Ultrasociality: When Institutions Make a Difference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantitative Appraisal of Non-Irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program 10-22-2018 Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Agribusiness Commons, Agricultural Economics Commons, Agricultural Science Commons, Applied Mathematics Commons, Applied Statistics Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Riggs, Shelby, "Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 117. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/117 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Ag Land in South Dakota An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska – Lincoln By Shelby Riggs, BS Agricultural Economics College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources October 22nd, 2018 Faculty Mentor: Jeffrey Stokes, PhD, Agricultural Economics Abstract This appraisal attempts to remove subjectivity from the appraisal process and replace it with quantitative analysis of known data to generate fair market value the subject property. Two methods of appraisal will be used, the income approach and the sales comparison approach. For the income approach, I use the average cash rent for the region, the current property taxes for the subject property, and a capitalization rate based on Stokes’ (2018) capitalization rate formula to arrive at my income-based valuation. -

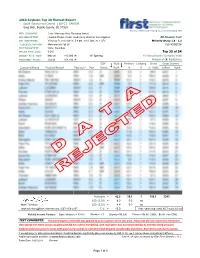

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report Top 30 of 54

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report South Dakota East Central [ SDEC ] CAVOUR Greg Bich, Beadle County, SD 57324 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC, New Richland, MN PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Harness Xtra, Roundup (twice) SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non-irrigated All-Season Test SOIL CONDITIONS: Very low P, very high K, 5.9 pH, 3.0% OM, 20.1 CEC Maturity Group 1.6 - 2.3 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Minimum w/o fall till S2018SDEC06 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup APPLIED N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 Top 30 of 54 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: May 26 140,000 /A 30" Spacing For Gross Income (Sorted by Yield) HARVESTED - STAND: Oct 23 108,100 /A Average of (2) Replications SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand†Technol.† Mat. Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank Averages = 42.8 10.1 1 108.1 $343 LSD (0.10) = 8.3 0.5 ns Mark Tollefson LSD (0.25) = 4.4 0.3 ns [email protected], (507) 456-2357 C.V. = 15.0 Prev. years avg. yield, 45.7 bu/a, 10 yrs Yield & Income Factors: Base Moisture = 13.0% Shrink = 1.3 Drying = $0.020 Prices = $8.00 GMO; $8.00 non-GMO TEST COMMENTS: The preemergence herbicide was applied to only a portion of the test area. Areas that did not receive this treatment were weedy the entire season as glphosate did not control everything. One replication was not harvested due to extreme weed pressure. Soybean yield was great in areas with good weed control (1 replication) but dropped considerably elsewhere. -

Selected Qualitative Parameters Above-Ground Phytomass of the Lenor-First Slovak Cultivar of Festulolium A

Acta fytotechn zootechn, 22, 2019(1): 13–16 http://www.acta.fapz.uniag.sk Original Paper Selected qualitative parameters above-ground phytomass of the Lenor-first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A. et Gr. Peter Hric*, Ľuboš Vozár, Peter Kovár Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic Article Details: Received: 2018-10-04 | Accepted: 2018-11-06 | Available online: 2019-01-31 https://doi.org/10.15414/afz.2019.22.01.13-16 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License The aim of this experiment was to compare selected qualitative parameters in above-ground phytomass of the first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A et. Gr. cv. Lenor in comparison to earlier registered cultivars Felina and Hykor. The pot experiment was conducted at the Demonstrating and Research base of the Department of Grassland Ecosystems and Forage Crops, Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra (Slovak Republic) with controlled moisture conditions (shelter) in 2017. Content of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, crude fibre and water soluble carbohydrates were determined from dry above-ground phytomass of grasses. The significantly highest (P <0.05) nitrogen content in average of cuts was in above-ground phytomass of Felina (30.3 g kg-1) compared to Hykor (25.4 g kg-1) and new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (25.0 g kg-1). The lowest phosphorus content was found out in hybrid Lenor (3.4 g kg-1). In average of three cuts, the lowest concentration of potassium was in new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (5.8 g kg-1). The lowest content of calcium was found out in hybrid Lenor (7.0 g kg-1). -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota December 2012 Approved by Noreen Walsh, Regional Director Date U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Lakewood, Colorado Prepared by Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex 38672 291st Street Lake Andes, South Dakota 57356 605 /487 7603 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain–Prairie Region Division of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, Colorado 80228 303 /236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 218 p. Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota Submitted by Concurred with by Michael J. Bryant Date Bernie Peterson. Date Project Leader Refuge Supervisor, Region 6 Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lake Andes, South Dakota Lakewood, Colorado Matt Hogan Date Assistant Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................... XI Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. XVII CHAPTER 1–Introduction ..................................................................... -

