Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix L, Bureau of Land Management Worksheets

Palen‐Ford Playa Dunes Description/Location: The proposed Palen‐Ford Playa Dunes NLCS/ ACEC would encompass the entire playa and dune system in the Chuckwalla Valley of eastern Riverside County. The area is bordered on the east by the Palen‐McCoy Wilderness and on the west by Joshua Tree National Park. Included within its boundaries are the existing Desert Lily Preserve ACEC, the Palen Dry Lake ACEC, and the Palen‐Ford Wildlife Habitat Management Area (WHMA). Nationally Significant Values: Ecological Values: The proposed unit would protect one of the major playa/dune systems of the California Desert. The area contains extensive and pristine habitat for the Mojave fringe‐toed lizard, a BLM Sensitive Species and a California State Species of Special Concern. Because the Chuckwalla Valley population occurs at the southern distributional limit for the species, protection of this population is important for the conservation of the species. The proposed unit would protect an entire dune ecosystem for this and other dune‐dwelling species, including essential habitat and ecological processes (i.e., sand source and sand transport systems). The proposed unit would also contribute to the overall linking of five currently isolated Wilderness Areas of northeastern Riverside County (i.e., Palen‐McCoy, Big Maria Mountains, Little Maria Mountains, Riverside Mountains, and Rice Valley) with each other and Joshua Tree National Park, and would protect a large, intact representation of the lower Colorado Desert. Along with the proposed Chuckwalla Chemehuevi Tortoise Linkage NLCS/ ACEC and Upper McCoy NLCS/ ACEC, this unit would provide crucial habitat connectivity for key wildlife species including the federally threatened Agassizi’s desert tortoise and the desert bighorn sheep. -

Orange Sulphur, Colias Eurytheme, on Boneset

Orange Sulphur, Colias eurytheme, on Boneset, Eupatorium perfoliatum, In OMC flitrh Insect Survey of Waukegan Dunes, Summer 2002 Including Butterflies, Dragonflies & Beetles Prepared for the Waukegan Harbor Citizens' Advisory Group Jean B . Schreiber (Susie), Chair Principal Investigator : John A. Wagner, Ph . D . Associate, Department of Zoology - Insects Field Museum of Natural History 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605 Telephone (708) 485 7358 home (312) 665 7016 museum Email jwdw440(q-), m indsprinq .co m > home wagner@,fmnh .orq> museum Abstract: From May 10, 2002 through September 13, 2002, eight field trips were made to the Harbor at Waukegan, Illinois to survey the beach - dunes and swales for Odonata [dragonfly], Lepidoptera [butterfly] and Coleoptera [beetles] faunas between Midwest Generation Plant on the North and the Outboard Marine Corporation ditch at the South . Eight species of Dragonflies, fourteen species of Butterflies, and eighteen species of beetles are identified . No threatened or endangered species were found in this survey during twenty-four hours of field observations . The area is undoubtedly home to many more species than those listed in this report. Of note, the endangered Karner Blue butterfly, Lycaeides melissa samuelis Nabakov was not seen even though it has been reported from Illinois Beach State Park, Lake County . The larval food plant, Lupinus perennis, for the blue was not observed at Waukegan. The limestone seeps habitat of the endangered Hines Emerald dragonfly, Somatochlora hineana, is not part of the ecology here . One surprise is the. breeding population of Buckeye butterflies, Junonia coenid (Hubner) which may be feeding on Purple Loosestrife . The specimens collected in this study are deposited in the insect collection at the Field Museum . -

