Hevajra Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

Vasubandhu's) Commentary on His "Twenty Stanzas" with Appended Glossary of Technical Terms

AN INTRODUCTION AND TRANSLATION OF VINITADEVA'S EXPLANATION OF THE FIRST TEN VERSES OF (VASUBANDHU'S) COMMENTARY ON HIS "TWENTY STANZAS" WITH APPENDED GLOSSARY OF TECHNICAL TERMS Gregory Alexander Hillis Palo Alto, California B.A., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1979 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 1993 ABSTRACT In this thesis I argue that Vasubandhu categorically rejects the position that objects exist external to the mind. To support this interpretation, I engage in a close reading of Vasubandhu's Twenty Stanzas (Vif!lsatika, nyi shu pa), his autocommentary (vif!lsatika- vrtti, nyi shu pa'i 'grel pa), and Vinrtadeva's sub-commentary (prakaraiJa-vif!liaka-f'ika, rab tu byed pa nyi shu pa' i 'grel bshad). I endeavor to show how unambiguous statements in Vasubandhu's root text and autocommentary refuting the existence of external objects are further supported by Vinitadeva's explanantion. I examine two major streams of recent non-traditional scholarship on this topic, one that interprets Vasubandhu to be a realist, and one that interprets him to be an idealist. I argue strenuously against the former position, citing what I consider to be the questionable methodology of reading the thought of later thinkers such as Dignaga and Dharmak:Irti into the works of Vasubandhu, and argue in favor of the latter position with the stipulation that Vasubandhu does accept a plurality of separate minds, and he does not assert the existence of an Absolute Mind. -

Buddhist Backgrounds of the Burmese Revolution Buddhist Backgrounds Ofthe Burmese Revolution

BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OF THE BURMESE REVOLUTION BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OFTHE BURMESE REVOLUTION by E. SARKISYANZ PH.D. apl. Professor Freiburg University PREFACE BY DR. PAUL MUS Professor at the College de France and Yale University • Springer-Science+Business Media, B.Y. I965 Dedicated to the memory 01 my unlorgettable teacher ARNOLD BERGSTRAESSER ISBN 978-94-017-5830-7 ISBN 978-94-017-6283-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-6283-0 Copyright I965 by Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form Originally published by Martinus Nijhoff in 1965. Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by PAUL Mus. VII Foreword ..... XXIII Abbreviations . XXVII I. The Buddhist tradition of Burma's history . I 11. Buddhist traditions about a perfect society, its decline and the origin of the state . .. 10 III. Republican institutions in pre-Buddhist India and in the Buddhist order. .. 17 IV. The Buddhist welfare state of Ashoka. .. 26 v. Survival of Ashokan social and political traditions in Theravada kingship . .. 33 VI. On the problem of social ethics of Theravada Buddhism 37 VII. Emergence of the Bodhisattva ideal of kingship in Theravada Buddhism . .. 43 VIII. Pre-Buddhist fertility elements of the charisma of Burmese kingship . .. 49 IX. Economic implications of the Buddhist ideal of kingship 54 x. The Bodhisattva ideal of Burmese kingship . .. 59 XI. Kamma and Buddhist merit-causality as rationale for medieval Burma's social order . .. 68 XII. Buddhist ethics against the pragmatism of power under the Burmese kings. -

