Konstantinopolis'te Ulaşim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nika Riot Author(S): J

The Nika Riot Author(s): J. B. Bury Source: The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 17 (1897), pp. 92-119 Published by: The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/623820 . Accessed: 31/07/2013 12:43 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Hellenic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.248.155.225 on Wed, 31 Jul 2013 12:43:10 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 92 THE NIKA RIOT. THE NIKA RIOT. THE great popular insurrection which shook the throne of Justinian in the fifth year of his reign and laid in ashes the imperial quarter of Constan- tinople has been treated again and again by historians, but never in a com- pletely satisfactory way.' Its import has not been quite clearly grasped, owing to an imperfect apprehension of the meaning of the circus factions; the sources have not been systematically correlated; the chronology has not been finally fixed; and the topographical questions have caused much perplexity. -

Χρονολόγηση Γεωγραφικός Εντοπισμός Great Palace In

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Westbrook Nigel (21/12/2007) Για παραπομπή : Westbrook Nigel , "Great Palace in Constantinople", 2007, Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Κωνσταντινούπολη URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=12205> Great Palace in Constantinople Περίληψη : The Great Palace of the byzantine emperors was the first imperial palace in Constantinople. It was founded as such, supposedly by Constantine the Great, in his newly founded capital. It remained the primary imperial palace in Constantinople up to and beyond the reign of emperor Constantine VII (913-959), in whose Book of Ceremonies its halls are named. Χρονολόγηση 4th-10th c. Γεωγραφικός εντοπισμός Constantinople, Istanbul 1. Introduction The Great Palace of the Byzantine Emperors in Constantinople was the ceremonial heart of the Byzantine Empire for a millennium, and occupied a site that is now recognized as a World Heritage precinct [Fig. 1].1 The Great Palace has a high cultural and historical significance, exerting a significant influence on both Western European and Levantine palatine architecture, and forming a link between Imperial Roman and medieval palaces. It is, nonetheless, only partially understood. Its remains are largely buried under later structures, notably the Sultan Ahmet Mosque, and can only be interpreted through texts and old representations. 2. The Upper Palace, including the Daphne Palace The oldest portion of the Great Palace, the Palace of Daphne, built by Constantine the Great and his successors in the 4th and 5th centuries, was a complex that is thought to have occupied the site upon which the Sultan Ahmet, or Blue, Mosque now stands. Its immediate context comprised: the Hippodrome and adjacent palaces; the Baths of Zeuxippos; the Imperial forum or Augustaion, where Justinian I erected his equestrian statue on a monumental column in the 6th century; the churches of St. -

Ward Et Al JRA 2017 Post-Print

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Ward, Kate, Crow, James and Crapper, Martin Water supply infrastructure of Byzantine Constantinople. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 30. pp. 175-195. ISSN 1047-7594 Published by: UNSPECIFIED URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://northumbria-test.eprints- hosting.org/id/eprint/49486/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/pol i cies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Citation: Ward, Kate, Crow, James and Crapper, Martin (2017) Water supply infrastructure of Byzantine Constantinople. Journal of Roman Archaeology. ISSN 1063-4304 (In Press) Published by: Journal of Roman Archaeology LLC URL: This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/31340/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. -