Arid and Semi-Arid Lakes

WETLAND MANAGEMENT PROFILE ARID AND SEMI-ARID LAKES Arid and semi-arid lakes are key inland This profi le covers the habitat types of ecosystems, forming part of an important wetlands termed arid and semi-arid network of feeding and breeding habitats for fl oodplain lakes, arid and semi-arid non- migratory and non-migratory waterbirds. The fl oodplain lakes, arid and semi-arid lakes support a range of other species, some permanent lakes, and arid and semi-arid of which are specifi cally adapted to survive in saline lakes. variable fresh to saline water regimes and This typology, developed by the Queensland through times when the lakes dry out. Arid Wetlands Program, also forms the basis for a set and semi-arid lakes typically have highly of conceptual models that are linked to variable annual surface water infl ows and vary dynamic wetlands mapping, both of which can in size, depth, salinity and turbidity as they be accessed through the WetlandInfo website cycle through periods of wet and dry. The <www.derm/qld.gov.au/wetlandinfo>. main management issues affecting arid and semi-arid lakes are: water regulation or Description extraction affecting local and/or regional This wetland management profi le focuses on the arid hydrology, grazing pressure from domestic and semi-arid zone lakes found within Queensland’s and feral animals, weeds and tourism impacts. inland-draining catchments in the Channel Country, Desert Uplands, Einasleigh Uplands and Mulga Lands bioregions. There are two broad types of river catchments in Australia: exhoreic, where most rainwater eventually drains to the sea; and endorheic, with internal drainage, where surface run-off never reaches the sea but replenishes inland wetland systems. -

Ultrasociality: When Institutions Make a Difference

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304625948 Ultrasociality: When institutions make a difference Article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences · June 2016 DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X15001089 CITATIONS READS 0 5 3 authors, including: Petr Houdek Julie Novakova Vysoká škola ekonomická v Praze Charles University in Prague 11 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS 6 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Petr Houdek Retrieved on: 20 September 2016 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2016), Page 1 of 60 doi:10.1017/S0140525X1500059X, e92 The economic origins of ultrasociality John Gowdy Department of Economics and Department of Science and Technology Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 12180 [email protected] http://www.economics.rpi.edu/pl/people/john-gowdy Lisi Krall Department of Economics, State University of New York (SUNY) at Cortland, Cortland, NY 13045 [email protected] Abstract: Ultrasociality refers to the social organization of a few species, including humans and some social insects, having a complex division of labor, city-states, and an almost exclusive dependence on agriculture for subsistence. We argue that the driving forces in the evolution of these ultrasocial societies were economic. With the agricultural transition, species could directly produce their own food and this was such a competitive advantage that those species now dominate the planet. Once underway, this transition was propelled by the selection of within-species groups that could best capture the advantages of (1) actively managing the inputs to food production, (2) a more complex division of labor, and (3) increasing returns to larger scale and larger group size. -

Origins of Six Species of Butterflies Migrating Through Northeastern

diversity Article Origins of Six Species of Butterflies Migrating through Northeastern Mexico: New Insights from Stable Isotope (δ2H) Analyses and a Call for Documenting Butterfly Migrations Keith A. Hobson 1,2,*, Jackson W. Kusack 2 and Blanca X. Mora-Alvarez 2 1 Environment and Climate Change Canada, 11 Innovation Blvd., Saskatoon, SK S7N 0H3, Canada 2 Department of Biology, University of Western Ontario, Ontario, ON N6A 5B7, Canada; [email protected] (J.W.K.); [email protected] (B.X.M.-A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Determining migratory connectivity within and among diverse taxa is crucial to their conservation. Insect migrations involve millions of individuals and are often spectacular. However, in general, virtually nothing is known about their structure. With anthropogenically induced global change, we risk losing most of these migrations before they are even described. We used stable hydrogen isotope (δ2H) measurements of wings of seven species of butterflies (Libytheana carinenta, Danaus gilippus, Phoebis sennae, Asterocampa leilia, Euptoieta claudia, Euptoieta hegesia, and Zerene cesonia) salvaged as roadkill when migrating in fall through a narrow bottleneck in northeast Mexico. These data were used to depict the probabilistic origins in North America of six species, excluding the largely local E. hegesia. We determined evidence for long-distance migration in four species (L. carinenta, E. claudia, D. glippus, Z. cesonia) and present evidence for panmixia (Z. cesonia), chain (Libytheana Citation: Hobson, K.A.; Kusack, J.W.; Mora-Alvarez, B.X. Origins of Six carinenta), and leapfrog (Danaus gilippus) migrations in three species. Our investigation underlines Species of Butterflies Migrating the utility of the stable isotope approach to quickly establish migratory origins and connectivity in through Northeastern Mexico: New butterflies and other insect taxa, especially if they can be sampled at migratory bottlenecks. -

A Great Basin-Wide Dry Episode During the First Half of the Mystery

Quaternary Science Reviews 28 (2009) 2557–2563 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quascirev A Great Basin-wide dry episode during the first half of the Mystery Interval? Wallace S. Broecker a,*, David McGee a, Kenneth D. Adams b, Hai Cheng c, R. Lawrence Edwards c, Charles G. Oviatt d, Jay Quade e a Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, 61 Route 9W, Palisades, NY 10964-8000, USA b Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV 89512, USA c Department of Geology & Geophysics, University of Minnesota, 310 Pillsbury Drive SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA d Department of Geology, Kansas State University, Thompson Hall, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA e Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, 1040 E. 4th Street, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA article info abstract Article history: The existence of the Big Dry event from 14.9 to 13.8 14C kyrs in the Lake Estancia New Mexico record Received 25 February 2009 suggests that the deglacial Mystery Interval (14.5–12.4 14C kyrs) has two distinct hydrologic parts in the Received in revised form western USA. During the first, Great Basin Lake Estancia shrank in size and during the second, Great Basin 15 July 2009 Lake Lahontan reached its largest size. It is tempting to postulate that the transition between these two Accepted 16 July 2009 parts of the Mystery Interval were triggered by the IRD event recorded off Portugal at about 13.8 14C kyrs which post dates Heinrich event #1 by about 1.5 kyrs. This twofold division is consistent with the record from Hulu Cave, China, in which the initiation of the weak monsoon event occurs in the middle of the Mystery Interval at 16.1 kyrs (i.e., about 13.8 14C kyrs). -

Ground-Water Resources-Reconnaissance Series Report 20

- STATE OF NEVADA ~~~..._.....,.,.~.:RVA=rl~ AND NA.I...U~ a:~~::~...... _ __,_ Carson City_ GROUND-WATER RESOURCES-RECONNAISSANCE SERIES REPORT 20 GROUND- WATER APPRAISAL OF THE BLACK ROCK DESERT AREA NORTHWESTERN NEVADA By WILLIAM C. SINCLAIR Geologist Price $1.00 PLEASE DO NOT REMO V~ f ROM T. ':'I S OFFICE ;:: '· '. ~- GROUND-WATER RESOURCES--RECONNAISSANCE SERIES .... Report 20 =· ... GROUND-WATER APPRAISAL OF THE BLACK ROCK OESER T AREA NORTHWESTERN NEVADA by William C. Sinclair Geologist ~··· ··. Prepared cooperatively by the Geological SUrvey, U. S. Department of Interior October, 1963 FOREWORD This reconnaissance apprais;;l of the ground~water resources of the Black Rock Desert area in northwestern Nevada is the ZOth in this series of reports. Under this program, which was initiated following legislative action • in 1960, reports on the ground-water resources of some 23 Nevada valleys have been made. The present report, entitled, "Ground-Water Appraisal of the Black Rock Desert Area, Northwe$tern Nevada", was prepared by William C. Sinclair, Geologist, U. s. Geological Survey. The Black Rock Desert area, as defined in this report, differs some~ what from the valleys discussed in previous reports. The area is very large with some 9 tributary basins adjoining the extensive playa of Black Rock Desert. The estimated combined annual recharge of all the tributary basins amounts to nearly 44,000 acre-feet, but recovery of much of this total may be difficult. Water which enters into the ground water under the central playa probably will be of poor quality for irrigation. The development of good produci1>g wells in the old lake sediments underlying the central playa appears doubtful. -

Quantitative Appraisal of Non-Irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program 10-22-2018 Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Agribusiness Commons, Agricultural Economics Commons, Agricultural Science Commons, Applied Mathematics Commons, Applied Statistics Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Riggs, Shelby, "Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 117. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/117 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Ag Land in South Dakota An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska – Lincoln By Shelby Riggs, BS Agricultural Economics College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources October 22nd, 2018 Faculty Mentor: Jeffrey Stokes, PhD, Agricultural Economics Abstract This appraisal attempts to remove subjectivity from the appraisal process and replace it with quantitative analysis of known data to generate fair market value the subject property. Two methods of appraisal will be used, the income approach and the sales comparison approach. For the income approach, I use the average cash rent for the region, the current property taxes for the subject property, and a capitalization rate based on Stokes’ (2018) capitalization rate formula to arrive at my income-based valuation. -

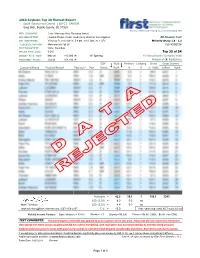

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report Top 30 of 54

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report South Dakota East Central [ SDEC ] CAVOUR Greg Bich, Beadle County, SD 57324 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC, New Richland, MN PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Harness Xtra, Roundup (twice) SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non-irrigated All-Season Test SOIL CONDITIONS: Very low P, very high K, 5.9 pH, 3.0% OM, 20.1 CEC Maturity Group 1.6 - 2.3 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Minimum w/o fall till S2018SDEC06 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup APPLIED N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 Top 30 of 54 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: May 26 140,000 /A 30" Spacing For Gross Income (Sorted by Yield) HARVESTED - STAND: Oct 23 108,100 /A Average of (2) Replications SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand†Technol.† Mat. Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank Averages = 42.8 10.1 1 108.1 $343 LSD (0.10) = 8.3 0.5 ns Mark Tollefson LSD (0.25) = 4.4 0.3 ns [email protected], (507) 456-2357 C.V. = 15.0 Prev. years avg. yield, 45.7 bu/a, 10 yrs Yield & Income Factors: Base Moisture = 13.0% Shrink = 1.3 Drying = $0.020 Prices = $8.00 GMO; $8.00 non-GMO TEST COMMENTS: The preemergence herbicide was applied to only a portion of the test area. Areas that did not receive this treatment were weedy the entire season as glphosate did not control everything. One replication was not harvested due to extreme weed pressure. Soybean yield was great in areas with good weed control (1 replication) but dropped considerably elsewhere. -

Butterflies of Citrus County and Host Plants

Butterflies of Citrus County ~---4- --•;... ____ - Family I Species Host plant Hesperiidae SkipQers Phocides Qigmalion Mangrove Skipper ~mangrove herbs, vines, shrubs, and trees in the pea family (Fabaceae) including false indigobush (Amorpha fruticosa L.), American hogpeanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata [L.) Fernald), Atlantic pidgeonwings or butterfly pea (Clitoria mariana L.), groundnut (Apios ~vreus clarus Silver-spotted Skip~ americana Medik.), American wisteria (Wisteria frutescens [L.) Poir.) and the introduced Dixie ticktrefoil (Desmodium tortuosum [Sw.] DC.), kudzu (Pueraria montana [Lour.] Merr.), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), Chinese wisteria (Wisteria sinensis [Sims) DC.) and a variety of other legumes Urbanus prqJg_µs Long-t~.Ued SkiQpec vine legumes including various beans (Phaseolus), hog peanuts (Amphicarpa bracteata), beggar's ticks (Desmodium), blue peas (Clitoria), and wisteria (Wisteria) Various legumes inclu ding wild and cu ltivated beans (Phaseolus), begga r's ticks Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail (Desmodium), and bl ue peas (Clit oria ) -· Beggar\'s ticks (Desmodium); occasionally false indigo (Baptisia) and bush clover Achalarus ly-ciades Hoar.y_r;_ggg {Lespedeza); all in the pea family {Fabaceae) - pea family (Fabaceae) including beggar's ticks (Desmodium), bush clover (Lespedeza), Thor'lbes P'llades Northern Cloud'lwing clover (Trifolium), lotus (Hosackia), and others. -----· Thory-bes bathy-llus Southern Cloudywing Potato bean, Apios americana. Ozark milkvetch, Astragalus distortus var. engelmanni ~ ---- Lespedezas (Lespedeza spp .) are reported as well as Florida Hoarypea (Tephrosia l ibQr:_y_bes confusis Confused Cloudy-wing florid a) . -· -- -------- Staphy:lus hayhurst_ii Ha yh u r?J?-5.IAJ.\QQ Wi ri_g Lambsquart ers {Che nopodium) in the goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae ), and occasiona lly chaff flower (Alternanthera) in the pigweed family (Amaranthaceae). -

User Notes: Las Cruces, New Mexico, National Wetlands Inventory

USER NOTES : LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO, NATIONAL WETLANDS INVENTORY MAP Map Preparation The wetland classifications that appear on the Las Cruces NWI Base Map are in accordance with Cowardin et al .(1977) . The delineations were produced through stereoscope interpretation of 1 :110,000-scale color infrared aerial photographs taken in February, 1971, and 1 :80,000-scale bladk-and-white-aerial photographs taken in March, 1977 . The delineations were enlarged using a zoom transferscope to overlays of 1 :24,000-scale and 1 :62,500-scale . These overlays were then transferred to 1 :100,000-scale to produce the Base Map . Aerial photographs were unavailable for the western portion of the Las Cruces area 1 :62,500-scale map, the western and southern portion of the Afton area 1 :62,500-scale map, and the eastern portions of the White Sands NW, Davies Tank, Newman NW, and Newman SW area 1 :24,000-scale maps . These areas are therefore without wetland designations on the Las Cruces NWI Base Map . Extensive field checks of the delineated wetlands of the Las Cruces NWI Base Map were conducted in June, 1981 to determine the accuracy of the aerial photointerpretation and to provide qualifying descriptions of mapped wetland designations . The user of the map is cautioned that, due to the limitation of mapping primarily through aerial photointerpretation, a small percentage of wetlands may have gone unidentified . Changes in the landscape could have occurred since the time of photography, therefore some discrepancies between the map and current field conditions may exist . Any discrepancies that are encountered in the use of this map should be brought to the attention of Warren Hagenbuck, Regional Wetlands Coordinator, U . -

Selected Qualitative Parameters Above-Ground Phytomass of the Lenor-First Slovak Cultivar of Festulolium A

Acta fytotechn zootechn, 22, 2019(1): 13–16 http://www.acta.fapz.uniag.sk Original Paper Selected qualitative parameters above-ground phytomass of the Lenor-first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A. et Gr. Peter Hric*, Ľuboš Vozár, Peter Kovár Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic Article Details: Received: 2018-10-04 | Accepted: 2018-11-06 | Available online: 2019-01-31 https://doi.org/10.15414/afz.2019.22.01.13-16 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License The aim of this experiment was to compare selected qualitative parameters in above-ground phytomass of the first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A et. Gr. cv. Lenor in comparison to earlier registered cultivars Felina and Hykor. The pot experiment was conducted at the Demonstrating and Research base of the Department of Grassland Ecosystems and Forage Crops, Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra (Slovak Republic) with controlled moisture conditions (shelter) in 2017. Content of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, crude fibre and water soluble carbohydrates were determined from dry above-ground phytomass of grasses. The significantly highest (P <0.05) nitrogen content in average of cuts was in above-ground phytomass of Felina (30.3 g kg-1) compared to Hykor (25.4 g kg-1) and new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (25.0 g kg-1). The lowest phosphorus content was found out in hybrid Lenor (3.4 g kg-1). In average of three cuts, the lowest concentration of potassium was in new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (5.8 g kg-1). The lowest content of calcium was found out in hybrid Lenor (7.0 g kg-1).