Narratology and the End of Monarchy in AVC 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 History of Rome You Will Find in This Packet

Reading for Monday 4/23/12 A e History of Rome A You will find in this packet three different readings. 1) Augustus’ autobiography. which he had posted for all to read at the end of his life: the Res Gestae (“Deeds Accomplished”). 2) A few passages from Vergil’s Aeneid (the epic telling the story of Aeneas’ escape from Troy and journey West to found Rome. The passages from the Aeneid are A) prophecy of the glory of Rome told by Jupiter to Venus (Aeneas’ mother). B) A depiction of the prophetic scenes engraved on Aeneas’ shield by the god Vulcan. The most important part of this passage to read is the depiction of the Battle of Actium as portrayed on Aeneas’ shield. (I’ve marked the beginning of this bit on your handout). Of course Aeneas has no idea what is pictured because it is a scene from the future... Take a moment to consider how the Battle of Actium is portrayed by Vergil in this scene! C) In this scene, Aeneas goes down to the Underworld to see his father, Anchises, who has died. While there, Aeneas sees the pool of Romans waiting to be born. Anchises speaks and tells Aeneas about all of his descendants, pointing each of them out as they wait in line for their birth. 3) A passage from Horace’s “Song of the New Age”: Carmen Saeculare Important questions to ask yourself: Is this poetry propaganda? What do you take away about how Augustus wanted to be viewed, and what were some of the key themes that the poets keep repeating about Augustus or this new Golden Age? Le’,s The Au,qustan Age 195. -

Livy's Early History of Rome: the Horatii & Curiatii

Livy’s Early History of Rome: The Horatii & Curiatii (Book 1.24-26) Mary Sarah Schmidt University of Georgia Summer Institute 2016 [1] The Horatii and Curiatii This project is meant to highlight the story of the Horatii and Curiatii in Rome’s early history as told by Livy. It is intended for use with a Latin class that has learned the majority of their Latin grammar and has knowledge of Rome’s history surrounding Julius Caesar, the civil wars, and the rise of Augustus. The Latin text may be used alone or with the English text of preceding chapters in order to introduce and/or review the early history of Rome. This project can be used in many ways. It may be an opportunity to introduce a new Latin author to students or as a supplement to a history unit. The Latin text may be used on its own with an historical introduction provided by the instructor or the students may read and study the events leading up to the battle of the Horatii and Curiatii as told by Livy. Ideally, the students will read the preceding chapters, noting Livy’s intention of highlighting historical figures whose actions merit imitation or avoidance. This will allow students to develop an understanding of what, according to Livy and his contemporaries, constituted a morally good or bad Roman. Upon reaching the story of the Horatii and Curiatii, not only will students gain practice and understanding of Livy’s Latin literary style, but they will also be faced with the morally confusing Horatius. -

Romana Stasolla, Stefano Tortorella Direttore Responsabile: Domenico Palombi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository NUOVA SERIE Rivista del Dipartimento di Scienze dell’antichità Sezione di Archeologia Fondatore: GIULIO Q. GIGLIOLI Direzione Scientifica MARIA CRISTINA BIELLA, ENZO LIPPOLIS, LAURA MICHETTI, GLORIA OLCESE, DOMENICO PALOMBI, MASSIMILIANO PAPINI, MARIA GRAZIA PICOZZI, FRANCESCA ROMANA STASOLLA, STEFANO TORTORELLA Direttore responsabile: DOMENICO PALOMBI Redazione: FABRIZIO SANTI, FRANCA TAGLIETTI Vol. LXVIII - n.s. II, 7 2017 «L’ERMA» di BRETSCHNEIDER - ROMA Comitato Scientifico PIERRE GROS, SYBILLE HAYNES, TONIO HÖLSCHER, METTE MOLTESEN, STÉPHANE VERGER Il Periodico adotta un sistema di Peer-Review Archeologia classica : rivista dell’Istituto di archeologia dell’Università di Roma. - Vol. 1 (1949). - Roma : Istituto di archeologia, 1949. - Ill.; 24 cm. - Annuale. - Il complemento del titolo varia. - Dal 1972: Roma: «L’ERMA» di Bretschneider. ISSN 0391-8165 (1989) CDD 20. 930.l’05 ISBN CARTACEO 978-88-913-1563-2 ISBN DIGITALE 978-88-913-1567-0 ISSN 0391-8165 © COPYRIGHT 2017 - SAPIENZA - UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA Aut. del Trib. di Roma n. 104 del 4 aprile 2011 Volume stampato con contributo di Sapienza - Università di Roma INDICE DEL VOLUME LXVIII ARTICOLI AMBROGI A. (con un’appendice di FERRO C.), Un rilievo figurato di età tardo- repubblicana da un sepolcro dell’Appia antica ............................................... p. 143 BALDASSARRI P., Lusso privato nella tarda antichità: le piccole terme di Palazzo Valentini e un pavimento in opus sectile con motivi complessi...................... » 245 BARATTA G., Falere tardo-antiche ispaniche con quattro passanti angolari: aggiornamenti e ipotesi sulla funzionalità del tipo ......................................... » 289 BARBERA M., Prime ipotesi su una placchetta d’avorio dal Foro Romano ......... -

Seutonius: Lives of the Twelve Caesars 1

Seutonius: Lives of the Twelve Caesars 1 application on behalf of his friend to the emperor THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS Trajan, for a mark of favor, he speaks of him as "a By C. Suetonius Tranquillus most excellent, honorable, and learned man, whom he had the pleasure of entertaining under The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. his own roof, and with whom the nearer he was brought into communion, the more he loved Revised and corrected by T. Forester, Esq., A.M. 1 him." CAIUS JULIUS CAESAR. ................................................. 2 The plan adopted by Suetonius in his Lives of the Twelve Caesars, led him to be more diffuse on OCTAVIUS CAESAR AUGUSTUS. .................................. 38 their personal conduct and habits than on public TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR. ............................................ 98 events. He writes Memoirs rather than History. CAIUS CAESAR CALIGULA. ........................................ 126 He neither dwells on the civil wars which sealed TIBERIUS CLAUDIUS DRUSUS CAESAR. ..................... 146 the fall of the Republic, nor on the military NERO CLAUDIUS CAESAR. ........................................ 165 expeditions which extended the frontiers of the SERGIUS SULPICIUS GALBA. ..................................... 194 empire; nor does he attempt to develop the causes of the great political changes which A. SALVIUS OTHO. .................................................... 201 marked the period of which he treats. AULUS VITELLIUS. ..................................................... 206 When we stop to gaze in a museum or gallery on T. FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS AUGUSTUS. ..................... 212 the antique busts of the Caesars, we perhaps TITUS FLAVIUS VESPASIANUS AUGUSTUS. ............... 222 endeavor to trace in their sculptured TITUS FLAVIUS DOMITIANUS. .................................. 229 physiognomy the characteristics of those princes, who, for good or evil, were in their times masters of the destinies of a large portion of the PREFACE human race. -

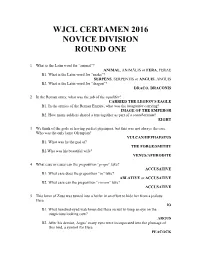

Wjcl Certamen 2016 Novice Division Round One

WJCL CERTAMEN 2016 NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. What is the Latin word for “animal”? ANIMAL, ANIMĀLIS or FERA, FERAE B1. What is the Latin word for “snake”? SERPĒNS, SERPENTIS or ANGUIS, ANGUIS B2. What is the Latin word for “dragon”? DRACO, DRACŌNIS 2. In the Roman army, what was the job of the aquilifer? CARRIED THE LEGION’S EAGLE B1. In the armies of the Roman Empire, what was the imaginifer carrying? IMAGE OF THE EMPEROR B2. How many soldiers shared a tent together as part of a contubernium? EIGHT 3. We think of the gods as having perfect physiques, but this was not always the case. Who was the only lame Olympian? VULCAN/HEPHAESTUS B1. What was he the god of? THE FORGE/SMITHY B2.Who was his beautiful wife? VENUS/APHRODITE 4. What case or cases can the preposition “prope” take? ACCUSATIVE B1. What case does the preposition “in” take? ABLATIVE or ACCUSATIVE B2. What case can the preposition “circum” take? ACCUSATIVE 5. This lover of Zeus was turned into a heifer in an effort to hide her from a jealous Hera. IO B1. What hundred-eyed watchman did Hera recruit to keep an eye on the suspicious looking cow? ARGUS B2. After his demise, Argus’ many eyes were incorporated into the plumage of this bird, a symbol for Hera PEACOCK 6. Which of the following words differs from the others in use and function? Quinque, Tertius, Decem, Sex TERTIUS B1. What type of number is tertius? ORDINAL [accept definitions/explanations of what an ordinal is] B2. -

