Chapter 2: Area Description And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

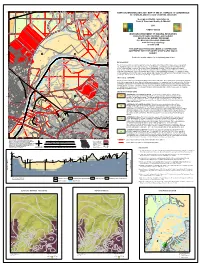

ST. CHARLES 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qslt 0 5 4 ST

90°22'30"W 90°30'00"W 90°27'30"W 90°25'00"W R 5 E R 6 E 38°52'30"N 38°52'30"N 31 32 33 34 35 36 31 35 SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE ST. CHARLES 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qslt 0 5 4 ST. CHARLES AND ST. LOUIS COUNTIES, MISSOURI 0 45 Qslt 2 Geology and Digital Compilation by 0 45 Qtd David A. Gaunt and Bradley A. Mitchell Qcly «¬94 3 5 6 5 4 2011 Qslt Qtd Qtd Qtd 1 Graus «¬94 Lake OFM-11-593-GS 6 «¬H Qtd 6 Croche 9 10 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 8 7 s DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND LAND SURVEY ai ar 7 M GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROGRAM Qslt Qtd P.O. BOX 250, ROLLA MO 65402-0250 12 www.dnr.mo.gov/geology B «¬ Qslt 573-368-2100 7 13 THIS MAP WAS PRODUCED UNDER A COOPERATIVE 0 5 AGREEMENT WITH THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL 4 18 38°50'00"N 38°50'00"N SURVEY Qtd Permission must be obtained to visit privately owned land Qslt Qslt PHYSIOGRAPHY 0 5 4 St. Charles County D St. Louis County The St. Charles quadrangle includes part of the large floodplain of the Missouri River and loess covered uplands. N 500 550 A L The floodplain is up to five miles wide in this area. The quadrangle lies within the Dissected Till Plains Section 50 S 5 I 45 6 0 0 0 of the Central Lowland Province of the Interior Plains Physiographic Division. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

APPENDIX 18. Iowa Lakes and Rivers by Region

APPENDIX 18. Iowa Lakes and Rivers by Region Region Locator Map 329 Map 18-1. Des Moines Lobe - Lakes and Rivers 330 Map 18-2. Iowan Surface - Lakes and Rivers 331 Map 18-3. Loess Hills - Lakes and Rivers 332 Map 18-4. Mississippi Alluvial Plain - Lakes and Rivers 333 Map 18-5. Missouri Alluvial Plain - Lakes and Rivers 334 Map 18-6. Northwest Iowa Plains - Lakes and Rivers 335 Map 18-7. Prairie to Hardwood Transition - Lakes and Rivers 336 Map 18-8. Southern Iowa Drift Plain - Lakes and Rivers 337 APPENDIX 19. Existing Large Habitat Complexes in Public Ownership by Region – Updated in 2010 Region Locator Map 338 Map 19-1. Iowan Surface - Large Habitat Complexes 339 Map 19-2. Des Moines Lobe - Large Habitat Complexes 340 Map. 19-3. Loess Hills - Large Habitat Complexes 341 Map 19-4. Mississippi Alluvial Plain - Large Habitat Complexes 342 Map. 19-5. Missouri Alluvial Plain - Large Habitat Complexes 343 Map 19-6. Northwest Iowa Plains - Large Habitat Complexes 344 Map 19-7. Paleozoic Plateau Large Habitat Complexes 345 Map 19-8. Southern Iowa Drift Plain - Large Habitat Complexes 346 APPENDIX 20. References Cited and Used in Document Preparation ARBUCKLE, K.E. and J.A. DOWNING. 2000. Statewide assessment of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia, Unionidae) in Iowa streams . Final Report to the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Des Moines, IA. BISHOP, R.A. 1981. Iowa's Wetlands . Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 88(1):11-16. BISHOP, R.A., J. JOENS, J. ZOHRER. 1998. Iowa's Wetlands, Present and Future with a Focus on Prairie Potholes . -

Wildlife CONSERVATION Vantage Point Working to Conserve All Wildlife

October 2005 Volume 66 MISSOURI Issue 10 CONSERVATIONISTServing Nature & You Special Issue All Wildlife CONSERVATION Vantage Point Working to Conserve All Wildlife his edition of the Conservationist is devoted to the theme of “All Wildlife Conservation.” It highlights a renewed Department focus to conserve a broad Tarray of wildlife and plants in recognition that all living things are part of a complex system. I first learned the phrase “web of life” in high school at about the same time I watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon! Our biology class took a field trip to Peck Ranch Conservation Area to observe Conservation Department efforts to restore wild turkey in Missouri. In those days, Peck Ranch was a wildlife refuge man- Ornithologist Andy Forbes (right) guides Director John aged for turkeys and other species used to stock areas of Hoskins on a birdwatch near Jefferson City. the state where population restoration was thought pos- sible. The busy refuge manager, Willard Coen, explained landscape changes are not clearly understood, but we the type of vegetation turkeys preferred and showed us do know that addressing them is an essential part of the cannon-net technique he used to trap the live birds. any effective action plan. He topped the trip off by showing a Department movie Fortunately, conservation employees do not face called “Return of the Wild Turkey” created by Glenn these challenges alone. Many partners are committed Chambers, and Elizabeth and Charles Schwartz. to sharing resources and achieving common goals. Obviously, that field trip over thirty years ago left an First and foremost, individual landowners are impression about the management of turkeys. -

