Cross-Strait Relations and Implications for Northeast Asia: Views from the Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Taiwan History: Interpreting the Past in the Global Present

EATS III Paris, 2006 Writing Taiwan History: Interpreting the Past in the Global Present Ann Heylen Research Unit on Taiwanese Culture and Literature, Ruhr University Bochum [email protected] Do not cite, work in progress Introduction Concurrent with nation building is the construction of a national history to assure national cohesion. Hence, the collective memory is elevated to the standard of national myth and most often expressed in the master narrative. I may refer here to Michael Robinson’s observation that “the state constructs and maintains a ‘master narrative’ of nation which acts as an official ‘story of the nation’. This master narrative legitimates the existence of the state and nation internally; it is also projected externally, to legitimate a nations’ existence in the world community”.1 But in as much as memory is selective, so also is the state-sanctioned official narrative, and it has become commonplace that changes in the political order enhance and result in ideologically motivated re-writing of that history in spite of its claims at objectivity and truth. The study of the contemporary formation of Taiwan history and its historiography is no exception. In fact, the current activity in rewriting the history is compounded by an additional element, and one which is crucial to understanding the complexity of the issue. What makes Taiwanese historiography as a separate entity interesting, intriguing and complex is that the master-narrative is treated as a part of and embedded in Chinese history, and at the same time conditioned by the transition from a perceived to a real pressure from a larger nation, China, that lays claim on its territory, ethnicity, and past. -

Greater China: the Next Economic Superpower?

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Murray Weidenbaum Publications Government, and Public Policy Contemporary Issues Series 57 2-1-1993 Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower? Murray L. Weidenbaum Washington University in St Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers Part of the Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Weidenbaum, Murray L., "Greater China: The Next Economic Superpower?", Contemporary Issues Series 57, 1993, doi:10.7936/K7DB7ZZ6. Murray Weidenbaum Publications, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/mlw_papers/25. Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy — Washington University in St. Louis Campus Box 1027, St. Louis, MO 63130. Other titles available in this series: 46. The Seeds ofEntrepreneurship, Dwight Lee Greater China: The 47. Capital Mobility: Challenges for Next Economic Superpower? Business and Government, Richard B. McKenzie and Dwight Lee Murray Weidenbaum 48. Business Responsibility in a World of Global Competition, I James B. Burnham 49. Small Wars, Big Defense: Living in a World ofLower Tensions, Murray Weidenbaum 50. "Earth Summit": UN Spectacle with a Cast of Thousands, Murray Weidenbaum Contemporary 51. Fiscal Pollution and the Case Issues Series 57 for Congressional Term Limits, Dwight Lee February 1993 53. Global Warming Research: Learning from NAPAP 's Mistakes, Edward S. Rubin 54. The Case for Taxing Consumption, Murray Weidenbaum 55. Japan's Growing Influence in Asia: Implications for U.S. Business, Steven B. Schlossstein 56. The Mirage of Sustainable Development, Thomas J. DiLorenzo Additional copies are available from: i Center for the Study of American Business Washington University CS1- Campus Box 1208 One Brookings Drive Center for the Study of St. -

Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018)

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Spring 5-18-2018 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross- Strait Relations Jing Feng [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Recommended Citation Feng, Jing, "Contending Identities: Taiwan and China's Cross-Strait Relations" (2018). Master's Projects and Capstones. 777. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/777 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Contending Identities: Taiwan and China’s Cross-Strait Relationship Jing Feng Capstone Project APS 650 Professor Brian Komei Dempster May 15, 2018 2 Abstract Taiwan’s strategic geopolitical position—along with domestic political developments—have put the country in turmoil ever since the post-Chinese civil war. In particular, its antagonistic, cross-strait relationship with China has led to various negative consequences and cast a spotlight on the country on the international diplomatic front for close to over six decades. After the end of the Cold War, the democratization of Taiwan altered her political identity and released a nation-building process that was seemingly irreversible. Taiwan’s nation-building efforts have moved the nation further away from reunification with China. -

