Biomass Yield from Planted Mixtures and Monocultures of Native Prairie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultrasociality: When Institutions Make a Difference

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304625948 Ultrasociality: When institutions make a difference Article in Behavioral and Brain Sciences · June 2016 DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X15001089 CITATIONS READS 0 5 3 authors, including: Petr Houdek Julie Novakova Vysoká škola ekonomická v Praze Charles University in Prague 11 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS 6 PUBLICATIONS 9 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Petr Houdek Retrieved on: 20 September 2016 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2016), Page 1 of 60 doi:10.1017/S0140525X1500059X, e92 The economic origins of ultrasociality John Gowdy Department of Economics and Department of Science and Technology Studies, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY 12180 [email protected] http://www.economics.rpi.edu/pl/people/john-gowdy Lisi Krall Department of Economics, State University of New York (SUNY) at Cortland, Cortland, NY 13045 [email protected] Abstract: Ultrasociality refers to the social organization of a few species, including humans and some social insects, having a complex division of labor, city-states, and an almost exclusive dependence on agriculture for subsistence. We argue that the driving forces in the evolution of these ultrasocial societies were economic. With the agricultural transition, species could directly produce their own food and this was such a competitive advantage that those species now dominate the planet. Once underway, this transition was propelled by the selection of within-species groups that could best capture the advantages of (1) actively managing the inputs to food production, (2) a more complex division of labor, and (3) increasing returns to larger scale and larger group size. -

Quantitative Appraisal of Non-Irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program 10-22-2018 Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota Shelby Riggs University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Agribusiness Commons, Agricultural Economics Commons, Agricultural Science Commons, Applied Mathematics Commons, Applied Statistics Commons, and the Soil Science Commons Riggs, Shelby, "Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Cropland in South Dakota" (2018). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska- Lincoln. 117. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/117 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Quantitative Appraisal of Non-irrigated Ag Land in South Dakota An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska – Lincoln By Shelby Riggs, BS Agricultural Economics College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources October 22nd, 2018 Faculty Mentor: Jeffrey Stokes, PhD, Agricultural Economics Abstract This appraisal attempts to remove subjectivity from the appraisal process and replace it with quantitative analysis of known data to generate fair market value the subject property. Two methods of appraisal will be used, the income approach and the sales comparison approach. For the income approach, I use the average cash rent for the region, the current property taxes for the subject property, and a capitalization rate based on Stokes’ (2018) capitalization rate formula to arrive at my income-based valuation. -

Switchgrass – Reprinted from Friends of Hagerman NWR Weekly Blog, December 14, 2017 (Written by Linn Cates)

Switchgrass – Reprinted from Friends of Hagerman NWR Weekly Blog, December 14, 2017 (Written by Linn Cates) Switchgrass, Panicum virgatum, is a fast-growing, tall, warm weather perennial grass. It forms large, open, feathery looking, finely textured seed heads that transform it from a pleasing, but plainer look, (while the nearby spring and summer flowers demand the limelight) to an impressive, dressy fall showing. This continues, though somewhat subdued, right through the winter, until mid-spring when things warm up and a whole new chorus of green leaves emerge from the switchgrass crown to begin the show anew. Native to the North American prairie, switchgrass’s large range is east of the Rocky Mountains (south of latitude 55°N,) from Canada south through the United States and into Mexico. In Texas, it grows in all regions (below left in Comfort, TX) but is rare in the Trans-Pecos area of west Texas. In our part of Texas, North Central, you can see it at Clymer Meadow (above right), a large prairie remnant nearby in Hunt County, in native haying meadows near St. Jo in Montague County, at Austin College’s Sneed property in Grayson County, and at Hagerman National Wildlife Refuge among other places. But you could see it easily and up close by driving out to Hagerman NWR Visitor Center and taking a look in the Butterfly Garden right behind the parking area. You won’t miss it; one of the garden’s switchgrass specimens (below) has a plaque hanging in front of it, identifying it as “Switchgrass, Plant of the Month.” The repertoire of this performer, Panicum virgatum, is extensive. -

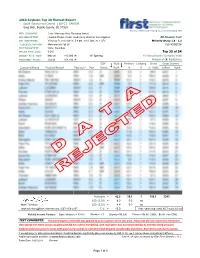

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report Top 30 of 54

2018 Soybean Top 30 Harvest Report South Dakota East Central [ SDEC ] CAVOUR Greg Bich, Beadle County, SD 57324 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC, New Richland, MN PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Harness Xtra, Roundup (twice) SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non-irrigated All-Season Test SOIL CONDITIONS: Very low P, very high K, 5.9 pH, 3.0% OM, 20.1 CEC Maturity Group 1.6 - 2.3 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Minimum w/o fall till S2018SDEC06 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup APPLIED N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 Top 30 of 54 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: May 26 140,000 /A 30" Spacing For Gross Income (Sorted by Yield) HARVESTED - STAND: Oct 23 108,100 /A Average of (2) Replications SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand†Technol.† Mat. Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank Averages = 42.8 10.1 1 108.1 $343 LSD (0.10) = 8.3 0.5 ns Mark Tollefson LSD (0.25) = 4.4 0.3 ns [email protected], (507) 456-2357 C.V. = 15.0 Prev. years avg. yield, 45.7 bu/a, 10 yrs Yield & Income Factors: Base Moisture = 13.0% Shrink = 1.3 Drying = $0.020 Prices = $8.00 GMO; $8.00 non-GMO TEST COMMENTS: The preemergence herbicide was applied to only a portion of the test area. Areas that did not receive this treatment were weedy the entire season as glphosate did not control everything. One replication was not harvested due to extreme weed pressure. Soybean yield was great in areas with good weed control (1 replication) but dropped considerably elsewhere. -

Prairie Restoration Technical Guides

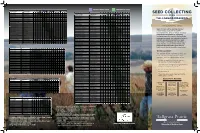

Optimal Collection Period Seed Ripening Period EARLY SEASON NATIVE FORBS May June July August September EARLY SEASON NATIVE FORBS May June July August SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 Caltha palustris Marsh marigold LATE SEASON NATIVE FORBS August September October November SEED COLLECTING Prairie smoke SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 1-10 10-20 20-30 FROM Antennaria neglecta Pussytoes Stachys palustris Woundwort Castilleja coccinea Indian paintbrush Vicia americana Vetch False dandelion Rudbeckia hirta Black-eyed Susan TALLGRASS PRAIRIES Saxifraga pensylvanica Swamp saxifrage Lobelia spicata Spiked lobelia Senecio aureus Golden ragwort Iris shrevei Sisyrinchium campestre Blue-eyed grass Hypoxis hirsuta Yellow star grass Rosa carolina Pasture rose Content by Greg Houseal Pedicularis canadensis Lousewort Oxypolis rigidior Cowbane PRAIRIE RESTORATION SERIES V Prairie violet Vernonia fasciculata Ironweed Cardamine bulbosa Spring cress Veronicastrum virginicum Culver's root Allium canadense Wild garlic Heliopsis helianthoides Seed of many native species are now Lithospermum canescens Hoary puccoon L Narrow-leaved loosestrife commercially1 available for prairie Phlox maculata Marsh phlox Lythrum alatum Winged loosestrife Phlox pilosa Prairie phlox reconstructions, large or small. Yet many Ceanothus americana New Jersey tea Anemone canadensis Canada anemone Eupatorium maculatum Spotted Joe Pye people have an interest in collecting Prunella vulgaris var. -

Selected Qualitative Parameters Above-Ground Phytomass of the Lenor-First Slovak Cultivar of Festulolium A

