Crime on Public Transport March 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Operator's Story Appendix

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: London’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London Community of Metros CoMET The Operator’s Story: Notes from London Case Study Interviews February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in London. These notes are based upon 14 meetings between 6th-9th October 2015, plus one further meeting in January 2016. This document will ultimately form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’ piece Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and TfL. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by TfL (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by TfL themselves and those expressed about their organisation. -

Bus and Rail Guide

FREQUENCY GUIDE FREQUENCY (MINUTES) Chatham Town Centre Gillingham Town Centre Monday – Friday Saturday Sunday Operator where to board your bus where to board your bus Service Route Daytime Evening Daytime Evening Daytime Evening 1 M Chatham - Chatham Maritime - Dockside Outlet Centre - Universities at Medway Campus 20 minutes - 20 minutes - hourly - AR Destination Service Number Bus Stop (- Gillingham ASDA) - Liberty Quays - The Strand (- Riverside Country Park (Suns)) Fort Amherst d t . i a e Hempstead Valley 116 E J T o e t Coouncil Offices r . R t e Trinity Road S d R e 2 S M Chatham - Chatham Maritime - Dockside Outlet Centre 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes 20 minutes AR m Medway r u ll t Liberty Quays 176 177 (Eves/Sun) D H D o PUBLIC x rt Y i S ha Park o O K M A CAR F n t 6*-11* Grain - Lower Stoke - Allhallows - High Halstow - Hoo - Hundred of Hoo Academy school - - - - - AR 16 e C C e PPARKARK d ro Lower Halstow 326 327 E J e s W W r s Chathamtham Library K i r T Bus and rail guide A t A E S 15 D T S R C tr E E e t 100 M St Mary’s Island - Chatham Maritime - Chatham Rail Station (see also 1/2 and 151) hourly - hourly - - - AR and Community Hub E e t O 19 R E Lower Rainham 131* A J T F r R e A R F e T e E . r D M T n S t Crown St. -

Informing You Every Stop of the Way

London Buses iBus Informing you every stop of the way MAYOR OF LONDON Transport for London London Buses London Buses informing you every stop of the way The most important priority for London Buses is to provide the best possible bus service for its 6.3 million daily bus passengers. By introducing a £117m state-of-the-art Automatic Vehicle Location (AVL) technology system and comprehensive telecommunications across London, millions of bus passengers are soon to benefit from a more reliable, consistent bus service and will have access to real time passenger information (RTPI) at bus stops, on board buses and from SMS text messaging. With an 8000-strong and increasing bus fleet, Try the new bus travelling London Buses’ existing radio communications experience systems can no longer cope. iBus - one of the largest projects of its kind in the world - will Imagine having real time bus service revolutionise how services are delivered and information at your fingertips. A typical monitored. bus journey could be like this: A wealth of journey time data will be available You receive an up to the minute SMS text to analyse and improve on, and three of the message on your mobile as you walk out of same number buses arriving at once at a bus your house. As you arrive at the bus stop you stop will be a thing of the past, as every bus can confirm on the Countdown display that will be tracked and monitored ensuring an your bus will arrive in an accurately predicted efficient service on all routes. -

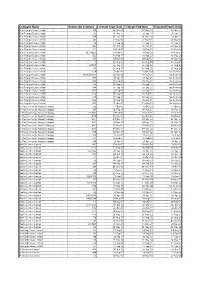

Operators Route Contracts

Company Name Routes On Contract Contract Start Date Contract End Date Extended Expiry Date Blue Triangle Buses Limited 300 06-Mar-10 07-Dec-18 03-Mar-17 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 193 01-Oct-11 28-Sep-18 28-Sep-18 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 364 01-Nov-14 01-Nov-19 29-Oct-21 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 147 07-May-16 07-May-21 05-May-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 376 17-Sep-16 17-Sep-21 15-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 346 01-Oct-16 01-Oct-21 29-Sep-23 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL3 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL1/NEL1 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited EL2 18-Feb-17 18-Feb-22 16-Feb-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 101 04-Mar-17 04-Mar-22 01-Mar-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 5 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 15/N15 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 115 26-Aug-17 26-Aug-22 23-Aug-24 Blue Triangle Buses Limited 674 17-Oct-15 16-Oct-20 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 649/650/651 02-Jan-16 01-Jan-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 687 30-Apr-16 30-Apr-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 608 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 646 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 648 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 652 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 656 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 679 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote Blue Triangle Buses Limited 686 03-Sep-16 03-Sep-21 See footnote -

