Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex Draft Conservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultrasociality: When Institutions Make a Difference

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304625948 Ultrasociality: When institutions make a difference Article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences · June 2016 DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X15001089 CITATIONS READS 0 5 3 authors, including: Petr Houdek Julie Novakova Vysoká škola ekonomická v Praze Charles University in Prague 11 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS 6 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Petr Houdek Retrieved on: 20 September 2016 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2016), Page 1 of 60 doi:10.1017/S0140525X1500059X, e92 The economic origins of ultrasociality John Gowdy Department of Economics and Department of Science and Technology Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 12180 [email protected] http://www.economics.rpi.edu/pl/people/john-gowdy Lisi Krall Department of Economics, State University of New York (SUNY) at Cortland, Cortland, NY 13045 [email protected] Abstract: Ultrasociality refers to the social organization of a few species, including humans and some social insects, having a complex division of labor, city-states, and an almost exclusive dependence on agriculture for subsistence. We argue that the driving forces in the evolution of these ultrasocial societies were economic. With the agricultural transition, species could directly produce their own food and this was such a competitive advantage that those species now dominate the planet. Once underway, this transition was propelled by the selection of within-species groups that could best capture the advantages of (1) actively managing the inputs to food production, (2) a more complex division of labor, and (3) increasing returns to larger scale and larger group size. -

Quantitative Appraisal of Non-Irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program 10-22-2018 Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Agribusiness Commons, Agricultural Economics Commons, Agricultural Science Commons, Applied Mathematics Commons, Applied Statistics Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Riggs, Shelby, "Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 117. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/117 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Ag Land in South Dakota An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska – Lincoln By Shelby Riggs, BS Agricultural Economics College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources October 22nd, 2018 Faculty Mentor: Jeffrey Stokes, PhD, Agricultural Economics Abstract This appraisal attempts to remove subjectivity from the appraisal process and replace it with quantitative analysis of known data to generate fair market value the subject property. Two methods of appraisal will be used, the income approach and the sales comparison approach. For the income approach, I use the average cash rent for the region, the current property taxes for the subject property, and a capitalization rate based on Stokes’ (2018) capitalization rate formula to arrive at my income-based valuation. -

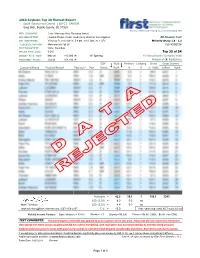

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report Top 30 of 54

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report South Dakota East Central [ SDEC ] CAVOUR Greg Bich, Beadle County, SD 57324 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC, New Richland, MN PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Harness Xtra, Roundup (twice) SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non-irrigated All-Season Test SOIL CONDITIONS: Very low P, very high K, 5.9 pH, 3.0% OM, 20.1 CEC Maturity Group 1.6 - 2.3 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Minimum w/o fall till S2018SDEC06 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup APPLIED N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 Top 30 of 54 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: May 26 140,000 /A 30" Spacing For Gross Income (Sorted by Yield) HARVESTED - STAND: Oct 23 108,100 /A Average of (2) Replications SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand†Technol.† Mat. Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank Averages = 42.8 10.1 1 108.1 $343 LSD (0.10) = 8.3 0.5 ns Mark Tollefson LSD (0.25) = 4.4 0.3 ns [email protected], (507) 456-2357 C.V. = 15.0 Prev. years avg. yield, 45.7 bu/a, 10 yrs Yield & Income Factors: Base Moisture = 13.0% Shrink = 1.3 Drying = $0.020 Prices = $8.00 GMO; $8.00 non-GMO TEST COMMENTS: The preemergence herbicide was applied to only a portion of the test area. Areas that did not receive this treatment were weedy the entire season as glphosate did not control everything. One replication was not harvested due to extreme weed pressure. Soybean yield was great in areas with good weed control (1 replication) but dropped considerably elsewhere. -

Selected Qualitative Parameters Above-Ground Phytomass of the Lenor-First Slovak Cultivar of Festulolium A

