Advertising and Public Relations Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Industry Haunted by Its Own History | 1

An Industry Haunted by Its Own History | 1 An Industry Haunted by Its Own History By Kerry Pechter Thu, Nov 1, 2018 The ghost of demutualization haunts much of the annuity industry today. But that topic was not on the agenda of the annual LIMRA conference in New York earlier this week (Photo: Former FBI director James Comey, the keynote speaker at the conference). Bob Kerzner, in his final address to the LIMRA membership after 14 popular years as their CEO, posed a perennial question: why hasn’t the life insurance industry capitalized on the Boomer retirement opportunity to the degree that it hoped, expected and, in its mind, deserved to? A complete answer to that question (which may stem in part from a post-demutualization misalignment of interests with the public) will fill a book someday (see note at end of story). Bob Kerzner Kerzner spoke at the annual LIMRA conference, which was held this year at the Marriott Marquis Hotel in New York. As the polyglot mass of tourists posed for snaps with the “Naked Cowboy” et al in Times Square below, a thousand or so dark-suited executives gathered soberly in the hotel ballrooms above. The conference was ornamented by the appearances of a celebrity guest speaker, former FBI director James Comey, and an inspirational TED talker, Simon Sinek (pronounced “cynic”). Both spoke of one’s duty to callings higher than achieving sales goals; both were also promoting new books. The most productive breakout session at the conference, for annuity issuers at least, may An Industry Haunted by Its Own History | 2 have been a discussion about potential synergies between various annuity industry stakeholders. -

North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library

North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library 355 Smoke Tree Business Park j North Aurora, IL 60542-1723 (630) 896-8860, x 108 j Fax (630) 896-4422 j WWW.NEMRT.COM j [email protected] The North East Multi-Regional Training Instructors Library In-Service Training Tape collection are available for loan to sworn law enforcement agencies in Illinois. Out-of-state law enforcement agencies may contact the Instructors Library about the possibility of arranging a loan. How to Borrow North East Multi-Regional Training In-Service Training Tapes How to Borrow Tapes: Call, write, or Fax NEMRT's librarian (that's Sarah Cole). Calling is probably the most effective way to contact her, because you can get immediate feedback on what tapes are available. In order to insure that borrowers are authorized through their law enforcement agency to borrow videos, please submit the initial lending request on agency letterhead (not a fax cover sheet or internal memo form). Also provide the name of the department’s training officer. If a requested tape is in the library at the time of the request, it will be sent to the borrower’s agency immediately. If the tape is not in, the borrower's name will be put on the tape's waiting list, and it will be sent as soon as possible. The due date--the date by which the tape must be back at NEMRT--is indicated on the loan receipt included with each loan. Since a lot of the tapes have long waiting lists, prompt return is appreciated not only by the Instructors' Library, but the other departments using the video collection. -

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

United States District Court Usdc Sdny Southern District of New York Document

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT USDC SDNY SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK DOCUMENT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x ELECTRONICALLY FILED DOC #: ___________________ ROBERT BURCK d/b/a THE NAKED : DATE FILED: __6/23/08_____ COWBOY, : Plaintiff, : OPINION - against - : 08 Civ. 1330 (DC) MARS, INCORPORATED and CHUTE GERDEMAN, INC., : Defendants. : - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x CHIN, District Judge This is the case of The Naked Cowboy versus The Blue M&M. Plaintiff Robert Burck is a "street entertainer" who performs in New York City's Times Square as The Naked Cowboy, wearing only a white cowboy hat, cowboy boots, and underpants, and carrying a guitar strategically placed to give the illusion of nudity. He has registered trademarks to "The Naked Cowboy" name and likeness. Beginning in April 2007, defendants Mars, Incorporated ("Mars") and Chute Gerdeman, Inc. ("Chute") began running an animated cartoon advertisement on two oversized video billboards in Times Square, featuring a blue M&M dressed "exactly like The Naked Cowboy," wearing only a white cowboy hat, cowboy boots, and underpants, and carrying a guitar. In this case, Burck sues defendants for compensatory and punitive damages. He alleges that defendants have violated his "right to publicity" under New York law and infringed his trademarks under federal law by using his likeness, persona, and image for commercial purposes without his written permission and by falsely suggesting that he has endorsed M&M candy. Three motions are before the Court: Chute moves pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6) to dismiss the complaint; Mars moves pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(c) for judgment on the pleadings; and Burck moves pursuant to Fed. -

Von Miller, Phillip Lindsay Selected to 2019 Pro Bowl; Three Broncos Tabbed As Alternates by Aric Dilalla Denverbroncos.Com December 19, 2018

Von Miller, Phillip Lindsay selected to 2019 Pro Bowl; Three Broncos tabbed as alternates By Aric DiLalla DenverBroncos.com December 19, 2018 Outside linebacker Von Miller and running back Phillip Lindsay have been selected to the 2019 Pro Bowl, the NFL announced Tuesday. Miller has now been selected to the Pro Bowl seven times, and he has been chosen every year since 2014. His 14.5 sacks this season are tied for second in the NFL. To read more about Miller’s Pro Bowl season, click here. Lindsay, meanwhile, becomes the first undrafted offensive rookie to earn a Pro Bowl bid. The Colorado product ranks in the top five in the NFL in rushing yards, rushing average and rushing touchdowns. He currently has 991 yards and nine touchdowns through 14 games. To read more about Lindsay’s Pro Bowl season, click here. The Broncos also had three players named alternates for the 2019 Pro Bowl. Cornerback Chris Harris Jr., wide receiver Emmanuel Sanders and outside linebacker Bradley Chubb were all tabbed as alternates. Harris tallied three interceptions, one sack and 49 tackles during his 12 starts in 2018. In Week 7, he returned one of those picks for a touchdown. He suffered a leg injury in Week 13 against the Bengals. Sanders, who suffered an Achilles injury in practice ahead of the Broncos’ game against the 49ers, tallied 71 catches for 868 yards and four receiving touchdowns. He also ran for a touchdown and caught a touchdown this season. The Broncos placed Sanders on IR ahead of their Week 14 game. -

