Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the Father of Microscope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Provisions Rescue Commercial Genetic Research After Association for Molecular Pathology, Et Al., V

Health Law and Policy Brief Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 5 10-16-2013 Do the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Provisions Rescue Commercial Genetic Research after Association for Molecular Pathology, et al., v. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, et al. Thomas J. Kniffen American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/hlp Part of the Health Law Commons Recommended Citation Kniffen, Thomas J. "Do the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Provisions Rescue Commercial Genetic Research after Association for Molecular Pathology, et al., v. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, et al." Health Law & Policy Brief 5, no. 2 (2011): 32-38. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Health Law and Policy Brief by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PPACA's provisions and its potential to rescue In 4ssociation for Molecular Pathology et al. commercial genetic research if the Federal v. US. Patent and lrademark Office, et al., the Circuit's decision in Association for Molecular U.S. District Court for the Southern District Pathology is reversed by the Supreme Court. of New York invalidated a claim to patent genetically developed material on the basis L, Patecints ad eneicResearch, that "[t]he patents issued by the [United States AU.S Constitution Patent Office] are directed to a law of nature and were therefore improperly granted."1 The Congress is authorized by the U.S. -

Role of the Microbiologist in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology J

7/7/2014 Role of the Microbiologist in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology J. Kristie Johnson, Ph.D. Director, Microbiology Laboratory University of Maryland Medical Center Associate Professor, Department of Pathology University of Maryland School of Medicine Disclosures 1 7/7/2014 Objectives Understand the importance of the microbiology laboratory to infection control, the hospital epidemiologist, and the infectious disease physician. Understand the various techniques available to assist in an epidemiological investigation. Infectious Disease Diagnostics Diagnostic tests for infectious diseases have changed to: Detection of infectious agents/molecules/genes replacing growth and identification procedures. Turn around time minutes to hours replacing days to weeks Evolved through transitional research. Direct impact patient care Need hospital based Microbiology is now studies to validate their clinical effectiveness. part of the healthcare team 2 7/7/2014 Infection Prevention Programs Role in infections Monitor Understanding the epidemiology of HAIs Determine rates of infections Surveillance Prevent Intervene to prevent infections Education Control Outbreak investigation The clinical microbiology laboratory is essential to a comprehensive infection prevention program Role of the Microbiology Laboratory in Infection Control Specimen Collection Accurate Identification and Susceptibility Testing Laboratory Information Systems Rapid Diagnostic Testing Reporting of Laboratory Data Outbreak Recognition and Investigations-Molecular -

8113-Yasham Neden Var-Nick Lane-Ebru Qilic-2015-318S.Pdf

KOÇ ÜNiVERSiTESi YAYINLARI: 87 BiYOLOJi Yaşam Neden Var? Nick Lane lngilizceden çeviren: Ebru Kılıç Yayına hazırlayan: Hülya Haripoğlu Düzelti: Elvan Özkaya iç rasarım: Kamuran Ok Kapak rasarımı: James Jones The Vital Question © Nick Lane, 2015 ©Koç Üniversiresi Yayınları, 2015 1. Baskı: lsranbul, Nisan 2016 Bu kitabın yazarı, eserin kendi orijinal yararımı olduğunu ve eserde dile getirilen rüm görüşlerin kendisine air olduğunu, bunlardan dolayı kendisinden başka kimsenin sorumlu rurulamayacağını; eserde üçüncü şahısların haklarını ihlal edebilecek kısımlar olmadığını kabul eder. Baskı: 12.marbaa Sertifika no: 33094 Naro Caddesi 14/1 Seyranrepe Kağırhane/lsranbul +90 212 284 0226 Koç Üniversiresi Yayınları lsriklal Caddesi No:181 Merkez Han Beyoğlu/lsranbul +90 212 393 6000 [email protected] • www.kocuniversirypress.com • www.kocuniversiresiyayinlari.com Koç Universiry Suna Kıraç Library Caraloging-in-Publicarion Dara Lane, Nick, 1967- Yaşam neden var?/ Nick Lane; lngilizceden çeviren Ebru Kılıç; yayına hazırlayan Hülya Haripoğlu. pages; cm. lncludes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-605-5250-94-2 ı. Life--Origin--Popular works. 2. Cells. 1. Kılıç, Ebru. il. Haripoğlu, Hülya. 111. Tirle. QH325.L3520 2016 Yaşam Neden Var? NICKLANE lngilizceden Çeviren: Ebru Kılıç ffi1KÜY İçindeki le� Resim Listesi 7 TEŞEKKÜR 11 GiRİŞ 17 Yaşam Neden Olduğu Gibidir? BiRİNCi BÖLÜM 31 Yaşam Nedir? Yaşamın ilk 2 Milyar Yılının Kısa Ta rihi 35 Genler ve Doğal Ortamla ilgili Sorun 39 Biyolojinin Kalbindeki Kara Delik 43 Karmaşıklık Yo lunda Kayıp Adımlar -

PROTISTS Shore and the Waves Are Large, Often the Largest of a Storm Event, and with a Long Period

(seas), and these waves can mobilize boulders. During this phase of the storm the rapid changes in current direction caused by these large, short-period waves generate high accelerative forces, and it is these forces that ultimately can move even large boulders. Traditionally, most rocky-intertidal ecological stud- ies have been conducted on rocky platforms where the substrate is composed of stable basement rock. Projec- tiles tend to be uncommon in these types of habitats, and damage from projectiles is usually light. Perhaps for this reason the role of projectiles in intertidal ecology has received little attention. Boulder-fi eld intertidal zones are as common as, if not more common than, rock plat- forms. In boulder fi elds, projectiles are abundant, and the evidence of damage due to projectiles is obvious. Here projectiles may be one of the most important defi ning physical forces in the habitat. SEE ALSO THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Geology, Coastal / Habitat Alteration / Hydrodynamic Forces / Wave Exposure FURTHER READING Carstens. T. 1968. Wave forces on boundaries and submerged bodies. Sarsia FIGURE 6 The intertidal zone on the north side of Cape Blanco, 34: 37–60. Oregon. The large, smooth boulders are made of serpentine, while Dayton, P. K. 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organi- the surrounding rock from which the intertidal platform is formed zation: the provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky is sandstone. The smooth boulders are from a source outside the intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 45: 137–159. intertidal zone and were carried into the intertidal zone by waves. Levin, S. A., and R. -

Protist Phylogeny and the High-Level Classification of Protozoa

Europ. J. Protistol. 39, 338–348 (2003) © Urban & Fischer Verlag http://www.urbanfischer.de/journals/ejp Protist phylogeny and the high-level classification of Protozoa Thomas Cavalier-Smith Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3PS, UK; E-mail: [email protected] Received 1 September 2003; 29 September 2003. Accepted: 29 September 2003 Protist large-scale phylogeny is briefly reviewed and a revised higher classification of the kingdom Pro- tozoa into 11 phyla presented. Complementary gene fusions reveal a fundamental bifurcation among eu- karyotes between two major clades: the ancestrally uniciliate (often unicentriolar) unikonts and the an- cestrally biciliate bikonts, which undergo ciliary transformation by converting a younger anterior cilium into a dissimilar older posterior cilium. Unikonts comprise the ancestrally unikont protozoan phylum Amoebozoa and the opisthokonts (kingdom Animalia, phylum Choanozoa, their sisters or ancestors; and kingdom Fungi). They share a derived triple-gene fusion, absent from bikonts. Bikonts contrastingly share a derived gene fusion between dihydrofolate reductase and thymidylate synthase and include plants and all other protists, comprising the protozoan infrakingdoms Rhizaria [phyla Cercozoa and Re- taria (Radiozoa, Foraminifera)] and Excavata (phyla Loukozoa, Metamonada, Euglenozoa, Percolozoa), plus the kingdom Plantae [Viridaeplantae, Rhodophyta (sisters); Glaucophyta], the chromalveolate clade, and the protozoan phylum Apusozoa (Thecomonadea, Diphylleida). Chromalveolates comprise kingdom Chromista (Cryptista, Heterokonta, Haptophyta) and the protozoan infrakingdom Alveolata [phyla Cilio- phora and Miozoa (= Protalveolata, Dinozoa, Apicomplexa)], which diverged from a common ancestor that enslaved a red alga and evolved novel plastid protein-targeting machinery via the host rough ER and the enslaved algal plasma membrane (periplastid membrane). -

