Big and Small City Preferences of Migrant Workers in China: Case Studies of Beijing and Jinzhou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renao (Heat-Noise), Deities’ Efficacy, and Temple Festivals in Central and Southern Hebei Provincel

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Journal of Cambridge Studies 1 Renao (Heat-noise), Deities’ Efficacy, and Temple Festivals in Central and Southern Hebei Provincel Zhiya HUA School of Social Administration, Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, PRC [email protected] Abstract: There is a tradition of holding temple festivals in villages in central and southern Hebei Province. This tradition was once suspended after the establishment of P.R.C., but it revived and thrived after the reform and opening-up. Temple festivals are a kind of renao (热闹, heat-noise) events in rural life, and the organizers of temple festivals pursue the effect of renao as much as possible. Renao is a popular life condition welcomed by people; meanwhile, it can be regarded as an important exterior indicator of the efficacy of deities. Hence holding temple festivals and make renao at them provides an opportunity not only for people to experience and enjoy renao, but to acknowledge, publicize, and even produce the efficacy of deities. These sacred and secular rewards can partly account for the enduring resilience and vitality of the local tradition of holding temple festivals. Key Words: Temple festivals, Renao, Efficacy, Folk religion, Central and Southern Hebei Province This article is based on a part of the author’s Ph.D. dissertation. The author is grateful to Prof. Graeme Lang for his instruction and criticism. In addition, the author wants to thank Dr. Yue Yongyi for his criticism and help. This article is also one of the outcomes of a research project sponsored by Shanghai Pujiang Program (No. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Annual Report 2015

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Annual Report 2015 .suntien.com w ww Contents Chairman’s Statement 2 Corporate Profile 4 Financial Highlights and Major Operational Data 13 Management Discussion and Analysis 16 Human Resources 33 Biographies of Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 35 Report of the Board of Directors 41 Corporate Governance Report 59 Report of the Board of Supervisors 72 Independent Auditors’ Report 75 Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 77 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 78 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 80 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 81 Notes to Financial Statements 83 Definitions 180 Corporate Information 183 China Suntien Suntien Green Green Energy Energy Corporation Corporation Limited Limited Annual AnnualReport 2015 Report 2015 Chairman’s Statement 2 China Suntien Green Energy Corporation Limited Annual Report 2015 Chairman’s Statement Dear Shareholders, In 2015, due to the continual weakening of the global economic recovery and complicated economic situation, international trade contracted and financial risks increased. China’s economy was also at an unfavourable stage of “triple transition”, during which the economic growth decelerated with mounting downward pressure. In the meantime, the Company also faced with complicated and severe situations such as price reduction in wind power, declining demand of natural gas and difficulties encountered by infrastructure projects. The Board of Directors of the Company strived for making progress while maintaining stability, proactively responding to market changes and making preparations and plans so as to direct all employees to unite together and forge ahead. We also continued to speed up the process to seize market resources inside and outside the province, accelerated the progress of project construction and expanded the domestic and overseas financing channels, which greatly enhanced internal management and steadily optimized the business structure of the Company. -

Jinfan Zhang the Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law the Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law

Jinfan Zhang The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law Jinfan Zhang The Tradition and Modern Transition of Chinese Law Chief translator Zhang Lixin Other translators Yan Chen Li Xing Zhang Ye Xu Hongfen Jinfan Zhang China University of Political Science and Law Beijing , People’s Republic of China Sponsored by Chinese Fund for the Humanities and Social Sciences (本书获中华社会科学基金中华外译项目资助) ISBN 978-3-642-23265-7 ISBN 978-3-642-23266-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-23266-4 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014931393 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. -

Deities' Efficacy, and Temple Festivals in Central and Southern Hebei

Journal of Cambridge Studies 1 Renao (Heat-noise), Deities’ Efficacy, and Temple Festivals in Central and Southern Hebei Provincel Zhiya HUA School of Social Administration, Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, PRC [email protected] Abstract: There is a tradition of holding temple festivals in villages in central and southern Hebei Province. This tradition was once suspended after the establishment of P.R.C., but it revived and thrived after the reform and opening-up. Temple festivals are a kind of renao (热闹, heat-noise) events in rural life, and the organizers of temple festivals pursue the effect of renao as much as possible. Renao is a popular life condition welcomed by people; meanwhile, it can be regarded as an important exterior indicator of the efficacy of deities. Hence holding temple festivals and make renao at them provides an opportunity not only for people to experience and enjoy renao, but to acknowledge, publicize, and even produce the efficacy of deities. These sacred and secular rewards can partly account for the enduring resilience and vitality of the local tradition of holding temple festivals. Key Words: Temple festivals, Renao, Efficacy, Folk religion, Central and Southern Hebei Province This article is based on a part of the author’s Ph.D. dissertation. The author is grateful to Prof. Graeme Lang for his instruction and criticism. In addition, the author wants to thank Dr. Yue Yongyi for his criticism and help. This article is also one of the outcomes of a research project sponsored by Shanghai Pujiang Program (No. 13PJC099). Volume 8, No. -