9781317587255.Pdf

Global Metal Music and Culture This book defines the key ideas, scholarly debates, and research activities that have contributed to the formation of the international and interdisciplinary field of Metal Studies. Drawing on insights from a wide range of disciplines including popular music, cultural studies, sociology, anthropology, philos- ophy, and ethics, this volume offers new and innovative research on metal musicology, global/local scenes studies, fandom, gender and metal identity, metal media, and commerce. Offering a wide-ranging focus on bands, scenes, periods, and sounds, contributors explore topics such as the riff-based song writing of classic heavy metal bands and their modern equivalents, and the musical-aesthetics of Grindcore, Doom and Drone metal, Death metal, and Progressive metal. They interrogate production technologies, sound engi- neering, album artwork and band promotion, logos and merchandising, t-shirt and jewelry design, and the social class and cultural identities of the fan communities that define the global metal music economy and subcul- tural scene. The volume explores how the new academic discipline of metal studies was formed, while also looking forward to the future of metal music and its relationship to metal scholarship and fandom. With an international range of contributors, this volume will appeal to scholars of popular music, cultural studies, social psychology and sociology, as well as those interested in metal communities around the world. Andy R. Brown is Senior Lecturer in Media Communications at Bath Spa University, UK. Karl Spracklen is Professor of Leisure Studies at Leeds Metropolitan Uni- versity, UK. Keith Kahn-Harris is honorary research fellow and associate lecturer at Birkbeck College, UK. -

Law of Ideas, Revisted

The Law of Ideas, Revisited Lionel S. Sobel* NIMMER ON IDEAS ............................. 10 THE SEARCH FOR AN IDEA-PROTECTION LEGAL THEORY . 14 A. Historic Reasons for the Search ................. 14 B. Current Status of State Law Theories Providing Idea Protection ............................. 21 1. Theories That Continue to Be Useful ........... 21 a. Contract Law ........................ 21 b. Confidential Relationship Law ............. 23 2. Theories That Have Become Superfluous ........ 26 a. Property Law .............. .......... 26 b. Quasi-ContractLaw .......... .......... 28 c. Other Legal Theories ......... .......... 31 3. Conclusions on the Current Status of State Law Theories ........... .......... 32 III. ISSUES OF CURRENT IMPORTANCE ........ .......... 33 A. Conditions Creating an Obligation to Pay .......... 33 1. Circumstances Surrounding the Submission of the Idea ........... .......... 34 a. Obligations Resulting From Agreements ...... 34 (1) Express Agreements ................. 34 (2) Implied Agreements ................. 37 (a) Circumstances Creating Implied Agreements .............. 37 (b) The Role of Industry Custom ........ 44 * Professor, Loyola Law School (Los Angeles); Editor, ENTERTAINMENT LAW REPORTER. B.A. 1966, University of California, Berkeley; J.D. 1969, UCLA School of Law. Professor Sobel was co-counsel for Paramount Pictures Corporation during the trial court proceedings in the Buchwald v. ParamountPictures case discussed in this article. Copyright © 1994 by Lionel S. Sobel. 10 UCLA ENTERTAINMENT LAW -

Suzy & Los Quat T

Fecha Salida: 27 de Septiembre de 2011 Singles Recomendados: 7. I.O.U. (I Owe Yo u ) 6. In My Dreams Again 1. Freak Out 5. Kick Ass SUZY & LOS QUAT T R O HANK Lista de canciones: Wow, esto sí que es tomar algo negativo y convertirlo en positivo. 1. Freak Out 2. Don’t Wanna Talk About It En marzo de 2009, Suzy & Los Quattro perdieron a su gran amigo y road- ie HANK. Este hecho les catapultó en un episodio que han capturado 3. Move On como si se tratara de una película en audio. Dudo en utilizar el término 4. The Quiet Man "ópera rock" ya que este disco incluye grandes dosis de "roll". 5. Kick Ass 6. In My Dreams Again Además, aparte de tener que enfrentarse a la muerte de un amigo excep- 7. I.O.U. (I Owe Yo u ) cional, el proceso de aceptación tuvo múltiples subidas y bajadas. Todas 8. Love Never Dies ellas están documentadas aquí, tomando forma tras algo así como una 9. You Angel Yo u colisión entre lo más florido del punk de la costa este y el glorioso pop 10. Still Mad About Yo u californiano. 11. The Goodbye Song Hoy en día se vierten ríos de tinta sobre lo maravillosas que son ciertas bandas y artistas. La mayor parte es palabrería, pero tienen que vender- Puntos de interés: los de alguna forma. Yo levanto mi mano - estoy quizás algo sesgado pero - Producido por Robbie Rist (The Rubinoos, uno ha de intentar ser objetivo. Hay momentos en los que, para manten- Steve Barton, The Mockers) y grabado en los er algún tipo de credibilidad, tal sesgo debe ser mantenido a distancia ya estudios Musiclan (Figuere s ) que lo contrario perjudicaría tanto a la banda sobre la que se escribe como al individuo que testifica sobre ellos. -

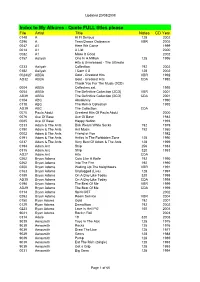

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance