Cross-Strait Relations―From the Sole China, Two Chinas and the Greater China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Contemporary Issues Series 57 2-1-1993 Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower? Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower?", Contemporary Issues Series 57, 1993, doi:10.7936/K7DB7ZZ6. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/25. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. Other titles available in this series: 46. The Seeds ofEntrepreneurship, Dwight Lee Greater China: The 47. Capital Mobility: Challenges for Next Economic Superpower? Business and Government, Richard B. McKenzie and Dwight Lee Murray Weidenbaum 48. Business Responsibility in a World of Global Competition, I James B. Burnham 49. Small Wars, Big Defense: Living in a World ofLower Tensions, Murray Weidenbaum 50. "Earth Summit": UN Spectacle with a Cast of Thousands, Murray Weidenbaum Contemporary 51. Fiscal Pollution and the Case Issues Series 57 for Congressional Term Limits, Dwight Lee February 1993 53. Global Warming Research: Learning from NAPAP 's Mistakes, Edward S. Rubin 54. The Case for Taxing Consumption, Murray Weidenbaum 55. Japan's Growing Influence in Asia: Implications for U.S. Business, Steven B. Schlossstein 56. The Mirage of Sustainable Development, Thomas J. DiLorenzo Additional copies are available from: i Center for the Study of American Business Washington University CS1- Campus Box 1208 One Brookings Drive Center for the Study of St. -

Greater China Beef & Sheepmeat Market Snapshot

MARKET SNAPSHOT l BEEF & SHEEPMEAT Despite being the most populous country in the world, the proportion of Chinese consumers who can regularly afford to buy Greater China high quality imported meat is relatively small in comparison to more developed markets such as the US and Japan. However, (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continued strong import demand for premium red meat will be driven by a significant increase in the number of wealthy households. Focusing on targeted opportunities with a differentiated product will help to build preference in what is a large, complex and competitive market. Taiwan and Hong Kong are smaller by comparison but still important markets for Australian red meat, underpinned by a high proportion of affluent households. China meat consumption 1 2 Population Household number by disposable income per capita3 US$35,000+ US$75,000+ 1,444 13% million 94.3 23% 8% 50 kg 56% 44.8 China grocery spend4 10.6 24.2 3.3 5.9 million million 333 26 3.0 51 16.1 Australia A$ Australia Korea China Korea Australia China US US China US Korea 1,573 per person 1,455 million by 2024 5% of total households 0.7% of total households (+1% from 2021) (9% by 2024) (1% by 2024) Australian beef exports to China have grown rapidly, increasing 70-fold over the past 10 years, with the country becoming Australia’s largest market in 2019. Australian beef Australian beef Australia’s share of Australian beef/veal exports – volume5 exports – value6 direct beef imports7 offal cuts exports8 4% 3% 6% 6% 3% Tripe 21% 16% Chilled grass Heart 9% A$ Chilled grain Chilled Australia Tendon Other Frozen grass Frozen 10% 65 71% Tail 17% countries million Frozen grain 84% Kidney 67% Other Total 303,283 tonnes swt Total A$2.83 billion Total 29,687 tonnes swt China has rapidly become Australia’s single largest export destination for both lamb and mutton. -

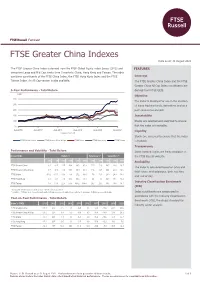

FTSE Greater China Indexes

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China Indexes Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China Index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS) and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks from 3 markets: China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The index combines constituents of the FTSE China Index, the FTSE Hong Kong Index and the FTSE Coverage Taiwan Index. An All Cap version is also available. The FTSE Greater China Index and the FTSE Greater China All Cap Index constituents are 5-Year Performance - Total Return derived from FTSE GEIS. (HKD) Objective 300 The index is designed for use in the creation 250 of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 200 performance benchmark. 150 Investability 100 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 50 that the index is investable. Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Liquidity Data as at month end Stocks are screened to ensure that the index FTSE Greater China FTSE Greater China All Cap FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan is tradable. Transparency Performance and Volatility - Total Return Index methodologies are freely available on Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE Greater China -8.1 -8.7 -1.7 10.4 38.5 81.0 11.5 12.6 18.5 20.6 16.7 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE Greater China All Cap -7.5 -7.6 -0.6 11.5 38.9 80.3 11.6 12.5 18.1 20.4 16.6 total return methodologies, both real time FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 and end of day. -