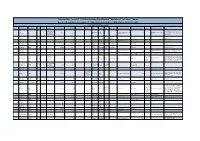

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps

Documented Cases of 1,352 Falun Gong Practitioners "Sentenced" to Prison Camps Based on Reports Received January - December 2009, Listed in Descending Order by Sentence Length Falun Dafa Information Center Case # Name (Pinyin)2 Name (Chinese) Age Gender Occupation Date of Detention Date of Sentencing Sentence length Charges City Province Court Judge's name Place currently detained Scheduled date of release Lawyer Initial place of detention Notes Employee of No.8 Arrested with his wife at his mother-in-law's Mine of the Coal Pingdingshan Henan Zhengzhou Prison in Xinmi City, Pingdingshan City Detention 1 Liu Gang 刘刚 m 18-May-08 early 2009 18 2027 home; transferred to current prison around Corporation of City Province Henan Province Center March 18, 2009 Pingdingshan City Nong'an Nong'an 2 Wei Cheng 魏成 37 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 18 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2027 Arrested from home; County Court Zhejiang Fuyang Zhejiang Province Women's 3 Jin Meihua 金美华 47 f 19-Nov-08 15 Fuyang City November, 2023 Province City Court Prison Nong'an Nong'an 4 Han Xixiang 韩希祥 42 m Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Nong'an Nong'an 5 Li Fengming 李凤明 45 m 27-Sep-07 27-Mar-09 14 Jilin Province County Guo Qingxi March, 2023 Arrested from home; County Court Arrested from home; detained until late April Liaoning Liaoning Province Women's Fushun Nangou Detention 6 Qi Huishu 齐会书 f 24-May-08 Apr-09 14 Fushun City 2023 2009, and then sentenced in secret and Province Prison Center transferred to current prison. -

And the Rule of Administrative Law in China

ADMINISTRATIVE “SELF-REGULATION” AND THE RULE OF ADMINISTRATIVE LAW IN CHINA Shen Kui* From a historical perspective, the formation and evolution of administrative law in many countries and regions have relied upon the important role and contribution of the judiciary. China is no exception in this respect. Over the past roughly thirty years, since the promulgation of the Administrative Litigation Law in 1989, Chinese courts have worked hard to secure the compliance of administrative actions with laws and regulations, and have acted as disguised lawmakers in fashioning new norms in regulating administrative agencies. The development of administrative law in China has also been propelled by legislation. The National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee have promulgated several laws regulating particular types of administrative action, such as administrative punishment, administrative licensing, and administrative compulsion, among others. Moreover, the NPC has passed many laws regulating specific areas of public administration, including but not limited to environmental protection, land administration, taxation, insurance, banking, and securities. In addition to making laws to regulate public administration, the legislature also monitors agencies’ statutory compliance through its “law enforcement inspection” power.1 * Professor, Peking University School of Law. I am very grateful to Neysun Mahboubi for his kind and helpful comments and edits on an earlier draft. I also am indebted to the comments from the participants of the 9th Administrative Law Discussion Forum at the Institutum Iurisprudentiae, Academia Sinica in Taipei on June 10-11, 2014, as well as the participants of the roundtable discussion centered on this special issue of the University of Pennsylvania Asia Law Review held at Peking University Law School in Beijing on June 21, 2014. -

The Nation-State, the Contract Responsibility System, and the Economy of Temple Incense: the Politics and Economics of a Temple Festival on a Landscaped Holy Mountain

Rural China: An International Journal of History and Social Science 13 (2016) 240-287 brill.com/rchs The Nation-State, the Contract Responsibility System, and the Economy of Temple Incense: The Politics and Economics of a Temple Festival on a Landscaped Holy Mountain Yongyi Yue* School of Chinese Language and Literature, Beijing Normal University, China [email protected] 民族国家、承包制与香火经济: 景区化圣山庙会的政治-经济学 岳永逸 Abstract Belief practices in mainland China have been subject to contracts as a result of a combination of factors: politics, economic growth, cultural development, and historic preservation. Thanks to the investigative reporting of the media, “contracting out belief” has lost all legitimacy on the level of politics, culture, religion, administration, and morality. The economy of temple incense has been re- lentlessly criticized for the same reason. In recent decades, Mount Cangyan, in Hebei, has changed from being a sacred site of pilgrimage to a landscaped tourist attraction. At the same time, the Mount Cangyan temple festival, which centers on the worship of the Third Princess, has gained legitimacy on a practical level. Conventional and newly emerged agents, such as beggars, charlatans, spirit me- diums, do-gooders, and contractors of the temple, are actively involved in the thriving temple fes- tival, competing, and sometimes cooperating, with each other. However, it is for the sake of maxi- mizing profit that landscaped Mount Cangyan under the contract responsibility system has been re-sanctified around the worship of the Third Princess along with other, new gods and attractions. The iconic temple festival on this holy mountain has influenced other temple festivals in various nearby * Yue Yongyi is a professor of the Institute of Folk Literature, School of Chinese Language and Lit- erature, Beijing Normal University, and an associate editor of the Cambridge Journal of China Studies. -

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins In

Urban Demolition and the Aesthetics of Recent Ruins in Experimental Photography from China Xavier Ortells-Nicolau Directors de tesi: Dr. Carles Prado-Fonts i Dr. Joaquín Beltrán Antolín Doctorat en Traducció i Estudis Interculturals Departament de Traducció, Interpretació i d’Estudis de l’Àsia Oriental Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2015 ii 工地不知道从哪天起,我们居住的城市 变成了一片名副其实的大工地 这变形记的场京仿佛一场 反复上演的噩梦,时时光顾失眠着 走到睡乡之前的一刻 就好像门面上悬着一快褪色的招牌 “欢迎光临”,太熟识了 以到于她也真的适应了这种的生活 No sé desde cuándo, la ciudad donde vivimos 比起那些在工地中忙碌的人群 se convirtió en un enorme sitio de obras, digno de ese 她就像一只蜂后,在一间屋子里 nombre, 孵化不知道是什么的后代 este paisaJe metamorfoseado se asemeja a una 哦,写作,生育,繁衍,结果,死去 pesadilla presentada una y otra vez, visitando a menudo el insomnio 但是工地还在运转着,这浩大的工程 de un momento antes de llegar hasta el país del sueño, 简直没有停止的一天,今人绝望 como el descolorido letrero que cuelga en la fachada de 她不得不设想,这能是新一轮 una tienda, 通天塔建造工程:设计师躲在 “honrados por su preferencia”, demasiado familiar, 安全的地下室里,就像卡夫卡的鼹鼠, de modo que para ella también resulta cómodo este modo 或锡安城的心脏,谁在乎呢? de vida, 多少人满怀信心,一致于信心成了目标 en contraste con la multitud aJetreada que se afana en la 工程质量,完成日期倒成了次要的 obra, 我们这个时代,也许只有偶然性突发性 ella parece una abeja reina, en su cuarto propio, incubando quién sabe qué descendencia. 能够结束一切,不会是“哗”的一声。 Ah, escribir, procrear, multipicarse, dar fruto, morir, pero el sitio de obras sigue operando, este vasto proyecto 周瓒 parece casi no tener fecha de entrega, desesperante, ella debe imaginar, esto es un nuevo proyecto, construir una torre de Babel: los ingenieros escondidos en el sótano de seguridad, como el topo de Kafka o el corazón de Sión, a quién le importa cuánta gente se llenó de confianza, de modo que esa confianza se volvió el fin, la calidad y la fecha de entrega, cosas de importancia secundaria. -

