Wildlife CONSERVATION Vantage Point Working to Conserve All Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flyer200206 Parent

THE, FLYE, R Volume 26,25, NumberNumber 6 6 tuneJune 20022002 NEXT MEETING After scientists declared the Gunnison Sage Grouse a new species two years ago, a wide spot on Gun- Summer is here and we won't have meeting until a nison County (Colorado) Road 887, has become an Wednesday, 18. It begin September will atl:30 international bird-watching sensation. Birders from p.m. in Room 117 Millington Hall, on the William around the ,world wait silently in the cold dark of a campus. The editors'also get a summer &Mary Colorado spring pre-dawn to hear the "Thwoomp! vacation so there will be no July Flyer, but "God Thwoomp! Thwoomp!" of a male Gunnison Sage the creek rise," there be an willing and if don't will Grouse preparing to mate. The noise comes from August issue. specialized air sacs on the bird's chest. And this is now one stop on a well-traveled 1,000 mile circuit being traveled by birders wanting to add this Gun- RAIN CURTAILS FIELD TRIP TO nison bird, plus the Chukar, the Greater Sage YORK RIVER STATE PARK Grouse, the White-tailed Ptarmigan, the Greater Chicken Skies were threatening and the wind was fierce at Prairie and the Lesser Prairie Chicken to the beginning of the trip to the York River State their lii'e lists. Park on May 18. Despite all of that, leader Tom It was not always like this. Prior to the two-year- Armour found some very nice birds before the rains ago decision by the Ornithological Union that this came flooding down. -

Breeding Ecology of Barred Owls in the Central Appalachians

BREEDING ECOLOGY OF BARRED OWLS IN THE CENTRAL APPALACHIANS ABSTRACT- Eight pairs of breedingBarred Owls (Strix varia) in westernMaryland were studied. Nest site habitat was sampledand quantifiedusing a modificationof theJames and Shugart(1970) technique (see Titus and Mosher1981). Statisticalcomparison to 76 randomhabitat plots showed nest sites werb in moremature forest stands and closer to forest openings.There was no apparent association of nestsites with water. Cavity dimensions were compared statistically with 41 randomlyselected cavities. Except for cavityheight, there were no statistically significant differences between them. Smallmammals comprised 65.9% of the totalnumber of prey itemsrecorded, of which81.5% were members of the familiesCricetidae and Soricidae. Birds accounted for 14.6%of theprey items and crayfish and insects 19.5%. We also recordedan apparentinstance of juvenile cannibalism. Thirteennestlings were produced in 7 nests,averaging 1.9 young per nest.Only 2 of 5 nests,where the outcome was known,fledged young. The Barred Owl (Strix varia) is a common noc- STUDY AREA AND METHODS turnal raptor in forestsof the easternUnited States, The studywas conducted in Green Ridge State Forest (GRSF), though few detailedstudies of it havebeen pub- Allegany County, Maryland. It is within the Ridge and Valley lished.Most reportsare of singlenesting occurr- physiographicregion (Stoneand Matthews 1977), characterized by narrowmountain ridges oriented northeast to southwestsepa- encesand general observations(Bolles 1890; Carter rated by steepnarrow valleys(see Titus 1980). 1925; Henderson 1933; Robertson 1959; Brown About 74% of the countyand nearly all of GRSF is forested 1962; Caldwell 1972; Hamerstrom1973; Appel- Major foresttypes were describedby Brushet al. (1980).Predom- gate 1975; Soucy 1976; Bird and Wright 1977; inant tree speciesinclude white oak (Quercusalba), red oak (Q. -

Scarlet Tanager Piranga Olivacea

Scarlet Tanager Piranga olivacea In most Ohio counties, Scarlets are the most numerous residents north through Hocking, Athens, and Washington resident tanager. While they are outnumbered by Summer counties, and as fairly common along the remainder of the Tanagers in a few counties bordering the Ohio River, especially plateau (Hicks 1937). During subsequent decades, local declines Lawrence, Scioto, and Adams counties as well as the Cincinnati have been evident in the farmlands of western and central Ohio area (Kemsies and Randle 1953, Peterjohn 1989a), Scarlets easily where agricultural activities have eliminated most suitable predominate in the remainder of the state. Based on Breeding woodlands. Conversely, reforestation has allowed their numbers Bird Survey data, Scarlets are most numerous along the entire to expand within the unglaciated counties (Peterjohn 1989a). In Allegheny Plateau while fewer are found elsewhere. This pattern fact, Breeding Bird Surveys indicated Scarlet Tanagers were of relative abundance reflects the widespread availability of increasing within Ohio and throughout the Great Lakes region suitable woodlands along the plateau contrasted with the more between 1965 and 1979 (Robbins, C. S., et al. 1986). local distribution of these habitats in the other counties. Breeding Scarlet Tanagers occupy the canopies of mature deciduous woodlands. At Buckeye Lake, Trautman (1940) claimed they preferred beech–oak–maple woods rather than swamp forests. In the Cleveland area, however, Williams (1950) found breeding pairs in every woodland community including wooded residential areas. Their widespread distribution during the Atlas Project also indicated these tanagers occupy most deciduous woodland communities. Breeding pairs definitely prefer mature forests with closed canopies. -

