Response to the Anti-Japanese Campaign in China on Hong Kong’S Internet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Contemporary Issues Series 57 2-1-1993 Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower? Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower?", Contemporary Issues Series 57, 1993, doi:10.7936/K7DB7ZZ6. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/25. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. Other titles available in this series: 46. The Seeds ofEntrepreneurship, Dwight Lee Greater China: The 47. Capital Mobility: Challenges for Next Economic Superpower? Business and Government, Richard B. McKenzie and Dwight Lee Murray Weidenbaum 48. Business Responsibility in a World of Global Competition, I James B. Burnham 49. Small Wars, Big Defense: Living in a World ofLower Tensions, Murray Weidenbaum 50. "Earth Summit": UN Spectacle with a Cast of Thousands, Murray Weidenbaum Contemporary 51. Fiscal Pollution and the Case Issues Series 57 for Congressional Term Limits, Dwight Lee February 1993 53. Global Warming Research: Learning from NAPAP 's Mistakes, Edward S. Rubin 54. The Case for Taxing Consumption, Murray Weidenbaum 55. Japan's Growing Influence in Asia: Implications for U.S. Business, Steven B. Schlossstein 56. The Mirage of Sustainable Development, Thomas J. DiLorenzo Additional copies are available from: i Center for the Study of American Business Washington University CS1- Campus Box 1208 One Brookings Drive Center for the Study of St. -

Resisting Chinese Linguistic Imperialism

UYGHUR HUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT SPECIAL REPORT Resisting Chinese Linguistic Imperialism: Abduweli Ayup and the Movement for Uyghur Mother Tongue-Based Education Rustem Shir, Research Associate Logo of the Ana Til Balilar Baghchisi (Mother Tongue Children’s Garden) May 2019 Contents Acknowledgement 4 Introduction 5 1. CCP language policy on education in East Turkestan 6 Foundations of CCP ethnic minority policy 6 Eras of minority language tolerance 9 Primary and secondary school ‘bilingual’ education policy 12 The Xinjiang Class 20 Mandarin as the language of instruction at Xinjiang University 22 Preschool and kindergarten ‘bilingual’ education policy 23 Suppression of the Movement for Uyghur Mother Tongue-Based Education 26 The Hotan Prefecture and Ghulja County Department of Education directives 28 Internment camps 29 Discussion 32 2. ABduweli Ayup and the Movement for Uyghur Mother Tongue-Based Education 36 Upal: Why couldn’t we study Kashgari? 36 Toquzaq: Oyghan! (Wake Up!) 38 Beijing: Our campus felt like a minority region 41 Doletbagh: My sad history repeating in front of me 50 Urumchi: Education for assimilation 55 Lanzhou: Are you bin Laden? 60 Ankara: Ethno-nationalism and a counterbalance 67 Urumchi: For the love of community 72 Lawrence: Disconnected 77 Kashgar: Rise of the Movement for Uyghur Mother Tongue-Based Education 81 Urumchi: Just keep silent 89 Kashgar: You’re going to be arrested 93 Doletbagh Detention Center: No choice, brother 98 Urumchi Tengritagh Detention Center: Qorqma (Don’t be afraid) 104 Urumchi Liudaowan Prison: Every color had disappeared 109 Urumchi Koktagh Prison: Do you want to defend yourself? 124 2 Urumchi/Kashgar: Release and return 127 Kashgar: Open-air prison 131 Ankara: Stateless and stranded 138 Paris: A new beginning 146 3. -

Greater China Beef & Sheepmeat Market Snapshot

MARKET SNAPSHOT l BEEF & SHEEPMEAT Despite being the most populous country in the world, the proportion of Chinese consumers who can regularly afford to buy Greater China high quality imported meat is relatively small in comparison to more developed markets such as the US and Japan. However, (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continued strong import demand for premium red meat will be driven by a significant increase in the number of wealthy households. Focusing on targeted opportunities with a differentiated product will help to build preference in what is a large, complex and competitive market. Taiwan and Hong Kong are smaller by comparison but still important markets for Australian red meat, underpinned by a high proportion of affluent households. China meat consumption 1 2 Population Household number by disposable income per capita3 US$35,000+ US$75,000+ 1,444 13% million 94.3 23% 8% 50 kg 56% 44.8 China grocery spend4 10.6 24.2 3.3 5.9 million million 333 26 3.0 51 16.1 Australia A$ Australia Korea China Korea Australia China US US China US Korea 1,573 per person 1,455 million by 2024 5% of total households 0.7% of total households (+1% from 2021) (9% by 2024) (1% by 2024) Australian beef exports to China have grown rapidly, increasing 70-fold over the past 10 years, with the country becoming Australia’s largest market in 2019. Australian beef Australian beef Australia’s share of Australian beef/veal exports – volume5 exports – value6 direct beef imports7 offal cuts exports8 4% 3% 6% 6% 3% Tripe 21% 16% Chilled grass Heart 9% A$ Chilled grain Chilled Australia Tendon Other Frozen grass Frozen 10% 65 71% Tail 17% countries million Frozen grain 84% Kidney 67% Other Total 303,283 tonnes swt Total A$2.83 billion Total 29,687 tonnes swt China has rapidly become Australia’s single largest export destination for both lamb and mutton. -

China Case Study

【Panel VI : Paper 12】 China Case Study The Me-Generation or Agent of Political Change? Democratic Citizenship and Chinese Young Adults Organized by the Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica (IPSAS) Co-sponsored by Asian Barometer Survey September 20-21, 2012 Taipei IPSAS Conference Room A (5th floor, North, Building for Humanities and Social Sciences) China Case Study The Me-Generation or Agent of Political Change? Democratic Citizenship and Chinese Young Adults Jie Lu Department of Government, SPA, American University [email protected] This is only a rough draft. Please do not quote without author’s permission. Paper prepared for delivery at the conference “Democratic Citizenship and Voices of Asia’s Youth”, organized by the Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica, and co-sponsored by Asian Barometer Survey, National Taiwan University, September 20-21, 2012, Taipei, Taiwan. The Me-Generation or Agent of Political Change? Democratic Citizenship and Chinese Young Adults Jie Lu After their extensive and in-depth analysis of 40 blogs authored by young Chinese aged 18- 23 in 2006, Sima and Pugsley suggest the rise of a Me-culture among the Chinese youth, characterized by their symbolic identity construction and self-presentation based on individualism and consumerism.1 It is not a coincidence that, in his 2007 article published in the Time magazine, Simon Elegant presents the then youth generation (born after 1979) in mainland China as the Me-generation, who enjoys continuous economic prosperity, is obsessed with consumerism and new technologies, but shows little interest in politics and no enthusiasm for the social and political reforms that are necessary to ensure China’s long-term prosperity and stability.2 As he concludes the article, Elegant raises a serious question: How may this growing and increasingly powerful Me-generation shape China’s future? For Elegant, the answer is highly contingent upon whether the Me-generation realizes that political reforms and democracy can help China. -

China's Digital Nationalism and the Hong Kong Protests

China’s Digital Nationalism and the Hong Kong Protests An Interview with Florian Schneider by Emilie Frenkiel Nationalist discourses take the lion share of politics-related discussions on the Chinese Internet. In the context of intense struggles over the interpretation of the Hong Kong protests, this interview with Florian Schneider sheds light on the complexity of online political and identity expression in China and elsewhere. Florian Schneider, PhD, Sheffield University, is Senior University Lecturer in the Politics of Modern China at the Leiden University Institute for Area Studies. He is managing editor of the academic journal Asiascape: Digital Asia, director of the Leiden Asia Centre, and the author of three books: Staging China: the Politics of Mass Spectacle (Leiden University Press 2019), China’s Digital Nationalism (Oxford University Press 2018), and Visual Political Communication in Popular Chinese Television Series (Brill 2013, recipient of the 2014 EastAsiaNet book prize). In 2017, he was awarded the Leiden University teaching prize for his innovative work as an educator. His research interests include questions of governance, political communication, and digital media in China, as well as international relations in the East-Asian region. Books & Ideas: At the beginning of your book China’s Digital Nationalism, you wonder what happens when nationalism goes digital: how do you define digital nationalism? FS: To me, digital nationalism describes a process in which algorithms reproduce and enforce the kind of biases that lead people to view the nation as a major element of their personal identity and as the primary locus of political action. The biases themselves are much older than digital technology. -

China Transnationalized?

China Transnationalized? Allen Carlson Cornell University May 2015 Fellows Program on Peace, Governance, and Development in East Asia EAI Working Paper Knowledge-Net for a Better World The East Asia Institute(EAI) is a nonprofit and independent research organization in Korea, founded in May 2002. The EAI strives to transform East Asia into a society of nations based on liberal democracy, market economy, open society, and peace. The EAI takes no institutional position on policy issues and has no affiliation with the Korean government. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in its publications are the sole responsibility of the author or authors. is a registered trademark. Copyright © 2015 by EAI This electronic publication of EAI intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Copies may not be duplicated for commercial purposes. Unauthorized posting of EAI documents to a non-EAI website is prohibited. EAI documents are protected under copyright law. “China Transnationalized?” ISBN 979-11-86226-32-2 95340 The East Asia Institute #909 Sampoong B/D, Euljiro 158 Jung-gu, Seoul 100-786 Republic of Korea Tel. 82 2 2277 1683 Fax 82 2 2277 1684 Fellows Program on Peace, Governance, and Development in East Asia China Transnationalized?* Allen Carlson Cornell University May 2015 Introduction This paper, which is part of a larger research project, takes up the issue of contemporary China’s relationship with the rest of the world, and between its government and people. In so doing it challenges much of the conventional wisdom about China, both in terms of how to study the country, how it got to this juncture, and where it is headed. -

Regime Legitimacy and Comparative Chinese Secession Movements

POSC 289: Nationalism, Secession, and the State. Spring 2009, Dr. Thomas Julian Lee, Research Paper Regime Legitimacy and Comparative Chinese Secession Movements (PHOTO: A tattered PRC flag waves above a Beijing restaurant in the Xizhimen Wai District, 2001.) ABSTRACT: Much of foreigners’ “misunderstanding” of China is a result of its own environment of restricted information. An undeniably ideographic case, the current regime of the People’s Republic of China faces an ongoing crisis of legitimacy in its post-totalitarian state, to which its primary response has been the instrumental tapping of any and all potential sources, including vestigial socialist ideology, economic development, traditional Chinese culture, and perhaps most of all, a self-proclaimed status as the protector of a civic Chinese nation which may not actually exist. While denying its imperial past and present, the PRC seeks to construct such a nation, while retaining the territories and nations in its periphery which, due largely to non-identification as members of the Chinese nation, would prefer autonomy or independence by means of “secession”. Secessionist movements based on nationalist conflicts with the central government are unlikely to “succeed”, and as Chinese power rises, the more important issues are transparency and the types of tactics the Chinese Communist Party employs in pursuit of national integration. What all concerned parties must be vigilant for, additionally, is any evidence of a long-term strategy to reconstruct a “Sinocentric world” which would begin with the revisionist construction of a “Greater China”. China itself faces a choice of what kind of state it would prefer to be, and a primary indicator of its decision, by which the international community has judged it harshly, has been the policies toward “minority nationalities”, effectively denying their rights to self-determination, in turn denying the regime its desired legitimacy. -

Exploring the Perception of Nationalism in the United States and Saudi Arabia Reem Mohammed Alhethail Eastern Washington University

Eastern Washington University EWU Digital Commons EWU Masters Thesis Collection Student Research and Creative Works 2015 Exploring the perception of nationalism in the United States and Saudi Arabia Reem Mohammed Alhethail Eastern Washington University Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.ewu.edu/theses Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Alhethail, Reem Mohammed, "Exploring the perception of nationalism in the United States and Saudi Arabia" (2015). EWU Masters Thesis Collection. 330. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Creative Works at EWU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in EWU Masters Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of EWU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPLORING THE PERCEPTION OF NATIONALISM IN THE UNITED STATES AND SAUDI ARABIA A Thesis Presented To Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Master of Arts in History By Reem Mohammed Alhethail Fall 2015 ii THESIS OF REEM MOHAMMED ALHETHAIL APPROVED BY DATE ROBERT SAUDERS, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE DATE MICHAEL CONLIN, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE DATE CHADRON HAZELBAKER, GRADUATE STUDY COMMITTEE iii MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Eastern Washington University, I agree that (your library) shall make copies freely available for inspection. I further agree that copying of this project in whole or in part is allowable only for scholarly purposes. -

