Publisher's Note - Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of Cooperation in the Balkans Between Soe and Nkvd in January-August 1944

International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. XXVII No 1 2021 ASPECTS OF COOPERATION IN THE BALKANS BETWEEN SOE AND NKVD IN JANUARY-AUGUST 1944 Marian ZIDARU Black Sea House Association, Constanța, Romania [email protected] Abstract: A meeting was held on 14th January 1944 to discuss the possibilities which might exist for increased collaboration between S.O.E. and N.K.V.D. in the Balkans. The following agenda was submitted: A review of S.O.E. aims in each area and an outline of their resources with the object of examining the possibilities of a concerted Balkans plan for all countries concerned. The coordination of all these plans into one directive. The possibility of discussing such a plan with the N.K.V.D. in an endeavor to enlist their cooperation and assistance in a common plan for S.O.E., O.S.S. and N.K.V.D. Our article follows the evolution of these plans during January-August 1944. Keywords: SOE, NKVD, Balkan, O.S.S., Force 133 1. Introduction As regards Bulgaria: This was the one Cooperation in Eastern Europe countries country in regard to which there was some was difficult. No detailed study of SOE point in initiating discussions in Moscow operation here can be attempted. The for collaboration [1]. NKVD considered British plans regarding Hungary Poland, Czechoslovakia, 2. Yugoslavia Romania, and Bulgaria with deep concern. In Yugoslavia, there were two rival An SOE analyses report in 1944 concluded guerrilla groups within the resistance As regards Yugoslavia: The sending of a movement: a right-wing group called very strong Russian Mission to Tito will Chetniks led by Colonel Draza Mihajlovic bring to a head the questions of future co- and a group of communist partisans led by operation between the Russians and British Josip Broz Tito. -

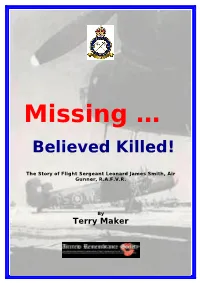

Missing … Believed Killed!

Missing … Believed Killed! The Story of Flight Sergeant Leonard James Smith, Air Gunner, R.A.F.V.R. By Terry Maker Missing - Believed Killed Terry Maker is a retired computer engineer, who has taken to amateur genealogy, after retirement due to ill health in 2003. He is the husband of Patricia Maker, nee Gash, and brother in law of Teddy Gash, (the cousins of Fl/Sgt L.J. Smith). He served as a Civilian Instructor in the Air Training Corps, at Stanford le Hope from 1988 until 1993.The couple live in Essex, and have done so for 36 years; they have no children, and have two golden retrievers. Disclaimer The contents of this document are subject to constant, and unannounced, revision. All of the foregoing is ‘as found’, and assumed to be correct at the time of compilation, and writing. However, this research is ongoing, and the content may be subject to change in the light of new disclosure and discovery, as new information comes to light. We ask for your indulgence, and understanding, in this difficult, and delicate area of research. There is copyright, on, and limited to, new material generated by the author, all content not by the author is, ‘as found’, in the Public Domain. © Terry Maker, 2009 Essex. Front Cover Watermark: “JP292-W undergoing routine maintenance at Brindisi, 1944” (Please note: This photograph is of unknown provenance, and is very similar to the “B-Beer, Brindisi, 1943” photo shown elsewhere in this booklet. It may be digitally altered, and could be suspect!) 2 A story of World War II Missing… Believed Killed By Terry Maker 3 To the men, living and dead, who did these things?” Paul Brickhill 4 Dedicated to the Memory of (Enhanced photograph) Flight Sergeant Leonard James Smith, Air Gunner, R.A.F.V.R. -

Air University Review: March-April 1977, Volume XXVIII, No. 3

The Professional Journal of the United States A ir Force the editors aerie Dr. Robert L. Pfaltzgraff, Jr., in our lead article, "Emerging Major Power Relationships," reflects on the shifting great power triangle of the United States, the Soviet Union, and the Peop!e's Republic of China. The cover, by Art Editor/lllustrator Bill DePaola, depicts an American eagle warily observing this triangle in a graphic elaboration of an abstract theme. For the first time in the experience of this editor, the Awards Committee members were unanimous in their first place votes for Major Don Alberts's "A Call from the Wilderness'' in the November-December 1976 issue. Aspiring authors who want to gain insight into subject matter that receives a very receptive reading by our editorial panei may want to re-examine that article. To the 50 percent of Air Force officers who necessarily receive an efficiency rating of three or below, it may be of more than passing interest to learn that the pseudonymous author of "I Am a Three" was recently promoted. You won't find Major Mark Wynn's name on the lieutenant colonel's promotion list, but we have it on good authority that the author who appeared under that nom de plume in the September-October 1976 issue is a living example that "threes" are promotable. Congratulations would seem to be appropriate, but how does one congratulate the anonymous? In this issue we find ourselves in the slightly embarrassed position of publishing an article by a member of the Air University Review Awards Committee. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 46

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 46 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2009 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore G R Pitchfork MBE BA FRAes *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain A J Byford MA MA RAF *Wing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS OPENING ADDRESS – Air Chf Mshl Sir David Cousins 7 THE NORTHERN MEDITERRANEAN 1943-1945 by Wg 9 Cdr Andrew Brookes AIRBORNE FORCES IN THE NORTH MEDITERRANEAN 20 THEATRE OF OPERATIONS by Wg Cdr Colin Cummings DID ALLIED AIR INTERDICTION -

The Allied Presence on Vis 1943-45 15 Jul 43 a C-47A

The Allied Presence on Vis 1943-45 15 Jul 43 A C-47A (ser. # 42-23515; Mission 9377) went MIA at Vis Island (apparently all crewmen were accounted for).1 Mid Aug 43 Some 3 weeks before Italy capitulated, the Partisans captured the entire Italian military garrison, of approx. 50 troops, on Vis without a fight, nor any casualties (variously described as an old fort and a lookout post atop Mt Hum). The Italians were disarmed and then freed, whereupon 10 hostages were taken from both Komiža and Vis, with the Italian demand that their weapons be returned within three days.2 31 Aug 43 With no weapons having been returned, the 20 hostages from Komiža and Vis were publicly executed by Italian firing squad.3 8 Sep 43 Italy capitulated. 24 Sep 43 Split evacuated by Partisans under Gen Koca Popović, to advancing Germans, having only controlled the city for eleven days.4 12 Oct 43 OSS began a 3-month mission, under Major Louis Huot, USA, to provide 6,000 tons of supplies to the Partisan garrison on Vis, via Bari, aboard the HMS Gull (Sub-Lt Taylor, RNR) and the little coal steamer SS Bakar. Huot wrote of his main interlocutors being the garrison commander, Commander Sergije Makiedo (actually the Commissar, Lt Col [later Admiral] Josip Černi/Černy was the Cdr), and Jože Poduje. They would moor in the "Baie des Anglais," a little basin on the eastern side of Vis harbor. A derelict convent on the waterfront then served as the Partisan hospital, with 3 young indefatigable doctors, “Bobin,” who spoke shaky French, “Zucalo” who spoke appalling English, & “Biacic” who spoke basic German [note how Strutton cites only 2 Partisan doctors on Vis, the charlatan, “Dr. -