Greater China Beef & Sheepmeat Market Snapshot

MARKET SNAPSHOT l BEEF & SHEEPMEAT Despite being the most populous country in the world, the proportion of Chinese consumers who can regularly afford to buy Greater China high quality imported meat is relatively small in comparison to more developed markets such as the US and Japan. However, (China, Hong Kong and Taiwan) continued strong import demand for premium red meat will be driven by a significant increase in the number of wealthy households. Focusing on targeted opportunities with a differentiated product will help to build preference in what is a large, complex and competitive market. Taiwan and Hong Kong are smaller by comparison but still important markets for Australian red meat, underpinned by a high proportion of affluent households. China meat consumption 1 2 Population Household number by disposable income per capita3 US$35,000+ US$75,000+ 1,444 13% million 94.3 23% 8% 50 kg 56% 44.8 China grocery spend4 10.6 24.2 3.3 5.9 million million 333 26 3.0 51 16.1 Australia A$ Australia Korea China Korea Australia China US US China US Korea 1,573 per person 1,455 million by 2024 5% of total households 0.7% of total households (+1% from 2021) (9% by 2024) (1% by 2024) Australian beef exports to China have grown rapidly, increasing 70-fold over the past 10 years, with the country becoming Australia’s largest market in 2019. Australian beef Australian beef Australia’s share of Australian beef/veal exports – volume5 exports – value6 direct beef imports7 offal cuts exports8 4% 3% 6% 6% 3% Tripe 21% 16% Chilled grass Heart 9% A$ Chilled grain Chilled Australia Tendon Other Frozen grass Frozen 10% 65 71% Tail 17% countries million Frozen grain 84% Kidney 67% Other Total 303,283 tonnes swt Total A$2.83 billion Total 29,687 tonnes swt China has rapidly become Australia’s single largest export destination for both lamb and mutton. -

Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO Qingjiang Kong

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Journal of International Law 2005 Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO Qingjiang Kong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kong, Qingjiang, "Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What Are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO" (2005). Minnesota Journal of International Law. 220. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjil/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Journal of International Law collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cross-Taiwan Strait Relations: What are the Legitimate Expectations from the WTO? Qingjiang Kong* INTRODUCTION On December 11, 2001, China acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO).1 Taiwan followed on January 1, 2002 as the "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu."2 Accession of both China and Taiwan to the world trading body has triggered a fever of activities by Taiwanese businesses, but the governments on both sides of the Taiwan Strait have been slow to make policy adjustments. The coexis- tence of business enthusiasm and governmental indifference * Professor of International Economic Law, Zhejiang Gongshang University (previ- ously: Hangzhou University of Commerce), China. His recent book is China and the World Trade Organization:A Legal Perspective (New Jersey, London, Singapore, Hong Kong, World Scientific Publishing, 2002). Questions or comments may be e- mailed to Professor Kong at [email protected]. -

China As a Hybrid Influencer: Non-State Actors As State Proxies COI HYBRID INFLUENCE COI

Hybrid CoE Research Report 1 JUNE 2021 China as a hybrid influencer: Non-state actors as state proxies COI HYBRID INFLUENCE COI JUKKA AUKIA Hybrid CoE Hybrid CoE Research Report 1 China as a hybrid influencer: Non-state actors as state proxies JUKKA AUKIA 3 Hybrid CoE Research Reports are thorough, in-depth studies providing a deep understanding of hybrid threats and phenomena relating to them. Research Reports build on an original idea and follow academic research report standards, presenting new research findings. They provide either policy-relevant recommendations or practical conclusions. COI Hybrid Influence looks at how state and non-state actors conduct influence activities targeted at Participating States and institutions, as part of a hybrid campaign, and how hostile state actors use their influence tools in ways that attempt to sow instability, or curtail the sovereignty of other nations and the independence of institutions. The focus is on the behaviours, activities, and tools that a hostile actor can use. The goal is to equip practitioners with the tools they need to respond to and deter hybrid threats. COI HI is led by the UK. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats tel. +358 400 253 800 www.hybridcoe.fi ISBN (web) 978-952-7282-78-6 ISBN (print) 978-952-7282-79-3 ISSN 2737-0860 June 2021 Hybrid CoE is an international hub for practitioners and experts, building Participating States’ and institutions’ capabilities and enhancing EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats, located in Helsinki, Finland. The responsibility for the views expressed ultimately rests with the authors. -

Reinforcing the U.S.-Taiwan Relationship

Reinforcing the U.S.-Taiwan Relationship Testimony before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Asia and the Pacific United States House of Representatives Mark Stokes Executive Director The Project 2049 Institute Tuesday, April 17, 2018 Mr. Chairman and esteemed subcommittee members, thank you for the opportunity to testify today alongside my two distinguished colleagues. My remarks address the United States and future policy options in the Taiwan Strait. With the inauguration of President Tsai Ing-wen and the administration of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in May 2016, the Republic of China (Taiwan) completed its third peaceful transition of presidential power and the first transfer of power within its legislature in history. Since that time, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and its ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have sought to further isolate Taiwan internationally and coerce its democratically-elected government militarily. Panama and Sao Tome and Príncipe's abrupt shifts in diplomatic relations from the ROC to PRC are recent examples. Authorities in Beijing also have leveraged their financial influence to shut Taiwan out of international organizations, such as the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), and the International Criminal Police Organization (INTERPOL), among others. Tourists holding ROC passports are denied entry into the United Nations. The Chinese Communist Party has long sought the political subordination of people on Taiwan under its formula for unification -- “One Country, Two Systems.” Under this so- called “One China Principle,” there is One China, Taiwan is part of China, and the PRC is the sole representative of China in the international community. -

Communists Take Power in China

2 Communists Take Power in China MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES REVOLUTION After World War II, China remains a Communist •Mao Zedong • Red Guards Chinese Communists defeated country and a major power in • Jiang Jieshi • Cultural Revolution Nationalist forces and two the world. • commune separate Chinas emerged. SETTING THE STAGE In World War II, China fought on the side of the victo- rious Allies. But the victory proved to be a hollow one for China. During the war, Japan’s armies had occupied and devastated most of China’s cities. China’s civilian death toll alone was estimated between 10 to 22 million persons. This vast country suffered casualties second only to those of the Soviet Union. However, conflict did not end with the defeat of the Japanese. In 1945, opposing Chinese armies faced one another. TAKING NOTES Communists vs. Nationalists Recognizing Effects Use a chart to identify As you read in Chapter 14, a bitter civil war was raging between the Nationalists the causes and effects and the Communists when the Japanese invaded China in 1937. During World of the Communist War II, the political opponents temporarily united to fight the Japanese. But they Revolution in China. continued to jockey for position within China. Cause Effect World War II in China Under their leader, Mao Zedong (MOW dzuh•dahng), 1. 1. the Communists had a stronghold in northwestern China. From there, they mobi- 2. 2. lized peasants for guerrilla war against the Japanese in the northeast. Thanks to 3. 3. their efforts to promote literacy and improve food production, the Communists won the peasants’ loyalty. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