Scoring One for the Other Team

FIVE TURTLES IN A FLASK: FOR TAIWAN’S OUTER ISLANDS, AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE HOLDS A CERTAIN FATE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Edward W. Green, Jr. Thesis Committee: Eric Harwit, Chairperson Shana J. Brown Cathryn H. Clayton Keywords: Taiwan independence, offshore islands, strait crisis, military intervention TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Scope and Organization ........................................................................................... 6 III. Dramatis Personae: The Five Islands ...................................................................... 9 III.1. Itu Aba ..................................................................................................... 11 III.2. Matsu ........................................................................................................ 14 III.3. The Pescadores ......................................................................................... 16 III.4. Pratas ....................................................................................................... -

FTSE Greater China HKD Index

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China HKD Index Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China HKD Index is an index derived from the FTSE All-World Index and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks providing coverage of 3 markets: China, Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan. For China, the index includes H shares, P Chips and Red Chips listed in Hong Kong Objective and A Shares, B Shares listed in China. Price return, total return and net return versions are The index is designed for use in the creation available for this index. of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 5-Year Performance - Total Return performance benchmark. (HKD) Investability 300 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 250 that the index is investable. 200 Liquidity 150 Stocks are screened to ensure that the index 100 is tradable. 50 Transparency Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Data as at month end Index methodologies are freely available on the FTSE Russell website. FTSE Greater China HKD FTSE Greater China HKD Net of Tax FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan Availability The index is calculated based on price and Performance and Volatility - Total Return total return methodologies, both real time Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** and end of day. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Industry Classification Benchmark FTSE Greater China HKD -7.1 -5.5 1.0 13.1 36.4 80.9 10.9 12.6 19.1 20.1 16.2 (ICB) FTSE Greater China HKD Net of Tax -7.3 -5.7 0.8 12.8 35.1 78.0 10.6 12.2 19.1 20.1 16.2 Index constituents are categorized in FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 accordance with the Industry Classification FTSE Hong Kong -5.0 -0.1 7.0 18.5 19.3 50.3 6.1 8.5 16.8 19.5 17.2 Benchmark (ICB), the global standard for FTSE Taiwan 3.5 10.3 22.5 53.6 103.2 184.4 26.7 23.3 19.5 19.6 18.1 industry sector analysis. -

China Research Trip – UBS Greater China Conference

China Research Trip January 2019 RESEARCH TRIP AGENDA • UBS Greater China Conference and visited nine domestic companies covering: − Logistic and warehousing businesses including e- commerce supply chain fulfillment centres and express delivery parcel sorting facilities − Industrial and advanced robotics manufacturer − Excavator, roller, loader and forklift manufacturers − High precision machinery manufacturers for auto, electronics, white goods, healthcare industries − Plastic moulding machinery manufacturer • Shanghai − Tier 1 city, population of circa 24-25 million • Hangzhou − Tier 2 city, population of circa 6-7 million • Ningbo − Tier 2 city, population of 7-8 million − Busiest port globally (by cargo tonnage) Source: Google Maps 1 KEY THEMES • Key insights • Global outlook • US-China trade tension • Chinese government deleveraging drive • Business, infrastructure and real estate investments • Domestic consumption • Policy response 2 KEY INSIGHTS • Chinese growth is expected to slow structurally (due to demographics, size and economic transition) but economic growth has slowed further over the last 12 months due to government policy on deleveraging and trade uncertainty − Broad-based slowdown in domestic demand, but in particular, slowdown in the auto industry and property market. However, electric vehicle (EV) and online retail sales still growing strongly • Clear evidence of trade uncertainty impacting on demand (both domestic and foreign) from company visits − Decline in new orders over 2018. Some orders cancellation. Logistics -

