Introduction: Charting the History of the Equestrian Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome Vs Rome Ing Late Romans Come from the Cover of the Roman Empire in the Middle of the Fourth

THE BATTLE OF MURSA MAJOR THEME Left-handed warriors? Yes, the image has been mirrored. These charg- Rome vs Rome ing Late Romans come from the cover of The Roman Empire in the middle of the fourth Ancient Warfare VI-5. V century found itself in crisis. It had been split by Constantine the Great between his three surviving sons, Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans. However, soon the brothers were at each other’s throats vying for power. By David Davies onstantine II was defeated by the forces of Constans in AD 340, leav- ingC him in control of the western half of the Roman Empire. Howev- er in AD 350, he in turn was usurped by one of his own generals, Mag- nentius, who took the title Emperor of the West- ern Empire. Constans fled but was ambushed and killed by a troop of light cavalry while his party at- tempted to cross the Pyrenees. Magnentius quickly wooed support from the provinces in Britannia, Gaul, and Hispania with his lax approach to pagan- ism. Other provinces remained hesitant and many remained loyal to the Constan- tinian dynasty. The new Western Roman Emperor tried to exert his control directly by appointing his own men to command provinces and legions, ex- ecuting commanders loyal to the old regime, and by moving his forces into poten- tial rebel territories. When Nepotianus (a nephew of Constantine the Great) stormed Rome with a band of gladiators and pro- claimed himself em- peror, the revolt was swiftly dealt with. It became clear to 1 Wargames, soldiers & strategy 95 Cataphracts from the Eastern and Western Roman Empires square off. -

Narratology and the End of Monarchy in AVC 1

Luke Patient Classics Department [email protected] University of Arizona Narratology and the End of Monarchy in AVC 1 I. The section of the narrative text to be considered ( AVC 1.59.1, 6-11): 1. Brutus illis luctu occupatis cultrum ex volnere Lucretiae extractum, manantem cruore prae se tenens, "Per hunc" inquit "castissimum ante regiam iniuriam sanguinem iuro, vosque, di, testes facio me L. Tarquinium Superbum cum scelerata coniuge et omni liberorum stirpe ferro igni quacumque dehinc vi possim exsecuturum, nec illos nec alium quemquam regnare Romae passurum." … Vbi eo ventum est, quacumque incedit armata multitudo, pavorem ac tumultum facit; rursus ubi anteire primores civitatis vident, quidquid sit haud temere esse rentur. Nec minorem motum animorum Romae tam atrox res facit quam Collatiae fecerat; ergo ex omnibus locis urbis in forum curritur. Quo simul ventum est, praeco ad tribunum celerum, in quo tum magistratu forte Brutus erat, populum advocavit. Ibi oratio habita nequaquam eius pectoris ingeniique quod simulatum ad eam diem fuerat, de vi ac libidine Sex. Tarquini, de stupro infando Lucretiae et miserabili caede, de orbitate Tricipitini cui morte filiae causa mortis indignior ac miserabilior esset. Addita superbia ipsius regis miseriaeque et labores plebis in fossas cloacasque exhauriendas demersae; Romanos homines, victores omnium circa populorum, opifices ac lapicidas pro bellatoribus factos. Indigna Ser. Tulli regis memorata caedes et inuecta corpori patris nefando vehiculo filia, invocatique ultores parentum di. His atrocioribusque, credo, aliis, quae praesens rerum indignitas haudquaquam relatu scriptoribus facilia subicit, memoratis, incensam multitudinem perpulit ut imperium regi abrogaret exsulesque esse iuberet L. Tarquinium cum coniuge ac liberis. -

ROMAN POLITICS DURING the JUGURTHINE WAR by PATRICIA EPPERSON WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State

ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR By PATRICIA EPPERSON ,WINGATE Bachelor of Arts in Education Northeastern Oklahoma State University Tahlequah, Oklahoma 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1975 SEP Ji ·J75 ROMAN POLITICS DURING THE JUGURTHINE WAR Thesis Approved: . Dean of the Graduate College 91648 ~31 ii PREFACE The Jugurthine War occurred within the transitional period of Roman politics between the Gracchi and the rise of military dictators~ The era of the Numidian conflict is significant, for during that inter val the equites gained political strength, and the Roman army was transformed into a personal, professional army which no longer served the state, but dedicated itself to its commander. The primary o~jec tive of this study is to illustrate the role that political events in Rome during the Jugurthine War played in transforming the Republic into the Principate. I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Neil Hackett, for his patient guidance and scholarly assistance, and to also acknowledge the aid of the other members of my counnittee, Dr. George Jewsbury and Dr. Michael Smith, in preparing my final draft. Important financial aid to my degree came from the Dr. Courtney W. Shropshire Memorial Scholarship. The Muskogee Civitan Club offered my name to the Civitan International Scholarship Selection Committee, and I am grateful for their ass.istance. A note of thanks is given to the staff of the Oklahoma State Uni versity Library, especially Ms. Vicki Withers, for their overall assis tance, particularly in securing material from other libraries. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

