Economic Interdependence and the Development of Cross-‐Strait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Contemporary Issues Series 57 2-1-1993 Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower? Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower?", Contemporary Issues Series 57, 1993, doi:10.7936/K7DB7ZZ6. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/25. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. Other titles available in this series: 46. The Seeds ofEntrepreneurship, Dwight Lee Greater China: The 47. Capital Mobility: Challenges for Next Economic Superpower? Business and Government, Richard B. McKenzie and Dwight Lee Murray Weidenbaum 48. Business Responsibility in a World of Global Competition, I James B. Burnham 49. Small Wars, Big Defense: Living in a World ofLower Tensions, Murray Weidenbaum 50. "Earth Summit": UN Spectacle with a Cast of Thousands, Murray Weidenbaum Contemporary 51. Fiscal Pollution and the Case Issues Series 57 for Congressional Term Limits, Dwight Lee February 1993 53. Global Warming Research: Learning from NAPAP 's Mistakes, Edward S. Rubin 54. The Case for Taxing Consumption, Murray Weidenbaum 55. Japan's Growing Influence in Asia: Implications for U.S. Business, Steven B. Schlossstein 56. The Mirage of Sustainable Development, Thomas J. DiLorenzo Additional copies are available from: i Center for the Study of American Business Washington University CS1- Campus Box 1208 One Brookings Drive Center for the Study of St. -

Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018)

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-18-2018 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross- Strait Relations Jing Feng [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Recommended Citation Feng, Jing, "Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 777. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/777 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China’s Cross-Strait Relationship Jing Feng Capstone Project APS 650 Professor Brian Komei Dempster May 15, 2018 2 Abstract Taiwan’s strategic geopolitical position—along with domestic political developments—have put the country in turmoil ever since the post-Chinese civil war. In particular, its antagonistic, cross-strait relationship with China has led to various negative consequences and cast a spotlight on the country on the international diplomatic front for close to over six decades. After the end of the Cold War, the democratization of Taiwan altered her political identity and released a nation-building process that was seemingly irreversible. Taiwan’s nation-building efforts have moved the nation further away from reunification with China. -

Who Set the Narrative? Assessing the Influence of Chinese Media in News Coverage of COVID-19 in 30 African Countries the Size Of

Who Set the Narrative? Assessing the Influence of Chinese Media in News Coverage of COVID-19 in 30 African Countries The size of China’s State-owned media’s operations in Africa has grown significantly since the early 2000s. Previous research on the impact of increased Sino-African mediated engagements has been inconclusive. Some researchers hold that public opinion towards China in African nations has been improving because of the increased media presence. Others argue that the impact is rather limited, particularly when it comes to affecting how African media cover China- related stories. This paper seeks to contribute to this debate by exploring the extent to which news media in 30 African countries relied on Chinese news sources to cover China and the COVID-19 outbreak during the first half of 2020. By computationally analyzing a corpus of 500,000 news stories, I show that, compared to other major global players (e.g. Reuters, AFP), content distributed by Chinese media (e.g. Xinhua, China Daily, People’s Daily) is much less likely to be used by African news organizations, both in English and French speaking countries. The analysis also reveals a gap in the prevailing themes in Chinese and African media’s coverage of the pandemic. The implications of these findings for the sub-field of Sino-African media relations, and the study of global news flows is discussed. Keywords: China-Africa, Xinhua, news agencies, computational text analysis, big data, intermedia agenda setting Beginning in the mid-2010s, Chinese media began to substantially increase their presence in many African countries, as part of China’s ambitious going out strategy that covered a myriad of economic activities, including entertainment, telecommunications and news content (Keane, 2016). -

Cross-Strait Economic Ties: RAMON H

ASIA PROGRAM SPECIAL REPORT NO. 118 FEBRUARY 2004 INSIDE Cross-Strait Economic Ties: RAMON H. MYERS Taiwan-China Agent of Change, or a Trojan Horse? Economic Relations: Promoting Mutual Benefits or ABSTRACT: This Special Report discusses both opportunities and challenges of cross–Taiwan Undermining Taiwan’s Strait economic ties for domestic economic developments in China and Taiwan as well as their Security? bilateral relationship. Ramon H. Myers of the Hoover Institution argues that Taiwan will gain page 4 economically,build friendship and trust, and pave the way for a long-term solution of the divid- ed-China issue by engaging China. Terry Cooke of the Foreign Policy Research Institute main- TERRY COOKE tains that economic globalization will bring about regional stability and reduce military and Cross-Strait Economic political tension across the Taiwan Strait.Tun-jen Cheng of the College of William and Mary Ties & the Dynamics of suggests that the principal hazard for Taiwan because of the concentration of Taiwan’s trade with Globalization and investment in China is recession or currency fluctuation on the mainland.While the three essays agree that Beijing is unlikely to use Taiwan’s economic dependence on the mainland to page 8 coerce Taiwan politically,they differ on whether the growing cross-Strait economic ties will nec- TUN-JEN CHENG essarily bring about economic benefits to Taiwan. Doing Business with China: Taiwan’s Three Main Concerns Introduction mainland has accumulated to about $30 bil- Gang Lin lion. Investment on the mainland has expand- page 12 ed from labor-intensive industries to capital- espite pervasive political distrust and intensive and technology-intensive ventures. -

Greater China Beef & Sheepmeat Market Snapshot

MARKET SNAPSHOT l BEEF & SHEEPMEAT Despite being the most populous country in the world, the proportion of Chinese consumers who can regularly afford to buy Greater China high quality imported meat is relatively small in comparison to more developed markets such as the US and Japan. However, (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continued strong import demand for premium red meat will be driven by a significant increase in the number of wealthy households. Focusing on targeted opportunities with a differentiated product will help to build preference in what is a large, complex and competitive market. Taiwan and Hong Kong are smaller by comparison but still important markets for Australian red meat, underpinned by a high proportion of affluent households. China meat consumption 1 2 Population Household number by disposable income per capita3 US$35,000+ US$75,000+ 1,444 13% million 94.3 23% 8% 50 kg 56% 44.8 China grocery spend4 10.6 24.2 3.3 5.9 million million 333 26 3.0 51 16.1 Australia A$ Australia Korea China Korea Australia China US US China US Korea 1,573 per person 1,455 million by 2024 5% of total households 0.7% of total households (+1% from 2021) (9% by 2024) (1% by 2024) Australian beef exports to China have grown rapidly, increasing 70-fold over the past 10 years, with the country becoming Australia’s largest market in 2019. Australian beef Australian beef Australia’s share of Australian beef/veal exports – volume5 exports – value6 direct beef imports7 offal cuts exports8 4% 3% 6% 6% 3% Tripe 21% 16% Chilled grass Heart 9% A$ Chilled grain Chilled Australia Tendon Other Frozen grass Frozen 10% 65 71% Tail 17% countries million Frozen grain 84% Kidney 67% Other Total 303,283 tonnes swt Total A$2.83 billion Total 29,687 tonnes swt China has rapidly become Australia’s single largest export destination for both lamb and mutton. -

Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO Qingjiang Kong

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Journal of International Law 2005 Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO Qingjiang Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kong, Qingjiang, "Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO" (2005). Minnesota Journal of International Law. 220. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Journal of International Law collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO? Qingjiang Kong* INTRODUCTION On December 11, 2001, China acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO).1 Taiwan followed on January 1, 2002 as the "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu."2 Accession of both China and Taiwan to the world trading body has triggered a fever of activities by Taiwanese businesses, but the governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait have been slow to make policy adjustments. The coexis- tence of business enthusiasm and governmental indifference * Professor of International Economic Law, Zhejiang Gongshang University (previ- ously: Hangzhou University of Commerce), China. His recent book is China and the World Trade Organization:A Legal Perspective (New Jersey, London, Singapore, Hong Kong, World Scientific Publishing, 2002). Questions or comments may be e- mailed to Professor Kong at [email protected]. -

China As a Hybrid Influencer: Non-State Actors As State Proxies COI HYBRID INFLUENCE COI

Hybrid CoE Research Report 1 JUNE 2021 China as a hybrid influencer: Non-state actors as state proxies COI HYBRID INFLUENCE COI JUKKA AUKIA Hybrid CoE Hybrid CoE Research Report 1 China as a hybrid influencer: Non-state actors as state proxies JUKKA AUKIA 3 Hybrid CoE Research Reports are thorough, in-depth studies providing a deep understanding of hybrid threats and phenomena relating to them. Research Reports build on an original idea and follow academic research report standards, presenting new research findings. They provide either policy-relevant recommendations or practical conclusions. COI Hybrid Influence looks at how state and non-state actors conduct influence activities targeted at Participating States and institutions, as part of a hybrid campaign, and how hostile state actors use their influence tools in ways that attempt to sow instability, or curtail the sovereignty of other nations and the independence of institutions. The focus is on the behaviours, activities, and tools that a hostile actor can use. The goal is to equip practitioners with the tools they need to respond to and deter hybrid threats. COI HI is led by the UK. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats tel. +358 400 253 800 www.hybridcoe.fi ISBN (web) 978-952-7282-78-6 ISBN (print) 978-952-7282-79-3 ISSN 2737-0860 June 2021 Hybrid CoE is an international hub for practitioners and experts, building Participating States’ and institutions’ capabilities and enhancing EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats, located in Helsinki, Finland. The responsibility for the views expressed ultimately rests with the authors. -