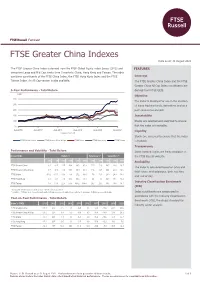

FTSE Greater China Indexes

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China Indexes Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China Index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS) and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks from 3 markets: China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The index combines constituents of the FTSE China Index, the FTSE Hong Kong Index and the FTSE Coverage Taiwan Index. An All Cap version is also available. The FTSE Greater China Index and the FTSE Greater China All Cap Index constituents are 5-Year Performance - Total Return derived from FTSE GEIS. (HKD) Objective 300 The index is designed for use in the creation 250 of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 200 performance benchmark. 150 Investability 100 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 50 that the index is investable. Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Liquidity Data as at month end Stocks are screened to ensure that the index FTSE Greater China FTSE Greater China All Cap FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan is tradable. Transparency Performance and Volatility - Total Return Index methodologies are freely available on Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE Greater China -8.1 -8.7 -1.7 10.4 38.5 81.0 11.5 12.6 18.5 20.6 16.7 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE Greater China All Cap -7.5 -7.6 -0.6 11.5 38.9 80.3 11.6 12.5 18.1 20.4 16.6 total return methodologies, both real time FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 and end of day. -

China Resilient, Sophisticated Authoritarianism

21st Century Authoritarians Freedom House Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Radio Free Asia JUNE 2009 FFH_UD7.inddH_UD7.indd iiiiii 55/22/09/22/09 111:221:22 AAMM CHINA RESILIENT, SOPHISTICATED AUTHORITARIANISM Joshua Kurlantzick Perry Link Chinese Communist Party leaders have clearly embraced the idea of soft power, and it has become central to their discourse about China’s role in the world. While only fi ve years ago Chinese offi cials and academics denied they had any lessons to offer to the developing world, today they not only accept this idea but use their training programs for foreign offi cials to promote aspects of the China model of development. introduction In 1989, in the wake of the crackdown on prodemocracy protesters in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, the moral and ideological standing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was at an all-time low. Popular complaints about corruption and special privileges for the elite were widespread. Idealistic language about socialism was seen as empty sloganeering. The Tiananmen killings showed that the “people’s army” could open fi re on the people themselves. China’s agricultural economy had been partially liberated, but the urban econ- omy still seemed locked within the iron framework of a work-unit system that was both ineffi cient and corrupt. No one either inside or outside China saw the country as a model for others. Now, nearly 20 years later, the prestige of the CCP has risen dramatically on the twin geysers of a long economic boom and a revived Han chauvinism. The expectation that more wealth in China would lead to more democracy (a fond hope in many foreign capitals) has been frustrated as one-party rule persists. -

China's Spring and Summer: the Tibet Demonstrations, the Sichuan Earthquake and the Bejing Olymic Games

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES AND JOHN L. THORNTON CHINA CENTER CHINA’S SPRING AND SUMMER: THE TIBET DEMONSTRATIONS, THE SICHUAN EARTHQUAKE AND THE BEJING OLYMIC GAMES The Brookings Institution Washington, DC July 8, 2008 Proceedings prepared from a tape recording by ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 P R O C E E D I N G S RICHARD BUSH: Ladies and gentlemen, thank you very much for coming. I’m Richard Bush, the director of the Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies here at Brookings. This event is co-sponsored by the John L. Thornton China Center. My colleague Jeffrey Bader is the director of that center, but he is on vacation. So, he’s here in virtual capacity. I must thank Orville Schell of the Asia Society for giving us this opportunity to have this event today. And we’re very grateful to that. I’m grateful to the staff of our two centers, and of our communications department for all their help. I think this is going to be a really interesting event. We are very fortunate and privileged to have James Miles with us today. He’s one of the most insightful and best informed reporters covering China today. He was the only Western reporter in Lhasa during the troubles of March. And he’s going to talk about that, in just a minute. He’s been in China for some time. He was first with the BBC. -

Scoring One for the Other Team

FIVE TURTLES IN A FLASK: FOR TAIWAN’S OUTER ISLANDS, AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE HOLDS A CERTAIN FATE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES MAY 2018 By Edward W. Green, Jr. Thesis Committee: Eric Harwit, Chairperson Shana J. Brown Cathryn H. Clayton Keywords: Taiwan independence, offshore islands, strait crisis, military intervention TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Scope and Organization ........................................................................................... 6 III. Dramatis Personae: The Five Islands ...................................................................... 9 III.1. Itu Aba ..................................................................................................... 11 III.2. Matsu ........................................................................................................ 14 III.3. The Pescadores ......................................................................................... 16 III.4. Pratas .......................................................................................................