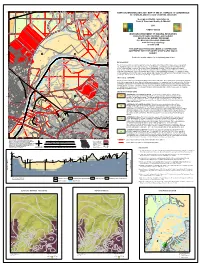

ST. CHARLES 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qslt 0 5 4 ST

90°22'30"W 90°30'00"W 90°27'30"W 90°25'00"W R 5 E R 6 E 38°52'30"N 38°52'30"N 31 32 33 34 35 36 31 35 SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE ST. CHARLES 7.5' QUADRANGLE Qslt 0 5 4 ST. CHARLES AND ST. LOUIS COUNTIES, MISSOURI 0 45 Qslt 2 Geology and Digital Compilation by 0 45 Qtd David A. Gaunt and Bradley A. Mitchell Qcly «¬94 3 5 6 5 4 2011 Qslt Qtd Qtd Qtd 1 Graus «¬94 Lake OFM-11-593-GS 6 «¬H Qtd 6 Croche 9 10 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 8 7 s DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND LAND SURVEY ai ar 7 M GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROGRAM Qslt Qtd P.O. BOX 250, ROLLA MO 65402-0250 12 www.dnr.mo.gov/geology B «¬ Qslt 573-368-2100 7 13 THIS MAP WAS PRODUCED UNDER A COOPERATIVE 0 5 AGREEMENT WITH THE UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL 4 18 38°50'00"N 38°50'00"N SURVEY Qtd Permission must be obtained to visit privately owned land Qslt Qslt PHYSIOGRAPHY 0 5 4 St. Charles County D St. Louis County The St. Charles quadrangle includes part of the large floodplain of the Missouri River and loess covered uplands. N 500 550 A L The floodplain is up to five miles wide in this area. The quadrangle lies within the Dissected Till Plains Section 50 S 5 I 45 6 0 0 0 of the Central Lowland Province of the Interior Plains Physiographic Division. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

Letter from the Director Dear MRBO Members and Friends

Letter from the Director Dear MRBO members and friends, It’s been an incredibly busy and productive few months here at MRBO. We had hoped to get this newsletter out to you in June – but there were so many great opportunities to pursue, and the migration and breeding windows are so short, field work was the order of the hour, every hour! Dana Ripper Director Marshbird surveys continued throughout April – June, while spring migration monitoring lasted until the end of May, when we imme- diately phased into the Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survi- Ethan Duke vorship (MAPS) project on the prairies. This is the second year Assistant Director of the MAPS program, which we conduct on Grandfather, Paintbrush, and Ionia Ridge Conservation Areas just south of Sedalia, MO. This summer came with the exciting ad- Board of Directors dition of surveys on the Missouri Department of Conservation’s Mora and Hi-Lonesome prairies, which represents a unique opportunity to follow up with management evalu- Seth Gallagher ation first started in 2006. As all of these prairies undergo restoration and intensive management by the MDC; we at MRBO have the pleasure of assessing bird response to Chairman these habitat changes. Lynn Schaffer Another exciting opportunity arose late May, when we were contacted by Audubon Secretary Chicago Region. MRBO was privileged with the chance to conduct bird surveys on private grasslands in Missouri, Nebraska, and Kansas throughout the month of June. Diane Benedetti The goal of Audubon’s programs is to increase the marketability of pasture-finished beef by certifying it “Bird-Friendly” – hence the need to determine if the cattle ranches Fundraising Chair are indeed supporting prairie birds. -

