Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of China and the Brics Project

Esta revista forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx exican M L Review aw New Series V O L U M E VII Number 1 THE ROLE OF CHINA AND THE BRICS PROJECT Arturo OROPEZA GARCÍA* ABSTRACT. BRICS is an exogenous invention that was institutionalized as a convenient geopolitical market strategy, which favored each of the five BRICS countries to a greater or a lesser degree. As such, it is now a political group without deep roots and its future will be conditioned by any dividends it might yield over the coming years as a result of political, economic and social correla- tions and divergences. KEY WORDS: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. RESUMEN. El grupo de los BRICS es una invención exógena que se institu- cionalizó bajo la conveniencia de una estrategia geopolítica de mercado, que en mayor o menor grado ha favorecido a cada uno de los cinco países que lo conforman. De esta manera, hoy en día es un grupo político que carece de raíces profundas y cuyo futuro estará condicionado por los dividendos que pueda pro- ducir en los próximos años como resultado de sus correlaciones y divergencias políticas, económicas y sociales. PALABRAS CLAVE: Brasil, Rusia, India, China y Sudáfrica. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................... 110 II. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 110 III. THE IMPORTANT ROLE OF CHINA WITHIN THE BRICS GROUP ........... 113 IV. GOODBYE NEO-LIBERALISM? WELCOME MARKET SOCIALISM? ............ 116 V. T HE WORLD ACCORDING TO GOLDMAN SACHS? ............................... -

Greater China Beef & Sheepmeat Market Snapshot

MARKET SNAPSHOT l BEEF & SHEEPMEAT Despite being the most populous country in the world, the proportion of Chinese consumers who can regularly afford to buy Greater China high quality imported meat is relatively small in comparison to more developed markets such as the US and Japan. However, (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continued strong import demand for premium red meat will be driven by a significant increase in the number of wealthy households. Focusing on targeted opportunities with a differentiated product will help to build preference in what is a large, complex and competitive market. Taiwan and Hong Kong are smaller by comparison but still important markets for Australian red meat, underpinned by a high proportion of affluent households. China meat consumption 1 2 Population Household number by disposable income per capita3 US$35,000+ US$75,000+ 1,444 13% million 94.3 23% 8% 50 kg 56% 44.8 China grocery spend4 10.6 24.2 3.3 5.9 million million 333 26 3.0 51 16.1 Australia A$ Australia Korea China Korea Australia China US US China US Korea 1,573 per person 1,455 million by 2024 5% of total households 0.7% of total households (+1% from 2021) (9% by 2024) (1% by 2024) Australian beef exports to China have grown rapidly, increasing 70-fold over the past 10 years, with the country becoming Australia’s largest market in 2019. Australian beef Australian beef Australia’s share of Australian beef/veal exports – volume5 exports – value6 direct beef imports7 offal cuts exports8 4% 3% 6% 6% 3% Tripe 21% 16% Chilled grass Heart 9% A$ Chilled grain Chilled Australia Tendon Other Frozen grass Frozen 10% 65 71% Tail 17% countries million Frozen grain 84% Kidney 67% Other Total 303,283 tonnes swt Total A$2.83 billion Total 29,687 tonnes swt China has rapidly become Australia’s single largest export destination for both lamb and mutton. -

THE ROLE of CHINA and the BRICS PROJECT Arturo OROPEZA

Esta revista forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx http://biblio.juridicas.unam.mx exican M Review aw New Series L V O L U M E VII Number 1 THE ROLE OF CHINA AND THE BRICS PROJECT Arturo OROPEZA GARCÍA* ABSTRACT. BRICS is an exogenous invention that was institutionalized as a convenient geopolitical market strategy, which favored each of the five BRICS countries to a greater or a lesser degree. As such, it is now a political group without deep roots and its future will be conditioned by any dividends it might yield over the coming years as a result of political, economic and social correla- tions and divergences. KEY WORDS: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. RESUMEN. El grupo de los BRICS es una invención exógena que se institu- cionalizó bajo la conveniencia de una estrategia geopolítica de mercado, que en mayor o menor grado ha favorecido a cada uno de los cinco países que lo conforman. De esta manera, hoy en día es un grupo político que carece de raíces profundas y cuyo futuro estará condicionado por los dividendos que pueda pro- ducir en los próximos años como resultado de sus correlaciones y divergencias políticas, económicas y sociales. PALABRAS CLAVE: Brasil, Rusia, India, China y Sudáfrica. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................... 110 II. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 110 III. THE IMPORTANT ROLE OF CHINA WITHIN THE BRICS GROUP ........... 113 IV. GOODBYE NEO-LIBERALISM? WELCOME MARKET SOCIALISM? ............ 116 V. THE WORLD ACCORDING TO GOLDMAN SACHS? ................................ 130 * Doctor of Law and Researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [Institute for Legal Research at the National Autonomous University of Mexico]. -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Sino-US Rivalry: Non-Negotiables for US Approaches to Southeast Asia

ISSUE: 2020 No. 122 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 22 October 2020 Sino-US Rivalry: Non-Negotiables for US Approaches to Southeast Asia William Choong* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Since 2016, China has presented itself as a strategic competitor to the United States in terms of its government, political ideology and economic system. • The Trump administration has been accused of incoherence in its policies toward China. However, it can be argued that it introduced the concept of reciprocity into the bilateral relationship and acted in strength to challenge China in the South China Sea. • The Trump’s administration approach to the Indo-Pacific has led to concerns in regional states. The transactional approach towards allies, divergences between Trump and his senior officials in statements about alliances and America’s regional presence, as well as the implementation of US policy toward China have sowed confusion. • Whether it be a Trump or Biden victory come November, Washington needs to recognise some non-negotiables with regard to Southeast Asia: o the avoidance of making regional states make binary choices in the Sino-US rivalry; o the need for a looser cooperative approach in pushing back China’s assertiveness; o and the need to build regional connectivity networks and infrastructure. *William Choong is Senior Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. 1 ISSUE: 2020 No. 122 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION Writing 14 months into the Trump administration in March 2018, Kurt Campbell and Ely Ratner – two senior officials who had served in the Obama Administration – argued that Washington had always had an “outsized sense” of its ability to determine China’s trajectory. -

Rising Tiger and Leaping Dragon: Emerging Global Dynamics and Space for Developing Countries and Least Developed Countries

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IDS OpenDocs Rising Tiger and Leaping Dragon: Emerging Global Dynamics and Space for Developing Countries and Least Developed Countries S.K. Mohanty and Sachin Chaturvedi 1 Introduction Section 2 presents broad macroeconomic facts about The growth in resilient economy of Asia led by China and India, while Section 3 presents their China and increasingly shared by India is a process trade relations and complementarities with other attracting huge international attention. Chinese developing countries. Innovation and technology- exports of mass production items have caused related issues are discussed in Section 4. The serious concern; and some studies have predicted conclusions are drawn in the last section. that this might contribute to recession in the US (Palley 2004). In contrast to this negative 2 Emergence of Sino–Indian perspective, the focus in the Asian region has been economy: basic parameters on the opportunities for economic and financial China’s growth surge started in the late 1970s and integration and the possible strategies to tap them India’s in the early 1990s. The combined size of (Kumar 2004). The expansion of these two the Indian and Chinese economies in the early economies may be compared with the growth of 1990s was US$681bn in constant international economies in the European Union. It may be noted dollar terms in 1990 (World Bank 2005). The that integration of the European Union has collective size of their economies was larger than immensely benefited Member countries, and some the combined size of some of the smaller economies of the slow-growing economies have gained strength of Europe, such as Iceland, Luxemburg, Portugal, from the regional arrangement. -

U.S.-Japan-China Relations Trilateral Cooperation in the 21St Century

U.S.-Japan-China Relations Trilateral Cooperation in the 21st Century Conference Report By Brad Glosserman Issues & Insights Vol. 5 – No. 10 Honolulu, Hawaii September 2005 Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, the Pacific Forum CSIS (www.csis.org/pacfor/) operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, DC. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic, business, and oceans policy issues through analysis and dialogue undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate areas. Founded in 1975, it collaborates with a broad network of research institutes from around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating project findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and members of the public throughout the region. Table of Contents Page Acknowledgements iv Executive Summary v Report The year in review 1 Energy security and the impact on trilateral cooperation 4 Issues in the bilateral relationship 6 Opportunities for cooperation 9 Selected Papers United States, Japan, and China Relations: Trilateral Cooperation in the 21st Century by Yoshihide Soeya 15 Chinese Perspectives on Global and Regional Security Issues by Gao Zugui 23 Sino-U.S. Relations: Healthy Competition or Strategic Rivalry? by Bonnie S. Glaser 27 Sino-U.S. Relations: Four Immediate Challenges by Niu Xinchun 35 Sino-Japanese Relations 60 Years after the War: a Japanese View by Akio Takahara 39 Building Sino-Japanese Relations Oriented toward the 21st Century by Ma Junwei 47 Comments on Sino-Japanese Relations by Ezra F. Vogel 51 The U.S.-Japan Relationship: a Japanese View by Koji Murata 55 Toward Closer Sino-U.S.-Japan Relations: Steps Needed by Liu Bo 59 The China-Japan-U.S. -

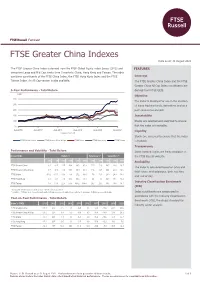

FTSE Greater China Indexes

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China Indexes Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China Index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS) and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks from 3 markets: China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The index combines constituents of the FTSE China Index, the FTSE Hong Kong Index and the FTSE Coverage Taiwan Index. An All Cap version is also available. The FTSE Greater China Index and the FTSE Greater China All Cap Index constituents are 5-Year Performance - Total Return derived from FTSE GEIS. (HKD) Objective 300 The index is designed for use in the creation 250 of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 200 performance benchmark. 150 Investability 100 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 50 that the index is investable. Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Liquidity Data as at month end Stocks are screened to ensure that the index FTSE Greater China FTSE Greater China All Cap FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan is tradable. Transparency Performance and Volatility - Total Return Index methodologies are freely available on Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE Greater China -8.1 -8.7 -1.7 10.4 38.5 81.0 11.5 12.6 18.5 20.6 16.7 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE Greater China All Cap -7.5 -7.6 -0.6 11.5 38.9 80.3 11.6 12.5 18.1 20.4 16.6 total return methodologies, both real time FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 and end of day. -

Asia Observatory

ASIA OBSERVATORY BAO-37/2019(41) September 09 - 15, 2019 Bosphorus Center for Asian Studies Ankara 2019 2019 © All Rights Reserved. No part of this piece may be reproduced, copied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or printed, without the permission of BAAM. The views expressed in this piece are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect our stance or policy. 2019 © Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. BAAM’ın izni alınmadan kısmen veya tamamen elektronik veya basılı olarak çoğaltılamaz, dağıtılamaz ve yayınlanamaz. Yazıda belirtilen görüşler yazara aittir ve BAAM’ın görüşlerini yansıtmak zorunda değildir. Internet: www.bogaziciasya.com E-Mail: [email protected] Twitter: @bogaziciasya_en - @bogaziciasya 2 Bosphorus Center for Asian Studies Bosphorus Center for Asian Studies (BAAM), founded in April 2018 in Ankara, is an independent think tank operating as an initiative of the Bosphorus Association for Social Research (BOSAR). In addition to Ankara and Istanbul, there are a total of 20 researchers who make contributions from different countries. BAAM is conducting research on the Asian region, mainly the Far East. Major areas of our studies include Asian Politics, Belt and Road Initiative, Great Power Competition, Foreign Policy of China, Political Economy of Asia Pacific Region, and the Turkey- Asia relations. The reports, briefings, opinions, translations and special news prepared by BAAM researchers are published on bogaziciasya.com and the weekly Asian Observatory bulletin which is shared with related individuals and organizations via Internet. Among the languages that the researchers in the team are able to read and write are French, Italian, Japanese and Amharic as well as English and Chinese. -