Getting to Know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE FOUR ORDERS: BOOK EXCERPT Getting to know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism hundreds ofyears that the four main been codified by Tibetan intellectual historians, who categorize Buddha's teachings in terms of three distinct of Tibetan Buddhism — Nyingma, vehicles — the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana), the Great Vehicle akya, and Gelug — have evolved out of (Mahayana), and the Vajra Vehicle (Vajrayana) — each of which was intended to appeal to the spiritual capacities of their common roots in India, a wide array of particular groups. divergent practices, beliefs, and rituals have • Hinayana was presented to people intent on personal salvation in which one transcends come into being. However, there are signifi- suffering and is liberated from cyclic existence. • The audience of Mahayana teachings included cant underlying commonalities between the trainees with the capacity to feel compassion for different traditions, such as the importance the sufferings of others who wished to seek awakening in order to help sentient beings over- of overcoming attachment to the phenomena come their sufferings. of cyclic existence, and the idea that it is • Vajrayana practitioners had a strong interest in the welfare of others, coupled with determination necessary for trainees to develop an attitude to attain awakening as quickly as possible, and the spiritual capacity to pursue the difficult practices of sincere renunciation. John Powers' fasci- of tantra. nating and comprehensive book, Introduction Indian Buddhism is also commonly divided by scholars of the four Tibetan orders into four main schools of tenets to Buddhism, re-issued by Snow Lion in — Great Exposition School, Sutra School, Mind Only School, September 2007, contains a lucid explanation and Middle Way School. -

Under Memberships

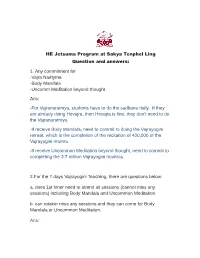

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Shankara: a Hindu Revivalist Or a Crypto-Buddhist?

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Religious Studies Theses Department of Religious Studies 12-4-2006 Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist? Kencho Tenzin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tenzin, Kencho, "Shankara: A Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/rs_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Religious Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHANKARA: A HINDU REVIVALIST OR A CRYPTO BUDDHIST? by KENCHO TENZIN Under The Direction of Kathryn McClymond ABSTRACT Shankara, the great Indian thinker, was known as the accurate expounder of the Upanishads. He is seen as a towering figure in the history of Indian philosophy and is credited with restoring the teachings of the Vedas to their pristine form. However, there are others who do not see such contributions from Shankara. They criticize his philosophy by calling it “crypto-Buddhism.” It is his unique philosophy of Advaita Vedanta that puts him at odds with other Hindu orthodox schools. Ironically, he is also criticized by Buddhists as a “born enemy of Buddhism” due to his relentless attacks on their tradition. This thesis, therefore, probes the question of how Shankara should best be regarded, “a Hindu Revivalist or a Crypto-Buddhist?” To address this question, this thesis reviews the historical setting for Shakara’s work, the state of Indian philosophy as a dynamic conversation involving Hindu and Buddhist thinkers, and finally Shankara’s intellectual genealogy. -

The Sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist Texts

Nepalese Culture Vol. XIII : 77-94, 2019 Central Department of NeHCA, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal The sacred Mahakala in the Hindu and Buddhist texts Dr. Poonam R L Rana Abstract Mahakala is the God of Time, Maya, Creation, Destruction and Power. He is affiliated with Lord Shiva. His abode is the cremation grounds and has four arms and three eyes, sitting on five corpse. He holds trident, drum, sword and hammer. He rubs ashes from the cremation ground. He is surrounded by vultures and jackals. His consort is Kali. Both together personify time and destructive powers. The paper deals with Sacred Mahakala and it mentions legends, tales, myths in Hindus and Buddhist texts. It includes various types, forms and iconographic features of Mahakalas. This research concludes that sacred Mahakala is of great significance to both the Buddhist and the Hindus alike. Key-words: Sacred Mahakala, Hindu texts, Buddhist texts. Mahakala Newari Pauwa Etymology of the name Mahakala The word Mahakala is a Sanskrit word . Maha means ‘Great’ and Kala refers to ‘ Time or Death’ . Mahakala means “ Beyond time or Death”(Mukherjee, (1988). NY). The Tibetan Buddhism calls ‘Mahakala’ NagpoChenpo’ meaning the ‘ Great Black One’ and also ‘Ganpo’ which means ‘The Protector’. The Iconographic features of Mahakala in Hindu text In the ShaktisamgamaTantra. The male spouse of Mahakali is the outwardly frightening Mahakala (Great Time), whose meditatative image (dhyana), mantra, yantra and meditation . In the Shaktisamgamatantra, the mantra of Mahakala is ‘Hum Hum Mahakalaprasidepraside Hrim Hrim Svaha.’ The meaning of the mantra is that Kalika, is the Virat, the bija of the mantra is Hum, the shakti is Hrim and the linchpin is Svaha. -

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature 4 1. Buddhist Tantric Literature Lama Anagarik Govinda wrote: “the word ‘Tantrd is related to the concept of weaving and its derivatives (thread, web, fabric, etc.), hinting at the interwovenness of things and actions, the interdependence of all that exists, the continuity in the interaction of cause and effect, as well as in spiritual and'traditional development, which like a thread weaves its way through the fabric of history and of individual lives. The scriptures which in Buddhism go under the name of Tantra (Tib.: rgyud) are invariably of a mystic nature, i.e., trying to establish the inner relationship of things: the parallelism of microcosm and macrocosm, mind and universe, ritual and reality, the world of matter and the world of the spirit.”99 Scholars like N.N. Bhattacharyya and also Pranabananda Jash, regard Tantra as a religious system or science (Sastra) dealing with the means (sadhana) of attaining success (siddhi) in secular or religious efforts.100 N.N. Bhattacharyya mentions that “Tantra came to mean the essentials of any religious system and, subsequently, special doctrines and rituals found only in certain forms of various religious systems. This change in the meaning, significance, and character of the word ‘Tantra' is quite striking and is likely to reveal many hitherto unnoticed elements that have characterised the social fabric of India through the ages.”101 It is must be noted that the Tantrika tradition is not the work of a day, it has a long history behind it. Creation, maintenance and dissolution, 99 Lama Anagarika Govinda, Foundations of Tibetan Myticism (Maine: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1969), p.93. -

Chinese and Tibetan Tantric Buddhism

THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM THE ISRAEL INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES International Research Conference of the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (IIAS) and the Israel Science Foundation with additional support from the Louis Freiberg Center for East Asian Studies and the Confucius Institute, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem CHINESE AND TIBETAN TANTRIC BUDDHISM June 16-18, 2014 All lectures will take place at the Feldman Building, on the Edmond J. Safra, Givat Ram Campus, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Organizers: Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University) Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University) PROGRAM Monday, June 16 9:30 Gathering 10:00 Greetings: Michal Linial (Director, IIAS) 10:30-12:00 ESOTERIC BUDDHISM AND CHINESE RELIGION Robert H. Sharf (University of California, Berkeley) Esoteric Buddhist Influence on the Emergence of Chan in Eighth Century China Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University & IIAS) The Tantric Origins of the Horse King: Hayagrīva and the Chinese Horse Cult Vincent Durand-Dastès (INALCO, Centre d’études chinoises, Equipe ASIEs, Paris) Esoteric Buddhism, Violence and Salvation in Ming-Qing Vernacular Novels 12:00-13:30 Lunch break 13:30-15:00 TIBETAN TANTRIC SCRIPTURES Jacob P. Dalton (University of California, Berkeley) Observations on the Ārya-tattvasaṃgraha-sādhanopāyikā and Its Commentary from Dunhuang Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem & IIAS) Conflicting Positions over the Interpretation of the Body Maṇḍala Jampa Samten (Central University for Tibetan Studies, Varanasi & IIAS) The Secret Signs (Chommaka) -

The Journal of the Walters Art Museum

THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 THE JOURNAL OF THE WALTERS ART MUSEUM VOL. 73, 2018 EDITORIAL BOARD FORM OF MANUSCRIPT Eleanor Hughes, Executive Editor All manuscripts must be typed and double-spaced (including quotations and Charles Dibble, Associate Editor endnotes). Contributors are encouraged to send manuscripts electronically; Amanda Kodeck please check with the editor/manager of curatorial publications as to compat- Amy Landau ibility of systems and fonts if you are using non-Western characters. Include on Julie Lauffenburger a separate sheet your name, home and business addresses, telephone, and email. All manuscripts should include a brief abstract (not to exceed 100 words). Manuscripts should also include a list of captions for all illustrations and a separate list of photo credits. VOLUME EDITOR Amy Landau FORM OF CITATION Monographs: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; italicized or DESIGNER underscored title of monograph; title of series (if needed, not italicized); volume Jennifer Corr Paulson numbers in arabic numerals (omitting “vol.”); place and date of publication enclosed in parentheses, followed by comma; page numbers (inclusive, not f. or ff.), without p. or pp. © 2018 Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 600 North Charles Street, Baltimore, L. H. Corcoran, Portrait Mummies from Roman Egypt (I–IV Centuries), Maryland 21201 Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 56 (Chicago, 1995), 97–99. Periodicals: Initial(s) and last name of author, followed by comma; title in All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written double quotation marks, followed by comma, full title of periodical italicized permission of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, Maryland. -

