Micrographia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the Father of Microscope

Turkish Journal of Biochemistry – Türk Biyokimya Dergisi 2016; 41(1): 58–62 Education Sector Letter to the Editor – 93585 Emine Elif Vatanoğlu-Lutz*, Ahmet Doğan Ataman Medicine in philately: Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microscope Pullardaki tıp: Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, mikroskobun kaşifi DOI 10.1515/tjb-2016-0010 only one lens to look at blood, insects and many other Received September 16, 2015; accepted December 1, 2015 objects. He was first to describe cells and bacteria, seen through his very small microscopes with, for his time, The origin of the word microscope comes from two Greek extremely good lenses (Figure 1) [3]. words, “uikpos,” small and “okottew,” view. It has been After van Leeuwenhoek’s contribution,there were big known for over 2000 years that glass bends light. In the steps in the world of microscopes. Several technical inno- 2nd century BC, Claudius Ptolemy described a stick appear- vations made microscopes better and easier to handle, ing to bend in a pool of water, and accurately recorded the which led to microscopy becoming more and more popular angles to within half a degree. He then very accurately among scientists. An important discovery was that lenses calculated the refraction constant of water. During the combining two types of glass could reduce the chromatic 1st century,around year 100, glass had been invented and effect, with its disturbing halos resulting from differences the Romans were looking through the glass and testing in refraction of light (Figure 2) [4]. it. They experimented with different shapes of clear glass In 1830, Joseph Jackson Lister reduced the problem and one of their samples was thick in the middle and thin with spherical aberration by showing that several weak on the edges [1]. -

Why Natural History Matters

Why Practice Natural History? Why Natural History Matters Thomas L. Fleischner Thomas L. Fleischner ([email protected]) is a professor in the Environmental Studies Program at Prescott College, 220 Grove Avenue, Prescott, Arizona 86301 U.S.A., and founding President of the Natural History Network. The world needs natural history now more children: we turn over stones, we crouch to than ever. Because natural history – which look at insects crawling past, we turn our I have defined as “a practice of intentional heads to listen to new sounds. Indeed, as focused attentiveness and receptivity to the we grow older we have to learn to not pay more-than-human world, guided by attention to our world. The advertising honesty and accuracy” (Fleischner 2001, industry and mass consumer culture 2005) – makes us better, more complete collude to encourage this shrinking of the human beings. This process of “careful, scope of our attention. But natural history patient … sympathetic observation” attentiveness is inherent in us, and it can be (Norment 2008) – paying attention to the reawakened readily. larger than human world – allows us to build better human societies, ones that are It is easy to forget what an anomalous time less destructive and dysfunctional. Natural we now live in. Natural history is the history helps us see the world, and thus oldest continuous human tradition. ourselves, more accurately. Moreover, it Throughout human history and encourages and inspires better stewardship “prehistory,” attentiveness to nature was so of the Earth. completely entwined with daily life and survival that it was never considered as a Natural history encourages our conscious, practice separate from life itself. -

The Voc and Swedish Natural History. the Transmission of Scientific Knowledge in the Eighteenth Century

THE VOC AND SWEDISH NATURAL HISTORY. THE TRANSMISSION OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Christina Skott In the later part of the eighteenth century Sweden held a place as one of the foremost nations in the European world of science. This was mainly due to the fame of Carl Linnaeus (1707–78, in 1762 enno- bled von Linné), whose ground breaking new system for classifying the natural world created a uniform system of scientific nomenclature that would be adopted by scientists all over Europe by the end of the century. Linnaeus had first proposed his new method of classifying plants in the slim volume Systema Naturae, published in 1735, while he was working and studying in Holland. There, he could for the first time himself examine the flora of the Indies: living plants brought in and cultivated in Dutch gardens and greenhouses as well as exotic her- baria collected by employees of the VOC. After returning to his native Sweden in 1737 Linnaeus would not leave his native country again. But, throughout his lifetime, Systema Naturae would appear in numerous augmented editions, each one describing new East Indian plants and animals. The Linnean project of mapping the natural world was driven by a strong patriotic ethos, and Linneaus would rely heavily on Swed- ish scientists and amateur collectors employed by the Swedish East India Company; but the links to the Dutch were never severed, and he maintained extensive contacts with leading Dutch scientists through- out his life. Linnaeus’ Dutch connections meant that his own students would become associated with the VOC. -