Miszelle Die Royal Air Force Über Osterreich. Kriegs

Miszelle Wolfgang Etschmann Die Royal Air Force über Osterreich. Kriegs- und Friedensoperationen der britischen Luftwaffe während des Zweiten Weltkrieges und im beginnenden Kalten Krieg, 1940-1947 Die historische Aufarbeitung der »Besatzungszeit« in Österreich zwischen 1945 und 1955 hatte bisher vor allem die amerikanischen und sowjetischen Verwal- tungsbehörden und Besatzungstruppen zum Thema. Intensivere und genauere Forschungen über das britische Besatzungselement lassen sich hingegen erst in den späten siebziger Jahren finden. Die Geschichte der britischen Streitkräfte, die in den ersten beiden Jahren nach 1945 als Besatzungstruppen in Österreich stationiert waren, kann - soweit es sich um Heeresverbände handelt - mittlerweile als recht gut erforscht gelten. Speziell durch die Arbeiten Siegfried Beers, bzw. die von ihm in den letzten Jahren ange- regten und initiierten Untersuchungen sowie einzelne Veröffentlichungen von stei- rischen und Kärntner Historikern, die sich intensiver mit der Landesgeschichte nach 1945 beschäftigt haben, kann von einem guten Forschungsstand gesprochen werden1. Interessanterweise ist über die britische Royal Air Force (RAF) als Element der britischen Besatzung in Österreich wenig bekannt und im deutschsprachigen Raum bisher kaum etwas publiziert worden. Und dies, obwohl die Verbände der RAF in Österreich vom Kriegsende bis zum Jahresbeginn 1947 gemäß den britischen strategischen Überlegungen eine nicht unbedeutende Rolle im ab Ende April 1945 stetig eskalierenden politischen Kon- Die vorliegende Arbeit -

Researc Report

. ' . -~ ·: .. .. · · ~. ' ... ·• -~ -. • ' • - J'. ,Jjt-1 - · CtN-~ -fJ/rwf~- fo.i'#/2-2 :J ;. f~o''.£ - '\ ·I'·ll r" ~~ ~/If/~ --~ ~================~~~;:==~========== ~ Air War College ·~ .. --. r-'~========================= ~-~ • '.l AN ANALYSIS OF THE CIRCUMSTANCES SURROUNDING THE RESCUE AND EVACUATION OF ALLIED AIRCREWKEN FROM YUGOSL\VIA, 1941-1945 ?-::-:: <::.::: :.r · < - .. -- - RESEARC REPORT '.' Ne. 128 •1 Thomas T. Matteson ' ~ . AIR WAR COLLEGE c:: AIR UNIVERSITY UNITED STATES Alit . FO.. CE MAXWELL Alit F08.CE BASE, ALABAMA t----·- :- ·· ·-·· --· ___ ......,. ~:: f. >X,f. :f .-· . - JTl u; :..~ .- > .- -: - > ~ ~ n- ' ,' _.. AIR WAR COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY REPORT NO. 128 AN ANALYSIS OF THE CIRCUMSTANCES SURROUNDING THE RESCUE AND EVACUATION OF ALLIED AIRCREWMEN FR<»-1 YUGOSL.l VIA, 1941-194 5 by Thomas T. Matteson,..-••••~ Commander, USCG A RESEARCH REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA April 1977 DISCLAIMER-ABSTAINER This research report represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Air War College, the Department of the Air Force, the Commandant, or the United States Coast Guard. This document is the property of the United States Government and is not to be reproduced in whole or in part without the permission of the Commandant, Air ~r College, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. ii I AIR WAR COLLEGE RESEARCH REPORT SUMMARY No. 128 TITLE: An Analysis of the Circumstances Surrounding the Rescue and Evacuation of Allied Aircrewmen from Yugoslavia, 1941-1945 AUTHOR: Thomas T. Matteson, CaiiD<mder, USCG The establishment of the Air Force's first Air Crew Rescue Unit and its unparalled operations in occupied Yugoslavia are discussed in the light of Allied policy toward Yugoslav resistance groups. -

Fires of Resistance Army Air Forces Special Operations in the Balkans During World War II

The U. S Army Air Forces in World War II Fueling the Fires of Resistance Army Air Forces Special Operations in the Balkans during World War II William M. Leary DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited Air Force History and Museums Program 1995 "20050429 009 Fueling the Fires of Resistance Of all the Army Air Forces' many operations in the Second World War, none was more demand- ing or important than those supporting the activ- ity of resistance groups fighting the Axis powers. The special operations supporting the Yugoslav- ian partisans fighting the forces of Nazism in the Balkans required particular dedication and ex- pertise. Balkan flying conditions demanded the best of flying skills, and the tenacious German defenses in that troubled region complicated this challenge even further. In this study, Professor William Leary examines what might fairly be considered one of the most important early expe- riences in the history of Air Force special opera- tions. It is ironic that, fifty years after these activities, the Air Force today is heavily involved in Balkan operations, including night air drops of supplies. But this time, the supplies are for hu- manitarian relief, not war. The airlifters commit- ted to relieving misery in that part of the world follow in the wake of their predecessors who, fifty years ago, flew the night skies with courage and skill to help bring an end to Nazi tyranny. PAGE Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. -

Martin B-26 Marauder 60” Wing Span Plan

Martin B-26 Marauder 60” Wing Span Plan. Not to be confused with Douglas A-26 Invader. The Martin B-26 Marauder was a World War II twin-engine medium bomber built by the Glenn L. Martin Company. First used in the Pacific Theater in early 1942, it was also used in the Mediterranean Theater and in Western Europe. After entering service with the U.S. Army, the aircraft received the reputation of a "Widowmaker" due to the early models' high rate of accidents during takeoff and landings. The Marauder had to be flown by exact airspeeds, particularly on final approach and when one engine was out. The 150 mph (241 km/h) speed on short final was intimidating to pilots who were used to much slower speeds, and whenever they slowed down below what the manual stated, the aircraft would stall and crash.[3] The B-26 became a safer aircraft once crews were re-trained and after aerodynamics modifications (increase of wing span and incidence, to give better take off performance, and a larger fin and rudder).[4] After aerodynamic and design changes, the aircraft distinguished itself as "the chief bombardment weapon on the Western Front" according to a United States Army Air Forces dispatch from 1946.[citation needed] The Marauder ended World War II with the lowest loss rate of any USAAF bomber.[5] A total of 5,288 were produced between February 1941 and March 1945; 522 of these were flown by the Royal Air Force and the South African Air Force. By the time the United States Air Force was created as an independent service separate from the Army in 1947, all Martin B-26s had been retired from US service. -

Folder 14 Evacuation of Yugoslav Refugees, Folder 2

~; .· L::_-v t:Lc iA_"'-il ,.-., ~ Y"'b 0.5 l~v ~e_,J;.(J-" ~..r:. 0 (c}.,t..r 2...; :tJ - G) .r i :,_ . ~. D FFC-76 ( 11-42) CROSS REFERENCE ON ...........•.• - •.••....... FOR: Amendment to this License Extension of this License Renewal of this License . Correspondence concerning this application Other (Specify) For further correspondence wjth Ackermann concerning Yugoslav Refugees - SEE: ACKERMANN; LEOHARD E. -- US Polad, AFHQ, .Al'O 512, FM, N~w York October 6, 194:4. Dear John: I have just returned from Bari where I ~de a fa~rly thorough check-up on the proposed evacuation of Jewish refugees from Yugoslavia¥"' A.s I cabled y0u (No. 113) only 29 persons were evacuated on September 18th and none since that date. Since we had been given to understand that the people would be coming out at a rate faster than this, it was felt that some inves tigation was necessary. '!'he first thing learned was that the weather con ditions were bad. As you no doubt are already aware, these people are located in Croatia ~.nd can only come out by plane--usually .the return trip of th~ planes which bring in supplies. Starting about September 27th there has been bad flying weather all over Italy and Yugoslavia--so bad, in fact, that the 15th Air Force has been.grounded for the longest period in its entire existance. This, however, did not account for the per iod betwwen tb& 18th ~d the 27th. This might have been accounted ~or by the evacuation of airmen and wounded who have priority over refugees but an exam ination of records showed that very ~e• persons in these categories arrived during this.period. -

Josip Broz Tito Sabrana Djela

ODBOR ZA IZDAVANJE SABRANIH DJELA JOSIPA BROZA TITA Liubčo Arsov, predsjednik, [dr Vladimir Bakarić, Anka Berus, I Rodoljub čolakovic,! RadivojT)avidović, Stane Dolanc, Veselin Đuranović, Aslan Fazlija, Slavko Janevski, Lazar Koliševski, Nandor Major, Petar Matić, [Miha MarinkoJ dr Miroslav Pečujlić, dr Ivan Perić, dr Pavle Savić, Petar Štambolić, Lidija Šentjurc, Franc Šetinc, dr Mijat Šuković, dr Marko Šunjić, dr Arif Tanović, Fabijan Treo, Mihajlo Zvicer, Drago Vukša, sekretar Odbora JOSIP BROZ TITO - SABRANA DJELA REDAKCIJA ZA IZDAVANJE SABRANIH DJELA JOSIPA BROZA TITA David Atlagić, Ismail Bajra, dr Dušan Bilandžić, dr Drago Borovčanin, dr Milovan Bosić, Slobodan Bosiljčić, (dr Velimir Brezovski, dr Pero Damjanović, dr Tone Ferenc, ar Branislav (jTigorijević, zamjenik glavnog i odgovornog urednika, dr Danilo Kecić, dr Milan Matić, Veljko Miladinović, Pero Morača, dr Ivan Perić, dr Branko Petranović, dr Nikola Popović, zamjenik glavnog i odgovornog urednika, dr Miljan Radović, dr Stanislav Stojanović, Fabijan Trgo GLAVNI I ODGOVORNI UREDNIK dr Pero Damjanović SEKRETAR REDAKCIJE dr Enes Milak NAUČNA p r i p r e m a INSTITUT ZA SAVREMENU ISTORIJU BEOGRAD TOM 20 Istraživanja, napomene, hronologija i priprema za štampu DIMITRIJE BRAJUŠKOVIĆ JOSIP BROZ TITO SABRANA DJELA TOM DVADESETI 16. APRIL — 30. JUN 1944. IZDAVAČKI CENTAR »KOMUNIST«, BEOGRAD BEOGRADSKI IZDAVAČKO-GRAFIČKI ZAVOD, BEOGRAD IZDAVAČKO KNJIŽARSKO PODUZEČE »NAPRIJED«. ZAGREB BEOGRAD 1984. VIII juna stvorile i održale mostobran s preko 900(XX) svojih vojnika, čime su stvoreni uslovi za dalje uspješno savezničko nastupanje i na tom frontu. Na jugoslovenskom ratištu još nije postojala čvrsta linija fronta, ali su se po Titovim naređenjima, uputstvima i direktivama oformljavala sve izrazitija vojišta. U Sloveniji je 7. -

VAZDUŠNA BOMBARDOVANJA SARAJEVA U DRUGOM SVJETSKOM RATU Sead Vrana

UDK: 355.469.2 (497.6 Sarajevo) ”1941/1945” Review article DOI: 10.51237/issn.2774-1180.2020.19.275 VAZDUŠNA BOMBARDOVANJA SARAJEVA U DRUGOM SVJETSKOM RATU Sead Vrana Federalna uprava civilne zaštite [email protected] Apstrakt: Vazdušna bombardovanja Sarajeva tokom Drugog svjetskog rata pogodila su sve dijelove tadašnjeg gradskog područja. Većina žrtava bili su civili, a bombe su padale i na objekte bez vojne važnosti. Prve napade 1941. godine izvršilo je vazduhoplovstvo nacističke Njemačke, a od kraja 1943. godine bombardovanja su vršila saveznička vazduhoplovstva. Nad Sarajevom su dejstvovale i taktičke i strategijske snage bombama mase od 50 do 1800 kg. Poređenjem podataka iz dostupnih arhiva vazduhoplovnih jedinica koje su vršile bombardovanja, zatim vojnih i civilnih vlasti u Sarajevu, te ranijih istraživanja vazdušnog rata, ovaj članak prikazuje koliki ratni napor je uložen u bombardovanja, na koje ciljeve je bio usmjeren, koja gradska područja je pogodio, kojom svrhom i kakvim rezultatom. Također, stavlja bombardovanja u historijski kontekst, kako bi rasvijetlio razloge koji su doveli do razornih posljedica po grad i stanovnike. Ključne riječi: Drugi svjetski rat, Sarajevo, vazduhoplovstvo, vazdušna bombardovanja, Luftwaffe, USAAF, RAF Abstract: Aerial bombardment during World War Two hit every part of the Sarajevo city area. Most of the victims were civilians as bombs fell on the buildings and areas which had no military significance. First attacks were executed by the Nazi Germany Luftwaffe, while from the end of 1943, the