Policing the Bridges Appendix 1.Pdf

Appendix One NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Policing the Bridges and allocation of costs to the Bridge House Estates OPINION Introduction 1. This Opinion considers the nature and extent of the City's obligations as to the policing of the City's bridges and the extent to which those costs may be attributed to the Bridge House Estates. It focuses on general policing responsibilities rather than any specific project, although the issue has recently received renewed attention as the result of a project to install river cameras at the bridges. Issues concerning the quantum of any contribution and a Trustee‟s general duty to act in the best interests of Trust are not dealt with in this Opinion. 2. In order to provide context and to inform interpretation, some historical constitutional background is included. This has however been confined to material which assists in deciding the extent of the obligations and sources of funding rather than providing a broader narrative. After a short account of the history of the „Watch‟, each bridge is considered in turn, concluding, in each case, with an assessment of the position under current legislation. Establishment of Watches and the Bridges 3. In what appears to be a remarkably coordinated national move, the Statute of Winchester 1285 (13 Edw. I), commanded that watch be kept in all cities and towns and that two Constables be chosen in every "Hundred" or "Franchise"; specific to the City, the Statuta Civitatis London, also passed in 1285, regularised watch arrangements so that the gates of London would be shut every night and that the City‟s twenty-four Wards, would each have six watchmen controlled by an Alderman. -

The Go-Ahead Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2019 1 Stable Cash Generative

Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 29 June 2019 Taking care of every journey Taking care of every journey Regional bus Regional bus market share (%) We run fully owned commercial bus businesses through our eight bus operations in the UK. Our 8,550 people and 3,055 buses provide Stagecoach: 26% excellent services for our customers in towns and cities on the south FirstGroup: 21% coast of England, in north east England, East Yorkshire and East Anglia Arriva: 14% as well as in vibrant cities like Brighton, Oxford and Manchester. Go-Ahead’s bus customers are the most satisfied in the UK; recently Go-Ahead: 11% achieving our highest customer satisfaction score of 92%. One of our National Express: 7% key strengths in this market is our devolved operating model through Others: 21% which our experienced management teams deliver customer focused strategies in their local areas. We are proud of the role we play in improving the health and wellbeing of our communities through reducing carbon 2621+14+11+7+21L emissions with cleaner buses and taking cars off the road. London & International bus London bus market share (%) In London, we operate tendered bus contracts for Transport for London (TfL), running around 157 routes out of 16 depots. TfL specify the routes Go-Ahead: 23% and service frequency with the Mayor of London setting fares. Contracts Metroline: 18% are tendered for five years with a possible two year extension, based on Arriva: 18% performance against punctuality targets. In addition to earning revenue Stagecoach: 13% for the mileage we operate, we have the opportunity to earn Quality Incentive Contract bonuses if we meet these targets. -