200 Central Park West - American Museum of Natural History, Borough of Manhattan

June 15, 2021 Name of Landmark Building Type of Presentation Month xx, year Public Hearing The current proposal is: Preservation Department – Item 4, LPC-21-08864 200 Central Park West - American Museum of Natural History, Borough of Manhattan How to Testify Via Zoom: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84946202332?pwd=MjdJUjY2a0d3TWEwUDVlVEorM2lCQT09 Note: If you want to testify on an item, join the Webinar ID: 849 4620 2332 Zoom webinar at the agenda’s “Be Here by” Passcode: 951064 time (about an hour in advance). When the By Phone: Chair indicates it’s time to testify, “raise your 1 646-558-8656 US (New York) hand” via the Zoom app if you want to speak (*9 on the phone). Those who signed up in 877-853-5257 US (Toll free) advance will be called first. 888-475-4499 US (Toll free) Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt Proposed Relocation Theodore Roosevelt Park, MN NYC Parks American Museum of Natural History Site Location Manhattan American Museum of Natural History Frederick Douglass Circle Upper West Side 2 Site Location View of the American Museum of Natural History, 2020, NYC Parks 3 Site Location Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt, 2020, NYC Parks 4 Existing Site Views Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt looking northwest (left) and southwest (right) 2015, NYC Parks 5 History Roosevelt Memorial model, Date unknown, AMNH 6 History October 28, 1940, New York Times October 1940 view of the equestrian statue, from the south. Photo by Thane L. Bierwert, AMNH Research Library / Digital Special Collections 7 History Landmarks Preservation Commission designation photo of the Roosevelt Memorial, 1967, LPC 8 Composition and Context 9 Photo by Denis Finnin / AMNH Sustained Public Controversy Vandalism of Equestrian Statue of Vandalism of Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, 1971, New 2017, NYC Parks 10 York Times Sustained Public Controversy Addressing the Statue exhibition at AMNH, C. -

Dioscorides De Materia Medica Pdf

Dioscorides de materia medica pdf Continue Herbal written in Greek Discorides in the first century This article is about the book Dioscorides. For body medical knowledge, see Materia Medica. De materia medica Cover of an early printed version of De materia medica. Lyon, 1554AuthorPediaus Dioscorides Strange plants RomeSubjectMedicinal, DrugsPublication date50-70 (50-70)Pages5 volumesTextDe materia medica in Wikisource De materia medica (Latin name for Greek work Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, Peri hul's iatrik's, both means about medical material) is a pharmacopeia of medicinal plants and medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until it supplanted the revised herbs during the Renaissance, making it one of the longest of all natural history books. The paper describes many drugs that are known to be effective, including aconite, aloe, coloxinth, colocum, genban, opium and squirt. In all, about 600 plants are covered, along with some animals and minerals, and about 1000 medicines of them. De materia medica was distributed as illustrated manuscripts, copied by hand, in Greek, Latin and Arabic throughout the media period. From the sixteenth century, the text of the Dioscopide was translated into Italian, German, Spanish and French, and in 1655 into English. It formed the basis of herbs in these languages by such people as Leonhart Fuchs, Valery Cordus, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Klusius, John Gerard and William Turner. Gradually these herbs included more and more direct observations, complementing and eventually displacing the classic text. -