Arcadius 8; (Column

index INDEX 319 Arcadius 8; (column of) 184 Balat 213–14 Archaeological Museum 93ff Baldwin, Count of Flanders 15 Argonauts, myth of 259, 263, 276 Balıklı Kilisesi 197–98 Major references, in cases where many are listed, are given in bold. Numbers in italics Armenian, Armenians 25, 189, 192, Balkapanı Han 132 are picture references. 193, 241–42, 258, 278; (Cemetery) Baltalimanı 258 268; (Patriarchate) 192 Balyan family of architects 34, 161, 193; Arnavutköy 255 (burial place of) 268 A Alexander, emperor 67 Arsenal (see Tersane) Balyan, Karabet 34, 247 Abdülaziz, sultan 23, 72, 215, 251; Alexander the Great 7; (sculptures of) 96 Ashkenazi Synagogue 228 Balyan, Kirkor 34, 234 (burial place of) 117 Alexander Sarcophagus 94, 95 Astronomer, office of 42 Balyan, Nikoğos 34, 246, 247, 249, Abdülhamit I, sultan 23, 118; (burial Alexius I, emperor 13, 282 At Meydanı (see Hippodrome) 252, 255, 274, 275 place of) 43 Alexius II, emperor 14 Atatürk 24, 42, 146, 237, 248; Balyan, Sarkis 34, 83, 247, 258, 272, Abdülhamit II, sultan 23, 251, 252, Alexius III, emperor 14 (Cultural Centre) 242; (Museum) 243; 267 278; (burial place of) 117 Alexius IV, emperor 15 (statue of) 103 Bank, Ottoman 227 Abdülmecit I, sultan 71, 93, 161, 164, Alexius V, emperor 15 Atik Ali Pasha 171; (mosque of) 119 Barbarossa, pirate and admiral 152, 247; (burial place of) 162 Ali Pasha of Çorlu, külliye of 119–20 Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii 216 250, 250; (burial place of) 250; Abdülmecit II, last caliph 24 Ali Sufi, calligrapher 157, 158 Atik Sinan, architect 130, 155, 212; (ensign -

Costantino Da Bisanzio a Costantinopoli(*)1

EUGENIO RUSSO Costantino da Bisanzio a Costantinopoli(*)1 Abstract Constantine was a Christian. Of that there can be no doubt. The surviving signs of paganism visible in Constantine are rather the result of his education and culture. They in no way whatsoever constitute evidence for the continu- ing imperial worship of pagan divinities in the Constantinian period. Examination of the literary sources and ar- chaeological remains allows us to conclude that it is possible to recognize traces of the former Byzantium of Sep- timius Severus in the archaeological sites of the Strategion and a building beneath the Baths of Zeuxippos. In AD 324-330, the city on the Bosporus underwent a radical revolution: the city of Constantine went beyond the walls of the third century AD and it expanded to the west along the east-west axis. The previous city within the third- century walls was completely undermined in its north-south and east-west axes; there arose a new diagonal axis running northeast/southwest, which departed from the column of the Goths and arrived at the Augustaion, at the Hippodrome, and at the Palace (all Constantinian constructions, with St. Irene included). The centre of power (Palace-Hippodrome) was intimately linked to the Christian pole (St. Irene as the first cathedral and the pre- Justinianic St. Sophia that lay on the same axis and even closer to the Palace). According to the Chronicon Pas- chale, the church of St. Sophia was founded by Constantine in AD 326. The emperor deliberately abandoned the acropolis of Byzantium, and Byzantium was absorbed by the new city and obliterated by the new diagonal axis. -

Houses, Streets and Shops in Byzantine Constantinople from the fifth to the Twelfth Centuries K.R

Journal of Medieval History 30 (2004) 83–107 www.elsevier.com/locate/jmedhist Houses, streets and shops in Byzantine Constantinople from the fifth to the twelfth centuries K.R. Dark à Research Centre for Late Antique and Byzantine Studies, The University of Reading, Humanities and Social Sciences Building, Whiteknights, Reading RG6 6AA, UK Abstract This paper presents an analysis and reinterpretation of current evidence for houses, streets and shops in fifth- to twelfth-century Byzantine Constantinople, focussing on archaeological evidence. Previously unidentified townhouses and residential blocks are located. These show greater similarities to Roman-period domestic architecture than might be expected. Changes in the architectural style may be related to social change in the seventh century. Berger’s reconstruction of the early Byzantine street plan is shown to be archaeologically untenable. This has implications for the identification of formal planning and the boundaries of urban districts in the Byzantine capital. The limited archaeological evidence for streets and shops is also discussed. # 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Byzantine; Constantinople; Houses; Shops; Streets; Archaeology; Cultural change 1. Introduction This paper aims to ask what archaeology can tell us about the houses, streets and shops of Byzantine Constantinople between the fifth and 12th centuries. Abundant textual sources exist for the political, ecclesiastical and intellectual history of the city, but these provide much less information about the everyday life of its inhabitants. One would suppose that archaeology ought to play a central role in elucidating these aspects of urban history, but this has not been the à E-mail address: [email protected] (K.R. -