Scoring One for the Other Team

FIVE TURTLES IN A FLASK: FOR TAIWAN’S OUTER ISLANDS, AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE HOLDS A CERTAIN FATE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Edward W. Green, Jr. Thesis Committee: Eric Harwit, Chairperson Shana J. Brown Cathryn H. Clayton Keywords: Taiwan independence, offshore islands, strait crisis, military intervention TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Scope and Organization ........................................................................................... 6 III. Dramatis Personae: The Five Islands ...................................................................... 9 III.1. Itu Aba ..................................................................................................... 11 III.2. Matsu ........................................................................................................ 14 III.3. The Pescadores ......................................................................................... 16 III.4. Pratas ....................................................................................................... -

FTSE Greater China HKD Index

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China HKD Index Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China HKD Index is an index derived from the FTSE All-World Index and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks providing coverage of 3 markets: China, Hong Kong SAR and Taiwan. For China, the index includes H shares, P Chips and Red Chips listed in Hong Kong Objective and A Shares, B Shares listed in China. Price return, total return and net return versions are The index is designed for use in the creation available for this index. of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 5-Year Performance - Total Return performance benchmark. (HKD) Investability 300 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 250 that the index is investable. 200 Liquidity 150 Stocks are screened to ensure that the index 100 is tradable. 50 Transparency Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Data as at month end Index methodologies are freely available on the FTSE Russell website. FTSE Greater China HKD FTSE Greater China HKD Net of Tax FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan Availability The index is calculated based on price and Performance and Volatility - Total Return total return methodologies, both real time Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** and end of day. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Industry Classification Benchmark FTSE Greater China HKD -7.1 -5.5 1.0 13.1 36.4 80.9 10.9 12.6 19.1 20.1 16.2 (ICB) FTSE Greater China HKD Net of Tax -7.3 -5.7 0.8 12.8 35.1 78.0 10.6 12.2 19.1 20.1 16.2 Index constituents are categorized in FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 accordance with the Industry Classification FTSE Hong Kong -5.0 -0.1 7.0 18.5 19.3 50.3 6.1 8.5 16.8 19.5 17.2 Benchmark (ICB), the global standard for FTSE Taiwan 3.5 10.3 22.5 53.6 103.2 184.4 26.7 23.3 19.5 19.6 18.1 industry sector analysis. -

Unions Help Increase Wealth for All and Close Racial Wealth Gaps by Aurelia Glass, David Madland, and Christian E

Unions Help Increase Wealth for All and Close Racial Wealth Gaps By Aurelia Glass, David Madland, and Christian E. Weller September 6, 2021 The United States faces large wealth divides, particularly by race and ethnicity. The median white family has about 10 times the wealth of the median Black family and more than eight times the wealth of the median Hispanic family.1 Wealth is also much more unequally distributed than income, with the top 5 percent of families hold- ing about 250 times as much wealth as the median family.2 Unions play a key role in redressing these large wealth gaps. They increase wealth for all households—no matter their race or ethnicity—and tend to provide larger increases for Black and Hispanic households than for white households. Unions help households by raising incomes, increasing benefits, and improving the quality and stability of jobs.3 All these things lead to both direct and indirect increases in wealth. When workers earn more money through union contracts, for example, they are able to set aside more of their paychecks and enjoy the additional tax incentives that come with saving.4 Moreover, benefits such as pension plans grow wealth, while others such as health or life insurance reduce the amount union members need to spend from their own savings during periods of illness or income loss. This helps cushion families’ savings against downturns like the recent COVID- 19-induced recession, and additional savings can be put toward a child’s college education or the purchase of a home.5 Finally, strong union