Acta fytotechn zootechn, 22, 2019(1): 13–16 http://www.acta.fapz.uniag.sk Original Paper Selected qualitative parameters above-ground phytomass of the Lenor-first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A. et Gr. Peter Hric*, Ľuboš Vozár, Peter Kovár Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic Article Details: Received: 2018-10-04 | Accepted: 2018-11-06 | Available online: 2019-01-31 https://doi.org/10.15414/afz.2019.22.01.13-16 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License The aim of this experiment was to compare selected qualitative parameters in above-ground phytomass of the first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A et. Gr. cv. Lenor in comparison to earlier registered cultivars Felina and Hykor. The pot experiment was conducted at the Demonstrating and Research base of the Department of Grassland Ecosystems and Forage Crops, Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra (Slovak Republic) with controlled moisture conditions (shelter) in 2017. Content of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, crude fibre and water soluble carbohydrates were determined from dry above-ground phytomass of grasses. The significantly highest (P <0.05) nitrogen content in average of cuts was in above-ground phytomass of Felina (30.3 g kg-1) compared to Hykor (25.4 g kg-1) and new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (25.0 g kg-1). The lowest phosphorus content was found out in hybrid Lenor (3.4 g kg-1). In average of three cuts, the lowest concentration of potassium was in new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (5.8 g kg-1). The lowest content of calcium was found out in hybrid Lenor (7.0 g kg-1). -

A Preliminary Survey of the Bird Life of North Dakota

UNIVERSITY OP MICHIGAN MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY Miscellaneous Publications No. 10 A Preliminary Survey of the Bird Life of North Dakota BY NORMAN A. WOOD ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY JULY 2, 1923 OUTLINE MAP OF NORTH DAKOTA UNIVERSI'rY OF hlICHIGAN MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY Miscellaneous Publications No. 10 A Preliminary Survey of the Bird Life of North Dakota RY NORMAN A. WOOD ANN ARBOR, MICIIIGAN PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY JULY 2, I923 The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigart, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous PubK- cations. Both series were founded bv Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradsl~aw I-I. Swales and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, j-rve as a medium for the publication of brief oriqinal papers based principally upon the collections in the Museum. The papers are issued separately to libraries and specialists, and, when a sufficient nu~uberof pages have l~crn printed to make a volume, a title page, index, and table of contents are sup- plied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the entire series. The Miscellaneous Publications include papers on field and museum technique, monographic studies and other papers not within the scope of the Occasional Papers. The papers are published separately, and, as it is not intended that they shall be grouped into volumes, each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. ALEXANDERG. RUTHITEN, Director of the Museum of Zoology, [Jniversity ~f Michigan. A PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF THE BIRD LIFE OF NORTH DAKOTA The field studies upon which this paper is largely based were carried on during the summers of 1920 and 1921. -

GEOLOGY and GROUND WATER RESOURCE S of Stutsman County, North Dakota

North Dakota Geological Survey WILSON M. LAIRD, State Geologis t BULLETIN 41 North Dakota State Water Conservation Commission MILO W . HOISVEEN, State Engineer COUNTY GROUND WATER STUDIES 2 GEOLOGY AND GROUND WATER RESOURCE S of Stutsman County, North Dakota Part I - GEOLOG Y By HAROLD A. WINTERS GRAND FORKS, NORTH DAKOTA 1963 This is one of a series of county reports which wil l be published cooperatively by the North Dakota Geological Survey and the North Dakota State Water Conservation Commission in three parts . Part I is concerned with geology, Part II, basic data which includes information on existing well s and test drilling, and Part III which will be a study of hydrology in the county . Parts II and III will be published later and will be distributed a s soon as possible . CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Acknowledgments 3 Previous work 5 GEOGRAPHY 5 Topography and drainage 5 Climate 7 Soils and vegetation 9 SUMMARY OF THE PRE-PLEISTOCENE STRATIGRAPHY 9 Precambrian 1 1 Paleozoic 1 1 Mesozoic 1 1 PREGLACIAL SURFICIAL GEOLOGY 12 Niobrara Shale 1 2 Pierre Shale 1 2 Fox Hills Sandstone 1 4 Fox Hills problem 1 4 BEDROCK TOPOGRAPHY 1 4 Bedrock highs 1 5 Intermediate bedrock surface 1 5 Bedrock valleys 1 5 GLACIATION OF' NORTH DAKOTA — A GENERAL STATEMENT 1 7 PLEISTOCENE SEDIMENTS AND THEIR ASSOCIATED LANDFORMS 1 8 Till 1 8 Landforms associated with till 1 8 Glaciofluvial :materials 22 Ice-contact glaciofluvial sediments 2 2 Landforms associated with ice-contact glaciofluvial sediments 2 2 Proglacial fluvial sediments 2 3 Landforms associated with proglacial fluvial sediments 2 3 Lacustrine sediments 2 3 Landforms associated with lacustrine sediments 2 3 Other postglacial sediments 2 4 ANALYSIS OF THE SURFICIAL TILL IN STUTSMAN COUNTY 2 4 Leaching and caliche 24 Oxidation 2 4 Stone counts 2 5 Lignite within till 2 7 Grain-size analyses of till _ 2 8 Till samples from hummocky stagnation moraine 2 8 Till samples from the Millarton, Eldridge, Buchanan and Grace Cit y moraines and their associated landforms _ . -

Chapter 3, District Resources and Description

CHAPTER 3— District Resources and Description Bridgette Flanders-Wanner / USFWS / Bridgette Flanders-Wanner Grasslands in the Millerdale Waterfowl Production Area. The three wetland management districts manage smaller temporary and seasonal wetlands that draw thousands of noncontiguous tracts of Federal land breeding duck pairs to South Dakota and other parts totaling 1,136,965 acres: 100,094 acres of WPAs and of the Prairie Pothole Region. 1,036,871 acres of conservation easements. This chap ter describes the physical environment and biological CLIMATE CHANGE resources of these district lands, as well as fire and In January 2001, the Department of the Interior is grazing history, cultural resources, visitor services, sued Order 3226, requiring its Federal agencies with socioeconomic environment, and district operations. land management responsibilities to consider potential climate change effects as part of long-range planning endeavors. The U.S. Department of Energy’s report, “Carbon Sequestration Research and Development,” 3.1 Physical Environment concluded that ecosystem protection is important to carbon sequestration and may reduce or prevent loss The districts are located in central and eastern South of carbon currently stored in the terrestrial biosphere. Dakota from west of the Missouri River to the Minnesota The report defines carbon sequestration as “the capture state line, and from the North Dakota border roughly and secure storage of carbon that would otherwise be two-thirds of the way south to the state line of Nebraska. emitted to or remain in the atmosphere.” The increase The prairies of South Dakota have become an eco of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the earth’s atmosphere has logical treasure of biological importance for water been linked to the gradual rise in surface temperature fowl and other migratory birds. -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Huron Wetland Management District Madison Wetland Management District Sand Lake Wetland Management District South Dakota

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Huron Wetland Management District Madison Wetland Management District Sand Lake Wetland Management District South Dakota January 2012 Approved by Stephen D. Guertin, Regional Director Date U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Lakewood, Colorado Prepared by Huron Wetland Management District Room 309 Federal Building 200 Fourth Street SW. Huron, South Dakota 57350 605 / 352 5894 Madison Wetland Management District 23520 SD Highway 19 Madison, South Dakota 57042 605 / 256 2974 Sand Lake Wetland Management District 39650 Sand Lake Drive Columbia, South Dakota 57433 605 / 885 6320 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain–Prairie Region Division of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, Colorado 80228 303 / 236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Comprehensive conservation plan: Huron Wetland Management District, Madison Wetland Management District, and Sand Lake Wetland Management District, South Dakota. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 260 p. Comprehensive Conservation Plan Huron Wetland Management District Madison Wetland Management District Sand Lake Wetland Management District South Dakota Submitted by Concurred with by Clarke Dirks Date Richard A. Coleman, Ph.D. Date Project Leader Assistant Regional Director Huron Wetland Management District U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Huron, South Dakota National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Natoma Buskness Date Paul Cornes Date Project Leader Refuge Supervisor Madison Wetland Management District U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Madison, South Dakota National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Harris Hoistad Date Project Leader Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge Complex Columbia, South Dakota Contents Summary ..................................................................................... -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota December 2012 Approved by Noreen Walsh, Regional Director Date U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Lakewood, Colorado Prepared by Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex 38672 291st Street Lake Andes, South Dakota 57356 605 /487 7603 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain–Prairie Region Division of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, Colorado 80228 303 /236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 218 p. Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota Submitted by Concurred with by Michael J. Bryant Date Bernie Peterson. Date Project Leader Refuge Supervisor, Region 6 Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lake Andes, South Dakota Lakewood, Colorado Matt Hogan Date Assistant Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................... XI Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. XVII CHAPTER 1–Introduction ..................................................................... -

2019 FIRST Harvest Report

SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand Technol.† RM Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank HEFTY H24X8 RRX 2.4 MR 58.2 15.0 1 114.2 492 1 ASGROW AG22X0 § RRX 2.2 R 57.4 14.2 6 112.3 486 2 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC New Richland, MN TITAN PRO 28E8 E3 2.8 R 55.8 14.4 5 112.3 472 3 2019 Soybeans Top 30 Harvest Report HOEGEMEYER 2540 E E3 2.5 R 55.2 14.4 2 113.3 467 4 South Dakota Southeast [SDSE] SALEM, SD REA RX2518 § RRX 2.5 R 54.9 14.5 4 110.4 465 5 Ernie Christensen, McCook County, SD 57048 HOEGEMEYER 2202 NX RRX 2.2 R 54.5 14.3 4 113.3 461 6 All-Season Test 2.1 - 2.8 Day CRM REA RX2639 GC RRX 2.6 R 53.8 14.1 7 114.7 456 7 S2019SDSE04 GENESIS G2140E E3 2.1 R 53.4 14.1 5 112.3 452 8 For Gross Income Top 30 of 54 CREDENZ CZ 2550GTLL LG27 2.5 MR 53.4 14.1 2 110.4 452 9 (Sorted by Yield) Average of (3) Replications LATHAM L 2549R2X RRX 2.5 R 53.1 14.1 2 112.3 450 10 CHAMPION 25X70N RRX 2.5 R 52.9 14.2 2 111.4 448 11 PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Valor, Roundup GENESIS G2181GL LG27 2.2 R 52.6 14.5 1 107.4 445 12 SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non- NK BRAND S20-J5X § RRX 2.0 R 52.4 13.9 14 108.4 444 13 irrigated HEFTY Z2300E E3 2.3 R 52.3 13.8 2 112.3 444 14 SOIL CONDITION: very high P, very high K, 5.9 NK BRAND S21-W8X § RRX 2.1 R 52.2 14.0 5 109.4 442 15 pH, 3.0% OM, 19.3 CEC STINE 25GA62 § LG27 2.5 R 52.0 14.0 2 111.3 441 16 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Conventional W/ Fall Till PIONEER P21A28X § RRX 2.1 R 51.7 14.1 2 105.5 438 17 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup, Select Max HOEGEMEYER 2820 E E3 2.8 R 51.4 15.1 5 112.3 434 18 Applied N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 HEFTY Z2700E E3 2.7 R 51.3 14.7 1 113.3 434 19 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: Jun 12 140.0 /A 30" spacing LATHAM L 2395 LLGT27 LG27 2.3 R 51.2 14.0 5 108.4 434 20 HARVESTED - STAND: Nov 1 111.4 /A DYNA-GRO S24XT08 RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.1 2 113.3 433 22 RENK RS248NX RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.5 2 112.3 432 23 TEST COMMENTS: RENK RS250NX RRX 2.5 R 51.2 14.1 1 112.3 434 21 This was a clean field with a fairly consistent stand of HEFTY H25X0 RRX 2.5 R 50.9 14.3 2 113.3 431 24 soybeans. -

North Dakota State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Peace Garden State

North Dakota State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Peace Garden State North Dakota History The first Europeans in the area arrived the last part of the eighteenth century and were fur traders employed by the Missouri Fur Company. The peopling of the area quickly followed the first exploration with settlements in Selkirk Colony, on the Red and Assiniboine rivers, and the Pembina settlement. Both were established in 1812, but conditions were so difficult that by 1823 Selkirk had become part of the Hudson Bay Company settlement and Pembina had been abandoned. The indigenous tribes of the Dakotas were the Mandans and Arikaras. Eastern tribes that were moved into the area included Hidatsas, Crows, Cheyennes, Creeks, Assiniboines, Yanktonai Dakotas, Teton Dakotas, and Chippewas. The smallpox epidemics in 1782 and 1786 wiped out three-fourths of the Mandans and half of the Hidatsas. The epidemic of 1837, probably introduced by the white fur traders, also had a devastating effect on the native population. Composing the largest settlement at the Red River were the “half-breeds” (called métis) who were the offspring of European fathers (French, Canadian, Scottish, and English) and Native American mothers (Chippewa, Creek, Assiniboine). Many area residents claimed French-Chippewa ancestry. By 1850 more than half of the five to six thousand people living at Fort Garry were métis, with a large percentage being Canadian- born. Settlers began moving into the region in 1849 with the organization of Minnesota Territory and the settlement of Iowa and Minnesota. This immigration brought a number of settlers to southeastern Dakota. Dakota Territory was created by an act of Congress on 2 March 1861 from the area that had previously been Nebraska and Minnesota territories. -

2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results

South Dakota Agricultural agronomy Experiment Station at SDSU SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY® OCTOBER 2020 AGRONOMY, HORTICULTURE, & PLANT SCIENCE DEPARTMENT 2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results Plankinton Jonathan Kleinjan | SDSU Extension Crop Production Associate Kevin Kirby | Agricultural Research Manager Shawn Hawks | Agricultural Research Manager Location: 6 miles north and 4 miles west of Plankinton (57368) in Aurora County, SD (GPS: 43.802972° -98.556917°) Cooperator: Edinger Brothers Soil Type: Houdek-Dudley complex, 0-2% slopes Fertilizer: none Previous crop: corn Tillage: minimum-till Row spacing: 30 inches Seeding Rate: 150,000/acre Herbicide: Pre: 3 oz/acre Fierce (flumioxazin + pyroxasulfone) + 5 oz/acre Metribuzin (metribuzin) + 3.3 pt/acre Prowl H2O (pendimethalin) Post: none Insecticide: none Date seeded: 6/2/2020 Date harvested: 10/16/2020 SDSU Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer in accordance with the nondiscrimination policies of South Dakota State University, the South Dakota Board of Regents and the United States Department of Agriculture. Learn more at extension.sdstate.edu. S-0002-06 2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results Plankinton Table 1. Glyphosate-resistant soybean variety performance results (average of 4 replications - Maturity Group 1 at Plankinton, SD. Variety Information Agronomic Performance Maturity Yield Lodging Score Brand Variety Moisture (%) Rating (bu/ac@13%) (1-5)* LG Seeds C1838RX 1.8 62.8 9.2 1.0 P3 Genetics 2117E 1.7 60.3 9.1 1.0 Peterson Farms Seed 21X16N 1.6 59.8 9.3 1.0 LG Seeds LGS1776RX 1.7 58.4 9.3 1.0 Farmer Check 1 1818R2X 1.8 58.0 9.2 1.0 Farmer Check 2 P19A14X 1.9 57.9 8.8 1.0 Check 14X0 1.4 54.9 9.0 1.0 Trial Average 58.9 9.1 1.0 LSD (0.05)† 3.3 0.4 - C.V.‡ 3.8 3.1 - *Lodging Score (1 = no lodging to 5 = flat on the ground).