Acta fytotechn zootechn, 22, 2019(1): 13–16 http://www.acta.fapz.uniag.sk Original Paper Selected qualitative parameters above-ground phytomass of the Lenor-first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A. et Gr. Peter Hric*, Ľuboš Vozár, Peter Kovár Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra, Slovak Republic Article Details: Received: 2018-10-04 | Accepted: 2018-11-06 | Available online: 2019-01-31 https://doi.org/10.15414/afz.2019.22.01.13-16 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License The aim of this experiment was to compare selected qualitative parameters in above-ground phytomass of the first Slovak cultivar of Festulolium A et. Gr. cv. Lenor in comparison to earlier registered cultivars Felina and Hykor. The pot experiment was conducted at the Demonstrating and Research base of the Department of Grassland Ecosystems and Forage Crops, Slovak Agricultural University in Nitra (Slovak Republic) with controlled moisture conditions (shelter) in 2017. Content of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, crude fibre and water soluble carbohydrates were determined from dry above-ground phytomass of grasses. The significantly highest (P <0.05) nitrogen content in average of cuts was in above-ground phytomass of Felina (30.3 g kg-1) compared to Hykor (25.4 g kg-1) and new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (25.0 g kg-1). The lowest phosphorus content was found out in hybrid Lenor (3.4 g kg-1). In average of three cuts, the lowest concentration of potassium was in new intergeneric hybrid Lenor (5.8 g kg-1). The lowest content of calcium was found out in hybrid Lenor (7.0 g kg-1). -

Restoring the Prairie

Restoring the Prairie Grade: 3rd Season: Winter Time: 1 ½ hours Group Size: 1 class Ratio: 1:5 (adult: children) For the Teacher: Overview Students design an investigation about prairie restoration driven by their own questions. They participate directly in restoring the prairie by planting seeds in the prairie. (If possible, they may also be able to make observations of seedlings in the greenhouse and/or plant seeds there.) Lastly, they reflect upon their discoveries and answer their investigation questions. Subjects Covered Science MN Academic Helps support 17 standards. See section “2009 Minnesota Academic Standards Standards Supported in Science” and “2010 Minnesota Academic Standards in Language Arts.” Skills Used Investigating, following directions, listening, cooperating, asking and answering questions, observing, describing, measuring, sketching, reflecting, concluding, magnifying, collecting data, analyzing data, restoring habitat, thinking critically, writing, examining, discovering, teamwork, organizing Performance After completing this activity, students will be better able to… Objectives Identify two methods of prairie restoration (sowing in the field, sowing in the greenhouse and planting seedlings in the field) Name two kinds of prairie plants (grasses and forbs) Name at least one prairie plant species Plant prairie seeds in the field Explain why people restore prairie Enjoy making a difference improving the health of the prairie Vocabulary Investigate, prairie, restore, seedling, greenhouse, seeding/sowing, grass, forb, germinate, sowing For the PWLC Instructor: PWLC Theme The Prairie Pothole Region Primary EE Message The prairie pothole region is valuable and in need of restoration and protection. Sub-message People: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service works with others to preserve, manage, and restore prairie wetlands in the prairie pothole region. -

Prairie Reconstruction DRS CAROLYN GRYGIEL, JACK NORLAND and MARIO BIONDINI

© LINDA NORLAND Prairie reconstruction AND MARIO BIONDINI NORLAND JACK GRYGIEL, CAROLYN DRS Professor Emeritus and former Director of Natural Resources Management at North Dakota State University, Dr Carolyn Grygiel and her colleagues Drs Jack Norland and Mario Biondini are at the forefront of new methods for redressing the lost biodiversity of grasslands Firstly, as Director of Natural Resources to be pushing vegetation changes at the Are herbicides Management (NRM), how did you support landscape level. This new perspective led me or rototilling the faculty and student body in their to the concept of ‘patch dynamics’, which traditional management endeavours? would eventually focus on the impacts of options? Can they be applied small-scale disturbances as a model for sustainably? CG: While I was Director my main focus prairie reconstruction. was working with the undergraduate Herbicide application/drill seeding and and graduate students, inspiring them Is it feasible to ‘rewild’ these environments? rototilling/broadcast seeding are conventional to take the ‘long-term decision’ and ask Why must they be managed as prairie land? methods that take an agronomic, ie. farming, the ‘next big question.’ As is customary approach to restoring a natural system. While with interdisciplinary programmes, NRM Prairie reconstruction is feasible. Our both of these methods may prove initially was primarily dependent upon other research has shown that the installation effective, they are not generally sustainable departmental cohorts to provide our of small-scale disturbances and proper in that the forb component diminishes within graduate students with research projects seed mixtures can sustainably enhance a few years. We contend that the success and stipends. -