Protists/Fungi Station Lab Information

Protists/Fungi Station Lab Information 1 Protists Information Background: Perhaps the most strikingly diverse group of organisms on Earth is that of the Protists, Found almost anywhere there is water – from puddles to sediments. Protists rely on water. Somea re marine (salt water), some are freshwater, some are terrestrial (land dwellers) in moist soil and some are parasites which live in the tissues of others. The Protist kingdom is made up of a wide variety of eukaryotic cells. All protist cells have nuclei and other characteristics eukaryotic features. Some protists have more than one nucleus and are called “multinucleated”. Cellular Organization: Protists show a variety in cellular organization: single celled (unicellular), groups of single cells living together in a close and permanent association (colonies or filaments) or many cells = multicellular organization (ex. Seaweed). Obtaining food: There is a variety in how protists get their food. Like plants, many protists are autotrophs, meaning they make their own food through photosynthesis and store it as starch. It is estimated that green protist cells chemically capture and process over a billion tons of carbon in the Earth’s oceans and freshwater ponds every year. Photosynthetic or “green” protists have a multitude of membrane-enclosed bags (chloroplasts) which contain the photosynthetic green pigment called chlorophyll. Many of these organisms’ cell walls are similar to that of plant cells and are made of cellulose. Others are “heterotrophs”. Like animals, they eat other organisms or, like fungi, receiving their nourishment from absorbing nutrient molecules from their surroundings or digest living things. Some are parasitic and feed off of a living host. -

Protistology an International Journal Vol

Protistology An International Journal Vol. 10, Number 2, 2016 ___________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC FORUM «PROTIST–2016» Yuri Mazei (Vice-Chairman) Welcome Address 2 Organizing Committee 3 Organizers and Sponsors 4 Abstracts 5 Author Index 94 Forum “PROTIST-2016” June 6–10, 2016 Moscow, Russia Website: http://onlinereg.ru/protist-2016 WELCOME ADDRESS Dear colleagues! Republic) entitled “Diplonemids – new kids on the block”. The third lecture will be given by Alexey The Forum “PROTIST–2016” aims at gathering Smirnov (Saint Petersburg State University, Russia): the researchers in all protistological fields, from “Phylogeny, diversity, and evolution of Amoebozoa: molecular biology to ecology, to stimulate cross- new findings and new problems”. Then Sandra disciplinary interactions and establish long-term Baldauf (Uppsala University, Sweden) will make a international scientific cooperation. The conference plenary presentation “The search for the eukaryote will cover a wide range of fundamental and applied root, now you see it now you don’t”, and the fifth topics in Protistology, with the major focus on plenary lecture “Protist-based methods for assessing evolution and phylogeny, taxonomy, systematics and marine water quality” will be made by Alan Warren DNA barcoding, genomics and molecular biology, (Natural History Museum, United Kingdom). cell biology, organismal biology, parasitology, diversity and biogeography, ecology of soil and There will be two symposia sponsored by ISoP: aquatic protists, bioindicators and palaeoecology. “Integrative co-evolution between mitochondria and their hosts” organized by Sergio A. Muñoz- The Forum is organized jointly by the International Gómez, Claudio H. Slamovits, and Andrew J. Society of Protistologists (ISoP), International Roger, and “Protists of Marine Sediments” orga- Society for Evolutionary Protistology (ISEP), nized by Jun Gong and Virginia Edgcomb. -