A Preliminary Survey of the Bird Life of North Dakota

UNIVERSITY OP MICHIGAN MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY Miscellaneous Publications No. 10 A Preliminary Survey of the Bird Life of North Dakota BY NORMAN A. WOOD ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY JULY 2, 1923 OUTLINE MAP OF NORTH DAKOTA UNIVERSI'rY OF hlICHIGAN MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY Miscellaneous Publications No. 10 A Preliminary Survey of the Bird Life of North Dakota RY NORMAN A. WOOD ANN ARBOR, MICIIIGAN PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY JULY 2, I923 The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigart, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous PubK- cations. Both series were founded bv Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradsl~aw I-I. Swales and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, j-rve as a medium for the publication of brief oriqinal papers based principally upon the collections in the Museum. The papers are issued separately to libraries and specialists, and, when a sufficient nu~uberof pages have l~crn printed to make a volume, a title page, index, and table of contents are sup- plied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the entire series. The Miscellaneous Publications include papers on field and museum technique, monographic studies and other papers not within the scope of the Occasional Papers. The papers are published separately, and, as it is not intended that they shall be grouped into volumes, each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. ALEXANDERG. RUTHITEN, Director of the Museum of Zoology, [Jniversity ~f Michigan. A PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF THE BIRD LIFE OF NORTH DAKOTA The field studies upon which this paper is largely based were carried on during the summers of 1920 and 1921. -

GEOLOGY and GROUND WATER RESOURCE S of Stutsman County, North Dakota

North Dakota Geological Survey WILSON M. LAIRD, State Geologis t BULLETIN 41 North Dakota State Water Conservation Commission MILO W . HOISVEEN, State Engineer COUNTY GROUND WATER STUDIES 2 GEOLOGY AND GROUND WATER RESOURCE S of Stutsman County, North Dakota Part I - GEOLOG Y By HAROLD A. WINTERS GRAND FORKS, NORTH DAKOTA 1963 This is one of a series of county reports which wil l be published cooperatively by the North Dakota Geological Survey and the North Dakota State Water Conservation Commission in three parts . Part I is concerned with geology, Part II, basic data which includes information on existing well s and test drilling, and Part III which will be a study of hydrology in the county . Parts II and III will be published later and will be distributed a s soon as possible . CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 3 Acknowledgments 3 Previous work 5 GEOGRAPHY 5 Topography and drainage 5 Climate 7 Soils and vegetation 9 SUMMARY OF THE PRE-PLEISTOCENE STRATIGRAPHY 9 Precambrian 1 1 Paleozoic 1 1 Mesozoic 1 1 PREGLACIAL SURFICIAL GEOLOGY 12 Niobrara Shale 1 2 Pierre Shale 1 2 Fox Hills Sandstone 1 4 Fox Hills problem 1 4 BEDROCK TOPOGRAPHY 1 4 Bedrock highs 1 5 Intermediate bedrock surface 1 5 Bedrock valleys 1 5 GLACIATION OF' NORTH DAKOTA — A GENERAL STATEMENT 1 7 PLEISTOCENE SEDIMENTS AND THEIR ASSOCIATED LANDFORMS 1 8 Till 1 8 Landforms associated with till 1 8 Glaciofluvial :materials 22 Ice-contact glaciofluvial sediments 2 2 Landforms associated with ice-contact glaciofluvial sediments 2 2 Proglacial fluvial sediments 2 3 Landforms associated with proglacial fluvial sediments 2 3 Lacustrine sediments 2 3 Landforms associated with lacustrine sediments 2 3 Other postglacial sediments 2 4 ANALYSIS OF THE SURFICIAL TILL IN STUTSMAN COUNTY 2 4 Leaching and caliche 24 Oxidation 2 4 Stone counts 2 5 Lignite within till 2 7 Grain-size analyses of till _ 2 8 Till samples from hummocky stagnation moraine 2 8 Till samples from the Millarton, Eldridge, Buchanan and Grace Cit y moraines and their associated landforms _ . -