Water Supply Infrastructure of Byzantine Constantinople

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Ward, Kate, Crow, James and Crapper, Martin (2017) Water supply infrastructure of Byzantine Constantinople. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 30. pp. 175-195. ISSN 1063- 4304 Published by: Journal of Roman Archaeology URL: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759400074079 <https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759400074079> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/31340/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Water supply infrastructure of Byzantine Constantinople Kate Ward, James Crow and Martin Crapper1 Introduction Modern water supply systems – hidden beneath the ground, constructed, expanded, adapted and repaired intermittently by multiple groups of people – are often messy and difficult to comprehend. -

Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae

The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online Two Romes: Rome and Constantinople in Late Antiquity Lucy Grig and Gavin Kelly Print publication date: 2012 Print ISBN-13: 9780199739400 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2012 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199739400.001.0001 The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae John Matthews DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199739400.003.0004 Abstract and Keywords The first English translation of the Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, a crucial source for understanding the topography and urban development of early Constantinople, is presented here. This translation is accompanied, first, by an introduction to the text, and then by detailed discussion of the fourteen Regions, and finally by a conclusion, assessing the value of the evidence provided by this unique source. The discussion deals with a number of problems presented by the Notitia, including its discrepancies and omissions. The Notitia gives a vivid picture of the state of the city and its population just after its hundredth year: still showing many physical traces of old Byzantium, blessed with every civic amenity, but not particularly advanced in church building. The title Urbs Constantinopolitana nova Roma did not appear overstated at around the hundredth year since its foundation. Keywords: Byzantium, Constantinople, topography, Notitia, urban development, regions, Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae Page 1 of 50 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2017. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). -

Constantinople 527-1204 A.Dt.M

Hot Spots:TM CONSTANTINOPLE 527-1204 A.DT.M Written by MATT RIGGSBY Edited by NIKOLA VRTIS Cartography by MATT RIGGSBY An e23 Sourcebook for GURPS® STEVE JACKSON GAMES ® Stock #37-0661 Version 1.0 – August 2012 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . 3 Using GURPS LIFE OF THE MIND. 36 Matters of Language. 3 Mass Combat. 21 Education and Literature. 36 Publication History. 4 THE CHURCH . 21 The Price of Literature . 36 About the Author . 4 History . 21 Technology . 36 About GURPS . 4 Orthodox Practice. 22 Magic . 37 Controversy and Heresy. 23 Adventure Seed: 1. GEOGRAPHY . 5 Other Religions . 23 Walk Through the Fire . 37 BETWEEN MARMARA Non-Orthodox Characters . 23 SPECTACLES AND THE GOLDEN HORN . 5 Monasticism . 24 AND AMUSEMENTS. 38 THE CITY ITSELF . 6 Monk Characters . 24 The Arts . 38 The Landward View . 6 Relics . 24 Chariot Racing . 38 Population . 6 RANK, SPECTACLE, Re-Creating the Races . 38 Adventure Seed: AND CEREMONY. 25 Other Amusements . 38 Plugging the Holes . 7 Spare No Expense . 25 NOTABLE LOCATIONS . 39 The Seaward View . 7 Adventure Seed: The Wall. 39 The Inside View . 7 The Laundry Chase. 26 Hagia Sophia. 39 MAP OF CONSTANTINOPLE . 8 Help With Hierarchical Language Differences. 40 Classifications . 26 The Palace . 40 2. HISTORY . 9 10th-Century Title Table. 27 The Hippodrome. 40 FOUNDATION . 9 ECONOMY AND COMMERCE . 28 Basilica Cistern . 40 Constantinople (537 A.D.). 10 Prices . 28 GLORY AND COLLAPSE . 10 Money . 28 6. CAMPAIGNS. 41 Constantinople (750 A.D.). 11 Industry . 29 Constantinople as Home . 41 REVIVAL AND CRUSADES. 12 Weird Science and Industry . 29 Constantinople (1100 A.D.) . -