Conservation Update for Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Slide 1 Conservation Update Robert Hooke’s Micrographia London:1667 Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] Hello, my name is Eliza Gilligan and I am the Conservator for University Library Collections at the University of Virginia. This slide show is a “re-broadcast” of a presentation I made at a library staff “Town Meeting” on September 16, 2011. I hope my notes to the slides fill in the gaps left by the transition from live presentation to this show, but if you have a question, please feel free to email me <[email protected]>. I’d like to share a little bit of information about the process of conservation treatment and also a little bit of information about what a unique opportunity conservation treatment provides in terms of examining the components of a book, using my recent treatment of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia as an example. Conservation of this title and many volumes from our circulating collections were made possible by a generous gift from Kathy Duffy, friend of the University Library Slide 2 What is Micrographia? The landmark publication that initiated the field of microscopy. The first edition was published in London in 1665. Robert Hooke described his use of a microscope for direct observation, provided text of his findings but most importantly, large illustrations to demonstrate his findings. The UVa Library copy is from the second issue printed in 1667. Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] This book was brought to my attention by a faculty member of the Rare Book School who uses it every year in her History of Illustration class. -

Robert Hooke's Micrographia of 1665 and 1667

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2010; 40:374–6 Ex libris doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2010.420 © 2010 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Robert Hooke’s Micrographia of 1665 and 1667 Until recently Robert Hooke’s name more important than Hooke’s own was not widely known to the public. observations using microscopy. Later, When he was remembered it was Hooke himself learned Dutch so that usually in connection with memories, he could read Leeuwenhoek’s letters. often vague, of ‘Hooke’s Law’ (the extension of an elastic body is However, while Leeuwenhoek’s proportional to the force applied to descriptions of his findings were extend it). However, little or nothing lively and detailed, the sketches he was remembered of Hooke’s connec- provided were fairly crude. Hooke, tions with Robert Boyle, Christopher on the other hand, devised a method Wren and, later, Isaac Newton and of looking at a sheet of paper with others of that exalted circle, particularly one eye while observing through John Wilkins who probably introduced the microscope with the other so him into it, of his long service to the that he could trace the outlines of Royal Society’s regular programme of the virtual image seen by the demonstrations, of his contributions to microscope eye on the paper. He the theories of light and, indeed, of describes doing this to allow him to gravitation, of his surveying of London measure the magnification achieved after the Great Fire of 1666 and his ex libris RCPE by his instruments. He then worked overseeing of much of its reconstruction. -

Why Darwin Delayed, Or Interesting Problems and Models in the History of Science Robert J

WHY DARWIN DELAYED, OR INTERESTING PROBLEMS AND MODELS IN THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE ROBERT J. RICHARDS Though Darwin had forinulated his theory of evolution by natural selection by early fall of 1x37. he did not publish it until 1859 in the Origirr of Species. Darwin thus delayed publicly revealing his theory for some twenty years. Why did he wait so long'? Initially [hi\ may not seem an important or interesting question. but many historians have so regarded it. They have developed a variety of historiographically different ex- planations This essay considers these several explanations, though with a larger pur- pose in mind: to suggest what makes for interesting problems in history of science and what kinds of historiographic models will hest handle them In October of 1836, Charles Darwin returned from his five-year voyage on the Beagle. During his travel around the world, he appears not to have given serious thought to the possibility that species were mutable, that they slowly changed over time. But in the summer and spring of 1837, he began to reflect precisely on this possibility, as his journal indicates: "In July opened first notebook on 'Transformation of Species'-Had been greatly struck from about Month of previous March on character of S. American fossils--& species on Galapagos Archipelago. These facts [are the] origin (especially latter) of all my views."' Darwin's views on evolution really only began to congeal some six months after his voyage. In the summer of 1837, he started a series of notebooks in which he worked on the theory that species were transformed over generations. -

“The Natural History of My Inward Self”: Sensing Character in George Eliot’S Impressions of Theophrastus Such S