Chapter 3, District Resources and Description

CHAPTER 3— District Resources and Description Bridgette Flanders-Wanner / USFWS / Bridgette Flanders-Wanner Grasslands in the Millerdale Waterfowl Production Area. The three wetland management districts manage smaller temporary and seasonal wetlands that draw thousands of noncontiguous tracts of Federal land breeding duck pairs to South Dakota and other parts totaling 1,136,965 acres: 100,094 acres of WPAs and of the Prairie Pothole Region. 1,036,871 acres of conservation easements. This chap ter describes the physical environment and biological CLIMATE CHANGE resources of these district lands, as well as fire and In January 2001, the Department of the Interior is grazing history, cultural resources, visitor services, sued Order 3226, requiring its Federal agencies with socioeconomic environment, and district operations. land management responsibilities to consider potential climate change effects as part of long-range planning endeavors. The U.S. Department of Energy’s report, “Carbon Sequestration Research and Development,” 3.1 Physical Environment concluded that ecosystem protection is important to carbon sequestration and may reduce or prevent loss The districts are located in central and eastern South of carbon currently stored in the terrestrial biosphere. Dakota from west of the Missouri River to the Minnesota The report defines carbon sequestration as “the capture state line, and from the North Dakota border roughly and secure storage of carbon that would otherwise be two-thirds of the way south to the state line of Nebraska. emitted to or remain in the atmosphere.” The increase The prairies of South Dakota have become an eco of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the earth’s atmosphere has logical treasure of biological importance for water been linked to the gradual rise in surface temperature fowl and other migratory birds. -

SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP of the KIRKWOOD 7.5' QUADRANGLE Ql R 0 6 Ql 65 50

90°30'00"W 90°27'30"W 90°25'00"W 90°22'30"W R 5 E R 6 E 38°37'30"N D 38°37'30"N 0 e 5 60 e 6 0 r 0 19 20 21 22 23 65 24 600 19 C SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE KIRKWOOD 7.5' QUADRANGLE Ql r 0 6 Ql 65 50 6 5 0 500 ST. LOUIS AND JEFFERSON COUNTIES, MISSOURI 0 650 0 650 0 Ql k T w 6 5 o m Qa 0 5 i l e 5 C 5 Ql r e e k £67 5 ¤ Frontenac 600 0 LADUE 5 0 50 0 R 650 5 5 5 60 0 5 6 0 0 00 0 6 600 Geology and Digital Compilation by Huntleigh 60 0 0 5 0 600 6 0 0 Ql 0 6 5 6 50 550 0 Bradley A. Mitchell 0 Qa «¬JJ k 6 0 Town and Country 0 0 0 0 5 6 650 0 5 5 5 5 600 5 500 5 600 0 0 0 0 5 R k 0 5 0 6 5 6 5 Pb 0 28 0 0 0 5 Ql 27 6 26 Ql 5 2012 0 0 65 Des Peres 6 0 25 0 0 0 Rock Hill 0 5 6 0 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 0 6 0 6 30 0 30 0 0 Warson Woods 29 0 6 0 6 60 50 5 0 29 0 6 OFM-12-615-GS 5 0 500 0 00 0 6 0 0 5 5 5 5 5 550 Ql 6 0 k 0 Pb Pb 0 5 6 5 5 R 00 R 5Ql 50 0 R 0 5 0 6 0 5 6 5 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 0 5 0 6 Ql 0 0 R Pb 0 0 0 5 5 0 5 550 6 6 0 Qa 0 DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND LAND SURVEY 0 6 0 0 100 5 0 0 0 5 6 ¬ 0 « 0 550 5 6 0 32 R 6 0 0 0 0 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROGRAM 0 5 5 34 0 6 Ql 0 0 65 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 5 36 32 5 6 0 0 0 100 6 33 6 5 0 «¬ 5 600 6 35 6 0 0 55 Ql 31 50 0 P.O. -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Huron Wetland Management District Madison Wetland Management District Sand Lake Wetland Management District South Dakota

Comprehensive Conservation Plan Huron Wetland Management District Madison Wetland Management District Sand Lake Wetland Management District South Dakota January 2012 Approved by Stephen D. Guertin, Regional Director Date U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Lakewood, Colorado Prepared by Huron Wetland Management District Room 309 Federal Building 200 Fourth Street SW. Huron, South Dakota 57350 605 / 352 5894 Madison Wetland Management District 23520 SD Highway 19 Madison, South Dakota 57042 605 / 256 2974 Sand Lake Wetland Management District 39650 Sand Lake Drive Columbia, South Dakota 57433 605 / 885 6320 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 6, Mountain–Prairie Region Division of Refuge Planning 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 300 Lakewood, Colorado 80228 303 / 236 8145 CITATION for this document: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2012. Comprehensive conservation plan: Huron Wetland Management District, Madison Wetland Management District, and Sand Lake Wetland Management District, South Dakota. Lakewood, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 260 p. Comprehensive Conservation Plan Huron Wetland Management District Madison Wetland Management District Sand Lake Wetland Management District South Dakota Submitted by Concurred with by Clarke Dirks Date Richard A. Coleman, Ph.D. Date Project Leader Assistant Regional Director Huron Wetland Management District U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Huron, South Dakota National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Natoma Buskness Date Paul Cornes Date Project Leader Refuge Supervisor Madison Wetland Management District U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 Madison, South Dakota National Wildlife Refuge System Lakewood, Colorado Harris Hoistad Date Project Leader Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge Complex Columbia, South Dakota Contents Summary ..................................................................................... -

