Education of Children with Special Needs 3.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalmerit-2020.Pdf

Rehabilitation Council of India ‐ National Board of Examination in Rehabilitation (NBER) National Merit list of candidates in Alphabatic Order for admission to Diploma Level Course for the Academic Session 2020‐21 06‐Nov‐20 S.No Name Father Name Application No. Course Institute Institute Name Category % in Class Remark Code Code 12th 1 A REENA PATRA A BHIMASEN PATRA 200928134554 0549 AP034 Priyadarsini Service Organization, OBC 56.16 2 AABHA MAYANK PANDEY RAMESH KUMAR PANDEY 200922534999 0547 UP067 Yuva Viklang Evam Dristibadhitarth Kalyan Sewa General 75.4 Sansthan, 3 AABID KHAN HAKAM DEEN 200930321648 0547 HR015 MR DAV College of Education, OBC 74.6 4 AADIL KHAN INTZAR KHAN 200929292350 0527 UP038 CBSM, Rae Bareli Speech & Hearing Institute, General 57.8 5 AADITYA TRIPATHI SOM PRAKASH TRIPATHI 200921120721 0549 UP130 Suveera Institute for Rehabilitation and General 71 Disabilities 6 AAINA BANO SUMIN MOHAMMAD 200926010618 0550 RJ002 L.K. C. Shri Jagdamba Andh Vidyalaya Samiti OBC 93 ** 7 AAKANKSHA DEVI LAKHAN LAL 200927081668 0550 UP044 Rehabilitation Society of the Visually Impaired, OBC 75 8 AAKANKSHA MEENA RANBEER SINGH 200928250444 0547 UP119 Swaraj College of Education ST 74.6 9 AAKANKSHA SINGH NARENDRA BAHADUR SING 201020313742 0547 UP159 Prema Institute for Special Education, General 73.2 10 AAKANSHA GAUTAM TARACHAND GAUTAM 200925253674 0549 RJ058 Ganga Vision Teacher Training Institute General 93.2 ** 11 AAKANSHA SHARMA MAHENDRA KUMAR SHARM 200919333672 0549 CH002 Government Rehabilitation Institute for General 63.60% Intellectual -

Godrej Consumer Products Limited

GODREJ CONSUMER PRODUCTS LIMITED List of shareholders in respect of whom dividend for the last seven consective years remains unpaid/unclaimed The Unclaimed Dividend amounts below for each shareholder is the sum of all Unclaimed Dividends for the period Nov 2009 to May 2016 of the respective shareholder. The equity shares held by each shareholder is as on Nov 11, 2016 Sr.No Folio Name of the Shareholder Address Number of Equity Total Dividend Amount shares due for remaining unclaimed (Rs.) transfer to IEPF 1 0024910 ROOP KISHORE SHAKERVA I R CONSTRUCTION CO LTD P O BOX # 3766 DAMMAM SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 2 0025470 JANAKIRAMA RAMAMURTHY KASSEMDARWISHFAKROO & SONS PO BOX 3898 DOHA QATAR 240 8,160.00 3 0025472 NARESH KUMAR MAHAJAN 176 HIGHLAND MEADOW CIRCLE COPPELL TEXAS U S A 240 8,160.00 4 0025645 KAPUR CHAND GUPTA C/O PT SOUTH PAC IFIC VISCOSE PB 11 PURWAKARTA WEST JAWA INDONESIA 360 12,240.00 5 0025925 JAGDISHCHANDRA SHUKLA C/O GEN ELECTRONICS & TDG CO PO BOX 4092 RUWI SULTANATE OF OMAN 240 8,160.00 6 0027324 HARISH KUMAR ARORA 24 STONEMOUNT TRAIL BRAMPTON ONTARIO CANADA L6R OR1 360 12,240.00 7 0028652 SANJAY VARNE SSB TOYOTA DIVI PO BOX 6168 RUWI AUDIT DEPT MUSCAT S OF OMAN 60 2,040.00 8 0028930 MOHAMMED HUSSAIN P A LEBANESE DAIRY COMPANY POST BOX NO 1079 AJMAN U A E 120 4,080.00 9 K006217 K C SAMUEL P O BOX 1956 AL JUBAIL 31951 KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA 180 6,120.00 10 0001965 NIRMAL KUMAR JAIN DEP OF REVENUE [INCOMETAX] OFFICE OF THE TAX RECOVERY OFFICER 4 15/295A VAIBHAV 120 4,080.00 BHAWAN CIVIL LINES KANPUR 11 0005572 PRAVEEN -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

The Sixth String of Vilayat Khan

Published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited in 2018 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Copyright © Namita Devidayal, 2018 Interior photographs courtesy the Khan family albums unless otherwise acknowledged ISBN: 9789387578906 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher. Dedicated to all music lovers Contents MAP The Players CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? CHAPTER ONE The Early Years CHAPTER TWO The Making of a Musician CHAPTER THREE The Frenemy CHAPTER FOUR A Rock Star Is Born CHAPTER FIVE The Music CHAPTER SIX Portrait of a Young Musician CHAPTER SEVEN Life in the Hills CHAPTER EIGHT The Foreign Circuit CHAPTER NINE Small Loves, Big Loves CHAPTER TEN Roses in Dehradun CHAPTER ELEVEN Bhairavi in America CHAPTER TWELVE Portrait of an Older Musician CHAPTER THIRTEEN Princeton Walk CHAPTER FOURTEEN Fading Out CHAPTER FIFTEEN Unstruck Sound Gratitude The Players This family chart is not complete. It includes only those who feature in the book. CHAPTER ZERO Who Is This Vilayat Khan? 1952, Delhi. It had been five years since Independence and India was still in the mood for celebration. -

Activity Report 2009 – 2010

Activity Report 2009 – 2010 L V Prasad Eye Institute Kallam Anji Reddy Campus L V Prasad Marg, Banjara Hills Hyderabad 500 034, India Tel: 91 40 3061 2345 Fax: 91 40 2354 8271 e-mail: [email protected] L V Prasad Eye Institute Patia, Bhubaneswar 751 024 Orissa, India Tel: 91 0674 3989 2020 Fax: 91 0674 3987 130 e-mail: [email protected] L V Prasad Eye Institute G M R Varalakshmi Campus Door No: 11-113/1 Hanumanthawaka Junction Visakhapatnam 530 040 Andhra Pradesh, India Tel: 91 0891 3989 2020 Fax: 91 0891 398 4444 L V Prasad Eye Institute e-mail: [email protected] Excellence • Equity • Effi ciency Art with vision, for vision Artist-in-residence Sisir Sahana in his workshop on A view of the Art Gallery on Level 6 at Hyderabad LVPEI’s Kallam Anji Reddy campus, Hyderabad creating campus, where several works by Mr Surya Prakash, one of his signature glass sculptures. Inset: A piece from our senior artist-in-residence are on display. his latest collection, entitled “The long climb”. Inset: The hand that wields the paintbrush! L V Prasad Eye Institute Committed to excellence and equity in eye care Activity Report April 2009 – March 2010 Collaborating Centre for Prevention of Blindness L V Prasad Eye Institute, a not-for-profi t charitable organization, is governed by two trusts: Hyderabad Eye Institute and Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation. Donations to Hyderabad Eye Research Foundation are 175% exempt under section 35 (i) (ii) and donations made to Hyderabad Eye Institute are 50% exempt under section 80G of the Income Tax Act. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

The 1969 Amsect Conference Will Be Held in the Detroit Statler Hilton

NEWSMEN: The 1969 AmSECT Conference will UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA be held in the Detroit Statler Hilton NEWS SERVICE-2o-JOHNSTON HALL Hotel. News media representatives are MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA 55455 invited to attend any of the lectures JULY 1, 1969 r and the awards banquet JUly 19. A press room will be staffed during business For further information, contact: hours. Advance copies of the program ROBERT LEE, 373-5830 can be obtained from the AmSECT Office, 287 E. Sixth St., St. PaUl, Minn., 55101. MEDICAL GROUP CONCERNED WITH MECHANICAL METHODS TO HOLD CONFERENCE IN DETROIT (FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE) The American Society of Extra-Corporal Technology (AmSECT) -- technicians, surgeons, and para-medical personnel concerned with heart-lung and kidney-dialysis machines __ will hold its seventh annual conference July 16-19 in Detroit, Mich. Some 800 technicians, physicians, nurses, administrators, and engineers will be dis- cussing organ transplantation and preservation, kidney dialysis, and cardio-pulmonary technology. AmSECT President James B. Wade, supervisor of the experimental surgery laboratories at the University of Minnesota, explained that clinical extra-corporal technology (mechianical means to stimulate and perpetuate the functions of the human body) is a recent benefit of medical science. Every day hundreds of chronically ill people with severe kidney problems rely on artificial kidney machines and skilled medical technologists to cleanse their blood allowing them to lead relatively normal productive lives. Oxygenation technology -- the use of a by-pass pump to perpetuate blood circulation during open heart surgery -- has been used successfully for more than 15 years. The system, it is anticipated, may be used for longer periods to give a malfunctioning heart two or three days' rest. -

2020-21 National Scholarship Result (PDF)