APPENDIX 18. Iowa Lakes and Rivers by Region

APPENDIX 18. Iowa Lakes and Rivers by Region Region Locator Map 329 Map 18-1. Des Moines Lobe - Lakes and Rivers 330 Map 18-2. Iowan Surface - Lakes and Rivers 331 Map 18-3. Loess Hills - Lakes and Rivers 332 Map 18-4. Mississippi Alluvial Plain - Lakes and Rivers 333 Map 18-5. Missouri Alluvial Plain - Lakes and Rivers 334 Map 18-6. Northwest Iowa Plains - Lakes and Rivers 335 Map 18-7. Prairie to Hardwood Transition - Lakes and Rivers 336 Map 18-8. Southern Iowa Drift Plain - Lakes and Rivers 337 APPENDIX 19. Existing Large Habitat Complexes in Public Ownership by Region – Updated in 2010 Region Locator Map 338 Map 19-1. Iowan Surface - Large Habitat Complexes 339 Map 19-2. Des Moines Lobe - Large Habitat Complexes 340 Map. 19-3. Loess Hills - Large Habitat Complexes 341 Map 19-4. Mississippi Alluvial Plain - Large Habitat Complexes 342 Map. 19-5. Missouri Alluvial Plain - Large Habitat Complexes 343 Map 19-6. Northwest Iowa Plains - Large Habitat Complexes 344 Map 19-7. Paleozoic Plateau Large Habitat Complexes 345 Map 19-8. Southern Iowa Drift Plain - Large Habitat Complexes 346 APPENDIX 20. References Cited and Used in Document Preparation ARBUCKLE, K.E. and J.A. DOWNING. 2000. Statewide assessment of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia, Unionidae) in Iowa streams . Final Report to the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Des Moines, IA. BISHOP, R.A. 1981. Iowa's Wetlands . Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 88(1):11-16. BISHOP, R.A., J. JOENS, J. ZOHRER. 1998. Iowa's Wetlands, Present and Future with a Focus on Prairie Potholes . -

Species List, Safe Dates, and Special Species

Breeding Species List, Safe Dates, and Special Species • This list includes species that regularly, rarely, or hypothetically could breed in South Dakota. • On the Block Visit data sheet, only report observations of species from this list and within a species' safe date. • Please submit an SDOU Rare Bird Report for all species with CAPITALIZED names. Common Name AOU Code Safe Dates Common Name AOU Code Safe Dates Canada Goose CAGO 4/15 - 7/31 Red-necked Grebe RNGR 5/15 - 7/31 Trumpeter Swan TRUS 5/1 - 7/31 Eared Grebe EAGR 5/15 - 7/31 Wood Duck WODU 5/1 - 7/31 Western Grebe WEGR 5/15 - 7/31 Mallard MALL 5/1 - 7/31 Clark's Grebe CLGR 5/15 - 7/31 Northern Pintail NOPI 5/1 - 7/31 American White Pelican AWPE 5/1/ - 7/31 Common Merganser COME 5/1 - 7/31 Double-crested Cormorant DCCO 5/15 - 7/31 Gadwall GADW 5/15 - 7/31 American Bittern AMBI 5/25 - 7/31 American Wigeon AMWI 5/15 - 7/31 Least Bittern LEBI 6/1 - 7/31 American Black Duck ABDU 5/15 - 7/31 Great Blue Heron GBHE 4/15 - 7/31 Blue-winged Teal BWTE 5/15 - 7/31 Great Egret GREG 6/1 - 7/31 Cinnamon Teal CITE 5/15 - 7/31 Snowy Egret SNEG 6/1 - 7/31 Northern Shoveler NSHO 5/15 - 7/31 Little Blue Heron LBHE 6/1 - 7/31 Green-winged Teal AGWT 5/15 - 7/31 TRICOLORED HERON TRHE 6/1 - 7/31 Canvasback CANV 5/15 - 7/31 Cattle Egret CAEG 6/1 - 7/31 Redhead REDH 5/15 - 7/31 Green Heron GRHE 5/15 - 7/31 HOODED MERGANSER HOME 5/15 - 7/31 Black-crowned Night-Heron BCNH 5/15 - 7/31 Ruddy Duck RUDU 5/15 - 7/31 YELLOW-CROWNED NIGHT HERON YCNH 6/1 - 7/31 Ring-necked Duck RNDU 5/15 - 7/31 GLOSSY IBIS GLIB -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. -

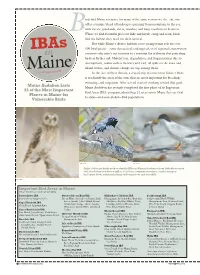

Ibastoryspring08.Pdf

irds find Maine attractive for many of the same reasons we do—the state offers a unique blend of landscapes spanning from mountains to the sea, with forests, grasslands, rivers, marshes, and long coastlines in between. B Where we find beautiful places to hike and kayak, camp and relax, birds find the habitat they need for their survival. But while Maine’s diverse habitats serve an important role for over IBAs 400 bird species—some threatened, endangered, or of regional conservation in concern—the state’s not immune to a growing list of threats that puts these birds at further risk. Habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation due to development, toxins such as mercury and lead, oil spills on the coast and Maine inland waters, and climate change are top among them. BY ANDREW COLVIN In the face of these threats, a crucial step in conserving Maine’s birds is to identify the areas of the state that are most important for breeding, wintering, and migration. After several years of working toward that goal, Maine Audubon Lists Maine Audubon has recently completed the first phase of its Important 22 of the Most Important Bird Areas (IBA) program, identifying 22 areas across Maine that are vital Places in Maine for Vulnerable Birds to state—and even global—bird populations. HANS TOOM ERIC HYNES Eight of the rare birds used to identify IBAs in Maine (clockwise from left): Short-eared owl, black-throated blue warbler, least tern, common moorhen, scarlet tanager, harlequin duck, saltmarsh sharp-tailed sparrow, and razorbill. MIKE FAHEY Important -

SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP of the KIRKWOOD 7.5' QUADRANGLE Ql R 0 6 Ql 65 50

90°30'00"W 90°27'30"W 90°25'00"W 90°22'30"W R 5 E R 6 E 38°37'30"N D 38°37'30"N 0 e 5 60 e 6 0 r 0 19 20 21 22 23 65 24 600 19 C SURFICIAL MATERIAL GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE KIRKWOOD 7.5' QUADRANGLE Ql r 0 6 Ql 65 50 6 5 0 500 ST. LOUIS AND JEFFERSON COUNTIES, MISSOURI 0 650 0 650 0 Ql k T w 6 5 o m Qa 0 5 i l e 5 C 5 Ql r e e k £67 5 ¤ Frontenac 600 0 LADUE 5 0 50 0 R 650 5 5 5 60 0 5 6 0 0 00 0 6 600 Geology and Digital Compilation by Huntleigh 60 0 0 5 0 600 6 0 0 Ql 0 6 5 6 50 550 0 Bradley A. Mitchell 0 Qa «¬JJ k 6 0 Town and Country 0 0 0 0 5 6 650 0 5 5 5 5 600 5 500 5 600 0 0 0 0 5 R k 0 5 0 6 5 6 5 Pb 0 28 0 0 0 5 Ql 27 6 26 Ql 5 2012 0 0 65 Des Peres 6 0 25 0 0 0 Rock Hill 0 5 6 0 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 0 6 0 6 30 0 30 0 0 Warson Woods 29 0 6 0 6 60 50 5 0 29 0 6 OFM-12-615-GS 5 0 500 0 00 0 6 0 0 5 5 5 5 5 550 Ql 6 0 k 0 Pb Pb 0 5 6 5 5 R 00 R 5Ql 50 0 R 0 5 0 6 0 5 6 5 MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 0 5 0 6 Ql 0 0 R Pb 0 0 0 5 5 0 5 550 6 6 0 Qa 0 DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND LAND SURVEY 0 6 0 0 100 5 0 0 0 5 6 ¬ 0 « 0 550 5 6 0 32 R 6 0 0 0 0 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROGRAM 0 5 5 34 0 6 Ql 0 0 65 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 5 36 32 5 6 0 0 0 100 6 33 6 5 0 «¬ 5 600 6 35 6 0 0 55 Ql 31 50 0 P.O. -

CR08011 Bird Brochure

Your Guide to Birding at CHIMNEY ROCK WELCOME LEGEND TO BIRD LIST Chimney Rock at Chimney Rock State Park, located in Hickory Nut SEASONS Gorge, offers excellent opportuni- Spring - March, April, May ties for bird watching throughout Summer - June, July, August the seasons due to its endless Fall - September, October, November variety of habitats ranging from Winter - December, January, February riverbanks to high cliffs. Along the Rocky Broad River, ABUNDANCE floodplain trees and wet thickets C –Common and widespread, easily seen throughout attract Yellow and Yellow-throated the Park Warblers. Belted Kingfishers may be seen sitting on a branch surveying the river. Climbing up the north-facing slopes, the vegetation changes. Moist cove forests U–Uncommon, smaller numbers present, seen in alternate with drier oak-mixed hardwoods forests. Rhododendrons are very common appropriate habitat in these woods. A mixed oak forest with hickories and dogwoods covers the east side R– Rare, occurs annually in small numbers of the mountain. These deciduous forests attract many summer-breeding birds. A– Accidental, one or two records for the Park Scarlet Tanagers are common, and up to 15 warblers and vireos can be found here * – Breeding confirmed during the summer months. The most elusive of these are the Cerulean and Swainson’s Warblers. Cerulean Warblers prefer the tall trees immediately below the parking lot at the Chimney, and the Swainson’s Warbler is found in rhododendron HABITAT PREFERENCE This outline serves as a guide to the main habitats in the thickets, especially along the Hickory Nut Falls Trail. Park and as a key to the areas where the birds are most The high cliffs on top of the steep, north-facing wooded slopes have an unusually likely to be seen.