The Campaign to Save the London Trams 1946-1952

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4203 SLT Brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1

4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:08 Page 1 South London Trams Transport for Everyone The case for extensions to Tramlink 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 2 South London Trams Introduction South London Partnership Given the importance of good Tramlink is a highly successful integrated transport and the public transport system. It is is the strategic proven success of Tramlink reliable, frequent and fast, offers a partnership for south in the region, South London high degree of personal security, Partnership together with the is well used and highly regarded. London. It promotes London Borough of Lambeth has the interests of south established a dedicated lobby This document sets out the case group – South London Trams – for extensions to the tram London as a sub-region to promote extensions to the network in south London. in its own right and as a Tramlink network in south London, drawing on the major contributor to the widespread public and private development of London sector support for trams and as a world class city. extensions in south London. 4203 SLT brochure 6/21/04 19:09 Page 4 South London Trams Transport for Everyone No need for a ramp operated by the driver “Light rail delivers The introduction of Tramlink has The tram has also enabled Integration is key to Tramlink’s been hugely beneficial for its local previously isolated local residents success. Extending Tramlink fast, frequent and south London community. It serves to travel to jobs, training, leisure provides an opportunity for the reliable services and the whole of the community, with and cultural activities – giving wider south London community trams – unlike buses and trains – them a greater feeling of being to enjoy these benefits. -

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Greenwich Waterfront Transit

Greenwich Waterfront Transit Summary Report This report has been produced by TfL Integration Further copies may be obtained from: Tf L Integration, Windsor House, 42–50 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0TL Telephone 020 7941 4094 July 2001 GREENWICH WATERFRONT TRANSIT • SUMMARY REPORT Foreword In 1997, following a series of strategic studies into the potential for intermediate modes in different parts of outer London, London Transport (LT) commenced a detailed assessment under the title “Greenwich Waterfront Transit” of a potential scheme along the south bank of the Thames between Greenwich Town Centre and Thamesmead then on to Abbey Wood. In July 2000, LT’s planning functions were incorporated into Transport for London (TfL). A major factor in deciding to carry out a detailed feasibility study for Waterfront Transit has been the commitment shown by Greenwich and Bexley Councils to assist in the development of the project and their willingness to consider the principle of road space re-allocation in favour of public transport. This support, as well as that of other bodies such as SELTRANS, Greenwich Development Agency,Woolwich Development Agency and the Thames Gateway London Partnership, is acknowledged by TfL. The ongoing support of these bodies will be crucial if the proposals are to proceed. A major objective of this exercise has been to identify the traffic management measures required to achieve segregation and high priority over other traffic to encourage modal shift towards public transport, particularly from the private car. It is TfL’s view,supported by the studies undertaken, that the securing of this segregation and priority would be critical in determining the success of Waterfront Transit. -

Informing You Every Stop of the Way

London Buses iBus Informing you every stop of the way MAYOR OF LONDON Transport for London London Buses London Buses informing you every stop of the way The most important priority for London Buses is to provide the best possible bus service for its 6.3 million daily bus passengers. By introducing a £117m state-of-the-art Automatic Vehicle Location (AVL) technology system and comprehensive telecommunications across London, millions of bus passengers are soon to benefit from a more reliable, consistent bus service and will have access to real time passenger information (RTPI) at bus stops, on board buses and from SMS text messaging. With an 8000-strong and increasing bus fleet, Try the new bus travelling London Buses’ existing radio communications experience systems can no longer cope. iBus - one of the largest projects of its kind in the world - will Imagine having real time bus service revolutionise how services are delivered and information at your fingertips. A typical monitored. bus journey could be like this: A wealth of journey time data will be available You receive an up to the minute SMS text to analyse and improve on, and three of the message on your mobile as you walk out of same number buses arriving at once at a bus your house. As you arrive at the bus stop you stop will be a thing of the past, as every bus can confirm on the Countdown display that will be tracked and monitored ensuring an your bus will arrive in an accurately predicted efficient service on all routes. -

GTR Passengers’ Awareness of the Timetable Change

Office of Rail and Road Rail investigation report: Govia Thameslink Railway: Provision of passenger information – May 2018 timetable change Published March 2019 Contents Executive Summary 4 Our findings – pre-20 May ........................................................................................... 4 Our findings – post-20 May ......................................................................................... 5 Next steps ................................................................................................................... 8 1. Background 9 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 9 ORR Inquiry into the timetable disruption in May 2018 ............................................... 9 Enforcement remit ..................................................................................................... 10 Condition 4 of the train operators’ licence SNRP ...................................................... 10 Regulatory context .................................................................................................... 11 Conduct of the investigation ...................................................................................... 13 Structure of this document ........................................................................................ 14 2. Passenger experience and impact 15 Introduction ............................................................................................................... -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Public Transport Liaison Panel, 16

Public Document Pack Public Transport Liaison Panel To: Councillor Muhammad Ali (Chair) Councillor Nina Degrads (Vice-Chair) Councillors Ian Parker A meeting of the Public Transport Liaison Panel will be held on Tuesday, 16 October 2018 at 2.00 pm in Council, Chamber - Town Hall JACQUELINE HARRIS-BAKER Thomas Downs Director of Law and Monitoring Officer 02087266000 x86166 London Borough of Croydon 020 8726 6000 Bernard Weatherill House [email protected] 8 Mint Walk, Croydon CR0 1EA www.croydon.gov.uk/meetings AGENDA Item No. Item Title Report Page nos. 1. Introductions To invite all attendees to introduce themselves. 2. Apologies for absence To receive any apologies for absence from any members of the Committee. 3. Disclosures of interests In accordance with the Council’s Code of Conduct and the statutory provisions of the Localism Act, Members and co-opted Members of the Council are reminded that it is a requirement to register disclosable pecuniary interests (DPIs) and gifts and hospitality to the value of which exceeds £50 or multiple gifts and/or instances of hospitality with a cumulative value of £50 or more when received from a single donor within a rolling twelve month period. In addition, Members and co-opted Members are reminded that unless their disclosable pecuniary interest is registered on the register of interests or is the subject of a pending notification to the Monitoring Officer, they are required to disclose those disclosable pecuniary interests at the meeting. This should be done by completing the Disclosure of Interest form and handing it to the Democratic Services representative at the start of the meeting. -

Transport with So Many Ways to Get to and Around London, Doing Business Here Has Never Been Easier

Transport With so many ways to get to and around London, doing business here has never been easier First Capital Connect runs up to four trains an hour to Blackfriars/London Bridge. Fares from £8.90 single; journey time 35 mins. firstcapitalconnect.co.uk To London by coach There is an hourly coach service to Victoria Coach Station run by National Express Airport. Fares from £7.30 single; journey time 1 hour 20 mins. nationalexpress.com London Heathrow Airport T: +44 (0)844 335 1801 baa.com To London by Tube The Piccadilly line connects all five terminals with central London. Fares from £4 single (from £2.20 with an Oyster card); journey time about an hour. tfl.gov.uk/tube To London by rail The Heathrow Express runs four non- Greater London & airport locations stop trains an hour to and from London Paddington station. Fares from £16.50 single; journey time 15-20 mins. Transport for London (TfL) Travelcards are not valid This section details the various types Getting here on this service. of transport available in London, providing heathrowexpress.com information on how to get to the city On arrival from the airports, and how to get around Heathrow Connect runs between once in town. There are also listings for London City Airport Heathrow and Paddington via five stations transport companies, whether travelling T: +44 (0)20 7646 0088 in west London. Fares from £7.40 single. by road, rail, river, or even by bike or on londoncityairport.com Trains run every 30 mins; journey time foot. See the Transport & Sightseeing around 25 mins. -

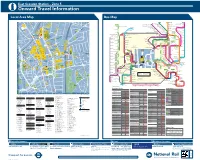

Local Area Map Bus Map

East Croydon Station – Zone 5 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map FREEMASONS 1 1 2 D PLACE Barrington Lodge 1 197 Lower Sydenham 2 194 119 367 LOWER ADDISCOMBE ROAD Nursing Home7 10 152 LENNARD ROAD A O N E Bell Green/Sainsbury’s N T C L O S 1 PA CHATFIELD ROAD 56 O 5 Peckham Bus Station Bromley North 54 Church of 17 2 BRI 35 DG Croydon R E the Nazarene ROW 2 1 410 Health Services PLACE Peckham Rye Lower Sydenham 2 43 LAMBERT’S Tramlink 3 D BROMLEY Bromley 33 90 Bell Green R O A St. Mary’s Catholic 6 Crystal Palace D A CRYSTAL Dulwich Library Town Hall Lidl High School O A L P H A R O A D Tramlink 4 R Parade MONTAGUE S S SYDENHAM ROAD O R 60 Wimbledon L 2 C Horniman Museum 51 46 Bromley O E D 64 Crystal Palace R O A W I N D N P 159 PALACE L SYDENHAM Scotts Lane South N R A C E WIMBLEDON U for National Sports Centre B 5 17 O D W Forest Hill Shortlands Grove TAVISTOCK ROAD ChCCheherherryerryrry Orchard Road D O A 3 Thornton Heath O St. Mary’s Maberley Road Sydenham R PARSON’S MEAD St. Mary’s RC 58 N W E L L E S L E Y LESLIE GROVE Catholic Church 69 High Street Sydenham Shortlands D interchange GROVE Newlands Park L Junior School LI E Harris City Academy 43 E LES 135 R I Croydon Kirkdale Bromley Road F 2 Montessori Dundonald Road 198 20 K O 7 Land Registry Office A Day Nursery Oakwood Avenue PLACE O 22 Sylvan Road 134 Lawrie Park Road A Trafalgar House Hayes Lane G R O V E Cantley Gardens D S Penge East Beckenham West Croydon 81 Thornton Heath JACKSON’ 131 PLACE L E S L I E O A D Methodist Church 1 D R Penge West W 120 K 13 St. -

Ultimate Spectators Guide to the London Marathon

ULTIMATE SPECTATORS GUIDE TO THE LONDON MARATHON We recommend you purchase a Travelcard to travel around London on the day as this will allow access to Rail, Tube and Bus at no extra charge. Zones 1-2 should be adequate for the travelling around the route, however if you need to go further afield, please check which zones you’ll be travelling in. Buses no longer accept cash payments. You’ll need to use a Travelcard, Oyster card or pay with a contactless debit/credit card. Please note that whilst we do have cheering stations at Tower Bridge (mile 12) and along the Victoria Embankment (mile 24) these will be manned by volunteers and we do not recommend you go to those points on race day. This is because these areas are extremely busy and it can take a long time to move through the crowds. By skipping Tower Bridge, you have more chance of seeing your runner at multiple points on the route, and by going straight to mile 25 from 19 you’ll cheer them on from the end! START AREA Although it’s advised not to accompany your runner to the start due to the high volumes of people, if you decide to see them off, please be aware that spectators will not be allowed into the assembly areas of the start. Once you’ve said your farewells and good lucks, head down the Avenue out of Greenwich Park. Once out of the park, turn left onto Nevada Street and keep walking as it turns into Burney Street. -

Reinohl Collection Album List

Reinohl Collection album list The Reinohl Collection consists of 180 albums compiled by two brothers, Herbert and Albert Reinohl. The brothers were born in the late nineteenth century and began collecting material about transport (buses in particular) from childhood, continuing through to the 1950s. The collection is principally made up of tickets, but it also includes illustrations, press cuttings, journal articles and other ephemera from the UK and around the world. The list below gives brief details of what is covered by each album. If you would like to enquire about specific contents in the albums please contact us. The collection forms part of the Library collection at London Transport Museum (LTM) and is stored at the Museum Depot at Acton. Visits are available monthly, please check our website for further information https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/research/library. For all appointments, or any queries, please contact us. London Transport Museum Library Albany House, 98 Petty France, London SW1H 9EA Tel: +44 (0)343 222 5000 and select option 3 Email: [email protected] October 2019 1 Abbreviations used in the list: LGOC London General Omnibus Company LCC London County Council LPTB London Passenger Transport Board LT London Transport UDC Urban District Council Album Description 1 1829 London's First Omnibus to 1968 Woodruff's Omnibuses 2 Unknown Proprietors to James Powell 3 London & Suburban Omnibus Company to LGOC Route 14A 4 LGOC & Associate Companies Route 15 to LGOC & Thomas Tilling Ltd. Route 33A 5 LGOC & Thomas -

Rail Accident Report

Rail Accident Report Fatal accident at Morden Hall Park footpath crossing 13 September 2008 Report 06/2009 March 2009 This investigation was carried out in accordance with: l the Railway Safety Directive 2004/49/EC; l the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003; and l the Railways (Accident Investigation and Reporting) Regulations 2005. © Crown copyright 2009 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This document/publication is also available at www.raib.gov.uk. Any enquiries about this publication should be sent to: RAIB Email: [email protected] The Wharf Telephone: 01332 253300 Stores Road Fax: 01332 253301 Derby UK Website: www.raib.gov.uk DE21 4BA This report is published by the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, Department for Transport. Fatal accident at Morden Hall Park footpath crossing, 13 September 2008 Contents Introduction 5 Preface 5 Key definitions 5 The Accident 6 Summary of the accident 6 The parties involved 6 Location 7 External circumstances 11 The tram 11 The accident 11 Consequences of the accident 11 Events following the accident 12 The Investigation 13 Investigation process and sources of evidence 13 Key Information 14 Previous -

Places to See and Visit

Places to See and Visit When first prepared in 1995 I had prepared these notes for our cottages one mile down the road near Biggin Dale with the intention of providing information regarding local walks and cycle rides but has now expanded into advising as to my personal view of places to observe or visit, most of the places mentioned being within a 25 minutes drive. Just up the road is Heathcote Mere, at which it is well worth stopping briefly as you drive past. Turn right as you come out of the cottage, right up the steep hill, go past the Youth Hostel and it is at the cross-road. In summer people often stop to have picnics here and it is quite colourful in the months of June and July This Mere has existed since at least 1462. For many of the years since 1995, there have been pairs of coots living in the mere's vicinity. If you turn right at the cross roads and Mere, you are heading to Biggin, but after only a few hundred yards where the roads is at its lowest point you pass the entrance gate to the NT nature reserve known as Biggin Dale. On the picture of this dale you will see Cotterill Farm where we lived for 22 years until 2016. The walk through this dale, which is a nature reserve, heads after a 25/30 minute walk to the River Dove (There is also a right turn after 10 minutes to proceed along a bridleway initially – past a wonderful hipped roofed barn, i.e with a roof vaguely pyramid shaped - and then the quietest possible county lane back to Hartington).