North Dakota State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Peace Garden State

North Dakota State Research Guide Family History Sources in the Peace Garden State North Dakota History The first Europeans in the area arrived the last part of the eighteenth century and were fur traders employed by the Missouri Fur Company. The peopling of the area quickly followed the first exploration with settlements in Selkirk Colony, on the Red and Assiniboine rivers, and the Pembina settlement. Both were established in 1812, but conditions were so difficult that by 1823 Selkirk had become part of the Hudson Bay Company settlement and Pembina had been abandoned. The indigenous tribes of the Dakotas were the Mandans and Arikaras. Eastern tribes that were moved into the area included Hidatsas, Crows, Cheyennes, Creeks, Assiniboines, Yanktonai Dakotas, Teton Dakotas, and Chippewas. The smallpox epidemics in 1782 and 1786 wiped out three-fourths of the Mandans and half of the Hidatsas. The epidemic of 1837, probably introduced by the white fur traders, also had a devastating effect on the native population. Composing the largest settlement at the Red River were the “half-breeds” (called métis) who were the offspring of European fathers (French, Canadian, Scottish, and English) and Native American mothers (Chippewa, Creek, Assiniboine). Many area residents claimed French-Chippewa ancestry. By 1850 more than half of the five to six thousand people living at Fort Garry were métis, with a large percentage being Canadian- born. Settlers began moving into the region in 1849 with the organization of Minnesota Territory and the settlement of Iowa and Minnesota. This immigration brought a number of settlers to southeastern Dakota. Dakota Territory was created by an act of Congress on 2 March 1861 from the area that had previously been Nebraska and Minnesota territories. -

Influence of Natural Factors on the Quality of Midwestern Streams and Rivers

Influence of Natural Factors on the Quality of Midwestern Streams and Rivers —Stephen D. Porter, Mitchell A. Harris, and Stephen J. Kalkhoff Streams flowing through cropland in the Midwestern Corn Belt differ considerably in their chemical and ecological characteristics, even though agricultural land use is highly intensive throughout the entire region. These differences likely are attributable to differences in riparian vegetation, soil properties, and hydrology. This conclusion is based on results from a study of the upper Contents Midwest region conducted during seasonally low-flow conditions in Introduction. 1 August 1997 by the U.S. Geological Natural Factors Influence Chemical Indicators Survey (USGS) National Water of Water Quality . 4 Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Natural Factors Influence Biological Indicators Program. This report summarizes of Water Quality . 8 significant results from the study and presents some implications for the Implications for Water-Quality Monitoring and design and interpretation of water- Assessment . 12 quality monitoring and assessment References Cited . 13 studies based on these results. Introduction The U.S. Geological Survey percentage of trees in buffer zones (USGS) National Water-Quality along riparian segments. Census data The Midwestern Corn Belt is Assessment (NAWQA) Program from the U.S. Department of Agri- one of the most productive agricul- conducted a water-quality study in culture (USDA) for 1997 were used tural regions in the world. Nearly the upper Midwest region during in this study to quantify cropland, 80 percent of the Nation’s corn and seasonally low-flow conditions in livestock, and chemical application soybeans is grown in the region. August 1997. Chemical and biologi- in each basin. -

Minnehaha County, South Dakota and Incorporated Areas

MINNEHAHA COUNTY, SOUTH DAKOTA AND INCORPORATED AREAS Community Community Name Number BALTIC, TOWN OF 460058 BRANDON, CITY OF 460296 *COLTON, CITY OF 460166 *CROOKS, CITY OF 460314 DELL RAPIDS, CITY OF 460059 GARRETSON, CITY OF 460177 HARTFORD, CITY OF 460180 HUMBOLDT, TOWN OF 460118 MINNEHAHA COUNTY, SD UNINCORPORATED AREAS 460057 *SHERMAN, TOWN OF 460313 SIOUX FALLS, CITY OF 460060 VALLEY SPRINGS, CITY OF 460221 *Non-Floodprone Community REVISED: NOVEMBER 16, 2011 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 46099CV000B NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this FIS may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map (FBFM) panels (e.g., floodways, cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows: Old Zone(s) New Zone A1 through A30 AE B X C X Initial Countywide FIS Report Effective Date: September 2, 2009 Revised Countywide FIS Report Date: November 16, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................