The Late Republic – Crises and Civil Wars a Society Falls Apart in Italy

The Late Republic – Crises and Civil Wars A Society Falls Apart In Italy, much had changed after Rome rose to a world power. In the long wars, many peasants and their sons had died. Others had not been able to properly cultivate their farms for years. More and more small farmers left the countryside. In their place, many large farms arose, because large landowners had bought up the land of indebted peasants, forcibly driven some farmers out, and laid claim to large portions of state-owned land for themselves. Their standard of living rose, because they specialized themselves in certain products. They grew wine-grapes and olives on a grand scale, or reorganized themselves toward livestock. Around the cities, there were large landowners who obtained high profits by raising poultry and fish. Such large landowners usually owned several farms, which were managed by administrators, while they themselves pursued political business in Rome. On their estates, slaves worked, who were obtained either as prisoners of war or on the slave markets. According to careful analysis, in the time between 200 B.C. and 150 B.C., approximately 250,000 prisoners of war were brought to Italy as slaves. In the following 100 years, more than 500,000 slaves – mainly from Asia Minor – came to Rome. Especially the small farmers suffered in this situation. Earlier, they had gotten for themselves additional income as daily workers on the estates, but now they were needed there, at most, only for harvest. So many had to give up their farms, and moved with their families to Rome. -

Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, C.319–50 BC

Ex senatu eiecti sunt: Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, c.319–50 BC Lee Christopher MOORE University College London (UCL) PhD, 2013 1 Declaration I, Lee Christopher MOORE, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Thesis abstract One of the major duties performed by the censors of the Roman Republic was that of the lectio senatus, the enrolment of the Senate. As part of this process they were able to expel from that body anyone whom they deemed unequal to the honour of continued membership. Those expelled were termed ‘praeteriti’. While various aspects of this important and at-times controversial process have attracted scholarly attention, a detailed survey has never been attempted. The work is divided into two major parts. Part I comprises four chapters relating to various aspects of the lectio. Chapter 1 sees a close analysis of the term ‘praeteritus’, shedding fresh light on senatorial demographics and turnover – primarily a demonstration of the correctness of the (minority) view that as early as the third century the quaestorship conveyed automatic membership of the Senate to those who held it. It was not a Sullan innovation. In Ch.2 we calculate that during the period under investigation, c.350 members were expelled. When factoring for life expectancy, this translates to a significant mean lifetime risk of expulsion: c.10%. Also, that mean risk was front-loaded, with praetorians and consulars significantly less likely to be expelled than subpraetorian members. -

Livy's Early History of Rome: the Horatii & Curiatii

Livy’s Early History of Rome: The Horatii & Curiatii (Book 1.24-26) Mary Sarah Schmidt University of Georgia Summer Institute 2016 [1] The Horatii and Curiatii This project is meant to highlight the story of the Horatii and Curiatii in Rome’s early history as told by Livy. It is intended for use with a Latin class that has learned the majority of their Latin grammar and has knowledge of Rome’s history surrounding Julius Caesar, the civil wars, and the rise of Augustus. The Latin text may be used alone or with the English text of preceding chapters in order to introduce and/or review the early history of Rome. This project can be used in many ways. It may be an opportunity to introduce a new Latin author to students or as a supplement to a history unit. The Latin text may be used on its own with an historical introduction provided by the instructor or the students may read and study the events leading up to the battle of the Horatii and Curiatii as told by Livy. Ideally, the students will read the preceding chapters, noting Livy’s intention of highlighting historical figures whose actions merit imitation or avoidance. This will allow students to develop an understanding of what, according to Livy and his contemporaries, constituted a morally good or bad Roman. Upon reaching the story of the Horatii and Curiatii, not only will students gain practice and understanding of Livy’s Latin literary style, but they will also be faced with the morally confusing Horatius. -

