented a wide variety of talks, discussions, workshops, showcases, and exhibit walkthroughs online, growing our audience beyond the geographic limitations of in-person events. -

Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free Static GK E-Book

oliveboard FREE eBooks FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS & VOCALISTS For All Banking and Government Exams Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Current Affairs and General Awareness section is one of the most important and high scoring sections of any competitive exam like SBI PO, SSC-CGL, IBPS Clerk, IBPS SO, etc. Therefore, we regularly provide you with Free Static GK and Current Affairs related E-books for your preparation. In this section, questions related to Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists have been asked. Hence it becomes very important for all the candidates to be aware about all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. In all the Bank and Government exams, every mark counts and even 1 mark can be the difference between success and failure. Therefore, to help you get these important marks we have created a Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. The list of all the Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists is given in the following pages of this Free E-book on Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Sample Questions - Q. Ustad Allah Rakha played which of the following Musical Instrument? (a) Sitar (b) Sarod (c) Surbahar (d) Tabla Answer: Option D – Tabla Q. L. Subramaniam is famous for playing _________. (a) Saxophone (b) Violin (c) Mridangam (d) Flute Answer: Option B – Violin Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists Free static GK e-book Famous Indian Classical Musicians and Vocalists. Name Instrument Music Style Hindustani -

Godrej Consumer Products Limited

GODREJ CONSUMER PRODUCTS LIMITED List of shareholders in respect of whom dividend for the last seven consective years remains unpaid/unclaimed The Unclaimed Dividend amounts below for each shareholder is the sum of all Unclaimed Dividends for the period Nov 2009 to May 2016 of the respective shareholder. The equity shares held by each shareholder is as on Nov 11, 2016 Sr.No Folio Name of the Shareholder Address Number of Equity Total Dividend Amount shares due for remaining unclaimed (Rs.) transfer to IEPF 1 0024910 ROOP KISHORE SHAKERVA I R CONSTRUCTION CO LTD P O BOX # 3766 DAMMAM SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 2 0025470 JANAKIRAMA RAMAMURTHY KASSEMDARWISHFAKROO & SONS PO BOX 3898 DOHA QATAR 240 8,160.00 3 0025472 NARESH KUMAR MAHAJAN 176 HIGHLAND MEADOW CIRCLE COPPELL TEXAS U S A 240 8,160.00 4 0025645 KAPUR CHAND GUPTA C/O PT SOUTH PAC IFIC VISCOSE PB 11 PURWAKARTA WEST JAWA INDONESIA 360 12,240.00 5 0025925 JAGDISHCHANDRA SHUKLA C/O GEN ELECTRONICS & TDG CO PO BOX 4092 RUWI SULTANATE OF OMAN 240 8,160.00 6 0027324 HARISH KUMAR ARORA 24 STONEMOUNT TRAIL BRAMPTON ONTARIO CANADA L6R OR1 360 12,240.00 7 0028652 SANJAY VARNE SSB TOYOTA DIVI PO BOX 6168 RUWI AUDIT DEPT MUSCAT S OF OMAN 60 2,040.00 8 0028930 MOHAMMED HUSSAIN P A LEBANESE DAIRY COMPANY POST BOX NO 1079 AJMAN U A E 120 4,080.00 9 K006217 K C SAMUEL P O BOX 1956 AL JUBAIL 31951 KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 10 0001965 NIRMAL KUMAR JAIN DEP OF REVENUE [INCOMETAX] OFFICE OF THE TAX RECOVERY OFFICER 4 15/295A VAIBHAV 120 4,080.00 BHAWAN CIVIL LINES KANPUR 11 0005572 PRAVEEN -

Education of Children with Special Needs 3.3

3.3 POSITION PAPER NATIONAL FOCUS GROUP ON EDUCATION OF CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS 3.3 POSITION PAPER NATIONAL FOCUS GROUP ON EDUCATION OF CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS ISBN 81-7450-494-X First Edition February 2006 Phalguna 1927 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or trans- PD 170T BB mitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. © National Council of Educational This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, re- Research and Training, 2006 sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher’s consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page, Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. OFFICES OF THE PUBLICATION DEPARTMENT, NCERT NCERT Campus Sri Aurobindo Marg New Delhi 110 016 108, 100 Feet Road Hosdakere Halli Extension Banashankari III Stage Bangalore 560 085 Navjivan Trust Building P.O.Navjivan Ahmedabad 380 014 CWC Campus Rs. 100.00 Opp. Dhankal Bus Stop Panihati Kolkata 700 114 CWC Complex Maligaon Guwahati 781 021 Publication Team Head, Publication : P. Rajakumar Department Chief Production : Shiv Kumar Officer Chief Editor : Shveta Uppal Chief Business : Gautam Ganguly Manager Printed on 80 GSM paper with NCERT watermark Editor : Benoy Banerjee Published at the Publication Department Production Assistant : Mukesh Gaur by the Secretary, National Council of Educational Research and Training, Cover and Layout Sri Aurobindo Marg, New Delhi 110 016 Shweta Rao and printed at Deekay Printers, 5/16, Kirti Nagar Indl. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Und Audiovisuellen Archive As

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives Internationale Vereinigung der Schall- und audiovisuellen Archive Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelles (I,_ '._ • e e_ • D iasa journal • Journal of the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives IASA • Organie de I' Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelle IASA • Zeitschchrift der Internationalen Vereinigung der Schall- und Audiovisuellen Archive IASA Editor: Chris Clark,The British Library National Sound Archive, 96 Euston Road, London NW I 2DB, UK. Fax 44 (0)20 7412 7413, e-mail [email protected] The IASA Journal is published twice a year and is sent to all members of IASA. Applications for membership of IASA should be sent to the Secretary General (see list of officers below). The annual dues are 25GBP for individual members and IOOGBP for institutional members. Back copies of the IASA Journal from 1971 are available on application. Subscriptions to the current year's issues of the IASA Journal are also available to non-members at a cost of 35GBP I 57Euros. Le IASA Journal est publie deux fois I'an etdistribue a tous les membres. Veuillez envoyer vos demandes d'adhesion au secretaire dont vous trouverez I'adresse ci-dessous. Les cotisations annuelles sont en ce moment de 25GBP pour les membres individuels et 100GBP pour les membres institutionels. Les numeros precedentes (a partir de 1971) du IASA Journal sont disponibles sur demande. Ceux qui ne sont pas membres de I'Association peuvent obtenir un abonnement du IASA Journal pour I'annee courante au coOt de 35GBP I 57 Euro. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

The West Bengal College Service Commission State

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION STATE ELIGIBILITY TEST Subject: MUSIC Code No.: 28 SYLLABUS Hindustani (Vocal, Instrumental & Musicology), Karnataka, Percussion and Rabindra Sangeet Note:- Unit-I, II, III & IV are common to all in music Unit-V to X are subject specific in music Unit-I Technical Terms: Sangeet, Nada: ahata & anahata , Shruti & its five jaties, Seven Vedic Swaras, Seven Swaras used in Gandharva, Suddha & Vikrit Swara, Vadi- Samvadi, Anuvadi-Vivadi, Saptak, Aroha, Avaroha, Pakad / vishesa sanchara, Purvanga, Uttaranga, Audava, Shadava, Sampoorna, Varna, Alankara, Alapa, Tana, Gamaka, Alpatva-Bahutva, Graha, Ansha, Nyasa, Apanyas, Avirbhav,Tirobhava, Geeta; Gandharva, Gana, Marga Sangeeta, Deshi Sangeeta, Kutapa, Vrinda, Vaggeyakara Mela, Thata, Raga, Upanga ,Bhashanga ,Meend, Khatka, Murki, Soot, Gat, Jod, Jhala, Ghaseet, Baj, Harmony and Melody, Tala, laya and different layakari, common talas in Hindustani music, Sapta Talas and 35 Talas, Taladasa pranas, Yati, Theka, Matra, Vibhag, Tali, Khali, Quida, Peshkar, Uthaan, Gat, Paran, Rela, Tihai, Chakradar, Laggi, Ladi, Marga-Deshi Tala, Avartana, Sama, Vishama, Atita, Anagata, Dasvidha Gamakas, Panchdasa Gamakas ,Katapayadi scheme, Names of 12 Chakras, Twelve Swarasthanas, Niraval, Sangati, Mudra, Shadangas , Alapana, Tanam, Kaku, Akarmatrik notations. Unit-II Folk Music Origin, evolution and classification of Indian folk song / music. Characteristics of folk music. Detailed study of folk music, folk instruments and performers of various regions in India. Ragas and Talas used in folk music Folk fairs & festivals in India. Unit-III Rasa and Aesthetics: Rasa, Principles of Rasa according to Bharata and others. Rasa nishpatti and its application to Indian Classical Music. Bhava and Rasa Rasa in relation to swara, laya, tala, chhanda and lyrics. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr.