Why German State and City Theatres Love Refugees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TT1617 SZH Web(1).Pdf

201 6 & 2 0 1 7 * Die Welt ist alles, was der Fall ist. Ludwig Wittgenstein Liebes Publikum 6 Premieren auf einen Blick8 Wiederaufnahmen10 Premieren14 Ensemble&Regie30 Um alles in der Welt – Lessingtage78 Theater der Welt86 Gastspiele88 A–Z90 jung&mehr 98 Service 101 Abos 104 Plätze&Preise 105 Kontakt108 Thalia Freunde109 Förderer&Partner110 8 Liebes Publikum, Das Festival „Um alles in der Welt – Lessingtage“ wird sich 2017 mit unseren eigenen Geburtsschmerzen befassen, die 1517 mit Martin Politik ist der Versuch, einen Konsens herzustellen, darüber, was eine Luther begannen. Gesellschaft als Kollektiv tun könnte. Dieser Konsens bricht immer Halbblind im Jetzt zu leben ist nichts Neues, nur die Schnittlinien des wieder auseinander und muss neu erkämpft werden. Je größer der Umbruchs sind jeweils verschieden. In Theodor Storms „Der Schimmel- Riss, desto größer sind die Auseinandersetzungen und Umbrüche. reiter“ kämpft der moderne faustische Mensch gegen den Aberglau- Theater lebt davon, von solchen Umbrüchen und Konflikten zu erzäh- ben und geht unter. Besonders nachdrücklich spiegelt sich gesell- len. Es ist die Charakteristik nahezu jeder Epoche, die eigene Gegen- schaftlicher Umbruch in Familiengeschichten. So erzählt Luk Percevals wart gewissermaßen blind zu erleben. Erst aus dem Abstand klärt große Émile Zola-Trilogie vom Aufstieg und Fall einer Familie in der zwei- sich, was da eigentlich war. Das Gefühl der Zeitgenossen trügt oder ten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, und die in Hamburg lebende Georgierin stimmt, man weiß es nicht. Nino Haratischwili blickt in ihrem Jahrhundertepos „Das achte Leben Das Thalia beginnt die Spielzeit mit drei Gegenwartsautoren und einem (Für Brilka)“ auf das gesamte 20. Jahrhundert von der Oktoberrevolu- Europa-Schwerpunkt: „Wut/Rage“ von Jelinek/Stephens im Großen tion bis heute – über sechs Generationen hinweg – aus der Perspekti- Haus und „Erschlagt die Armen!“ von Shumona Sinha in der Gaußstra- ve einer georgischen Familie. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit Terror und Theater. RAF-Stücke im Kontext von politischem und dokumentarischem Theater Verfasserin Brigitte Auer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil) Wien, im Oktober 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A332 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Deutsche Philologie Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Michael Rohrwasser 2 Ich danke Marina Gr!ini" für die Erkenntnis darüber, was es bedeutet, Position zu beziehen. Weiters danke ich Michael Rohrwasser für die Betreuung, Barbara Grasböck und Oliver Stangl für Lektorat und Zuspruch und den vielen Personen, die wissentlich oder unwissentlich zur Entstehung und Fertigstellung dieser Arbeit beigetragen haben. Vor allem aber danke ich meinen Eltern für ihre Unterstützung und Geduld während meiner Studienzeit. 3 4 Inhalt 1. Einleitung........................................................................................................S.7 2. Terrorismus....................................................................................................S.8 2.1. Schwierigkeiten.................................................................................S.8 2.2. Exkurs: Vorsicht (Teil I)..................................................................S.11 2.3. Begriffsgeschichte...........................................................................S.12 2.4. Formen des Terrorismus..................................................................S.13 -

Hamburg 2017 Around Town

Hamburg 2017 Around Town Tips and Information Welcome to the SWIB17 from 4 to 6 December 2017! Culture 5 Theatres 5 Opera, Ballet and Concerts 6 Musicals 6 Museums 7 Hamburg Sights 9 Highlights 9 Other sights well worth seeing 11 Hamburg Panorama – beautiful views 12 Restaurants 13 For epicures 17 Bars and Beach Clubs 18 Partying and Dancing in Hamburg 20 Hamburg Services 21 CULTURE Theatres Thalia Theater GmbH Kampnagel Hamburg Alstertor Jarrestr. 20 20095 Hamburg 22303 Hamburg T: +49 (0)40 328140 T: +49 (0)40 27094949 Home to one of Germany’s most The former factory is used as an famous ensembles which stages event location for the contemporary around nine new plays per season. performing arts. [email protected] [email protected] www.thalia-theater.de www.kampnagel.de Public transport: S1/S2/S3/U1/U2/U4 to Public transport: bus 172/173 to Jarrestraße Jungfernstieg Station Ohnsorg-Theater Thalia Theater Gaußstraße Heidi-Kabel-Platz 1 Gaußstraße 190 20099 Hamburg 22765 Hamburg T: +49 (0)40 35080321 T: +49 (0)40 306039-10, -12 The Ohnsorg-Theater is one of The small Thalia Theatre stages Hamburg’s most traditional thea- plays in a cosy atmosphere. The ac- tres. Hamburg dialect is spoken in tors are so close that you can almost every performance. reach out to them. [email protected] Contact: [email protected] www.ohnsorg.de www.thalia-theater.de Public transport: S/U to Hauptbahnhof Public transport: S1/S3/S11/S31 to Altona Station Station Deutsches Schauspielhaus Hamburg Kirchenallee 39 20099 Hamburg T: +49 (0)40 248713 One of Germany’s largest and most beautiful theatres for spoken drama. -

The Absence of Traditional Characters in Philippe Manoury's Thinkspiel Kein Licht

The absence of traditional characters in Philippe Manoury’s Thinkspiel Kein Licht. (2011/2012/2017) Eva Van Daele (Ghent University, September 2018) To this day, composers try to reinvent the genres of opera and music theatre. One of the impulses for renewal is contemporary theatre. One development we notice is a discrepancy between the singer and the character in contemporary music theatre (in its broadest form). This discrepancy is an opportunity to question how we (re)present voices, ourselves and our stories on stage. We will look at the phenomenon in one specific work. Our case Kein Licht. (2011/2012/2017) is a collaboration between the French composer Philippe Manoury (b. 1952) and German theatre director Nicolas Stemann (b. 1968) who created a performance based on theatre texts by Elfriede Jelinek. The main concern of this paper is this: how is the lack of characters in Jelinek’s text addressed in the Thinkspiel Kein Licht. (2011/2012/2017) of Nicolas Stemann and Philippe Manoury?1 This question is inseparable from the treatment and the allocation of text to the voices and bodies on stage. It is not immediately clear how the text of Jelinek is distributed among the speakers and if the words of actors and singers have a different status. Since nor in the theatre texts, nor in the Thinkspiel we can’t speak of “characters”, I will use the term “roles”. There is a friction between the “roles” (such as A and B) in the text, what we see on scene, and what we hear. Indeed, even between what we see and what we hear, concerning the actors and singers, we notice a discrepancy. -

Elfriede Jelineks Theater. Eine Analyse Des Königinnenduetts in Nicolas Stemanns Inszenierung Von Ulrike Maria Stuart.“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Elfriede Jelineks Theater. Eine Analyse des Königinnenduetts in Nicolas Stemanns Inszenierung von Ulrike Maria Stuart.“ Verfasserin Cara-Sophia Pirnat angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, Februar 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuerin: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Monika Meister Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 EINLEITUNG ............................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 SUBJEKTIVITÄT DER ANALYSE ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 CO-AUTORENSCHAFT ZWISCHEN AUTORIN UND REGISSEUR ........................................................ 5 1.3 ENTSTEHUNGSGESCHICHTE UND THEMATIK DES TEXTES ULRIKE MARIA STUART ......................... 6 1.4 FORSCHUNGSSTAND ...................................................................................................................... 9 1.5 REZEPTION DER INSZENIERUNG .................................................................................................. 10 1.6 METHODE UND PROBLEMATIK DER INSZENIERUNGSANALYSE .................................................... 11 2 REGIE: NICOLAS STEMANN ................................................................................................. 13 3 DIE INSZENIERUNG ............................................................................................................... -

Gründung Und Entwicklung Der Ruhrfestspiele in Recklinghausen*

Ingeborg Schnelling-Reinicke Gründung und Entwicklung der Ruhrfestspiele in Recklinghausen* Im Jahr 1965 wurde in Recklinghausen ein neues Festspielhaus fertiggestellt und eingeweiht. Es trägt folgende Inschrift: VOR DEN RUINEN DES VATERLANDES/VEREINTEN SICH IM JAHRE 1946 /BERG LEUTE UND KÜNSTLER/ ZU GEGENSEITIGER HILFE AUS DEM TAUSCHE/KOHLE GEGEN KUNST/KUNST GEGEN KOHLE/WUCHS FREUNDSCHAFT I ERSTANDEN DIE RUHRFESTSPIELE DIESES HAUS/IST EIN WERK DER DEMOKRATIE ES SOLL NACH DEM WORT/VON THEODOR HEUSS SEIN:/EINE HEIMAT DER MUSEN / EINE HERBERGE MENSCHLICHER BEGEGNUNGEN /UND EINE BURG FREIHEITLICHEN SEINS 1 In diesen wenigen Worten verdichtet sich der Mythos der Ruhrfestspiele, ihrer Gründung und ihr Auftrag. Die darin sehr verkürzt wiedergegebene Gründungsgeschichte der Fest spiele, wie sie seither immer wieder in dem Schlagwort "Kohle gab ich fiir Kunst - Kunst gab ich fiir Kohle" werbewirksam wiederholt wird, wurde im Jahr 1996, dem Jahr der 50. Ruhrfestspiele, in zahlreichen Veröffentlichungen, u. a. Fernseh- und Rundfunksendun gen ausruhrlieh präsentiert.2 Die folgenden Überlegungen wollen den Besonderheiten und Eigenarten der bis heute erfolgreichen Festspiele nachgehen. Sie werden sich auf die ersten beiden Jahrzehnte der Festspiele beschränken, den Zeitraum, an dessen Ende der Bau des Festspielhauses einen äußerlich sichtbaren Einschnitt in die Festspielgeschichte darstellt. Die Beschäftigung mit der Geschichte der Ruhrfestspiele lohnt sich, nicht nur, weil sie jetzt über 50 Jahre im großen und ganzen erfolgreich bestehen, sondern auch, weil sie ohne Vorgänger• institutionen, an die man hätte anknüpfen können, gegründet wurden. Sie bieten so die selte ne Gelegenheit, an einem Beispiel die Grundbedingungen und die wesentlichen Vorausset zungen fiir eine trotzdem erfolgreiche Gründung im Einzelnen kennen zu lernen. -

Redalyc.Von Schillers Ästhetischer Theorie Zur Dekonstruktion Und

Revista de Filología Alemana ISSN: 1133-0406 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España GIMÉNEZ CALPE, Ana Von Schillers ästhetischer Theorie zur Dekonstruktion und Entmythologisierung. Elfriede Jelineks / Nicolas Stemanns Ulrike Maria Stuart Revista de Filología Alemana, vol. 23, 2015, pp. 135-152 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Erhältlich in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321841408008 Wie zitieren Komplette Ausgabe Wissenschaftliche Informationssystem Mehr informationen zum Artikel Netzwerk von wissenschaftliche Zeitschriften aus Lateinamerika, der Karibik, Spanien und Zeitschrift Homepage in redalyc.org Portugal Wissenschaftliche Non-Profit-Projekt, unter der Open-Access-Initiative Von Schillers ästhetischer Theorie zur Dekonstruktion und Entmythologisierung. Elfriede Jelineks / Nicolas Stemanns Ulrike Maria Stuart Ana GIMÉNEZ CALPE Universitat de València [email protected] Recibido: 3 de septiembre de 2014 Aceptado: 20 de noviembre de 2014 ZUSAMMENFASSUNG Wie die meisten Texte Elfriede Jelineks ist auch das Theaterstück Ulrike Maria Stuart reich an intertextuellen Referenzen. Neben Schillers Trauerspiel Maria Stuart werden unter anderem Texte aus den Schriften der RAF (Rote Armee Fraktion) so wie aus journalistischen Veröffentlichungen über die terroristische Vereinigung zitiert, paraphrasiert und umformuliert. Dieser Artikel geht der Frage nach, wie die intertextuellen Referenzen in Jelineks polyphonem Text eine idealistische Auf- fassung der Welt und der Kunst, die in den in Ulrike Maria -

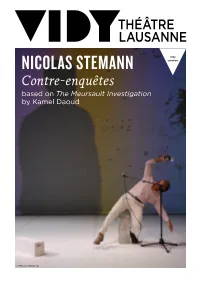

NICOLAS STEMANN Creation Contre-Enquêtes Based on the Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud

Vidy NICOLAS STEMANN creation Contre-enquêtes based on The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud © Philippe Weissbrodt CONTENTS 2 DISTRIBUTION 3 PRESENTATION 4 HOW LITERATURE CAN ACT AGAINST CYNICISM THE THEATRE OF NICOLAS STEMANN 5 TEASER 7 MEETING THE STRANGER 8 “THE PRESENT ONLY EXISTS BECAUSE ONE MAN REMEMBERS IT” 11 BEYOND THE SHOW 12 NICOLAS STEMANN 13 MOUNIR MARGOUM 14 THIERRY RAYNAUD 15 KAMEL DAOUD 16 PALOMA COLOMBE 17 KATINKA DEECKE 18 CLAUDIA LEHMANN 19 MARYSOL DEL CASTILLO 20 CONTACTS 21 DISTRIBUTION 3 Vidy Contre-enquêtes creation based on The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud Length: ~1:20 Theatre English surtitles available Conception, adaptation, scenography Nicolas Stemann Video Claudia Lehmann Costumes Marysol del Castillo Sound creation Paloma Colombe Nicolas Stemann Light creation Jonathan O’Hear Dramaturgy Katinka Deecke Assistant to the director Mathias Brossard With Mounir Margoum Thierry Raynaud Production Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne Schauspielhaus Zürich The Cercle des mécènes du Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne supports the Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne for this show. With the support of the production, technical, communication and administration teams of Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne BACK TO Creation 2020 CONTENTS PRESENTATION 4 With this new creation, German director Nicolas Stemann has taken the novel that was to demonstrate the incisive writing of Algerian Kamel Daoud to the world, complemented with other texts. This Algerian author, today one of the most unique voices in Francophone literature, is known for his strong stand against religious radicalisation, as well as against post-colonial hypocrisy. He positions himself in the breach that writing provides, pointing out hypocrisy and responsibility in the West as well as in the Muslim world. -

Elfriede Jelinek's Die Schutzbefohlenen

Elfriede Jelinek’s Die Schutzbefohlenen : A chorus of complaints on human rights catastrophes I. Refugees Twenty-eight fugitives escaping from the eastern shore of Maryland is a painting that was published in 1872 in the book The Underground Railroad (Philadelphia, Porter & Coates, 1872), written by William Still. William Still lived in Philadelphia, where he was chairman of the Vigilance Committee of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. He aided fugitive slaves by means of the so-called Underground Railroad and kept records of their lives in order to help families reunite after slavery was abolished. Elfriede Jelinek’s theater text Die Schutzbefohlenen begins with that image. First published in internet on June 14 th , 2013, the text was later modified by herself in November 2013 and again in November 2014. Jelinek, who was born in 1946 in a small Austrian village, had her literary breakthrough in 1975 with die liebhaberinnen , a marxist-feminist caricature of a homeland-novel. Since then, Jelinek writes against drawbacks in both public-political and private live – mainly, but not only of the Austrian society: Babel (2005) for example is a theater text on the war in Iraq and the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse. In 2004, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for her »musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that, with extraordinary linguistic zeal, reveal the absurdity of society's clichés and their subjugating power. «1 Considering the literature market of the German speaking countries to be extremely bankrupt and nepotistic, she decided recently to publish her writings exclusively on her own website. -

The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud, and Other Texts

THÉÂTRE VIDY-LAUSANNE AV. E.-H. JAQUES-DALCROZE 5 CH-1007 LAUSANNE Creation NICOLAS STEMANN at Vidy Contre-enquêtes based on The Meursault Investigation by Kamel Daoud, and other texts © DR NICOLAS STEMANN CONTRE-ENQUÊTES 2 CONTACTS THÉÂTRE VIDY-LAUSANNE DIRECTION: VINCENT BAUDRILLER PRODUCTION: DIRECTOR OF ARTISTIC AND INTERNATIONAL PROJECTS CAROLINE BARNEAUD [email protected] T +41 (0)21 619 45 44 TECHNICS: TECHNICAL DIRECTION CHRISTIAN WILMART / SAMUEL MARCHINA [email protected] T +41 (0)21 619 45 16 / 81 PRESS: DIRECTOR OF AUDIENCES AND COMMUNICATION ASTRID LAVANDEROS [email protected] T +41 (0)21 619 45 74 M +41 (0)79 949 46 93 COMMUNICATION ASSISTANT PAULINE AMEZ-DROZ [email protected] T +41 (0)21 619 45 21 Creation NICOLAS STEMANN CONTRE-ENQUÊTES 3 at Vidy DISTRIBUTION Conception, adaptation, scenography : Nicolas Stemann Assistant to the director : Mathias Brossard Video : Claudia Lehmann Costumes : Marysol del Castillo Dramaturgy : Katinka Deecke With : Mounir Margoum Thierry Raynaud Production : Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne Schauspielhaus Zürich Creation March 2020 NICOLAS STEMANN CONTRE-ENQUÊTES 4 PRESENTATION This time as a starting point, the German director has taken the novel that was to demonstrate the incisive writing of Algerian Kamel Daoud to the world, probably complemented with other texts. This Algerian author, today one of the most unique voices in Francophone literature, is known for his strong stand against religious radicalisation, as well as against post-colonial hypocrisy. He positions himself in the breach that writing provides, pointing out hypocrisy and responsibility in the West as well as in the Muslim world. In his novel, Kamel Daoud gives voice to the alleged brother of the Arab killed by Meursault, the hero of The Stranger by Camus. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRAPHY Abdilla, R. (2016) ‘Local Artistic Produce (3): Lampedusa’, 17 March. http:// whenpraxisbecomesunbearable.tumblr.com/post/141197850957/local-artis- tic-produce-3-lampedusa, date accessed 13 March 2017. ACP (2012) Contemporary Catholic Perspectives. http://www.associationof- catholicpriests.ie/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Contemporary-Catholic- Perspectives.pdf, date accessed 26 February 2017. Aeschylus. (1992) ‘The Suppliant Maidens’, trans. S.G. Benardete in D. Grene and R. Lattimore (eds) Aeschylus II (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). Agamben, G. (1995) ‘We Refugees’, trans. Michael Rocke, Symposium, 49 (2), 114–119. http://www.faculty.umb.edu/gary_zabel/Courses/Phil%20108- 08/We%20Refugees%20-%20Giorgio%20Agamben%20-%201994.htm, date accessed 15 February 2017. Agamben, G. (1998) Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford: Stanford University Press). Agamben, G. (2005) State of Exception, trans. K. Attell (Chicago: Chicago University Press). Agee, P. (1975) Inside the Company: CIA Diary (Penguin Books). AIDA (2016) ‘Country Report: Ireland’. http://www.asylumineurope.org/ sites/default/files/report-download/aida_ie_update.v_final.pdf, date accessed 1 April 2017. Anderson, P. (2003) ‘Over 100,000 Protest Against War in Dublin and Belfast’, Irish Times, 15 February. http://www.irishtimes.com/news/over-100-000- protest-against-war-in-dublin-and-belfast-1.461812, date accessed 27 February 2017. © The Author(s) 2018 213 S.E. Wilmer, Performing Statelessness in Europe, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69173-2 214 BibliographY Anouilh, J. (1946) Antigone, trans. Lewis Galantière (New York: Random House). Arendt, H. (1943) ‘We Refugees’, The Menorah Journal, 31 (1) 69–77. -

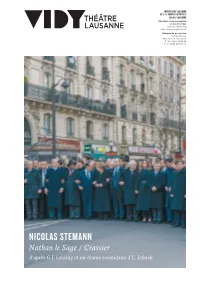

NICOLAS STEMANN Nathan Le Sage / Crassier D’Après G.E Lessing Et Un Drame Secondaire D’E

THÉÂTRE VIDY-LAUSANNE AV. E.-H. JAQUES-DALCROZE 5 CH-1007 LAUSANNE Directrice de la production et des tournées Caroline Barneaud Mail: [email protected] Chargée de production Sophie Mercier Mail: [email protected] T +41 (0)21 619 45 83 P+41 (0)78 807 63 45 NICOLAS STEMANN Nathan le Sage / Crassier d’après G.E Lessing et un drame secondaire d’E. Jelinek NICOLAS STEMANN NATHAN LE SAGE 2 NATHAN LE SAGE Création à Vidy Mise en scène : Nicolas Stemann Traduction et dramaturgie : Mathieu Bertholet Scénographie : Katrin Nottrodt Musique : Waël Koudaih (Rayess Bek) Costumes : Marysol del Castillo Vidéo : Claudia Lehmann Assistanat mise en scène : Nora Bussenius Stagiaire assistanat mise en scène : Mathias Brossard Stagiaire assistanat costumes : Giulia Rossini Construction du décor : Ateliers du Théâtre de Vidy Avec : Lorry Hardel Lara Katthabi Mounir Margoum Serge Martin Elios Noël Véronique Nordey Laurent Papot Lamya Regragui et les musiciens : Waël Koudaih (Rayess Bek) Yann Pittard Production : Théâtre de Vidy Coproduction : MC93-Maison de la Culture de la Seine St-Denis, Bobigny Théâtre National de Strasbourg Théâtre National de Bretagne Bonlieu Scène nationale Annecy et La Bâtie-Festival de Genève dans le cadre du programme INTERREG France-Suisse 2014-2020 Avec le soutien de: Fonds d’Insertion pour Jeunes Artistes Dramatiques, D.R.A.C. et Région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur Pro Helvetia - Fondation suisse pour la culture L’Arche est l’agent théâtral d’Elfriede Jelinek Création le 14 septembre 2016 au Théâtre de Vidy Durée estimée : 2h NICOLAS STEMANN NATHAN LE SAGE 3 PRÉSENTATION En 2009 au Thalia Theater de Hambourg, Nicolas Stemann mettait en scène Nathan le Sage, le célèbre chef d’oeuvre de Lessing, complété par un « drame secondaire » commandé à Elfriede Jelinek.