Hebei Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project

Resettlement Planning Document Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 40641 October 2008 People’s Republic of China: Hebei Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project Prepared by Urban Construction Investment Co. Ltd of Zhao County. The resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Zhaozhou Township Infrastructure Improvement Component Resettlement Plan Urban Construction Investment Co. Ltd. of Zhao County 1st October 2008 ENDORSEMENT LETTER FOR THE RESETTLEMENT PLAN With sufficient assistances from all sub-project units, we have prepared and compiled this Resettlement Plan (RP) for Zhaozhou Township Infrastructure Improvement Project. This RP is in accordance with relevant laws, policies and regulations of PRC, Hebei Province, Shijiazhuang City and Zhao County as well as the involuntary resettlement policies of Asian Development Bank. We endorse the actuality of the PR and have the commitment to the smooth implementation of land acquisition, house demolition, resettlement, compensation and budget. The PR is based on the Feasibility Study Report and the primary socio-economic survey. Once the project construction differs from the Feasibility Study Report and impacts on the implementation of the PR essentially, the PR should be revised timely and appropriately and reported to ADB for approval before its implementation. Chief Manager of Urban Construction -

Prevalence of Mobile Phones and Factors Influencing Usage by Caregivers of Young Children in Daily Life and for Health Care in Rural China: a Mixed Methods Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Prevalence of Mobile Phones and Factors Influencing Usage by Caregivers of Young Children in Daily Life and for Health Care in Rural China: A Mixed Methods Study Michelle Helena van Velthoven1☯,YeLi2☯, Wei Wang2, Li Chen2, Xiaozhen Du2, Qiong Wu2, Yanfeng Zhang2*, Igor Rudan3, Josip Car1 a11111 1 Global eHealth Unit, Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 2 Department of Integrated Early Childhood Development, Capital Institute of Paediatrics, Beijing, China, 3 Centre for Population Health Sciences and Global Health Academy, University of Edinburgh Medical School, Edinburgh, United Kingdom ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: van Velthoven MH, Li Y, Wang W, Chen L, Abstract Du X, Wu Q, et al. (2015) Prevalence of Mobile Phones and Factors Influencing Usage by Caregivers of Young Children in Daily Life and for Health Care in Introduction Rural China: A Mixed Methods Study. PLoS ONE To capitalise on mHealth, we need to understand the use of mobile phones both in daily life 10(3): e0116216. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116216 and for health care. Academic Editor: Don Operario, Brown University, UNITED STATES Objective Received: September 5, 2014 To assess the prevalence and factors that influence usage of mobile phones by caregivers Accepted: December 5, 2014 of young children. Published: March 19, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 van Velthoven et al. This is an Materials and Methods open access article distributed under the terms of the A mixed methods approach was used, whereby a survey (N=1854) and semi-structured in- Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any terviews (N=17) were conducted concurrently. -

Distribution, Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Aegilops Tauschii Coss. in Major Whea

Supplementary materials Title: Distribution, Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Aegilops tauschii Coss. in Major Wheat Growing Regions in China Table S1. The geographic locations of 192 Aegilops tauschii Coss. populations used in the genetic diversity analysis. Population Location code Qianyuan Village Kongzhongguo Town Yancheng County Luohe City 1 Henan Privince Guandao Village Houzhen Town Liantian County Weinan City Shaanxi 2 Province Bawang Village Gushi Town Linwei County Weinan City Shaanxi Prov- 3 ince Su Village Jinchengban Town Hancheng County Weinan City Shaanxi 4 Province Dongwu Village Wenkou Town Daiyue County Taian City Shandong 5 Privince Shiwu Village Liuwang Town Ningyang County Taian City Shandong 6 Privince Hongmiao Village Chengguan Town Renping County Liaocheng City 7 Shandong Province Xiwang Village Liangjia Town Henjin County Yuncheng City Shanxi 8 Province Xiqu Village Gujiao Town Xinjiang County Yuncheng City Shanxi 9 Province Shishi Village Ganting Town Hongtong County Linfen City Shanxi 10 Province 11 Xin Village Sansi Town Nanhe County Xingtai City Hebei Province Beichangbao Village Caohe Town Xushui County Baoding City Hebei 12 Province Nanguan Village Longyao Town Longyap County Xingtai City Hebei 13 Province Didi Village Longyao Town Longyao County Xingtai City Hebei Prov- 14 ince 15 Beixingzhuang Town Xingtai County Xingtai City Hebei Province Donghan Village Heyang Town Nanhe County Xingtai City Hebei Prov- 16 ince 17 Yan Village Luyi Town Guantao County Handan City Hebei Province Shanqiao Village Liucun Town Yaodu District Linfen City Shanxi Prov- 18 ince Sabxiaoying Village Huqiao Town Hui County Xingxiang City Henan 19 Province 20 Fanzhong Village Gaosi Town Xiangcheng City Henan Province Agriculture 2021, 11, 311.