Self-Initiation Text

The Quick Path to Great Bliss: The Uncommon Sadhana of Venerable Vajrayogini Naro Khechari Together with the Self-Initiation Ritual, The Mandala Rite, Banquet of Great Bliss Arranged Simply and Clearly for the Sake of Easy Verbal Recitation Even if you have received [a highest yoga tantra] initiation and the blessing [initiation] of Vajrayogini, if you have not received the profound instructions on the two stages, refrain from reading this. With great respect, I prostrate to the feet of the guru, inseparable from Venerable Vajrayogini. With your great compassion, please care for me. A. Prepara@on Yogas 1, 2, and 3 To start, perform the first yoga of sleeping, the second yoga of waking, and the third yoga of tas@ng nectar. 4. Yoga of Immeasurables Sit with the physical essen@als [of the seven-fold posture] and recite: Dün gyi nam khar la ma khor lo dom pa yab yum la tsa gyü kyi la ma yi dam chhog sum ka dö sung mäi tshog kyi kor nä zhug par gyur In the space before me are Guru Chakrasamvara father and mother, encircled by the assemblies of root and lineage gurus, yidams, the Three Jewels, Dharma protectors, and guardians. Taking Refuge Imagine yourself and all sen@ent beings going for refuge: Dag dang dro wa nam khäi tha dang nyam päi sem chän tham chä dü di nä zung te ji si jang chhub nying po la chhi kyi bar du I and all living beings, equaling the limits of space, from now unAl reaching the essence of enlightenment, Päl dän la ma dam pa nam la kyab su chhi o Go for refuge to the glorious holy gurus; Dzog päi sang gyä chom dän dä nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the complete buddha bhagavans; Dam päi chhö nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the holy Dharma; Phag päi gen dün nam la kyab su chhi o (3x) We go for refuge to the arya Sangha. -

Reading the History of a Tibetan Mahakala Painting: the Nyingma Chod Mandala of Legs Ldan Nagpo Aghora in the Roy Al Ontario Museum

READING THE HISTORY OF A TIBETAN MAHAKALA PAINTING: THE NYINGMA CHOD MANDALA OF LEGS LDAN NAGPO AGHORA IN THE ROY AL ONTARIO MUSEUM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Aoife Richardson, B.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. John C. Huntington edby Dr. Susan Huntington dvisor Graduate Program in History of Art ABSTRACT This thesis presents a detailed study of a large Tibetan painting in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) that was collected in 1921 by an Irish fur trader named George Crofts. The painting represents a mandala, a Buddhist meditational diagram, centered on a fierce protector, or dharmapala, known as Mahakala or “Great Black Time” in Sanskrit. The more specific Tibetan form depicted, called Legs Idan Nagpo Aghora, or the “Excellent Black One who is Not Terrible,” is ironically named since the deity is himself very wrathful, as indicated by his bared fangs, bulging red eyes, and flaming hair. His surrounding mandala includes over 100 subsidiary figures, many of whom are indeed as terrifying in appearance as the central figure. There are three primary parts to this study. First, I discuss how the painting came to be in the museum, including the roles played by George Croft s, the collector and Charles Trick Currelly, the museum’s director, and the historical, political, and economic factors that brought about the ROM Himalayan collection. Through this historical focus, it can be seen that the painting is in fact part of a fascinating museological story, revealing details of the formation of the museum’s Asian collections during the tumultuous early Republican era in China.