Roman History

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tlie Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924028270894 Cornell University Library DG 207.L5F85 1899 Roman histor 3 1924 028 270 894 Titus Livius Roman History The World's TITUS LIVIUS. Photogravure from an engraving in a seventeenth-century edition of Livy's History. Roman History By Titus Livius Translated by John Henry Freese, Alfred John Church, and William Jackson Brodribb With a Critical and Biographical Introduction and Notes by Duffield Osborne Illustrated New York D. Appleton and Company 1899 LIVY'S HISTORY the lost treasures of classical literature, it is doubtful OFwhether any are more to be regretted than the missing books of Livy. That they existed in approximate en- tirety down to the fifth century, and possibly even so late as the fifteenth, adds to this regret. At the same time it leaves in a few sanguine minds a lingering hope that some un- visited convent or forgotten library may yet give to the world a work that must always be regarded as one of the greatest of Roman masterpieces. The story that the destruction of Livy was effected by order of Pope Gregory I, on the score of the superstitions contained in the historian's pages, never has been fairly substantiated, and therefore I prefer to acquit that pontiff of the less pardonable superstition involved in such an act of fanatical vandalism. That the books preserved to us would be by far the most objectionable from Gregory's alleged point of view may be noted for what it is worth in favour of the theory of destruction by chance rather than by design. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Latin cults through Roman eyes Myth, memory and cult practice in the Alban hills Hermans, A.M. Publication date 2017 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hermans, A. M. (2017). Latin cults through Roman eyes: Myth, memory and cult practice in the Alban hills. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 CHAPTER IV: Jupiter Latiaris and the feriae Latinae: celebrating and defining Latinitas The region of the Alban hills, as we have seen in previous chapters, has been interpreted by both modern and ancient authors as a deeply religious landscape, in which mythical demigods and large protective deities resided next to and in relation to each other. -

Stories from Livy Numa Pompilius and the Nymph Egeria Stories from Livy

STORIES FROM LIVY NUMA POMPILIUS AND THE NYMPH EGERIA STORIES FROM LIVY BY ALFRED J. CHURCH with illustrations from designs by Pinelli YESTERDAY’S CLASSICS CHAPEL HILL, NORTH CAROLINA Cover and arrangement © 2008 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC. Th is edition, fi rst published in 2008 by Yesterday’s Classics, an imprint of Yesterday’s Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Dodd, Mead & Company in 1893. For the complete listing of the books that are published by Yesterday’s Classics, please visit www.yesterdaysclassics.com. Yesterday’s Classics is the publishing arm of the Baldwin Online Children’s Literature Project which presents the complete text of hundreds of classic books for children at www.mainlesson.com. ISBN-10: 1-59915-078-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-59915-078-9 Yesterday’s Classics, LLC PO Box 3418 Chapel Hill, NC 27515 TO HENRY FRANCIS CHURCH BEST OF BROTHERS CONTENTS I. The Story of Romulus and Numa . .1 II. The Story of Alba . .16 III. The Story of the Elder Tarquin . .33 IV. The Story of Servius . .43 V. The Story of Brutus . .51 VI. The Story of Lars Porsenna . .64 VII. The Story of Coriolanus . .77 VIII. The Story of the Fabii . .90 IX. The Story of Cincinnatus . .95 X. The Story of the Decemvirs and of Virginia . 104 XI. The Story of Veii . 115 XII. The Story of Camillus . 129 XIII. The Story of Rome and the Gauls . 136 XIV. The Story of Rome and the Gauls (continued) . .144 XV. The Story of Manlius of the Twisted Chain . -

Rape Culture in Ancient Rome Molly Ashmore Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Classics Honors Papers Classics Department 2015 Rape Culture in Ancient Rome Molly Ashmore Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/classicshp Recommended Citation Ashmore, Molly, "Rape Culture in Ancient Rome" (2015). Classics Honors Papers. Paper 3. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/classicshp/3 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. 1 Rape Culture in Ancient Rome Senior Honors Thesis Presented by Molly Rose Ashmore Department of Classical Studies Advisor: Professor Darryl Phillips Reader: Professor Tobias Myers Connecticut College New London, Connecticut April 30th, 2015 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Roman Sexuality and the Lex Julia de Adulteriis Coercendis 15 Chapter 2: Rape Narratives in Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita 33 Chapter 3: Sexual Violence in Ovid’s Poetry 56 Chapter 4: Stuprum in Roman Art 77 Conclusion 93 Bibliography 96 Images 100 Image Sources 106 3 Introduction American culture in the 1970’s witnessed a pivotal shift in the public understanding of sexual violence. The second wave feminist movement brought about the first public discussions of rape as a personal experience and a widespread social problem.1 Modern understanding and modes of criticism of rape largely stem from this moment that publicized issues, which previously had been private matters. -