Invesco Greater China Fund

Mutual Fund Retail Share Classes Invesco Greater China Data as of June 30, 2021 Fund Emerging markets Investment objective An all-cap, long-term investment strategy that offers investors exposure to the Chinese equity market. The fund seeks long-term growth of capital. Performance of a $10,000 investment Portfolio management Class A shares at NAV (June 30, 2011 – June 30, 2021) Mike Shiao • Invesco Greater China Fund - $18,649 Fund facts $20,000 Nasdaq A: AACFX C: CACFX Y: AMCYX R: IGCRX R6: CACSX R5: IACFX Total Net Assets $171,042,766 Total Number of Holdings 35 $10,000 Annual Turnover (as of 10/31/20) 59% Distribution Frequency Annually 0 6/11 6/12 6/13 6/14 6/15 6/16 6/17 6/18 6/19 6/20 6/21 Top 10 holdings (% of total net assets) Alibaba 9.84 Tencent 9.36 Investment results Meituan 'B' 6.16 Average annual total returns (%) as of June 30, 2021 Pinduoduo ADR 4.80 Class A Shares Class C Shares Class Y Shares NetEase ADR 4.80 Inception: Inception: Inception: Style-Specific 03/31/06 03/31/06 10/03/08 Index Asustek Computer 4.48 AIA 4.46 Max Max Load CDSC MSCI China All Gourmet Master 4.22 Period 5.50% NAV 1.00% NAV NAV Shares Index JD.com ADR 4.21 Inception 9.54 9.95 9.51 9.51 10.35 - iQIYI ADR 4.15 10 Years 5.83 6.43 5.79 5.79 6.70 7.42 Holdings are subject to change and are not buy/sell 5 Years 11.75 13.02 12.17 12.17 13.30 14.56 recommendations. -

Involuntary Migrants, Political Revolutionaries and Economic Energisers: a History of the Image of Overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia GORDON C

Journal of Contemporary China (2005), 14(42), February, 55–66 Involuntary Migrants, Political Revolutionaries and Economic Energisers: a history of the image of overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia GORDON C. K. CHEUNG* Along the contemporary migration history of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, three distinctive images have been constructed through the interaction between the overseas Chinese and Mainland China. First, the image of involuntary migrant, formulated by their migration activity and the continuous remittance they sent back to their hometowns, closely linked to the political and social-economic disturbances in the early years of the twentieth century. Second, the image of the overseas Chinese as political revolutionary was heavily politicised by the revolutionary policies of Mainland China in the 1950s and 1960s. Third, through the operational means of foreign direct investment, the overseas Chinese image of economic energiser was re-focused and mirror-imaged with the imperative of the economic reform of Mainland China in the 1970s and 1980s. On the one hand, the images of involuntary migrant, political revolutionary and economic energiser of the Southeast Asian overseas Chinese describe their situational status. On the other hand, these images also reflect the contemporary historical development of Mainland China. Whatever the reasons for studying the Overseas Chinese, there is no doubt that they are a bona fide object of research. The diversity of cultures represented by these people, the diversity of settings in which they have found themselves, the wide differences in the histories of specific Chinese ‘colonies’, all of these things make them a fascinating laboratory for social scientists of various disciplinary bents.1 In Southeast Asia the capitalists were the Chinese. -

The Greater China Area: Retrospect and Prospect

12 The Greater China Area: Retrospect and Prospect The king of the state of Wei intended to attack Handan. Ji Liang heard of this and went to see the king, and said: “Your majesty, on my way here I saw a man driving his carriage which was facing north. He told me that he wanted to go to the state of Chu. ‘Why are you going north?’ I asked. ‘I have fine horses,’ he said. ‘Even though you have good horses, this is not the road to Chu,’ I pointed out. ‘I have plenty of money for my jour- ney,’ he said. ‘But this is not the right direction,’ I said. ‘I have an excellent driver for my carriage,’ he said. The better are the resources, the further he was going from Chu. Now you seek to raise above all the kings and win the support of the common people everywhere. However, you plan to extend your territo- ries and raise your prestige by attacking Handan, relying on the powerful strength of your state and the well-trained soldiers. This is as effective as going north hoping to reach the state of Chu.” – Zhanguoce (475–221 BC) 12.1 Historical evolution The Greater China area is defined in this chapter as one which includes Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau and mainland China.1 In spite of their com- mon history, cultural and linguistic homogeneity, in recent decades the four economic areas have followed divergent political systems, which have resulted in different social and economic performances. As soon as the PRC was founded in 1949, mainland China had effectively adopted and practised a Marxist-Leninist command economy as imposed by the Soviet Union, before it decided to introduce structural reform in the 296 G. -

DSM Greater China Sustainability Report 2018 DSM Greater China Sustainability Report 2018 DSM at a Glance