Byzantine” Crowns: Between East, West and the Ritual

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář dějin umění Bc. Teodora Georgievová “Byzantine” Crowns: between East, West and the Ritual Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Doc. Ivan Foletti, M.A. 2019 Prehlasujem, že som diplomovú prácu vypracovala samostatne s využitím uvedených prameňov a literatúry. Podpis autora práce First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor doc. Ivan Foletti for the time he spent proofreading this thesis, for his valuable advice and comments. Without his help, I would not be able to spend a semester at the University of Padova and use its libraries, which played a key role in my research. I also thank Valentina Cantone, who kindly took me in during my stay and allowed me to consult with her. I’m grateful to the head of the Department of Art History Radka Nokkala Miltová for the opportunity to extend the deadline and finish the thesis with less stress. My gratitude also goes to friends and colleagues for inspiring discussions, encouragement and unavailable study materials. Last but not least, I must thank my parents, sister and Jakub for their patience and psychological support. Without them it would not be possible to complete this work. Table of Contents: Introduction 6 What are Byzantium and Byzantine art 7 Status quaestionis 9 Coronation ritual 9 The votive crown of Leo VI 11 The Holy Crown of Hungary 13 The crown of Constantine IX Monomachos 15 The crown of Constance of Aragon 17 1. Byzantine crowns as objects 19 1.1 The votive crown of Leo VI 19 1.1.1 Crown of Leo VI: a votive offering? 19 1.1.2 Iconography and composition of the crown 20 1.1.3 Contacts between Venice and Constantinople, and the history of Leo VI’s crown 21 1.1.4 Role of the votive crowns in sacral space 23 . -

Byzantine Ports

BYZANTINE PORTS Central Greece as a link between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea Vol. I.: Text and Bibliography ALKIVIADIS GINALIS Merton College and Institute of Archaeology University of Oxford Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology Hilary Term 2014 This thesis was examined by Prof. Michael Vickers (Jesus College, Oxford) and Dr. Archie W. Dunn (Birmingham) on July 24, 2014 and was recommended for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology, which was officially granted to the author on October 21, 2014. Correspondence details of the author Dr. Alkiviadis Ginalis Feldgasse 3/11 1080, Vienna AUSTRIA Tel: 0043/6766881126 e-mail: [email protected] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a lot to the endless support and love of my family, who above all constantly kept encouraging me. I am particularly greatly indebted to my parents, Michalis and Monika, not only for making it financially possible but also for believing in me, and the way I chose to go. This gave me the incredible chance and strength to take the opportunity of getting the highest academic degree from one of the world’s best Universities. The 3 years I spent at Oxford, both inspired and enriched my academic knowledge, and became an unforgettable and unique personal experience of which I will profit my entire life. Furthermore, they gave me the necessary encouragement, as well as, made me think from different points of view. For support and thoughtful, as well as, dynamic and energetic guidance throughout my thesis my deepest debt is to my supervisors, Dr. Marlia Mango (St. -

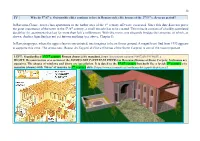

IV in Ravenna-Classe, Lower-Class Apartments in the Harbor Area of The

38 IV Why do 5th/6th c. Ostrogothic elites continue to live in Roman-style elite houses of the 2nd/3rd c. Severan period? In Ravenna-Classe, lower-class apartments in the harbor area of the 1st century AD were excavated. Since this date does not prove the great importance of the town in the 5th/6th century, a small miracle has to be created. This miracle consists of a boldly postulated durability for apartments that last for more than half a millennium. With this move, one elegantly bridges the centuries, of which, as shown, Andrea Agnellus has not yet known anything (see above, Chapter I). In Ravenna proper, where the upper class is concentrated, one imagines to be on firmer ground. A magnificent find from 1993 appears to supports this view. The aristocratic Domus dei Tappeti di Pietra (Domus of the Stone Carpets) is one of the most important LEFT: Standardized 1st/2nd century Roman domus (city mansion). [https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/91057223699970657/.] RIGHT: Reconstruction of a section of the DOMUS DEI TAPPETI DI PIETRA in Ravenna (Domus of Stone Carpets; bedrooms are upstairs). The shapes of windows and doors are speculation. It is dated to the 5th/6th century but built like a lavish 2nd century city mansion (domus) with 700 m2 of mosaics in 2nd century style. [https://www.ravennantica.it/en/domus-dei-tappeti-di-pietra-ra/.] 39 Italian archaeological sites discovered in recent decades. Located inside the eighteenth-century Church of Santa Eufemia, in a vast underground environment located about 3 meters below street level, it consists of 14 rooms paved with polychrome mosaics and marble belonging to a private building of the fifth-sixth century.