129.1 ] “The Natural History of My Inward Self”: Sensing Character in George Eliot’s Impressions of Theophrastus Such s. pearl brilmyer Attempts at description are stupid: who can all at once describe a human be- ing? Even when he is presented to us we only begin that knowledge of his ap- pearance which must be completed by innumerable impressions under differing circumstances. We recognize the alphabet; we are not sure of the language. —George Eliot, Daniel Deronda (160) ILL NOT A TINY spECK VERY CLOSE TO OUR VISION BLOT Out “ the glory of the world, and leave only a margin by Wwhich we see the blot?” asks the narrator of Middle- march (1874). Indeed it will, comes the answer, and in this regard there is “no speck so troublesome as self” (392). Metaphors of sen- sory failure in Eliot seem to capture the self- absorption of characters who discount empirical knowledge in favor of their own straitened worldviews. In Middlemarch Casaubon’s shortsightedness is tied to his egocentric attempts to “understand the higher inward life” (21). Dorothea, who marries Casaubon in an effort to attain this kind of understanding, is correspondingly “unable to see” the right con- clusion (29), can “never see what is quite plain” (34), “does not see things” (52), and is “no judge” of visual art, which is composed in “a language [she does] not understand” (73). When Eliot describes obstacles to sensation, however, she does more than provide a critique of egoism in which the corrective is sympathetic exchange. More basically, Eliot’s fascination with the S. -

Identifying Exotic Animals in Pliny's Natural History

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-15-2013 12:00 AM The Roman Ethnozoological Tradition: Identifying Exotic Animals in Pliny's Natural History Benjamin Moser The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Debra Nousek The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Classics A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Benjamin Moser 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Moser, Benjamin, "The Roman Ethnozoological Tradition: Identifying Exotic Animals in Pliny's Natural History" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1206. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1206 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROMAN ETHNOZOOLOGICAL TRADITION: IDENTIFYING EXOTIC ANIMALS IN PLINY’S NATURAL HISTORY (Thesis format: Monograph) by Benjamin Moser Graduate Program in Classical Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Benjamin Moser 2013 Abstract Only recently has Pliny’s Natural History garnered favourable reception, as scholarship has expanded from Quellenforschung and the comparisons to modern biological understanding to a more balanced approach. Continuing with this perspective, I seek to appreciate both the Natural History on its own merit, free of modern scientific scrutiny, and Pliny as a participating author in the work beyond the previously stigmatized compiler or unknown perspective. -

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

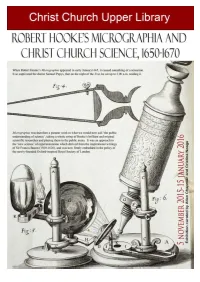

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

Milestones in Botany Botany Begins with Aristotle by Ruth A

Milestones in Botany Botany Begins with Aristotle By Ruth A. Sparrow Again this year Hobbies will give its readers glimpses of the rare first and early editions in the Milestones of Science Collection. Ruth A. Sparrow, Librarian, writes Milestones in Botany as the sixth in her series.—Editor's Note. • • • Living plants are found in all plants, many of them noted for their parts of the world in more or less pro- medicinal value. fusion. The mountain top and the Dioscorides (c. 50 A. D.), a con- desert each has its particular growth. temporary of Pliny, was a Greek bot- The science of this vegetation is bot- anist and physician in the Roman any. Plants from the smallest micro- army. He traveled extensively in this scopic plant to the largest tree have latter capacity and became intensely in- been of interest to man, for they pro- terested in botany. As a result of this vided him with food, shelter, medicine, combination of profession and hobby clothing, transportation, and other ne- he became the greatest of medical bot- cessities and comforts. All these were anists. He knew over six hundred material interests, and for centuries no plants which he has described in Ma- systematic study of plants was under- teria Medica (Venice, 1499). This taken. work holds an important place both in Aristotle (c. 350 B. C.) is credited the history of medicine and botany. as the first patron of botany and the As late as the seventeenth century no first so-called director of a botanic gar- drug was considered genuine that did den.