2019 FIRST Harvest Report

SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand Technol.† RM Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank HEFTY H24X8 RRX 2.4 MR 58.2 15.0 1 114.2 492 1 ASGROW AG22X0 § RRX 2.2 R 57.4 14.2 6 112.3 486 2 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC New Richland, MN TITAN PRO 28E8 E3 2.8 R 55.8 14.4 5 112.3 472 3 2019 Soybeans Top 30 Harvest Report HOEGEMEYER 2540 E E3 2.5 R 55.2 14.4 2 113.3 467 4 South Dakota Southeast [SDSE] SALEM, SD REA RX2518 § RRX 2.5 R 54.9 14.5 4 110.4 465 5 Ernie Christensen, McCook County, SD 57048 HOEGEMEYER 2202 NX RRX 2.2 R 54.5 14.3 4 113.3 461 6 All-Season Test 2.1 - 2.8 Day CRM REA RX2639 GC RRX 2.6 R 53.8 14.1 7 114.7 456 7 S2019SDSE04 GENESIS G2140E E3 2.1 R 53.4 14.1 5 112.3 452 8 For Gross Income Top 30 of 54 CREDENZ CZ 2550GTLL LG27 2.5 MR 53.4 14.1 2 110.4 452 9 (Sorted by Yield) Average of (3) Replications LATHAM L 2549R2X RRX 2.5 R 53.1 14.1 2 112.3 450 10 CHAMPION 25X70N RRX 2.5 R 52.9 14.2 2 111.4 448 11 PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Valor, Roundup GENESIS G2181GL LG27 2.2 R 52.6 14.5 1 107.4 445 12 SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non- NK BRAND S20-J5X § RRX 2.0 R 52.4 13.9 14 108.4 444 13 irrigated HEFTY Z2300E E3 2.3 R 52.3 13.8 2 112.3 444 14 SOIL CONDITION: very high P, very high K, 5.9 NK BRAND S21-W8X § RRX 2.1 R 52.2 14.0 5 109.4 442 15 pH, 3.0% OM, 19.3 CEC STINE 25GA62 § LG27 2.5 R 52.0 14.0 2 111.3 441 16 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Conventional W/ Fall Till PIONEER P21A28X § RRX 2.1 R 51.7 14.1 2 105.5 438 17 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup, Select Max HOEGEMEYER 2820 E E3 2.8 R 51.4 15.1 5 112.3 434 18 Applied N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 HEFTY Z2700E E3 2.7 R 51.3 14.7 1 113.3 434 19 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: Jun 12 140.0 /A 30" spacing LATHAM L 2395 LLGT27 LG27 2.3 R 51.2 14.0 5 108.4 434 20 HARVESTED - STAND: Nov 1 111.4 /A DYNA-GRO S24XT08 RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.1 2 113.3 433 22 RENK RS248NX RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.5 2 112.3 432 23 TEST COMMENTS: RENK RS250NX RRX 2.5 R 51.2 14.1 1 112.3 434 21 This was a clean field with a fairly consistent stand of HEFTY H25X0 RRX 2.5 R 50.9 14.3 2 113.3 431 24 soybeans. -

2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results

South Dakota Agricultural agronomy Experiment Station at SDSU SOUTH DAKOTA STATE UNIVERSITY® OCTOBER 2020 AGRONOMY, HORTICULTURE, & PLANT SCIENCE DEPARTMENT 2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results Plankinton Jonathan Kleinjan | SDSU Extension Crop Production Associate Kevin Kirby | Agricultural Research Manager Shawn Hawks | Agricultural Research Manager Location: 6 miles north and 4 miles west of Plankinton (57368) in Aurora County, SD (GPS: 43.802972° -98.556917°) Cooperator: Edinger Brothers Soil Type: Houdek-Dudley complex, 0-2% slopes Fertilizer: none Previous crop: corn Tillage: minimum-till Row spacing: 30 inches Seeding Rate: 150,000/acre Herbicide: Pre: 3 oz/acre Fierce (flumioxazin + pyroxasulfone) + 5 oz/acre Metribuzin (metribuzin) + 3.3 pt/acre Prowl H2O (pendimethalin) Post: none Insecticide: none Date seeded: 6/2/2020 Date harvested: 10/16/2020 SDSU Extension is an equal opportunity provider and employer in accordance with the nondiscrimination policies of South Dakota State University, the South Dakota Board of Regents and the United States Department of Agriculture. Learn more at extension.sdstate.edu. S-0002-06 2020 South Dakota Soybean Variety Trial Results Plankinton Table 1. Glyphosate-resistant soybean variety performance results (average of 4 replications - Maturity Group 1 at Plankinton, SD. Variety Information Agronomic Performance Maturity Yield Lodging Score Brand Variety Moisture (%) Rating (bu/ac@13%) (1-5)* LG Seeds C1838RX 1.8 62.8 9.2 1.0 P3 Genetics 2117E 1.7 60.3 9.1 1.0 Peterson Farms Seed 21X16N 1.6 59.8 9.3 1.0 LG Seeds LGS1776RX 1.7 58.4 9.3 1.0 Farmer Check 1 1818R2X 1.8 58.0 9.2 1.0 Farmer Check 2 P19A14X 1.9 57.9 8.8 1.0 Check 14X0 1.4 54.9 9.0 1.0 Trial Average 58.9 9.1 1.0 LSD (0.05)† 3.3 0.4 - C.V.‡ 3.8 3.1 - *Lodging Score (1 = no lodging to 5 = flat on the ground). -

Biomass Yield from Planted Mixtures and Monocultures of Native Prairie

Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 186 (2014) 148–159 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agee Biomass yield from planted mixtures and monocultures of native prairie vegetation across a heterogeneous farm landscape a,∗ a b b b Cody J. Zilverberg , W. Carter Johnson , Vance Owens , Arvid Boe , Tom Schumacher , b c d a e Kurt Reitsma , Chang Oh Hong , Craig Novotny , Malia Volke , Brett Werner a Natural Resource Management, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD 57007, United States b Plant Science, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD 57007, United States c Department of Life Science and Environmental Biochemistry, Pusan National University, Miryang 627-706, South Korea d EcoSun Prairie Farms, Brookings, SD 57007, United States e Program in Environmental Studies, Centre College, Danville, KY 40422, United States a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Farms in the glaciated tallgrass prairie region of North America are topographically heterogeneous with Received 27 August 2013 wide-ranging soil quality. This environmental heterogeneity may affect choice and placement of species Received in revised form planted for biomass production. We designed replicated experiments and monitored farm-scale produc- 27 December 2013 tion to evaluate the effects of landscape position, vegetation type, and year on yields of monocultures Accepted 23 January 2014 and mixtures. Research was conducted on a 262-ha South Dakota working farm where cropland had been replanted with a variety of native grassland types having biofuel feedstock potential. Vegetation Keywords: type (diverse mixture or switchgrass [Panicum virgatum L.] monoculture) and year interacted to influence Switchgrass Biofuel yield in replicated experiments (p < 0.10). -

Soil Productivity Ratings and Estimated Yields for Moody County, South Dakota D

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Technical Bulletins SDSU Agricultural Experiment Station 2011 Soil Productivity Ratings and Estimated Yields for Moody County, South Dakota D. D. Malo Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_tb Recommended Citation Malo, D. D., "Soil Productivity Ratings and Estimated Yields for Moody County, South Dakota" (2011). Technical Bulletins. Paper 11. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_tb/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SDSU Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TB101 Campbell Marshall Corson McPherson Harding Brown Perkins Roberts Walworth Edmunds Day Grant Dewey Potter Faulk Codington Spink Butte Clark Ziebach Deuel Sully Hamlin Meade Hyde Hand Hughes Beadle Brookings Stanley Kingsbury Lawrence Haakon Buffalo Jerauld Miner Moody Pennington Sanborn Lake Jones Lyman Hanson Custer Jackson Brule Aurora Minnehaha Davison McCook Mellette Douglas Shannon Tripp Hutchinson Turner Fall River Charles Lincoln Bennett Todd Gregory Mix Bon Yankton Homme Clay nion U Soil Productivity Ratings and Estimated Yields for Moody County, South Dakota South Dakota State University Agricultural Experiment Station CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . 1 DATA . 2 METHODS . 2 YIELD and SOIL PRODUCTIVITY RATING RESULTS . 2 SUMMARY . 5 LITERATURE CITED . 6 TABLE 1 (Moody County, South Dakota, Yield Information and Soil Productivity Ratings) . 8 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN TABLE 1 . -

(Phaseolus Vulgaris) Grown in Elevated CO2 on Apatite Dissolution Brian Matthew Orm Ra University of Maine, [email protected]

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-13-2017 Influence of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Grown in Elevated CO2 on Apatite Dissolution Brian Matthew orM ra University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Biogeochemistry Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Recommended Citation Morra, Brian Matthew, "Influence of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Grown in Elevated CO2 on Apatite Dissolution" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2642. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2642 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. INFLUENCE OF COMMON BEAN (PHASEOLUS VULGARIS) GROWN IN ELEVATED CO2 ON APATITE DISSOLUTION By By Brian Morra B.S. University of Idaho, 2012 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Earth and Climate Sciences) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2017 Advisory Committee: Amanda Olsen, Associate Professor, Earth and Climate Sciences, Adviser Aria Amirbahman, Professor, Civil and Environmental Engineering Stephanie Burnett, Associate Professor, School of Food and Agriculture INFLUENCE OF COMMON BEAN (PHASEOLUS VULGARIS) GROWN IN ELEVATED CO2 ON APATITE DISSOLUTION By Brian Matthew Morra Thesis Advisor: Dr. Amanda Olsen An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Earth and Climate Sciences) May 2017 Elevated concentrations of atmospheric CO2 brought about by human activity creates changes in plant morphology, growth rate and exudate production. -

Prairiewinds Sd1, Inc. Application to the South

PRAIRIEWINDS SD1, INC. APPLICATION TO THE SOUTH DAKOTA PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION FOR A FACILITY PERMIT PRAIRIEWINDS SD1 WIND ENERGY FACILITY AND ASSOCIATED COLLECTION SUBSTATION AND ELECTRIC INTERCONNECTION SYSTEM DECEMBER 2009 Prepared for: PrairieWinds SD1, Inc. Prepared by: 2026 Samco Road, Ste. 101 Rapid City, South Dakota 57702 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... 1 2.0 FACILITY PERMIT APPLICATION ................................................................................... 2 3.0 COMPLETENESS CHECKLIST........................................................................................ 5 4.0 NAMES OF PARTICIPANTS (ARSD 20:10:22:06) ........................................................ 20 5.0 NAME OF OWNER AND MANAGER (ARSD 20:10:22:07) ........................................... 20 6.0 PURPOSE OF, AND DEMAND FOR, THE WIND ENERGY FACILITY AND TRANSMISSION FACILITY (ARSD 20:10:22:08, 20:10:22:10)................................................ 20 6.1 WIND RESOURCE AREAS ........................................................................................ 21 6.2 RENEWABLE POWER DEMAND............................................................................... 22 6.3 TRANSMISSION FACILITY DEMAND........................................................................ 23 7.0 ESTIMATED COST OF THE WIND ENERGY FACILITY AND TRANSMISSION FACILITY (ARSD 20:10:22:09)................................................................................................. -

Forage Conservation

14th International Symposium FORAGE CONSERVATION Brno, Czech Republic, March 17-19, 2010 Conference Proceedings NutriVet Ltd., Poho řelice, CZ University of Veterinary and Pharmaceutical Sciences Brno, CZ Mendel University in Brno, CZ Animal Production Research Centre Nitra, SK Institute of Animal Science Prague, Uh řin ěves, CZ 14 th INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM FORAGE CONSERVATION 17 - 19 th MARCH, 2010 Brno, Czech Republic 2010 Organizing committee: Ing. Václav JAMBOR, CSc. Prof. Dipl. Ing. Ladislav ZEMAN, Csc. Prof. Doc. MVDr. Ing. Petr DOLEŽAL, CSc. Prof. Ing. František HRAB Ě, CSc. Doc.Ing. Ji ří SKLÁDANKA, PhD. Ing. Lubica RAJ ČAKOVÁ, Ph.D. Ing. Mária CHRENKOVÁ, Ph.D. Ing. Milan GALLO, Ph.D. Ing. Radko LOU ČKA, CSc. Doc. MVDr. Josef ILLEK, DrSc. Further copies available from: NutriVet Ltd. Víde ňská 1023 691 23 Poho řelice Czech Republic E-mail: [email protected] Tel./fax.: +420-519-424247, mobil: + 420-606-764260 ISBN 978-80-7375-386-3 © Mendel University Brno, 2010 Published for the 14 th International Symposium of Forage Conservation, 17-19 th March, 2010 Brno by MU Brno (Mendel University Brno, CZ) Editors: V. Jambor, S. Jamborová, B. Vosynková, P. Procházka, D. Vosynková, D. Kumprechtová, General Sponzors WWW.LIMAGRAINCENTRALEEUROPE.COM WWW.BIOFERM.COM Sponzors Section 1: Forage production - yield, quality, fertilization WWW.PIONEER.COM Section 2: Fermentation process of forage - harvest, preservation and storage WWW.ADDCON.DE Section 3: Utilization, nutritive value and hygienic aspects of pereserved forages on production health of animals WWW.ALLTECH.COM Section 4: Production of biogass by conserved forages, greenhouse gases and animal agriculture, ecology WWW.SCHAUMANN.CZ WWW.CHR-HANSEN.COM WWW.MIKROP.CZ WWW.BIOMIN.NET WWW.OSEVABZENEC.CZ TABLE OF CONTENTS PRODUCTION AND FINALIZATION OF THE MILK IN THE EU KUČERA J. -

POSTER SESSION 4Th Annual Meeting July 16, 2019 Hyatt Regency • Sacramento, California USA POSTER SESSION 4:00 P.M

POSTER SESSION 4th Annual Meeting July 16, 2019 Hyatt Regency • Sacramento, California USA POSTER SESSION 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m., Tuesday, July 16 PRESENTER: Guihua Chen describe, and illustrate by a limited example, the concepts and assessment of soil’s capacity POSTER 1 measured through its capability, and condition as contributors to an overall soil security framework. The links to other notions such as threats to soil and soil functions are made. California Healthy Soils Program: Promoting Adoption 1 1 2 of Conservation Agricultural Management Practices on Authors: Alex McBratney , Damien Field , Cristine Morgan California Agricultural Lands Affiliations: 1) The University of Sydney, School of Life and Environmental Sciences & Sydney Research Description: Institute of Agriculture, NSW, Australia; 2) Soil Health Institute California is the national leader in agricultural production and exports. Among 100 million acres of California land, about 40% is used for agriculture. Conventional management practices PRESENTER: Alex McBratney and intensive production systems may result in soil degradation such as loss of soil organic POSTER 4 matter and biodiversity, nutrient depletion, and salinity. Healthy soils are crucial to support agricultural production, increase resilience to natural disasters such as drought and pests, Tea-Bag Index: A Method for Promoting Soil Health and and maintain sustainability in the long term. Healthy soils also play a key role in mitigating Security in Schools greenhouse gas (GHGs) emissions through carbon sequestration. Research Description: California Department of Food and Agriculture leads the Healthy Soils Program (HSP) that Soil organic matter (SOM) is critical for soil health. However, the SOM quality is variable stems from California Healthy Soils Initiative (HSI), a collaboration of state agencies and and indicates its potential for long-term storage.