Van Leeuwenhoek's Microscopes

46 Chapter 4 Chapter 4 Van Leeuwenhoek’s Microscopes While I am writing this letter, I have 8 or 10 magnifying glasses lying about, which have been mounted in silver by me; and although I never received any instruction in working in any metal with a hammer or a file, still I mount my glasses, and my tools have been fitted in such a way that master goldsmiths say that they cannot emulate me. In a letter comparing his ability to see sperm with the results claimed by Nicolaas Hartsoeker (see chapter 6), Antoni van Leeuwenhoek wrote to the Royal Society about how well he made his simple microscopes. It is frequently said that he invented the microscope, but this is not true. He improved the single-lens microscope enormously, but the manufacture and use of magnify- ing lenses began much earlier. The First Microscopes: A Brief History Magnifying lenses of one type or another have been in use for thousands of years. The oldest known lenses – made of polished crystals, usually quartz – date from 700 BC and were found in the Assyrian empire, and later in Egypt, Greece and Babylon. The Greek comic playwright Aristophanes (446–386 BC) wrote that burning glasses for the starting of fires were on sale in the shops of Athens. It is believed that the necessary magnification for the delicate work of cutting precious stones in antiquity was done using glass flasks filled with water. The Roman Stoic philosopher, Seneca (± 4 BC–65 AD), wrote that small letters, however small and unclear they may be, became large and clear when viewed through a glass bowl filled with water. -

Conservation Update for Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Slide 1 Conservation Update Robert Hooke’s Micrographia London:1667 Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] Hello, my name is Eliza Gilligan and I am the Conservator for University Library Collections at the University of Virginia. This slide show is a “re-broadcast” of a presentation I made at a library staff “Town Meeting” on September 16, 2011. I hope my notes to the slides fill in the gaps left by the transition from live presentation to this show, but if you have a question, please feel free to email me <[email protected]>. I’d like to share a little bit of information about the process of conservation treatment and also a little bit of information about what a unique opportunity conservation treatment provides in terms of examining the components of a book, using my recent treatment of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia as an example. Conservation of this title and many volumes from our circulating collections were made possible by a generous gift from Kathy Duffy, friend of the University Library Slide 2 What is Micrographia? The landmark publication that initiated the field of microscopy. The first edition was published in London in 1665. Robert Hooke described his use of a microscope for direct observation, provided text of his findings but most importantly, large illustrations to demonstrate his findings. The UVa Library copy is from the second issue printed in 1667. Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] This book was brought to my attention by a faculty member of the Rare Book School who uses it every year in her History of Illustration class. -

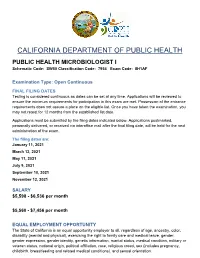

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC HEALTH PUBLIC HEALTH MICROBIOLOGIST I Schematic Code: SW50 Classification Code: 7954 Exam Code: 8H1AF

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH PUBLIC HEALTH MICROBIOLOGIST I Schematic Code: SW50 Classification Code: 7954 Exam Code: 8H1AF Examination Type: Open Continuous FINAL FILING DATES Testing is considered continuous as dates can be set at any time. Applications will be reviewed to ensure the minimum requirements for participation in this exam are met. Possession of the entrance requirements does not assure a place on the eligible list. Once you have taken the examination, you may not retest for 12 months from the established list date. Applications must be submitted by the filing dates indicated below. Applications postmarked, personally delivered, or received via interoffice mail after the final filing date, will be held for the next administration of the exam. The filing dates are: January 11, 2021 March 12, 2021 May 11, 2021 July 9, 2021 September 10, 2021 November 12, 2021 SALARY $5,598 - $6,536 per month $5,560 - $7,456 per month EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY The State of California is an equal opportunity employer to all, regardless of age, ancestry, color, disability (mental and physical), exercising the right to family care and medical leave, gender, gender expression, gender identity, genetic information, marital status, medical condition, military or veteran status, national origin, political affiliation, race, religious creed, sex (includes pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding and related medical conditions), and sexual orientation. WHO CAN APPLY Persons who meet the minimum qualifications as stated on this announcement may take this competitive examination. MINIMUM QUALIFICATIONS Possession of a valid Public Health Microbiologist's certificate issued by the California State Department of Public Health (Formerly the Department of Health Services.) (Possession of a Baccalaureate Degree with a major in Medical or Public Health Microbiology or equivalent subjects and six months' training in a public health laboratory or the equivalent are required for certification. -