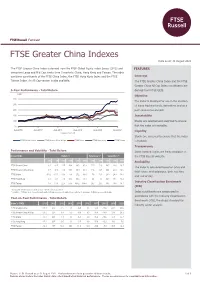

FTSE Greater China Indexes

FTSE Russell Factsheet FTSE Greater China Indexes Data as at: 31 August 2021 bmkTitle1 The FTSE Greater China Index is derived from the FTSE Global Equity Index Series (GEIS) and FEATURES comprises Large and Mid Cap stocks from 3 markets: China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. The index combines constituents of the FTSE China Index, the FTSE Hong Kong Index and the FTSE Coverage Taiwan Index. An All Cap version is also available. The FTSE Greater China Index and the FTSE Greater China All Cap Index constituents are 5-Year Performance - Total Return derived from FTSE GEIS. (HKD) Objective 300 The index is designed for use in the creation 250 of index tracking funds, derivatives and as a 200 performance benchmark. 150 Investability 100 Stocks are selected and weighted to ensure 50 that the index is investable. Aug-2016 Aug-2017 Aug-2018 Aug-2019 Aug-2020 Aug-2021 Liquidity Data as at month end Stocks are screened to ensure that the index FTSE Greater China FTSE Greater China All Cap FTSE China FTSE Hong Kong FTSE Taiwan is tradable. Transparency Performance and Volatility - Total Return Index methodologies are freely available on Index (HKD) Return % Return pa %* Volatility %** the FTSE Russell website. 3M 6M YTD 12M 3YR 5YR 3YR 5YR 1YR 3YR 5YR Availability FTSE Greater China -8.1 -8.7 -1.7 10.4 38.5 81.0 11.5 12.6 18.5 20.6 16.7 The index is calculated based on price and FTSE Greater China All Cap -7.5 -7.6 -0.6 11.5 38.9 80.3 11.6 12.5 18.1 20.4 16.6 total return methodologies, both real time FTSE China -13.2 -17.0 -11.6 -3.9 25.2 63.4 7.8 10.3 23.3 24.0 19.0 and end of day. -

Chen Muddies Cross-Strait Waters

China-Taiwan Relations: Chen Muddies Cross-Strait Waters by David G. Brown Associate Director, Asian Studies The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies On Aug. 3, President Chen Shui-bian told a video conference with independence supporters in Tokyo that there was “one country on each side” of the Taiwan Strait. Taiwan government officials, Washington, and Beijing were caught by surprise and concerned. Taipei quickly sent out assurances that policy has not changed, Washington reiterated that it did not support independence, and President Chen refrained from repeating this remark publicly. While no crisis occurred, the remarks appear in part to reflect Chen’s conclusion that Beijing’s cool response to Taipei’s goodwill offers means there is little near-term prospect for progress on cross-Strait issues. Taipei has pressed ahead with efforts to strengthen ties with the U.S., but its efforts to increase Taiwan’s international standing have suffered setbacks. Minor steps continue to be taken to ease restrictions on cross-Strait economic ties, which are again expanding rapidly. “Three Links” in Limbo This quarter opened with considerable attention on both sides of the Strait to ways the recently concluded extension of the Taiwan-Hong Kong Air Services Agreement could provide a model for how private groups might handle the opening of direct travel across the Strait − the so-called “three links.” President Chen seemed intent on opening direct travel before the 2004 presidential elections in order to demonstrate his ability to successfully manage cross-Strait relations. Bureaucrats in Taipei were working on the modalities for authorizing private groups to negotiate. -

I Want to Be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition

Volume 6 Issue 1 2020 “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan [email protected] ISSN: 2057-1720 doi: 10.2218/ls.v6i1.2020.4398 This paper is available at: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lifespansstyles Hosted by The University of Edinburgh Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan The years leading up to the political handover of Hong Kong to Mainland China surfaced issues regarding national identification and intergroup relations. These issues manifested in Hong Kong films of the time in the form of film characters’ language ideologies. An analysis of six films reveals three themes: (1) the assumption of mutual intelligibility between Cantonese and Putonghua, (2) the importance of English towards one’s Hong Kong identity, and (3) the expectation that Mainland immigrants use Cantonese as their primary language of communication in Hong Kong. The recurrence of these findings indicates their prevalence amongst native Hongkongers, even in a post-handover context. 1 Introduction The handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997 marked the end of 155 years of British colonial rule. Within this socio-political landscape came questions of identification and intergroup relations, both amongst native Hongkongers and Mainland Chinese (Tong et al. 1999, Brewer 1999). These manifest in the attitudes and ideologies that native Hongkongers have towards the three most widely used languages in Hong Kong: Cantonese, English, and Putonghua (a standard variety of Mandarin promoted in Mainland China by the Government).