City of London Police National Fraud Intelligence Bureau

1 CITY OF LONDON POLICE: OFFICIAL - RECIPIENT ONLY City of London Police National Fraud Intelligence Bureau Coronavirus fraud core script – updated 28 May 2020 (Update 5) This script has been approved by the National Economic Crime Centre, Home Office and National Cyber Security Centre. Page 2 – Key messages and protection advice Page 4 – Agreed lines on specific issues Page 10 – Latest update from NFIB CITY OF LONDON POLICE: OFFICIAL - RECIPIENT ONLY 2 CITY OF LONDON POLICE: OFFICIAL - RECIPIENT ONLY Key messages 1) Criminals will use every opportunity they can to defraud innocent people. They will continue to exploit every angle of this national crisis and we want people to be prepared. 2) We are not trying to scare people at a time when they are already anxious. We simply want people to be aware of the very simple steps they can take to protect themselves from handing over their money, or personal details, to criminals. 3) Law enforcement, government and industry are working together to protect people, raise awareness, take down fraudulent websites and email addresses, and ultimately bring those responsible to justice. 4) If you think you’ve fallen for a scam, contact your bank immediately and report it to Action Fraud on 0300 123 2040 or via actionfraud.police.uk. If you are in Scotland, please report to Police Scotland directly by calling 101. 5) You can report suspicious texts by forwarding the original message to 7726, which spells SPAM on your keypad. You can report suspicious emails by forwarding the original message to [email protected]. -

62 Autumn 2012.Qxp

Issue 62 Autumn 2012 Price £3 newsforum The London Forum - working to protect and improve the quality of life in London The London Forum of Amenity and Civic Societies Founded 1988 w www.londonforum.org.uk In this issue 1 Is the BBC impartial? 9 Outsourcing public sector development 2 London Forum AGM services 16 News from the Mayor and GLA Spotlight on 4 London Forum Survey 2012 10 Spotlight on Hammersmith 17 Update on Thames Tunnel project 5 London Forum responses Society 18 Round the Societies Hammersmith 6 Volunteering at the Olympics 12 Airports Update 19 News briefs 8 A round up of recent legislative 13 Transport matters 20 Events and meetings Society Page 10 matters 14 Heritage, planning and A matter of public concern Is the BBC impartial? Heathrow third runway was championed by a supposedly “impartial” BBC interviewer when interviewing London’s Mayor on the newly established Commission on Aviation Capacity. Newsforum editor Helen Marcus found the BBC complaints procedure a barrier to communication. n November 2nd 2012 Radio 4’s complain. However when I tried to find a Today Programme ran an item on Evan Davis sounded as phone number or email address to contact on Othe announcement of the Davies the BBC website complaints page, it seemed Commission on aviation capacity. Evan Davis though he was a lobbyist for designed to be a barrier to prevent people interviewed three people. He first spoke to from complaining or contacting the BBC at all. MP Julian Huppert, who said that we should the Heathrow 3rd runway The complaints web-page is circular – you make better use of existing infrastructure, and Johnson quite need to be tech-savvy to decipher it. -

Cutting Carbon from the London Bus Fleet

Cutting Carbon from the London Bus Fleet Finn Coyle Environmental Managg(er (Trans port Emissions) TfL Presentation Overview • Environmental Priorities • EiEnvironmen tlItal Impac tfthTfLBFltt of the TfL Bus Fleet • Initiatives to date • Short / Medium term Environmental Strategy • Long Term Environmental Strategy Environmental priorities • Climate Change • Mayor’ s Climate Change Action Plan sets target of 60% CO2 reduction across London by 2025 • Air Quality • EU Limit Values for – Fine particles (PM10) – Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) Calculating the Environmental Impact of the Bus Fleet • TfL developed with Millbrook a ‘real world’ drive cycle based on Route 159 from Brixton to Oxford Street • Every new type of bus is tested to ensure CO2, PM and NOx emissions meet TfL’s requirements • Enables TfL to model the impact of the Bus Fleet on London emissions and predict the impact of interventions 60.00 50.00 40.00 ) 30.00/h mm k ( 20.00eed p S 10.00 0.00 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 1800 2000 2200 Test Time (secs) CO2 impact of the bus fleet • 6% of London’s transport CO2 emissions come from buses • Buses are largest contributor to TfL’s CO2 footprint accounting for 31% of emissions • Network consumes 250 million litres of diesel per year • 650,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions produced per annum Millions of Passengers per Day 2008/09 New York Buses (Greater) Paris Buses London/South‐East Trains London Underground London Buses 01234567 Air Quality impact of the bus fleet • Link between air quality and cardio-respiratory health is clear • Air -