Scientists Dissent List

A SCIENTIFIC DISSENT FROM DARWINISM “We are skeptical of claims for the ability of random mutation and natural selection to account for the complexity of life. Careful examination of the evidence for Darwinian theory should be encouraged.” This was last publicly updated April 2020. Scientists listed by doctoral degree or current position. Philip Skell* Emeritus, Evan Pugh Prof. of Chemistry, Pennsylvania State University Member of the National Academy of Sciences Lyle H. Jensen* Professor Emeritus, Dept. of Biological Structure & Dept. of Biochemistry University of Washington, Fellow AAAS Maciej Giertych Full Professor, Institute of Dendrology Polish Academy of Sciences Lev Beloussov Prof. of Embryology, Honorary Prof., Moscow State University Member, Russian Academy of Natural Sciences Eugene Buff Ph.D. Genetics Institute of Developmental Biology, Russian Academy of Sciences Emil Palecek Prof. of Molecular Biology, Masaryk University; Leading Scientist Inst. of Biophysics, Academy of Sci., Czech Republic K. Mosto Onuoha Shell Professor of Geology & Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Univ. of Nigeria Fellow, Nigerian Academy of Science Ferenc Jeszenszky Former Head of the Center of Research Groups Hungarian Academy of Sciences M.M. Ninan Former President Hindustan Academy of Science, Bangalore University (India) Denis Fesenko Junior Research Fellow, Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology Russian Academy of Sciences (Russia) Sergey I. Vdovenko Senior Research Assistant, Department of Fine Organic Synthesis Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry and Petrochemistry Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences (Ukraine) Henry Schaefer Director, Center for Computational Quantum Chemistry University of Georgia Paul Ashby Ph.D. Chemistry Harvard University Israel Hanukoglu Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Chairman The College of Judea and Samaria (Israel) Alan Linton Emeritus Professor of Bacteriology University of Bristol (UK) Dean Kenyon Emeritus Professor of Biology San Francisco State University David W. -

Data-Mining Approaches Reveal Hidden Families of Proteases in The

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 5, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Letter Data-Mining Approaches Reveal Hidden Families of Proteases in the Genome of Malaria Parasite Yimin Wu,1,4 Xiangyun Wang,2 Xia Liu,1 and Yufeng Wang3,5 1Department of Protistology, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia 20110, USA; 2EST Informatics, Astrazeneca Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, Delaware 19810, USA; 3Department of Bioinformatics, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Virginia 20110, USA The search for novel antimalarial drug targets is urgent due to the growing resistance of Plasmodium falciparum parasites to available drugs. Proteases are attractive antimalarial targets because of their indispensable roles in parasite infection and development,especially in the processes of host e rythrocyte rupture/invasion and hemoglobin degradation. However,to date,only a small number of protease s have been identified and characterized in Plasmodium species. Using an extensive sequence similarity search,we have identifi ed 92 putative proteases in the P. falciparum genome. A set of putative proteases including calpain,metacaspase,and s ignal peptidase I have been implicated to be central mediators for essential parasitic activity and distantly related to the vertebrate host. Moreover,of the 92,at least 88 have been demonstrate d to code for gene products at the transcriptional levels,based upon the microarray and RT-PCR results,an d the publicly available microarray and proteomics data. The present study represents an initial effort to identify a set of expressed,active,and essential proteases as targets for inhibitor-based drug design. [Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.] Malaria remains one of the most dangerous infectious diseases metalloprotease (falcilysin; Eggleson et al.