Resolutins of the Working Conference. Working Groups Discussed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renaming of Residences

RENAMING OF RESIDENCES Auckland Park Campus Original Meaning Date of New Name proposed in 2015 Type of Male/Female/Mixed Name Inception Residence Residence Amper Daar Amper Daar is an Afrikaans word 1975 Magnolia – (French). Named after the French Residence Female meaning "Almost there". The name botanist Pierre Magnol. It symbolises divine beauty, has links with the golf course on perseverance, long life and strength. which the University was built. Alomdraai Alomdraai is Afrikaans for full turn. 1977 Akani – (Tsonga). Meaning “To build”. Day House Female Benjemijn Benjemijn is of Dutch origin 1980 Impumelelo – (Nguni). Meaning “'success by working Residence Female meaning “Is jy myne?” or “Are you together”. mine?” Kruinsig Loosely translated means the view 1975 Mošate Heights – (Sepedi). Meaning of Mošate Residence Female from the top. “royal kraal or palace”. Lebone Lebone is a Sotho word for “Dawn 2000 Lebone – (Sotho). Meaning “light”. (Retention of Residence Female of light/Light of achievement”. name) Skoonveld An Afrikaans word which means 1983 Karibu-Jamii – (Kiswahili). Meaning “welcome Residence Female “fairway”. The name recalls the family”. previous golf course and a leisurely past as the University was built on the old Johannesburg Country Club. Afslaan Afslaan translates into “Tee off”. 1968 Afslaan – (Afrikaans). Meaning “tee off” in golf. Residence Male The name recalls the previous golf (Retention of name). course and a leisurely past as the University was built on the old Johannesburg Country Club. Bastion The word “Bastion” refers to the 1980 Maqhawe – (Ndebele/Zulu/Xhosa). Meaning Residence Male strongest cornerstone of a castle. “heroes”. Dromedaris Has a link to “South Africa’s 1975 Cornerstone – (English). -

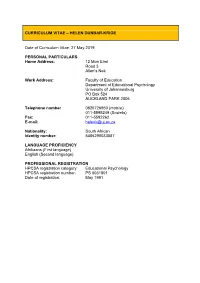

HELEN DUNBAR-KRIGE Date of Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE – HELEN DUNBAR-KRIGE Date of Curriculum Vitae: 27 May 2019 PERSONAL PARTICULARS Home Address: 12 Mon Elmi Road 3 Allen’s Nek Work Address: Faculty of Education Department of Educational Psychology University of Johannesburg PO Box 524 AUCKLAND PARK 2006 Telephone number 0825726950 (mobile) 011-5595249 (Soweto) Fax: 011-5592262 E-mail: [email protected] NationalIty: South African Identity number: 5406290033087 LANGUAGE PROFICIENCY Afrikaans (First language) English (Second language) PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION HPCSA registration category: Educational Psychology HPCSA registration number: PS 0031801 Date of registration: May 1991 1. ACADEMIC PROFILE 2007 D Ed Educational Psychology University of Johannesburg Title of Thesis: The facilitation of reflection in initial teacher education 1991 M Ed Educational Psychology (cum laude), Rand Afrikaans University 1989 B Ed (Hons) Educational Psychology, Rand Afrikaans University 1978 HED Rand Afrikaans University 1976 BA Social Science, Rand Afrikaans University Majors: History Biblical Studies Psychology 2. CAREER SUMMARY August 2000 to present: Lecturer / Senior lecturer in educational psychology May 1997 to July 2000: Part time lecturer in educational psychology, guidance and counseling August 1996 to August 2000: Educational psychologist in private practice January 1991 to July 1996: School psychologist: Forest Town School for cerebral palsy and learning difficulties Part time private practice January to December 1990 Intern educational psychologist at the Institute for Child and -

Auction Catalogue

APPRECIATING PROPERTY ARCHITECTURE VIRTUAL ONLINE AUCTION EVENT ~ 2 DECEMBER 2020 @ 12:00 ~ Auctioneer: Joff van Reenen DOWNLOAD OUR APP BID ANYWHERE! THIS DYNAMIC APP ALLOWS YOU TO: • Stay Informed • View Properties • Push Notifications The High Street Auction Company APP REGISTRATION & BIDDING PROCESS SIGN UP & APP REGISTRATION PROCESS Ÿ Once you have downloaded the app, open it and click on “VIEW AUCTION” to view our current auction properties. Ÿ In order to bid on a property you will need to SIGN IN. Either click on the drop-down menu top right or click on “REGISTER TO BID”. Ÿ If this is the 1st time using the app please click on “SIGN UP HERE”, otherwise type in your email address and password and sign in. Ÿ Fill in all fields (Please ensure your password is a min. of 8 characters), and tick “Receive bidding notifications via email” & click “CONTINUE”. Ÿ Agree to the Terms of use and click “SIGN UP”. Ÿ Once you have signed up you need to register to bid on a specific auction. Please click on “REGISTER TO BID”. Please note you need to register for each auction to would like to participate in. Ÿ Please complete all the fields and click “CONTINUE”. The High Street Auction Company Ÿ Agree to the Auction Terms & Conditions and click “REGISTER”. Ÿ You will receive a successfully registered message, where you will be approved once all your documents and we have received your proof of payment of your registration fee. ONLINE BIDDING PROCESS Ÿ Once you have been approved by The High Street Auction Co, you will be notified that you can begin to bid. -

Country Club, Johannesburg, South Africa

Country Club, Johannesburg, South Africa About The Club Parking The Country Club Johannesburg is one club with two Yes parking available at both Woodmead and venues. Our properties are a 20 minute drive apart. Auckland park. Located in the heart of Johannesburg, Auckland Park is the original home of CCJ and includes spectacular venues Dining Facilities for weddings and other celebrations. The widespread The Country Club Johannesburg’s restaurants offer a wealth of choices whether it be a formal dining experience, grounds are host to a number of outstanding sporting a casual family lunch or anything in between. The Club has facilities and include accommodation. a variety of options. The property is situated just north of Woodmead At Auckland Park, order pub meals in The Club Room Johannesburg and spreads across 236 hectares and is while playing a round of snooker or watching sport on the home to two superb golf courses: Woodmead and big screen TV. The Gallery Restaurant is open all day for Rocklands, ranked 9 and 59 in South Africa respectively. meals, while The Rainbow Room offers delicious buffet It is recognised among the most prestigious venues for lunches on Fridays. corporate golf days. Contact Information The outstanding views at Woodmead complement its Napier Road restaurants’ excellent food. The Grill Room offers a sushi Auckland Park bar and à la carte menu, Tuesday – Saturday lunch and Johannesburg 2006 dinner as well as Sunday lunch while The Member's Bar South Africa serves wholesome meals until late evening. The Club Tel: (0027) 11 710-6400 Terrace boasts a panoramic view of Johannesburg and is a favourite for after-work sundowners and snacks. -

Region B Contact & Information Directory

REGION B CONTACT & INFORMATION DIRECTORY UPDATED JANUARY 2016 REGION B CONTACT & INFORMATION DIRECTORY: JANUARY 2016 INDEX NAME PAGE Emergency Numbers …………………………………………………………………… 1 Head Office Staff A – Z …………………………………………………………………… 1 – 6 Ward Councillors …………………………………………………………….…….. 6 -7 Ward Governance Administrators …………………………………………………………………… 8 PR Councillors …………………………………………………………………… 8 Group Citizen Relationship & Urban Management (CRUM): Head Office …………………………… 8 - 9 Regional Directors A – G …………………………………………………………... 9 - 10 Citizen Relationship & Urban Management Management Support …………………………………………………… 10 Area Based Management …………………………………………………… 11 Citizen Relationship Management …………………………………………………... 11 Integrated Service Delivery …………………………………………………... 12 Planning, Profiling & Data Management …..……………………………………… 12 Health Community Health Clinics …………………………………………………… 13 – 14 Environmental Health …………………………………………………… 15 – 18 Housing …………………………………………………………………… 19 Libraries …………………………………………………………………… 20-21 Social Development TDC (Transformation & Development Centre) ………………………………………… 22 Techno Centre …………………………………………………………………… 23 Sport and Recreation Recreation …………………………………………………………………… 23 Recreation Centres …………………………………………………………………… 24 NAME PAGE Sport …………………………………………………………………… 25 Sports Clubs & Stadiums …………………………………………………………………… 25 – 26 Aquatics …………………………………………………………………… 26 Swimming Pools …………………………………………………………………… 26 – 27 Group Finance Revenue Shared Services Centre ………………………………………………….. 27 Development Planning Building Control -

Inner City Transformation Road Map Update on Inner City Implementation 2016 - 18 Department of Economic Development

Inner City Transformation Road Map Update on Inner City Implementation 2016 - 18 Department of Economic Development 06 February 2017 Introduction Johannesburg Inner City 2 • Accelerated degeneration from the early 1990's • However, the over R14 billion investment has transformed the physical and economic features of the Inner City • Some notable pockets of excellence, including, inter alia: • Newtown • Maboneng • Marshalltown • Fox Street / Ghandi Square • Headquarters of Standard Bank, ABSA (Barclays), First National Bank, Transnet, Anglo American, Billiton, The Star newspaper, the Chamber of Mines, and Credit Suisse • Investment creates construction-related employment opportunities, over 120 000 in the last 10 years • However chunks of derelict and dilapidated buildings remain, which harbour criminality and perpetuate urban decay Introduction Johannesburg Inner City – Pockets of Excellence 3 Turbine Hall Ghandi Square Hatton Mathomo Mall Arts on Main FNB Bank City Introduction Johannesburg Inner City – Strategic Direction 4 • The political and administrative management teams of the city decided on a 10-Point Plan in 2016: 1. A recognition of political arrangement/coalition imposed by the electorate 2. A responsive and pro-poor CoJ government 3. Achieving a 5% economic growth rate 4. Creating a professional public service 5. Ensuring corruption is public enemy number 1 6. Revive the Johannesburg inner city 7. Complete the official housing waiting list 8. Produce a report on the number of completed houses built by the city and the province -

Call for Papers: 'Good Governance, Participatory

CALL FOR PAPERS: ‘GOOD GOVERNANCE, PARTICIPATORY DEMOCRACY, AND SOCIAL JUSTICE: CIVIL SOCIETY AS AN AGENT OF CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN AFRICA’ CONFERENCE 31 August-1 September 2021 In Africa, civil society has played, and continues to play, a critical role in providing space for both change and mass innovation throughout the continent. In recognition of this, the Faculty of Humanities at the University Johannesburg (UJ) will be hosting the ‘Good governance, participatory democracy, and social justice: Civil society as an agent of change and innovation in Africa’ conference. The conference is due to take place at the Capital Hotel, Melrose, in Johannesburg, South Africa, from 31 August to 1 September 2021 and will be hybrid in nature. This conference will bring together, both face-to-face and virtually, representatives and scholars of civil society from across Africa to review and assess the constructive roles that civil society has played and continues to play on the continent in addressing a range of political and socio-economic challenges. To this end, the conference organising committee welcomes abstracts from organisers in civil society and scholars that address the theme of African civil society from one or more of the following areas: • Good governance • The quality of democracy • Youth, youth empowerment and youth as agents of change • Human rights promotion • Environmental issues and the Sustainable Development Goals • Technology • Gender • Entrepreneurship and business development • COVID-19 and other health matters Abstracts should be typed in Arial size 12 font and be no longer than 300 words and should include: • The title of the paper • A tentative outline of the paper • The names and affiliations of all authors • The email address of the corresponding author • Five keywords Abstracts can be submitted via email to Mr Sven Botha at [email protected] by no later than the 1st of April 2021. -

Our Areas of Finance Our Branches

OUR BRANCHES OUR AREAS OF FINANCE GAUTENG GAUTENG Johannesburg Pretoria JOHANNESBURG • Hillbrow • Rosettenville 12th Floor, Libridge Building 8th Floor, Olivetti House • Auckland Park • Jeppestown • Rouxville 25 Ameshoff street 100 Pretorius Street • Bellevue • Johannesburg CBD • Selby Braamfontein Cnr Pretorius & Schubart Str • Bellevue East • Joubert Park • Springs CBD Johannesburg, 2001 Pretoria, 0117 • Benoni • Judiths Paarl • Troyeville +27 (10) 595 9000 +27 (10) 595 9000 • Berea • Kempton Park CBD • Turf Club WELCOME • Bertrams • Kenilworth • Turffontein • Bezuidenhout KWAZULU NATAL • Kensington • Westdene Valley • Krugersdorp • Witpoortjie 27th Floor, Embassy Building • Boksburg North • La Rochelle • Yeoville TO TUHF 199 Anton Lembede Street • Braamfontein Durban, 4001 • Langbaagte • Brakpan +27 (31) 306 5036 • Lorentzville PRETORIA • Brixton • Marshall Town • Arcadia • City and Suburban • Melville • Capital Park CBD EASTERN CAPE • Doornfontein • New Doornfontein • Gezina CBD 2nd Floor, BCX Building • Fairview • Newtown • Hatfield 106 Park Drive • Florida • North Doornfontein • Pretoria CBD St. George’s Park • Forest Hill • Orange Grove • Pretoria North CBD Port Elizabeth, 6000 • Germiston • Primrose • Pretoria West +27 (41) 582 1450 • Highlands • Randburg CBD • Silverton CBD • Highlands North • Roodepoort • Sunnyside WESTERN CAPE KWAZULU NATAL 5th Floor South Block, Upper East Side 31 Brickfield Road DURBAN • Montclair • Wentworth Woodstock, • Albert Park • Overport Cape Town, 7925 • Bluff • Pinetown Central PIETERMARITZBURG +27 -

APPENDIX a Historical Overview of the Corridors of Freedom

APPENDIX A_Historical overview of the Corridors of Freedom By Clive Chipkin Geology & Topography GEOLOGY and the 19-century World Market determined the locality of Johannesburg. TOPOGRAPHY contributes significantly to the sense of place, the genius loci, in a region of low hills and linear ridges. Gatsrand, 30 Km to the South; Suikerbosrand, 30 Km to the South East; the Klipriviersberg immediately to the South. In the foreground are the parallel East- West scarps and residue hills of the area magically named the Witwatersrand, looking northwards across a panorama of rolling country and gently sloping valleys to the Magaliesberg horizon – all part of the multiple Johannesburg immersion. Fig. 168 Section of topographical map of Johannesburg. (Source: Office of Surveyor General, Cape Town, surveyed in 1939) The great plains of the continental plateau enters the town-lands: the Houghton- Saxonwold plain north of the ridges and Doornfontein to Turffontein plain occupying the space between the Braamfontein high ground and the Klipriviersberg. The spaciousness – a word used by the visiting geographer JHG Lebon (1952:An Introduction to Human Geography) – of the landscape means that Johannesburg, unlike Durban and Cape Town can expand in almost any direction but after a century plus decades of urban growth, it is our delectable ridges that remain repositories of ancientness. The north facing Parktown ridge with its extension on the Westcliff promontory and its continuation as the Houghton and Orange Grove escarpment to the east 244 Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] form a decisive topographical feature defining the major portion of the Northern Suburbs as well and the ancient routes of the wagon roads to the north. -

Implementation of Practical Marketing Strategies for Soweto Schools

13S36 0 S- IMPLEMENTATION OF PRACTICAL MARKETING STRATEGIES FOR SOWETO SCHOOLS by MARIA SEWELA MABUSELA S e7,- 0 BAED (VISTA); BED (VISTA) tAn A-6u Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree MAGISTER EDUCATIONIS in the DEPARTMENT OF POSTGRADUATE EDUCATION at VISTA UNIVERSITY SUPERVISOR: DR B.V. NDUNA JOINT SUPERVISOR: PROF. J.R. DEBEILA UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG LIBRARY AND INFORMATION CENTRE AUGUST 2002 2006 -01- 0 5 JOHANNESBURG SOWETO CAMPUS UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Soweto Campus Library PO BOX 524 AUCKLAND PARK 2006 Tel: (011) 933-5667 This item must be returned on or before the last date stamped. A renewal for a furtherperiod may be granted provided the book is not in demand. Fines are charged on overdue items: %iv 2006 vis 0 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the people whose names appear: I would like to express my thanks to my late mother Johannah Mabusela as well as my late brother Phillip and sister Gloria for the groundwork they laid concerning my education. My dearest gratitude also goes to my grandmother Sannie Mabusela and my aunt Elsie Mabusela who nurtured me after my mother's demise. Mostly unto the Lord, the God of Africa through Him all is feasible. Dr B.V. Nduna, Professor J.R. Debeila and Mr Z. Khoza for guidance and advice and concern of research standards. Mrs D.M. Mhlongo for the typing of the manuscript. DECLARATION "I declare that: IMPLEMENTATION OF PRACTICAL MARKETING STRATEGIES FOR TOWNSHIP SCHOOLS is my work, that all the sources used or quoted have been linked and acknowledged by means of complete references, and that this dissertation was not previously submitted by me for a degree at another university". -

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors by Region, Suburbs and Political Party

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS BY REGION, SUBURBS AND POLITICAL PARTY No. Councillor Name/Surname & Par Region: Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Cotact Details: ty: No: 1. Cllr. Msingathi Mazibukwana ANC G 1 Streford 5,6,7,8 and 9 Phase 1, Bongani Dlamini 078 248 0981 2 and 3 082 553 7672 011 850 1008 011 850 1097 [email protected] 2. Cllr. Dimakatso Jeanette Ramafikeng ANC G 2 Lakeside 1,2,3 and 5 Mzwanele Dloboyi 074 574 4774 Orange Farm Ext.1 part of 011 850 1071 011 850 116 083 406 9643 3. Cllr. Lucky Mbuso ANC G 3 Orange Farm Proper Ext 4, 6 Bongani Dlamini 082 550 4965 and 7 082 553 7672 011 850 1073 011 850 1097 4. Cllr. Simon Mlekeleli Motha ANC G 4 Orange Farm Ext 2,8 & 9 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 550 4965 Drieziek 1 011 850 1071 011 850 1073 Drieziek Part 4 083 406 9643 [email protected] 5. Cllr. Penny Martha Mphole ANC G 5 Dreziek 1,2,3,5 and 6 Mzwanele Dloboyi 082 834 5352 Poortjie 011 850 1071 011 850 1068 Streford Ext 7 part 083 406 9643 [email protected] Stretford Ext 8 part Kapok Drieziek Proper 6. Shirley Nepfumbada ANC G 6 Kanama park (weilers farm) Bongani Dlamini 076 553 9543 Finetown block 1,2,3 and 5 082 553 7672 010 230 0068 Thulamntwana 011 850 1097 Mountain view 7. Danny Netnow DA G 7 Ennerdale 1,3,6,10,11,12,13 Mzwanele Dloboyi 011 211-0670 and 14 011 850 1071 078 665 5186 Mid – Ennerdale 083 406 9643 [email protected] Finetown Block 4 and 5 (part) Finetown East ( part) Finetown North Meriting 8. -

Open Branches Gauteng

OPEN BRANCHES GAUTENG TOWN SUBURB STREET BEDFORDVIEW BEDFORD GARDENS CORNER BRADFORD AND SMITH STREET BEDFORDVIEW OOSPOORT 43 BRADFORD ROAD BENONI BENONI CORNER ELSTON AVENUE AND TOM JONES BOKSBURG JANSEN PARK EXT 10 CORNER K90 AND NORTH RAND ROAD BRONKHORSTSPRUIT BRONKHORSTSPRUIT KRUGER STREET CARLETONVILLE CARLETONVILLE CORNER ANNAN ROAD AND GOLD STREET CENTURION CENTURION CORNER HENDRIK VERWOERD AND SOUTH STREET JOHANNESBURG MARSHALLS TOWN SMAL STREET JOHANNESBURG MAYFAIR 51 HANOVER STREET JOHANNESBURG BRAAMFONTEIN 76 JORRISEN STREET JOHANNESBURG KILLARNEY 60 RIVIERA ROAD JOHANNESBURG ROSEBANK 50 BATH AVENUE JOHANNESBURG JOHANNESBURG 175 JEPPE STREET JOHANNESBURG SOUTHDALE CORNER ALAMEIN STREET AND LANSBSBOURG JOHANNESBURG AUCKLAND PARK CORNER MAIN ROAD AND THIRD AVENUE JOHANNESBURG GLENEAGLES EXT 2 CORNER LETABA AND ORPEN STREETS JOHANNESBURG SOUTHGATE CORNER COLUMBINE AND RIFLE STREETS JOHANNESBURG SELBY 5 SIMMONDS STREET JOHANNESBURG RISPARK AH SWARTKOPPIES ROAD AND KLIPRIVIER DRIVE KEMPTON PARK ESTHER PARK EXT 9 CORNER KELVIN STREET AND SWART ROAD KEMPTON PARK GREENSTONE PARK PROPER CORNER MODDERFONTEIN ROAD AND VAN RIEBEECK AVENUE KRUGERSDORP PRETORIUS PARK CORNER PAARDEKRAAL AND DR.VILJOEN STREET LENASIA AND ELDORADO PARK LENASIA EXT 8 CORNER K53 AND NIRVANA ROAD MABOPANE MABOPANE EW STAND 425 UNIT E, M17 MIDRAND HALFWAY HOUSE OLD PRETORIA ROAD MIDRAND MIDRIDGE PARK EXT 14 CORNER LEVER ROAD AND NEW ROAD MIDRAND VORNA VALLEY OUTLYING CNR ALLANDALE RD & MAXWELL DR NIGEL NIGEL EXT 1 CORNER 1ST AVENUE AND CHURCH STREET PRETORIA SUNNYSIDE