Keeping Successful Global Cities on the Move Mass Transit 2 Mass Transit 3

KEEPING SUCCESSFUL GLOBAL CITIES ON THE MOVE MASS TRANSIT 2 MASS TRANSIT 3 KEEPING CITIES A WORLD LEADER ON THE MOVE IN MASS TRANSIT SNCF and Keolis are among the world’s largest mass transit operators. Our global businesses include rail, metro, tram and bus rapid transit BILLION PEOPLE services in 11 cities with populations of over Over 6 living in cities by 2045, one million people. up from c.4 billion today* Across the world, we have won a reputation for working constructively with public transport authorities (PTAs) to respond to the challenge SNCF: of rapidly rising patronage driven by economic MILLION PASSENGERS growth and migration to urban areas. As cities carried every day continue to become more prosperous and 3.2 densely populated, high frequency, integrated CONTENTS in Greater Paris mass transit will be increasingly important as the only means of meeting demand for travel 4. Serving cities on four continents Keolis: in a safe, convenient and sustainable manner. MILLION PASSENGERS Drawing on decades of experience, we are 6. Our world-leading networks, services at the forefront of developing new and existing and knowledge 6 every day worldwide transport networks to meet the needs of global 8. Our promises to clients, passengers cities now and in the future. and communities * United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 10. Pillar 1: Securing successful takeovers Population Division (2014) 12. Pillar 2: Optimising operational performance 14. Pillar 3: Thinking Like a Passenger 16. Pillar 4: Enhancing network capability SNCF operates rail services Keolis, in which SNCF has 18. Pillar 5: Helping to fulfil cities’ ambitions throughout France, including a 70% shareholding, designs high density urban lines in Greater and operates networks combining 20. -

Travel in London, Report 3 I

Transport for London Transport for London for Transport Travel in London Report 3 Travel in London Report 3 MAYOR OF LONDON Transport for London ©Transport for London 2010 All rights reserved. Reproduction permitted for research, private study and internal circulation within an organisation. Extracts may be reproduced provided the source is acknowledged. Disclaimer This publication is intended to provide accurate information. However, TfL and the authors accept no liability or responsibility for any errors or omissions or for any damage or loss arising from use of the information provided. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................ 27 1.1 Travel in London report 3 ............................................................................ 27 1.2 The Mayor of London’s transport strategy .................................................. 27 1.3 The monitoring regime for the Mayor’s Transport Strategy ......................... 28 1.4 The MTS Strategic Outcome Indicators ....................................................... 28 1.5 Treatment of MTS Strategic Outcome Indicators in this report ................... 31 1.6 Relationship to other Transport for London (TfL) and Greater London Authority (GLA) Group publications ............................................................ 32 1.7 Contents of this report .............................................................................. -

City of London Policing Plan

City of London Police Policing Plan 2020-23 2020 - CITY OF LONDON POLICING 2023 PLAN Supporting the Police Code of Ethics by policing with professionalism, fairness and integrity City of London Police Policing Plan 2020-23 Foreword from the Commissioner and Chairman of the Police Authority Board I am pleased to present to you our plan for policing the City of London Together, the Police Authority and the City of London Police have over the next 3 years. developed priorities that reflect the policing and crime issues that you told us are important to you, that respond to the current threats and also Policing has faced many difficult challenges over recent years, which has deliver on our commitment as national lead force to tackle economic included delivering services with fewer officers and significant constraints crime and fraud. on budgets. I am pleased to report that this Plan presents for the first time since 2011 a significant increase in the number of officers for the City of Whilst, the City of London remains one of the safest places to live, the London, which will enhance our ability to meet those challenges head on. challenges of persistent crime along with new and emerging crime threats Today, there is no greater challenge than the threat we face from are always present and the Police Authority is determined to ensure that terrorism and increasing levels of violent crime. My primary aim is to we have a service that continues to make the City safe and secure. The protect the people and infrastructure of the City of London, ensuring the recent increase in funding for police officers is a major boost in enabling Square Mile remains a safe and vibrant place to live, work and visit.