Seutonius: Lives of the Twelve Caesars 1

Seutonius: Lives of the Twelve Caesars 1 application on behalf of his friend to the emperor THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS Trajan, for a mark of favor, he speaks of him as "a By C. Suetonius Tranquillus most excellent, honorable, and learned man, whom he had the pleasure of entertaining under The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. his own roof, and with whom the nearer he was brought into communion, the more he loved Revised and corrected by T. Forester, Esq., A.M. 1 him." CAIUS JULIUS CAESAR. ................................................. 2 The plan adopted by Suetonius in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars, led him to be more diffuse on OCTAVIUS CAESAR AUGUSTUS. .................................. 38 their personal conduct and habits than on public TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR. ............................................ 98 events. He writes Memoirs rather than History. CAIUS CAESAR CALIGULA. ........................................ 126 He neither dwells on the civil wars which sealed TIBERIUS CLAUDIUS DRUSUS CAESAR. ..................... 146 the fall of the Republic, nor on the military NERO CLAUDIUS CAESAR. ........................................ 165 expeditions which extended the frontiers of the SERGIUS SULPICIUS GALBA. ..................................... 194 empire; nor does he attempt to develop the causes of the great political changes which A. SALVIUS OTHO. .................................................... 201 marked the period of which he treats. AULUS VITELLIUS. ..................................................... 206 When we stop to gaze in a museum or gallery on T. FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS AUGUSTUS. ..................... 212 the antique busts of the Caesars, we perhaps TITUS FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS AUGUSTUS. ............... 222 endeavor to trace in their sculptured TITUS FLAVIUS DOMITIANUS. .................................. 229 physiognomy the characteristics of those princes, who, for good or evil, were in their times masters of the destinies of a large portion of the PREFACE human race. -

THE TALE of SAINT ABEBCIUS. the Chief Authority for the Life of This

THE TALE OF SAINT ABERCIUS. 339 THE TALE OF SAINT ABEBCIUS. THE chief authority for the life of this saint is the biography by Symeon Metaphrastes, written about 900-50 A.D. It quotes the epitaph on the saint's tomb, and the question whether this epitaph is an original document of the second century A.D., or a later forgery, is one of the utmost importance for the early history of the Christian church, and of many literary points connected with it. The document is not very easily accessible, so that it may be well to quote it as it is given in the Life by Metaphrastes; the criticism of the text has been to a certain extent advanced by the metrical restorations proposed by Pitra and others.1 'E/icXe/eTr;? iroXeas •jroXirrj^ TO'8' eirouqaa ^a>i>, Xv e%co iecupq> <TU>f*aTO<; ivddSe Bicnp, TOVVO/M A/8ep«tos d we /AadrjTT]? Hoifievo'i dyvov, os {36<rK€t, irpofSaTdtv dyeXa<s ovpeai TreStcu? Te" 6<f>6aX- fiov; os e\ei fieydXow} iravra KaOopotovra1;. OVTOS yap f-e eSiSalje ypdfifiara TriaTa' ets 'VwfirjV os eire/M'yfrev ifie a9p7Jtraf ica\ fBaol~kL<T<rav IBeiv ^pvcrocrToXo ^ Xaov 8' elSof eicei Xafiirpav a<bpayi§a e^ovra' ical 2U/SM;S X(*>Pa<> «oW Kal aarea irdvTa, Nt'crt/3tv Ev^pdrrjv Sta/3d<;' irdv- 7as 8' eaj(pv avvofirjyvpovi YlavXov e<ra>0ev. IL'ffTts 8e iravrl irporjye Kal irape6r}Ke Tpo<f)r)v, l%8vv airo •mjyr)'; ira/xfieyiOr] KaOapbv ov iBpd^aro Tlapdevos dyvtj, Kal TOVTOV eVeSaJKe <f>i\ot,<: iadieiv hiairavTO';- oivov ^prjarbv ej(pu<ra Kepao-pa ScBovaa //.«••?•' aprov. -

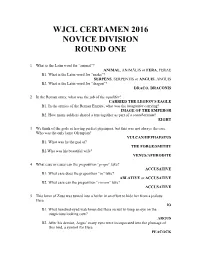

Wjcl Certamen 2016 Novice Division Round One

WJCL CERTAMEN 2016 NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What is the Latin word for “animal”? ANIMAL, ANIMĀLIS or FERA, FERAE B1. What is the Latin word for “snake”? SERPĒNS, SERPENTIS or ANGUIS, ANGUIS B2. What is the Latin word for “dragon”? DRACO, DRACŌNIS 2. In the Roman army, what was the job of the aquilifer? CARRIED THE LEGION’S EAGLE B1. In the armies of the Roman Empire, what was the imaginifer carrying? IMAGE OF THE EMPEROR B2. How many soldiers shared a tent together as part of a contubernium? EIGHT 3. We think of the gods as having perfect physiques, but this was not always the case. Who was the only lame Olympian? VULCAN/HEPHAESTUS B1. What was he the god of? THE FORGE/SMITHY B2.Who was his beautiful wife? VENUS/APHRODITE 4. What case or cases can the preposition “prope” take? ACCUSATIVE B1. What case does the preposition “in” take? ABLATIVE or ACCUSATIVE B2. What case can the preposition “circum” take? ACCUSATIVE 5. This lover of Zeus was turned into a heifer in an effort to hide her from a jealous Hera. IO B1. What hundred-eyed watchman did Hera recruit to keep an eye on the suspicious looking cow? ARGUS B2. After his demise, Argus’ many eyes were incorporated into the plumage of this bird, a symbol for Hera PEACOCK 6. Which of the following words differs from the others in use and function? Quinque, Tertius, Decem, Sex TERTIUS B1. What type of number is tertius? ORDINAL [accept definitions/explanations of what an ordinal is] B2. -