Livy 1.58 When a Few Days Had Gone By, Sextus Tarquinius, Without Letting Collatinus Know, Took a Single Attendant and Went to Collatia

The Foundations of Rome from Kingship to Republic 753-440 BC Key sources: Source Period Aims and agenda Key problems Views on Rome Dionysius Lived Wrote the Dionysius’ history Overall, (of Halicarnassus*) 60 BC- ‘Roman History’ has a huge scope, so Dionysius 7 BC from Rome’s he had to collect makes the mythical evidence second point that beginnings to the hand from earlier Romans first Punic War texts. derive from (264 BC). Greek Dionysius’ Greek origins and Emphasises the background shapes benefit positive qualities the way he presents form Greek of Roman the Romans. virtues. conquerors and traced their Dionysius embraces ancestors back to Roman origin myths Greeks. into his history, such *Halicarnassus is as Romulus and modern day Bodrum, His work and Remus. Turkey. The same place Livy’s are our only that the historian continuous Herodotus was from. ancient histories of Rome. Livy Lived Livy’s writings Livy is heavily critical In sum, Livy 59 BC- contain of Rome’s enemies manipulates AD 17 elementary because of his myth when mistakes on Roman bias. writing military matters, about indicating that he Rome’s probably never Like Dionysius, Livy’s early kings, served in history includes to glorify the Roman army. mythological Roman elements on the ancestry. Chronological but founding of Rome, narrative style which are based on that is highly Greek myths e.g. descriptive. Aeneas as the Roman founder. Livy’s history emphasizes the Only 35 of Livy’s 142 great triumphs of books survive. Rome because he was writing under the reign of Augustus. 2 Time line of the Roman Kings: Legendary (753-616 BC) and Etruscan (616-509 BC) Portrait Name Lifespan Reign Succession c.772 BC 753 BC Proclaimed himself king after Romulus to to murdering his brother, Remus. -

History of Rome (Ab Urbe Conditā)

History Reading #4 – From Romulus to Brutus Livy – History of Rome (Ab Urbe Conditā) Book I – Rome Under the Kings PREFACE Whether the task I have undertaken of writing a complete history of the Roman people from the very commencement of its existence will reward me for thelabour spent on it, I neither know for certain, nor if I did know would I venture to say. For I see that this is an old‐established and a common practice, each fresh writer being invariably persuaded that he will either attain greater certainty in the materials of his narrative, or surpass the rudeness of antiquity in the excellence of his style. However this may be, it will still be a great satisfaction to me to have taken my part, too, in investing, to the utmost of my abilities, the annals of the foremost nation in the world with a deeper interest; and if in such a crowd of writers my own reputation is thrown into the shade, I would console myself with the renown and greatness of those who eclipse my fame. The subject, moreover, is one that demands immense labour. It goes back beyond 700 years and, after starting from small and humble beginnings, has grown to such dimensions that it begins to be overburdened by its greatness. I have very little doubt, too, that for the majority of my readers the earliest times and those immediately succeeding, will possess little attraction; they will hurry on to these modern days in which the might of a long paramount nation is wasting by internal decay. -

Hudson Dissertation Final Version

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title On the Way: a Poetics of Roman Transportation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4rp2b2ws Author Hudson, Jared McCabe Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California On the Way: a Poetics of Roman Transportation by Jared McCabe Hudson A dissertation in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ellen Oliensis, chair Professor Maurizio Bettini Professor Dylan Sailor Professor Carlos Noreña Spring 2013 On the Way: a Poetics of Roman Transportation © 2013 by Jared McCabe Hudson Abstract On the Way: a Poetics of Roman Transportation By Jared McCabe Hudson Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Ellen Oliensis, Chair The first chapter examines the role played by the litter (lectica) and sedan chair (sella) in Roman literature and culture. The portrait of the wealthy freedman, lounging in his deluxe octaphoros (litter carried by eight imported slaves), is one which appears repeatedly, taking shape in the late Republic and reaching a climax of frequency in the satires of Juvenal and the epigrams of Martial, in the late first century CE. While by this stage the conveyance undeniably functions as a satirical symbol, the origins and constructedness of its role as such have been surprisingly under-examined by modern scholars. In order to excavate the litter’s developing identity, I first unravel Roman accounts of the vehicle’s origins.