Astronomical Distances

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identify the Following

1. This planet appears to be lying on its side. A. Jupiter B. Saturn C. Neptune D. Uranus E. none of these 2. This planet is the hottest on the solar system. This is due to the swirling clouds pf sulfur and sulfuric acid that obscure its surface making its atmosphere heavy and dense. A. Mercury B. Venus C. Earth D. Mars E. none of these 3. The only asteroid known to have a satellite. A. Ceres B. Eris C. Makemake D. Ida E. none of these 4. It is an anticyclonic storm on Jupiter that has been existing for 180 years and it is expected to last for another 345 years. A. GDS B. GBS C. GSS D. SSS E. none of these 5. It is the second largest planet and it has spectacular rings that can be seen on Earth by telescope. A. Jupiter B. Saturn C. Neptune D. Uranus E. none of these 6. It divides the planets into Inner Planets and Outer Planets. A. Kuiper Belt B. Asteroid Belt C. Oort Cloud D. heliopause E. none of these 7. Pluto is now considered a ____. A. Giant Planet B. Dwarf Planet C. Elf Planet D. Little Solar System E. none of these 8. It is made up of many small comets orbiting around the sun. It is the area wherein scientists believed Pluto to be a part of. A. Kuiper Belt B. Asteroid Belt C. Oort Cloud D. heliopause E. none of these 9. The belt in number 8 was discovered by ___. A. Nicolaus Copernicus B. -

Staff, Visiting Scientists and Graduate Students 2010

Staff, Visiting Scientists and Graduate Students at the Pescara Center November 2010 2 Contents ICRANet Faculty Staff……………………………………………………………………. p. 17 Adjunct Professors of the Faculty .……………………………………………………… p. 31 Lecturers……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 67 Research Scientists ……………………………………………………………………….. p. 93 Short-term Visiting Scientists …………………………………………………………... p. 109 Long-Term Visiting Scientists …………………………………………………………... p. 129 IRAP Ph. D. Students …………………………………………………………………….. p. 141 IRAP Ph. D. Erasmus Mundus Students………………………………………………. p. 161 Administrative and Secretarial Staff …………………………………………………… p. 171 3 4 ICRANet Faculty Staff Belinski Vladimir ICRANet Bianco Carlo Luciano ICRANet Novello Mario Cesare Lattes-ICRANet Chair CBPF, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Rueda Jorge A. ICRANet Ruffini Remo Università di Roma "Sapienza"and ICRANet Vereshchagin Gregory ICRANet Xue She-Sheng ICRANet 5 Adjunct Professors Of The Faculty Aharonian Felix Albert Benjamin Jegischewitsch Markarjan Chair Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, Dublin, Ireland Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysis, Heidelberg, Germany Amati Lorenzo Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica, Italy Arnett David Subramanyan Chandrasektar- ICRANet Chair University of Arizona, Tucson, USA Chakrabarti Sandip P. Centre for Space Physics, India Chardonnet Pascal Université de la Savoie, France Chechetkin Valeri Mstislav Vsevolodich Keldysh-ICRANet Chair Keldysh institute for Applied Mathematics Moscow, Russia Christodoulou Dimitrios ETH, Zurich, Switzerland Coppi Bruno -

Glossary of Terms Absorption Line a Dark Line at a Particular Wavelength Superimposed Upon a Bright, Continuous Spectrum

Glossary of terms absorption line A dark line at a particular wavelength superimposed upon a bright, continuous spectrum. Such a spectral line can be formed when electromag- netic radiation, while travelling on its way to an observer, meets a substance; if that substance can absorb energy at that particular wavelength then the observer sees an absorption line. Compare with emission line. accretion disk A disk of gas or dust orbiting a massive object such as a star, a stellar-mass black hole or an active galactic nucleus. An accretion disk plays an important role in the formation of a planetary system around a young star. An accretion disk around a supermassive black hole is thought to be the key mecha- nism powering an active galactic nucleus. active galactic nucleus (agn) A compact region at the center of a galaxy that emits vast amounts of electromagnetic radiation and fast-moving jets of particles; an agn can outshine the rest of the galaxy despite being hardly larger in volume than the Solar System. Various classes of agn exist, including quasars and Seyfert galaxies, but in each case the energy is believed to be generated as matter accretes onto a supermassive black hole. adaptive optics A technique used by large ground-based optical telescopes to remove the blurring affects caused by Earth’s atmosphere. Light from a guide star is used as a calibration source; a complicated system of software and hardware then deforms a small mirror to correct for atmospheric distortions. The mirror shape changes more quickly than the atmosphere itself fluctuates. -

HET Publication Report HET Board Meeting 3/4 December 2020 Zoom Land

HET Publication Report HET Board Meeting 3/4 December 2020 Zoom Land 1 Executive Summary • There are now 420 peer-reviewed HET publications – Fifteen papers published in 2019 – As of 27 November, nineteen published papers in 2020 • HET papers have 29363 citations – Average of 70, median of 39 citations per paper – H-number of 90 – 81 papers have ≥ 100 citations; 175 have ≥ 50 cites • Wide angle surveys account for 26% of papers and 35% of citations. • Synoptic (e.g., planet searches) and Target of Opportunity (e.g., supernovae and γ-ray bursts) programs have produced 47% of the papers and 47% of the citations, respectively. • Listing of the HET papers (with ADS links) is given at http://personal.psu.edu/dps7/hetpapers.html 2 HET Program Classification Code TypeofProgram Examples 1 ToO Supernovae,Gamma-rayBursts 2 Synoptic Exoplanets,EclipsingBinaries 3 OneorTwoObjects HaloofNGC821 4 Narrow-angle HDF,VirgoCluster 5 Wide-angle BlazarSurvey 6 HETTechnical HETQueue 7 HETDEXTheory DarkEnergywithBAO 8 Other HETOptics Programs also broken down into “Dark Time”, “Light Time”, and “Other”. 3 Peer-reviewed Publications • There are now 420 journal papers that either use HET data or (nine cases) use the HET as the motivation for the paper (e.g., technical papers, theoretical studies). • Except for 2005, approximately 22 HET papers were published each year since 2002 through the shutdown. A record 44 papers were published in 2012. • In 2020 a total of fifteen HET papers appeared; nineteen have been published to date in 2020. • Each HET partner has published at least 14 papers using HET data. • Nineteen papers have been published from NOAO time. -

EBL with GRB and Blazars Joel Primack with Rudy Gilmore, Alberto Dominguez, & Rachel Somerville

EBL with GRB and Blazars Joel Primack with Rudy Gilmore, Alberto Dominguez, & Rachel Somerville Thursday, March 25, 2010 The EBL is very difficult to observe directly because of foregrounds, especially the zodiacal light. Reliable lower limits are obtained by integrating the light from observed galaxies. The best upper limits come from (non-) attenuation of gamma rays from distant blazars, but these are uncertain because of the unknown emitted spectrum of these blazars. This talk concerns both the optical-IR EBL relevant to attenuation of TeV gamma rays, and also the UV EBL relevant to attenuation of gamma rays from very distant sources observed by Fermi and low-threshold ground- based ACTs. log dNγ/dE Just as IR light penetrates dust better than shorter wavelengths, so lower energy gamma rays penetrate the EBL better than higher energy, resulting in a softer observed gamma- ray spectrum from more distant sources. log E Thursday, March 25, 2010 PILLAR OF STAR BIRTH Carina Nebula in UV Visible Light Thursday, March 25, 2010 PILLAR OF STAR BIRTH Carina Nebula in IR Light Longer wavelength light penetrates the dust better Longer wavelength gamma rays also penetrate the EBL better Thursday, March 25, 2010 Gamma Ray Attenuation due to γγ e+e- If we know the intrinsic spectrum, we can infer the optical depth (E,z) from the observed spectrum. In -Γ practice, we assume that dN/dE|int is not harder than E with Γ = 1.5, since local sources have Γ ≥ 2. Thursday, March 25, 2010 Three approaches to calculate the EBL: Backward Evolution, which starts with the existing galaxy population and evolves it backward in time -- e.g., Stecker, Malkan, & Scully 2006. -

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland)

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland) American Astronomical Society August, 2019 100 — New Discoveries scope (JWST), as well as other large ground-based and space-based telescopes coming online in the next 100.01 — Review of TESS’s First Year Survey and two decades. Future Plans The status of the TESS mission as it completes its first year of survey operations in July 2019 will bere- George Ricker1 viewed. The opportunities enabled by TESS’s unique 1 Kavli Institute, MIT (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States) lunar-resonant orbit for an extended mission lasting more than a decade will also be presented. Successfully launched in April 2018, NASA’s Tran- siting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is well on its way to discovering thousands of exoplanets in orbit 100.02 — The Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Sur- around the brightest stars in the sky. During its ini- vey: Giant Planet and Brown Dwarf Demographics tial two-year survey mission, TESS will monitor more from 10-100 AU than 200,000 bright stars in the solar neighborhood at Eric Nielsen1; Robert De Rosa1; Bruce Macintosh1; a two minute cadence for drops in brightness caused Jason Wang2; Jean-Baptiste Ruffio1; Eugene Chiang3; by planetary transits. This first-ever spaceborne all- Mark Marley4; Didier Saumon5; Dmitry Savransky6; sky transit survey is identifying planets ranging in Daniel Fabrycky7; Quinn Konopacky8; Jennifer size from Earth-sized to gas giants, orbiting a wide Patience9; Vanessa Bailey10 variety of host stars, from cool M dwarfs to hot O/B 1 KIPAC, Stanford University (Stanford, California, United States) giants. 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology TESS stars are typically 30–100 times brighter than (Pasadena, California, United States) those surveyed by the Kepler satellite; thus, TESS 3 Astronomy, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, Califor- planets are proving far easier to characterize with nia, United States) follow-up observations than those from prior mis- 4 Astronomy, U.C. -

The 10 Parsec Sample in the Gaia Era?,?? C

A&A 650, A201 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140985 & c C. Reylé et al. 2021 Astrophysics The 10 parsec sample in the Gaia era?,?? C. Reylé1 , K. Jardine2 , P. Fouqué3 , J. A. Caballero4 , R. L. Smart5 , and A. Sozzetti5 1 Institut UTINAM, CNRS UMR6213, Univ. Bourgogne Franche-Comté, OSU THETA Franche-Comté-Bourgogne, Observatoire de Besançon, BP 1615, 25010 Besançon Cedex, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Radagast Solutions, Simon Vestdijkpad 24, 2321 WD Leiden, The Netherlands 3 IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, 14 av. E. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 4 Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino bajo del castillo s/n, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 5 INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Via Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy Received 2 April 2021 / Accepted 23 April 2021 ABSTRACT Context. The nearest stars provide a fundamental constraint for our understanding of stellar physics and the Galaxy. The nearby sample serves as an anchor where all objects can be seen and understood with precise data. This work is triggered by the most recent data release of the astrometric space mission Gaia and uses its unprecedented high precision parallax measurements to review the census of objects within 10 pc. Aims. The first aim of this work was to compile all stars and brown dwarfs within 10 pc observable by Gaia and compare it with the Gaia Catalogue of Nearby Stars as a quality assurance test. We complement the list to get a full 10 pc census, including bright stars, brown dwarfs, and exoplanets. -

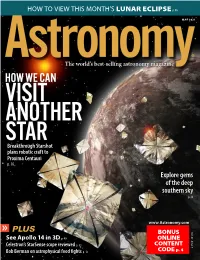

Breakthrough Starshot Plans Robotic Craft to Proxima Centauri P

HOW TO VIEW THIS MONTH’S LUNAR ECLIPSE p. 46 MAY 2021 The world’s best-selling astronomy magazine Breakthrough Starshot plans robotic craft to Proxima Centauri p. 16 Explore gems of the deep southern sky p. 48 www.Astronomy.com PLUS V BONUS o l . 4 9 p. 40 ONLINE • See Apollo 14 in 3D I s s u CONTENT e p. 54 Celestron’s StarSense scope reviewed 5 CODE p. 4 Bob Berman on astrophysical food fights p. 13 Breakthrough A voyage to the stars Using laser-propelled lightsails, tiny spacecraft could venture to the Sun’s nearest neighbor in just a few decades. BY JAKE PARKS n Nov. 6, 2018, as millions of telescope at Haleakalā Observatory in Americans cast their votes in a Hawaii. But it wasn’t until he began explor- hotly contested midterm elec- ing what he himself describes in his book tion, astrophysicist Avi Loeb as “an exotic hypothesis, without question” sat in his office surrounded that he began to take it seriously — if only Oby four television crews. Loeb, as a thought experiment. chair of Harvard University’s Department He drew his ‘Oumuamua hypothesis of Astronomy and author of the new from what was fresh in his mind. At that book Extraterrestrial (Houghton Mifflin point, Loeb had spent the previous few years Harcourt, 2021), was not being targeted working with some of the world’s brightest for his political insight. and most ambitious people quiry “A tantalizing, probing in fe.” he possibilities of alien li into t views Instead, the media atten- — Kirkus Re to develop an audacious e tion was due to his recent x interstellar mission that t eye-catching paper r would use lightsails to a t exploring whether the e venture to a nearby star. -

SPACETIME SINGULARITIES: the STORY of BLACK HOLES

1 SPACETIME SINGULARITIES: The STORY of BLACK HOLES We have already seen that the Big Bang is a kind of 'singularity' in the structure of spacetime. To the question "what was before the Big Bang?", one can reply, at least in the context of GR, that the question actually has no meaning - that time has no meaning 'before' the Big Bang. The point is that the universe can be ¯nite in extent in both time and space, and yet have no boundary in either. We saw what a curved space which is ¯nite in size but has no boundary means for a 2-d surface - a balloon is an example. Notice that if we made a balloon that curved smoothly except at one point (we could, for example, pinch it at this point) we could say that the balloon surface curvature was singular (ie., in¯nite) at this point. The idea of a 4-d spacetime with no boundary in spacetime, but with a ¯nite spacetime 4-dimensional volume, is a simple generalization of this. And just as it makes no sense, inside a 2-d balloon, to ask where the boundary is, we can have spacetime geometries which have no boundary in space or time, or where spacetime 'terminates' at a singularity. All of this is easy to say, but the attitude of most early workers in GR was to ignore the possible existence of singularities, and/or hope that they would just go away. The reaction of Einstein to the discovery of singular solutions to his equations was quite striking. -

Jeu Complet Recto

$* ) & !'! # 6 0 < ! 7* )) 4 4 $* & " * : * @ 1 * * 0* 4 ? * ) ) : 7 6 ! ! * 6! * ! *" ( 7 * ! # ! 0A * ) 8 0 ! $ ! ( ) ! & 8 B/CCD;EF/ GDC/<F6H;/C # & # ) 6 ID;5D;7 ! /*I * ; 8 4<J9 ' * '! ! ' +,-."/ + # , * $ ! ! * * ! " ! " #!$!% & '#!$!%! 7** ! # $ ! - % ! * ' !'.; ) &&$ ' ' 4 ! 5 & ' ' :)) * ( '' * 7 < #% ' ' * #) * + = ,- ) . 0 ! 4 < / ) ) $ * 8 3> $ 0* 01##'2 '- 0. 3'2 0 ) 1 )' -$ . % '45' -! . '5' -! '2 ' 0 . ) * ! !" '2)' 0 0 6 * $ * ! * 7 $ '45' * 0 )) * ! / * '5' ! ? ! * ! 1 ! / 0 * ! 0 8 * ) ! )) * #!% ! 9 * 6 * )) 1 ! ! # ) / * ) 0 * ! ) @ 0 9 ! 0 0 ! " )* 6 -

The Two-Component Jet of GRB 080413B⋆

A&A 526, A113 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201015320 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics The two-component jet of GRB 080413B R. Filgas1, T. Krühler1,2, J. Greiner1,A.Rau1, E. Palazzi3,S.Klose4, P. Schady1, A. Rossi4,P.M.J.Afonso1, L. A. Antonelli5,C.Clemens1,S.Covino6,P.D’Avanzo6, A. Küpcü Yolda¸s7,8,M.Nardini1, A. Nicuesa Guelbenzu4, F. Olivares1,E.A.C.Updike9,andA.Yolda¸s1,8 1 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstraße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Universe Cluster, Technische Universität München, Boltzmannstraße 2, 85748 Garching, Germany 3 INAF - IASF di Bologna, via Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy 4 Thüringer Landessternwarte Tautenburg, Sternwarte 5, 07778 Tautenburg, Germany 5 INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, via di Frascati 33, 00040 Monteporzio Catone (Roma), Italy 6 INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, via Bianchi 46, 23807 Merate, Italy 7 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 2, 85748 Garching, Germany 8 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, CB3 0HA Cambridge, UK 9 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634-0978, USA Received 1 July 2010 / Accepted 2 October 2010 ABSTRACT Aims. The quick and precise localization of GRBs by the Swift telescope allows the early evolution of the afterglow light curve to be captured by ground-based telescopes. With GROND measurements we can investigate the optical/near-infrared light curve of the afterglow of gamma-ray burst 080413B in the context of late rebrightening. Methods. Multi-wavelength follow-up observations were performed on the afterglow of GRB 080413B. -

Astronomy 2009 Index

Astronomy Magazine 2009 Index Subject Index 1RXS J160929.1-210524 (star), 1:24 4C 60.07 (galaxy pair), 2:24 6dFGS (Six Degree Field Galaxy Survey), 8:18 21-centimeter (neutral hydrogen) tomography, 12:10 93 Minerva (asteroid), 12:18 2008 TC3 (asteroid), 1:24 2009 FH (asteroid), 7:19 A Abell 21 (Medusa Nebula), 3:70 Abell 1656 (Coma galaxy cluster), 3:8–9, 6:16 Allen Telescope Array (ATA) radio telescope, 12:10 ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/sub-millimeter Array), 4:21, 9:19 Alpha (α) Canis Majoris (Sirius) (star), 2:68, 10:77 Alpha (α) Orionis (star). See Betelgeuse (Alpha [α] Orionis) (star) Alpha Centauri (star), 2:78 amateur astronomy, 10:18, 11:48–53, 12:19, 56 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) merging with Milky Way, 3:51 midpoint between Milky Way Galaxy and, 1:62–63 ultraviolet images of, 12:22 Antarctic Neumayer Station III, 6:19 Anthe (moon of Saturn), 1:21 Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), 4:24 APEX (Atacama Pathfinder Experiment) radio telescope, 3:19 Apollo missions, 8:19 AR11005 (sunspot group), 11:79 Arches Cluster, 10:22 Ares launch system, 1:37, 3:19, 9:19 Ariane 5 rocket, 4:21 Arianespace SA, 4:21 Armstrong, Neil A., 2:20 Arp 147 (galaxy pair), 2:20 Arp 194 (galaxy group), 8:21 art, cosmology-inspired, 5:10 ASPERA (Astroparticle European Research Area), 1:26 asteroids. See also names of specific asteroids binary, 1:32–33 close approach to Earth, 6:22, 7:19 collision with Jupiter, 11:20 collisions with Earth, 1:24 composition of, 10:55 discovery of, 5:21 effect of environment on surface of, 8:22 measuring distant, 6:23 moons orbiting,