Me:'J-At-Arms Series 247 Romano-Byzantine Armies 4Th-9Th Centuries

Gm:m MIUTARY ME:'J-AT-ARMS SERIES 247 ROMANO-BYZANTINE ARMIES 4TH-9TH CENTURIES [) \\lD "'COLI,f. PIID\"eiCS \IcBRIDf. EDITOR: MARTlN WINDROW ~ 247 ROMANO-BYZANTINE ARMIES 4TH-9TH CENTURIES Text by DAVID NICOLLE PHD Colour plates by ANGUS McBRIDE ~t1tj ....."" Dod,ctI'H>n .... , .. t JIM F... <.ii... lludl JOt<;o..._-.~,..-.,.0\ l(;opo........~'q' j .... 1I.Jy. ..,./f.q! fl.-t<'<t ~1"'7·I.J"'II '""""" ....... _ ....\jooft_.. 6oio.s..:.., .... (It~f-f_·._ha ......._.....,,--~ '"' .. ...._j _ .."'-P!.... l:Irooop: "-'I<&. I....... C.utf; ................ ""bIO<oo__• lot .... O"'.".r in"..."....UIN _ ·....-.... b ) . G,.,~J ",,,in{tI. 'lIa/y-' ., 001 d«tn>W.<lo<1riboI, <-.al. -.:lo.-.I ..,......-..,.,iup-........., ... (Rober, 1I.....'n'~' ............ ~_,""pnorP'" "'_ ""'~... !Io ..._. ~.....",rirt oJooolJ "" ~"' ~,'OIhIO<O- ,h'ist's '\IOle R""I0'" m.y ,,,rc to nO," {~" (~" orig;n.ll"'in,ing< ISI<r> , IU.l""" f",m ,,~'C~ I~" ""I"", pl.,,,, in l~", I,,,o~ "'n" p,,,poml ... .-,.il.ble ror Pli....u"le. All fOPlod"'UOfl c<>pyriJht .. ho~""'Ill.........d It) the publ..h.... All enquiries "'DUld bo: .ddrastd t(" PO 80.0: "IS, """"'lholtlwn, f Su..., 8:-.. ..; .>51- Thc~rq .... 1hat tMJ""-" _ .....to .... ~nceuporl IM"",tla r............... houaL; t, _boo!"","" \1.... J*- oo: ",. "~n \I........ G-o...... c.taloo,;o>t ~mftOt. ~ blltohi'" 1...1. \hebd;n , Fulhom Jr. ...d. I_S\\J'1l1l ROMANO-BYZANTINE ARMIES INTRODUCTION gorri",m dUlies dccline<l;n qu.l,,). Mun.. hil" 10le Roman Empcrors gcnc....lIy o,,"cd ,heir l"""ion !O lh. orm)'; power ofien 10)' ;n lhe h.nd. -

Roman History

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028270894 Cornell University Library DG 207.L5F85 1899 Roman histor 3 1924 028 270 894 Titus Livius Roman History The World's TITUS LIVIUS. Photogravure from an engraving in a seventeenth-century edition of Livy's History. Roman History By Titus Livius Translated by John Henry Freese, Alfred John Church, and William Jackson Brodribb With a Critical and Biographical Introduction and Notes by Duffield Osborne Illustrated New York D. Appleton and Company 1899 LIVY'S HISTORY the lost treasures of classical literature, it is doubtful OFwhether any are more to be regretted than the missing books of Livy. That they existed in approximate en- tirety down to the fifth century, and possibly even so late as the fifteenth, adds to this regret. At the same time it leaves in a few sanguine minds a lingering hope that some un- visited convent or forgotten library may yet give to the world a work that must always be regarded as one of the greatest of Roman masterpieces. The story that the destruction of Livy was effected by order of Pope Gregory I, on the score of the superstitions contained in the historian's pages, never has been fairly substantiated, and therefore I prefer to acquit that pontiff of the less pardonable superstition involved in such an act of fanatical vandalism. That the books preserved to us would be by far the most objectionable from Gregory's alleged point of view may be noted for what it is worth in favour of the theory of destruction by chance rather than by design.