Retweeting Through the Great Firewall a Persistent and Undeterred Threat Actor

Retweeting through the great firewall A persistent and undeterred threat actor Dr Jake Wallis, Tom Uren, Elise Thomas, Albert Zhang, Dr Samantha Hoffman, Lin Li, Alex Pascoe and Danielle Cave Policy Brief Report No. 33/2020 About the authors Dr Jacob Wallis is a Senior Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Tom Uren is a Senior Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Elise Thomas is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Albert Zhang is a Research Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Dr Samanthan Hoffman is an Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Lin Li is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Alex Pascoe is a Research Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Danielle Cave is Deputy Director of the International Cyber Policy Centre. Acknowledgements ASPI would like to thank Twitter for advanced access to the takedown dataset that formed a significant component of this investigation. The authors would also like to thank ASPI colleagues who worked on this report. What is ASPI? The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally. ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) is a leading voice in global debates on cyber and emerging technologies and their impact on broader strategic policy. -

Xi Jinping's Address to the Central Conference On

Xi Jinping’s Address to the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs: Assessing and Advancing Major- Power Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics Michael D. Swaine* Xi Jinping’s speech before the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs—held November 28–29, 2014, in Beijing—marks the most comprehensive expression yet of the current Chinese leadership’s more activist and security-oriented approach to PRC diplomacy. Through this speech and others, Xi has taken many long-standing Chinese assessments of the international and regional order, as well as the increased influence on and exposure of China to that order, and redefined and expanded the function of Chinese diplomacy. Xi, along with many authoritative and non-authoritative Chinese observers, presents diplomacy as an instrument for the effective application of Chinese power in support of an ambitious, long-term, and more strategic foreign policy agenda. Ultimately, this suggests that Beijing will increasingly attempt to alter some of the foreign policy processes and power relationships that have defined the political, military, and economic environment in the Asia- Pacific region. How the United States chooses to respond to this challenge will determine the Asian strategic landscape for decades to come. On November 28 and 29, 2014, the Central Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership convened its fourth Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs (中央外事工作会)—the first since August 2006.1 The meeting, presided over by Premier Li Keqiang, included the entire Politburo Standing Committee, an unprecedented number of central and local Chinese civilian and military officials, nearly every Chinese ambassador and consul-general with ambassadorial rank posted overseas, and commissioners of the Foreign Ministry to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Macao Special Administrative Region. -

The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan Independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Dalei Jie University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Jie, Dalei, "The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 524. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Abstract How to explain the rise and fall of the Taiwan independence policy? As the Taiwan Strait is still the only conceivable scenario where a major power war can break out and Taiwan's words and deeds can significantly affect the prospect of a cross-strait military conflict, ot answer this question is not just a scholarly inquiry. I define the aiwanT independence policy as internal political moves by the Taiwanese government to establish Taiwan as a separate and sovereign political entity on the world stage. Although two existing prevailing explanations--electoral politics and shifting identity--have some merits, they are inadequate to explain policy change over the past twenty years. Instead, I argue that there is strategic rationale for Taiwan to assert a separate sovereignty. Sovereignty assertions are attempts to substitute normative power--the international consensus on the sanctity of sovereignty--for a shortfall in military- economic-diplomatic assets. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 6, 2016 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–471 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Cochairman Chairman JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TOM COTTON, Arkansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois BEN SASSE, Nebraska DIANE BLACK, Tennessee DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio GARY PETERS, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California TED LIEU, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS CHRISTOPHER P. LU, Department of Labor SARAH SEWALL, Department of State DANIEL R. RUSSEL, Department of State TOM MALINOWSKI, Department of State PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Overview ............................................................................................................ 5 Recommendations to Congress and the Administration .............................. -

FTSE Greater China Indexes

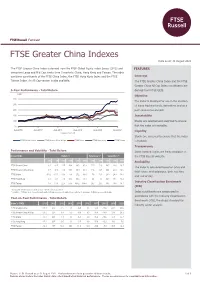

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China Indexes Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China Index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS) and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks from 3 markets: China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The index combines constituents of the FTSE China Index, the FTSE Hong Kong Index and the FTSE Coverage Taiwan Index. An All Cap version is also available. The FTSE Greater China Index and the FTSE Greater China All Cap Index constituents are 5-Year Performance - Total Return derived from FTSE GEIS. (HKD) Objective 300 The index is designed for use in the creation 250 of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 200 performance benchmark. 150 Investability 100 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 50 that the index is investable. Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Liquidity Data as at month end Stocks are screened to ensure that the index FTSE Greater China FTSE Greater China All Cap FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan is tradable. Transparency Performance and Volatility - Total Return Index methodologies are freely available on Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE Greater China -8.1 -8.7 -1.7 10.4 38.5 81.0 11.5 12.6 18.5 20.6 16.7 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE Greater China All Cap -7.5 -7.6 -0.6 11.5 38.9 80.3 11.6 12.5 18.1 20.4 16.6 total return methodologies, both real time FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 and end of day.