F. No.1 10'1 9/07/2018-Sch Government of lndia Ministry of Tribal Affairs (Scholarship Division) Jeevan Tara Building, New Delhi, Dated: 13th August, 2021 sUBJECT: List of selected candidates for the year 2020-21 under the scheme of ,,National Fellowship and scholarship for Higher Education for sT students" List of selected candidates for award of Fellowships/scholarships under the scheme of "National Fellowship and Scholarship for Higher Education for ST students" for the year 2020-21 is as under:- l. Fellowships- 750 Awardees ll. Scholarships- 1000 Students for Graduation courses & Post-Graduation courses 2. The merit list has been prepared with the approval of competent authority as per scheme guidelines based on the marks entered by the student at Fellowship Portal/NSP and documents verified by concerned lnstitutes/Ministry. 3. lt may please be noted that the award of Fellowship/Scholarship is liable to be cancelled in the following circumstances: - lf the selected student is found to be ineligible to receive the fellowship/scholarship at any point of time; . ln case of any kind of misconduct committed by the student; . Concealment of facts or wrong declaration of marks/any other document; lv. lf the candidates is found availing similar kind of financial assistance from any other source; U nsatisfactory academic progress. Encl: As above tr".}JDJ,'#r,.nnr Deputy Secretary to the Government of lndia Copy to: - DDG (NlC) - For uploading the merit list on the Ministry's website. Annexure-2 750 Provisionally selected students for National Fellowship-2020-21 Annexure-2: List of 750 provisionally selected ST Candidates under the National Fellowship - 2020-21 Sl No. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2007 VOLUME II.A / ASIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2007, Volume II: Asia and the Middle East The directory of development organizations, listing 51.500 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

VOLUME XXIII, NO. 4 October, 1977 the JOURNAL of PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION

VOLUME XXIII, NO. 4 October, 1977 THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION Vol. XXIII NO.4 October-December, 1977 CONTENTS PAGE 'EDITORIAL NOTE 541 ,ARTICLES President Neelam Sanjiva Reddy 543 The Committee on Petitions .. 547 -H.V. Kamath The House of Lords and th: European Parliament. 55I -Sir Peter Henderson -PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Foreign Parliamentary Delegations in India 558 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 560 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 568 PARLIAMENTARY AND CoNSTITIJTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 574 DOCUMENTS OP CoNSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST The Salary and Allowances of Leaders of Opposition in Parliament Act, 1977 595 :SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha . 600 Rajya Sabha . 608 State Legislatures 618 1300K REVIEWS S. N. Jain : Administrative Tribunals in India: Existing and Proposed . 620 -K. B. Asthana B. L. Tomlinson : The Indian N at"onal Congress and the Raj 622 -N.C. Parashar RECENT LITERATURE OP PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 627 PAGE, ApPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Second Session of the Sixth Lok Sabha 635- II. Statement showing the work transacted during the Hun- dred and Second Session of Rajya Sabha 640' III. Statement showing the activities of State Legislatures during the period April 1 to June 30, 1977 644- IV. Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period May I, 1977 to July 31, 1977 ~g V. Bills passed by the State Legislatures during the period April I to June 30, 1977 649' VI. Ordinances issued by the Central Government during the period May 1 to July 31, 1977 and by the State Governments during the period April 1 to June 30, 1977 652 . -

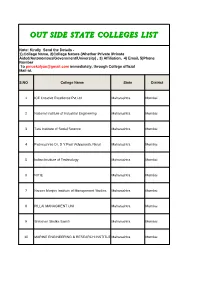

Out Side State Colleges List

OUT SIDE STATE COLLEGES LIST Note: Kindly Send the Details - 1).College Name, 2)College Nature (Whether Private /Private Aided/Autonomous/Government/University) , 3) Affiliation, 4) Email, 5)Phone Number To [email protected] immediately, through College official Mail-id. S.NO College Name State District 1 ICE Creative Excellence Pvt Ltd Maharashtra Mumbai 2 National Institute of Industrial Engineering Maharashtra Mumbai 3 Tata Institute of Social Science Maharashtra Mumbai 4 Padmashree Dr. D Y Patil Vidyapeeth, Nerul Maharashtra Mumbai 5 Indian Institute of Technology Maharashtra Mumbai 6 NITIE Maharashtra Mumbai 7 Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies Maharashtra Mumbai 8 PILLAI MANAGMENT UNI Maharashtra Mumbai 9 Shikshan Shulka Samiti Maharashtra Mumbai 10 MARINE ENGINEERING & RESEARCH INSTITUTEMaharashtra Mumbai 11 Institute of Hotel Management, Catering Technoloty Maharashtra& Applied Nutrition Mumbai 12 Central Institute for Research of Cotton TechnologyMaharashtra Mumbai 13 TATA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Maharashtra Mumbai 14 Grant Medical College Maharashtra Mumbai 15 College of Social Work Nirmala Niketan Maharashtra Mumbai 16 P.I.I.T,NEW PANVEL,NAVI MUMBAI. Maharashtra Mumbai 17 Ali Yavar Jung National Institute for the Hearing HandicappedMaharashtra Mumbai 18 Sir J.J. group of Hospitals Maharashtra Mumbai 19 St. Xavier s College Mumbai Maharashtra Mumbai 20 Sound Ideaz Academy Maharashtra Mumbai 21 King Edward Memorial Hospital Maharashtra Mumbai 22 Jamnalal Bajaj Institute Maharashtra Mumbai 23 Bombay Flying Club