Woody-Invaded Prairie to Utility Prairie

Restoring Your Woody-Invaded Prairie to Utility Prairie The author of this Restoration Guide is Laura Phillips-Mao, University of Minnesota. Steve Chaplin, MN/ND/SD Chapter of The Nature Conservancy, administered the project and helped with production. Marybeth Block, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, provided review and editorial comments. Susan Galatowitsch, University of Minnesota, contributed to an earlier version of this guide. ©The Nature Conservancy January 1, 2017 Funding for the development of this restoration guide was provided by the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund as recommended by the Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR) through grant LCCMR092C. The Trust Fund is a permanent fund constitutionally established by the citizens of Minnesota to assist in the protection, conservation, preservation, and enhancement of the state’s air, water, land, fish, wildlife, and other natural resources. Currently 40% of net Minnesota State Lottery proceeds are dedicated to building the Trust Fund and ensuring future benefits for Minnesota’s environment and natural resources. Additional funding for the update and redesign of the guide was provided by a Working Lands Initiative grant from the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Cover photo taken at Sheepberry Fen Preserve by Alison Mickelson, Greater Good Photography. Restoring Your Woody- Why restore woody-invaded Invaded Prairie to prairies? Prairies that are not burned, grazed or mowed “Utility Prairie” are often invaded by woody trees and shrubs. In Minnesota, the prairie-forest border shifts In this guide, you will learn the basic steps to over time in response to changes in climate and restoring a degraded prairie invaded by woody fire frequency. -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota December 2012 Approved by Noreen Walsh, Regional Director Date U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Lakewood, Colorado Prepared by Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex 38672 291st Street Lake Andes, South Dakota 57356 605 /487 7603 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain–Prairie Region Division of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, Colorado 80228 303 /236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex, South Dakota. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 218 p. Comprehensive Conservation Plan Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex South Dakota Submitted by Concurred with by Michael J. Bryant Date Bernie Peterson. Date Project Leader Refuge Supervisor, Region 6 Lake Andes National Wildlife Refuge Complex U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Lake Andes, South Dakota Lakewood, Colorado Matt Hogan Date Assistant Regional Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................... XI Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................. XVII CHAPTER 1–Introduction ..................................................................... -

2019 FIRST Harvest Report

SCN Yield Moisture Lodging Stand Gross Income Company/Brand Product/Brand Technol.† RM Resist. Bu/A % % (x 1000) $/Acre Rank HEFTY H24X8 RRX 2.4 MR 58.2 15.0 1 114.2 492 1 ASGROW AG22X0 § RRX 2.2 R 57.4 14.2 6 112.3 486 2 Test by: MNS Seed Testing, LLC New Richland, MN TITAN PRO 28E8 E3 2.8 R 55.8 14.4 5 112.3 472 3 2019 Soybeans Top 30 Harvest Report HOEGEMEYER 2540 E E3 2.5 R 55.2 14.4 2 113.3 467 4 South Dakota Southeast [SDSE] SALEM, SD REA RX2518 § RRX 2.5 R 54.9 14.5 4 110.4 465 5 Ernie Christensen, McCook County, SD 57048 HOEGEMEYER 2202 NX RRX 2.2 R 54.5 14.3 4 113.3 461 6 All-Season Test 2.1 - 2.8 Day CRM REA RX2639 GC RRX 2.6 R 53.8 14.1 7 114.7 456 7 S2019SDSE04 GENESIS G2140E E3 2.1 R 53.4 14.1 5 112.3 452 8 For Gross Income Top 30 of 54 CREDENZ CZ 2550GTLL LG27 2.5 MR 53.4 14.1 2 110.4 452 9 (Sorted by Yield) Average of (3) Replications LATHAM L 2549R2X RRX 2.5 R 53.1 14.1 2 112.3 450 10 CHAMPION 25X70N RRX 2.5 R 52.9 14.2 2 111.4 448 11 PREV. CROP/HERB: Corn / Valor, Roundup GENESIS G2181GL LG27 2.2 R 52.6 14.5 1 107.4 445 12 SOIL DESCRIPTION: Houdek-Prosper loam, moderately drained, non- NK BRAND S20-J5X § RRX 2.0 R 52.4 13.9 14 108.4 444 13 irrigated HEFTY Z2300E E3 2.3 R 52.3 13.8 2 112.3 444 14 SOIL CONDITION: very high P, very high K, 5.9 NK BRAND S21-W8X § RRX 2.1 R 52.2 14.0 5 109.4 442 15 pH, 3.0% OM, 19.3 CEC STINE 25GA62 § LG27 2.5 R 52.0 14.0 2 111.3 441 16 TILLAGE/CULTIVATION: Conventional W/ Fall Till PIONEER P21A28X § RRX 2.1 R 51.7 14.1 2 105.5 438 17 PEST MANAGEMENT: Valor, Roundup, Select Max HOEGEMEYER 2820 E E3 2.8 R 51.4 15.1 5 112.3 434 18 Applied N-P-K (units): 0-0-0 HEFTY Z2700E E3 2.7 R 51.3 14.7 1 113.3 434 19 SEEDED - RATE - ROW: Jun 12 140.0 /A 30" spacing LATHAM L 2395 LLGT27 LG27 2.3 R 51.2 14.0 5 108.4 434 20 HARVESTED - STAND: Nov 1 111.4 /A DYNA-GRO S24XT08 RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.1 2 113.3 433 22 RENK RS248NX RRX 2.4 R 51.2 15.5 2 112.3 432 23 TEST COMMENTS: RENK RS250NX RRX 2.5 R 51.2 14.1 1 112.3 434 21 This was a clean field with a fairly consistent stand of HEFTY H25X0 RRX 2.5 R 50.9 14.3 2 113.3 431 24 soybeans. -

Nine-Mile Prairie I

The Legacy of Nine-Mile Prairie I. Brief History II. Ecological Changes III. Environmental Changes IV. Changing Perspectives on Tallgrass Prairie Conservation John E. Weaver V. The Future of Nine-Mile Prairie (1884-1966) 1857: GLO Survey of 9MP – “The surface is of high rolling prairie”, no trees were noted. Bison and fire soon disappeared. 1885: Charles Bessey arrives at UNL 1898: Frederic Clements receives PhD UNL Early 1900’s: 9MP owned by the Flader family (west half), and the McManaman family (east half). Most of the area hayed annually. 1909: John E. Weaver receives BS UNL 1915: J.E. Weaver new Professor at UNL 1927-1928: First ecological descriptions for “800 acres of treeless, unbroken prairie” by T.L. Steiger, a PhD student of Weaver (published 1930) 1934: J.E. Weaver publishes “The Prairie” in State Historic Marker honoring Ecological Monographs (one of >100 publications) J.E. Weaver, post-storm 2017 1930’s: Drought and Dust Bowl 1949 1941: Professor Frank purchases eastern half of 9MP 1944: F.W. Albertson & J.E. Weaver publish “Nature & degree of recovery of grassland from the Great Drought 1933-1940” 1952: Weaver retires 1966: Weaver dies 1950: US Air Force takes over 9MP & surrounding area to support a Strategic Air Command Base (1952-1966). 1970’s: Lincoln Airport Authority acquires 9MP & Air Park. 9MP is rented by Ernie Rousek on behalf of Wachiska Audubon. 1981: Legislative Act (Bill 58) encourages LAA to protect 9MP (R.B. Crosby, E. Rousek, A.T. Harrison) 1984: NU Foundation purchases Nine-Mile Prairie (donation by Marguerite Hall) 2001: Michael Forsberg’s 9MP photo released as US postage stamp.