DSM Greater China Sustainability Report 2018 DSM Greater China Sustainability Report 2018 DSM at a Glance TM DSM – Bright Science. Brighter Living. DSM at a Glance At DSM, we have a long and rich heritage, and it is on that basis that we now enter a new era as a purpose-led company. Our purpose is fully anchored in our purpose-led, performance-driven strategy: creating brighter lives for all. This will serve the interests of all stakeholders – customers, employees, shareholders and society at large – creating value across three dimensions simultaneously: People, Planet and Profit. Nutrition As a company active in Nutrition, Health and Sustainable Living, we address the opportunities that are driven by global megatrends and the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). We contribute to these with our science-based DSM Nutritional Products and DSM Food solutions to create brighter lives for people today and generations to come. Specialties form our Nutrition business. DSM Nutritional Products provides solutions Materials Our bright science has delivered benefits across multiple dimensions, already reaching ~2.5 billion people in the world today in for animal feed, food and beverages, pharmaceuticals, infant nutrition, dietary DSM's Materials business includes DSM our three focus domains of Nutrition & Health, Climate & Energy and Resources & Circularity. supplements, and personal care. DSM Food Engineering Plastics, DSM Dyneema, and DSM Specialties is a leading global supplier Resins & Functional Materials. DSM is a global We are a company that is striving to do well by doing good – because ultimately, we cannot be successful, nor even call of specialty food enzymes, cultures, bio- player in specialty plastics for the electrical ourselves successful, in a world that fails. -

2021 Greater China ETF Investor Survey Introduction

EXCHANGE THOUGHTS 2021 Greater China ETF Investor Survey Introduction As part of our eighth annual ETF Survey, we broke out Greater China respondents Content: to outline the emerging trends in usage, • Greater China ETF Marketplace..............................................2 selection, and demand for exchange-traded • Thematic ETFs............................................................................5 funds in the region. • China Cross-Border....................................................................7 Brown Brothers Harriman (BBH) recently surveyed more than 300 institutional investors, financial advisers, and fund managers from around the • ESG ETFs...................................................................................10 world (U.S., Europe, and Greater China – including Mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan). This fourth annual supplemental report takes a closer look at the • Active and Fixed Income ETFs...............................................13 Greater China responses. In Greater China, the sample was 58% institutional investors, 20% financial advisers, and 22% fund managers. All respondents invest in ETFs and are aware of their institution’s overall investment strategy. 2021 Greater China ETF Investor Survey | 1 Greater China ETF Marketplace Key Findings: 146 respondents in • The pace of ETF adoption in Mainland China is ramping up. An astonishing 92% Greater China, representing of Mainland investors expect to increase their ETF allocation in the next 12 months, an Mainland, Hong Kong, and Taiwan increase of 10 percentage points from 2020. • Thematic ETFs get the green light. There’s resounding interest across the region with 91% of Mainland investors, 86% of Hong Kong investors, and 74% of Taiwan investors looking to increase allocations to thematic ETFs this year. 76% manage more than • Mainland access continues to draw interest from global investors. 86% of global $100 million (USD) in assets investors plan to increase investment into the Mainland equity and bond markets in 2021. -

Economic Interdependence and the Development of Cross-‐Strait

Lu 1 Economic Interdependence and the Development of Cross-Strait Relations To what degree can economic interdependence encourage peace in the inherently conflictual relationship between China and Taiwan? Undergraduate Honors Thesis, Sanford School of Public Policy Duke University, Durham, NC Michelle Lu December 2011 Professor Jentleson Professor Kelley 2 Lu Abstract By measuring the extent to which improved economic relations between China and Taiwan has led to improved political relations, this proJect uses the case of cross-Strait relations to test the idea that economic interdependence encourages peace. Trade ties and indicators of political relations measure the extent to which economic interdependence can encourage peace and work toward conflict resolution in an inherently conflictual relationship. Economic interdependence expands contacts between states, encourages the building of cooperative institutions, and introduces new incentives for peace over conflict. This paper argues that economic interdependence is not sufficient to resolve political conflict, but it builds an environment conducive to improved political relations and easing of tensions. These improvements are not high-level, political, diplomatic ties but rather the building of lower level political and societal exchange. Trade relations have grown between China and Taiwan from 2003 and 2011, and this economic interdependence is correlated with expanded interaction in tourism, transportation, political dialogue and cultural exchange. These effects allow for greater mutual understanding and contact, which create a reciprocal effect by contributing to increased economic interaction. While progress in cross-Strait relations is constrained by the internal politics of both China and Taiwan at any moment, the United States plays an important role in reinforcing the positive effects of economic interdependence.